A UCMP special exhibit

The Art of Sculptor William Gordon Huff

Part I: The Early Years, 1903 to 1939

by David K. Smith

Who is this guy?

William Gordon Huff was a great California sculptor but few people have ever heard of him. This is regrettable but understandable since (1) he took few commissions after the outbreak of World War II (when he took a full-time job); (2) most of his work was of a public and sometimes temporary nature; and (3) little of his work is exhibited in art galleries or any major museum. I knew nothing about Huff before coming to work at the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) in 1996.

What I did learn about Huff came from the UCMP website, one of the first two museums represented on the World Wide Web, debuting in 1993. Paleontology grad student P. David Polly (now Professor of Geological Sciences at Indiana University) had posted a few pages about Huff's work that same year (the year Huff died) and photos of some of Huff's prehistoric animal sculptures were featured on the museum's earliest home pages. The photos used on these pages came from two scrapbooks in the UCMP Archives that Huff must have given to the museum. The scrapbooks contained only photos—no captions, no text. In 2011 I began to wonder about the Huff-UCMP connection and its origins for I'd come across nothing new to shed light on the man or the relationship during the 15 years I'd been with UCMP. Who was this guy?!

In 2011 there wasn't much to be found online about Huff. Even today, an internet search will turn up little. Our website's main focus has been on Huff's contributions to the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940. Other sites tend to emphasize Huff’s Chief Solano project and may provide images of some of his historical plaques, but that’s about it. I wanted to know more.

I began asking around and got a couple important leads from Professor Emeritus Bill Clemens and Assistant Director for Collections and Research Mark Goodwin. Bill told me that he'd attended Berkeley High School with Huff's daughter Antonia; he had contact information for her so he'd give her a call and invite her to the museum. Mark recalled that he'd been contacted some months previous by Tim, one of Huff's two sons, and he shared Tim's email address with me. Antonia did come to the museum and I successfully connected with Tim. Both were thrilled to find that I was interested in their father and his art, and thanks to them, this not-quite-a-biography was made possible.

How this is organized

This first page covers Huff's life chronologically to just before the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940 (GGIE). The GGIE is covered on page 2. Page 3 focuses on Huff's relationship with the Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus and his historical plaques. Page 4 concerns some 1939-1941 projects and Huff's art connected with the Alameda Naval Air Station. Page 5 covers a wide range of projects that Huff was involved with from the 1940s through the 1970s. On Page 6 we examine Huff's personal art pursuits and an assortment of artwork from the Huff Family Archives. Page 7 is a chronological list of Huff-related events (projects, plaque dedications, etc.).

♦ Part I: The Early Years, 1903 to 1939

♦ Part II: The Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940

♦ Part III: E Clampus Vitus and Historical Plaques

♦ Part IV: Post-GGIE and the Alameda Naval Air Station

♦ Part V: Projects Through the 1970s

♦ Part VI: Personal Art and Miscellaneous Works

♦ A Huff Chronology

Rather than add to the length of each page by including footnotes, each has a separate, associated page called "Sources and Supplemental Information" containing references and somewhat peripheral, but to my way of thinking, interesting tidbits. For easy reference, I suggest keeping the Sources page open while reading the main text: open the Sources page for Part I in a new tab/window.

Clicking on most of the images in this feature will bring up larger and often more complete versions; these images are indicated within the captions (look for the italicized text). To keep things simple, all the enlarged images as well as all links within the pages (with the exception of the Sources pages) will open in the same browser window. To return to where you were previously, click your browser's Back arrow.

Acknowledgements

The backbone of this feature is an informal autobiography—photocopied handwritten sheets interspersed with yearbook images, newspaper clippings and photos—that Huff produced for his children. As he himself put it, "I have put together, chronologically, enough information in xerox form to let my descendants know what one of their progenitors did with his time while here on Earth."1 Other major sources of information include (1) an extensive collection of correspondence, photos, newspaper clippings, artwork and other memorabilia (the Huff Family Archives) shared with me by Huff's eldest son Tim; (2) artwork, negatives and other materials shared by Huff's daughter Antonia Huff Rodrigues; (3) artwork, photographs and correspondence in the UCMP Archives; and (4) interviews with Huff held during the last few years of his life, conducted by Tim Huff and close friends. Several other people contributed valuable information such as UCMP's Mark Goodwin; Callie Stewart, Bennington Museum; Deke Sonnichsen, historian, and Steve "Iggy" Myers, Ex-Noble Grand Humbug, both of the Yerba Buena No. 1 Chapter of E Clampus Vitus; Jack "Jackrabbit" Furlow of the Mountain Charlie 1850 Chapter of E Clampus Vitus; Terri Sheridan, librarian at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History; Gray Brechin, Department of Geography, UC Berkeley; Cricket Kanouff, Jerry Bowen and Brian Irwin of the Peña Adobe Historical Society and/or Vacaville Heritage Council; Richard Dyer of sfsdhistory.com; Kathleen Duxbury, Civilian Conservation Corps researcher; Ruth Lang, Fresno Historical Society; Matthew Smith, Petrified Forest National Park; and especially Mark Humpal, Portland, Oregon, art dealer and historian who provided a wealth of images and information regarding Huff's friend and frequent collaborator, Ray Strong, as well as correspondence from the Ray Strong Family Papers.

Abbreviations: Tim Huff and the Huff Family Archives, Laytonville, CA HFA; Antonia Huff Rodrigues, Santa Rosa, CA (all photographed by Dave Strauss) AHR; California School of Fine Arts CSFA; University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) Archives, Berkeley, CA UA; Ray Strong Family Papers, Upper Lake, CA RSFP

The early years

Thomas Edmond Huff (1857-1924), William's father, was born and raised in Illinois and for a couple of years in the late 1870s he helped drive cattle along the Chisholm Trail from Texas to the Chicago stockyards. He moved to Fresno, California, in 1883 when he was 26 and made a living selling, buying and trading cattle and horses for several years; at one point he owned two livery stables in town (possibly not concurrently), one at the corner of Mono and J Streets (J is now called Fulton) and another at Fresno and I Streets (I is now Broadway).1 He married Celia Alida Gordon (1863-1918) of Bellflower, California, in 1888.2 The couple spent 30 years in Fresno raising a family of seven children and lived at a number of different addresses during that time.3

William was born on February 3, 1903. He attended the Washington Grammar School in Fresno where, at the age of eight or nine, he acquired his love of drawing.4 While a freshman at Fresno High School he developed self-confidence and leadership abilities as a member of the Public Speaking Club.5

By 1913, the automobile was gaining in popularity and Thomas's business began to suffer as a result; so he sold his stables and tried his hand at real estate.6 In 1918, following William's freshman year, the household was hit with a major tragedy when Celia Huff died of influenza. Later that year Thomas moved the family to Oakland, taking up residence at 881 59th Street.7

Click on the image to see an enlargement. Portion of a 1901 map of downtown Fresno indicating the locations of Thomas Edmond Huff's two stables, Huff Stables on the left and Mono Stables on the right. Adapted from a 1901 Fresno map by L.W. Klein, accessed Nov 24, 2017.

William was enrolled at Oakland Technical High School. There he joined the Glee Club—he had a fine baritone and sang many solos. He served as vice president of the Honor Society and also did a bit of acting.8 Huff was an active member of the R.O.T.C. at Oakland Tech and rose to the rank of major, commanding the school's battalion of three to four hundred cadets.9

Top left: Washington Grammar School, the school Huff attended in Fresno. Photo from Bruce, W.G., W.C. Bruce, and S. Cocroft. 1906. The American School Board Journal, volumes 32-33. National School Boards Association. Top right: Fresno High School. The photo dates from 1918, the year the Huff family moved to Oakland. The photo is in the public domain. Middle left: Huff's photo from The Owl, the Fresno High School yearbook, 1918. Although he was a freshman, he was a member of the Public Speaking Club that year. Middle center: The grand facade of Oakland Technical High School in the early 1920s. The building was only four years old when Huff transferred there. Photo by Vena Wright, courtesy of the Oakland Unified School District, Visual Education Department. Middle right: Huff in a group photo of the Oakland Tech Glee Club, 1920. HFA. Click on the image to see the entire glee club. Bottom: Major Huff (center) with members of his ROTC battalion, 1921. HFA.

Huff developed an interest in history while attending Oakland Tech. As a sophomore he enrolled in his first art class, but his "favorite academic classes were English and History—took it all—ancient, medieval, modern and U.S."10

Upon graduating in 1921, Huff chose to pursue an art career, however, he was able to blend his art and history interests on numerous occasions later in life. Huff began his art training at what was then the California Guild of Arts and Crafts (now Oakland's California College of the Arts) in Berkeley where he met noted sculptor Beniamino (Benny) Bufano.11 Huff spent a year at the Berkeley school but then Bufano took a job as an instructor at the California School of Fine Arts (CSFA) in San Francisco (now the San Francisco Art Institute) and convinced Huff to follow him there. Bufano became one of Huff's mentors, as did another instructor, sculptor Edgar Walter.12 Walter said of Huff, "some day San Francisco will be proud to own him as a son"13 and it was Walter's influence that led to Huff's first major commission at the age of 19.

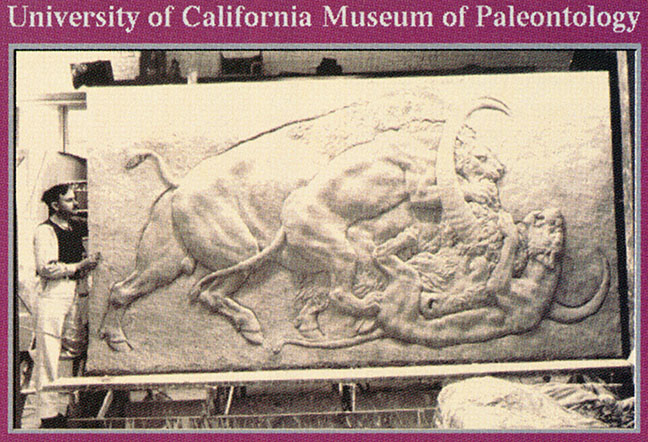

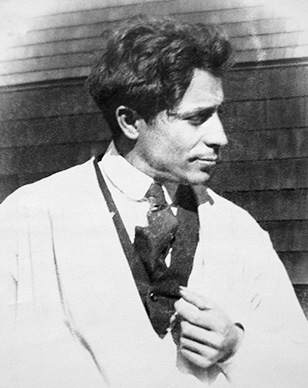

Top left: The California Guild of Arts and Crafts as it looked in Huff's day. The building was located just west of the UC Berkeley campus at 2119 Allston Way, where the Magnus Museum is today. From the California College of the Arts Vault. Top right: Huff's sculpture class at the California Guild of Arts and Crafts during the 1921-1922 academic year. Huff is indicated by the circled "X." Bufano is at the far right. Click the image to see an enlargement. HFA. Bottom left: Benny Bufano in spring 1921. Click the image to see an enlargement. HFA. Bottom right: A portion of Edgar Walter's 1934 pediment sculpture for the Andrew W. Mellon Auditorium in Washington, DC. Compare Walter's figures with the monumental figures that Huff sculpted for the 1939-1940 Golden Gate International Exposition (see page 2). Could Walter have influenced Huff's style? Photo © Bruce Guthrie.

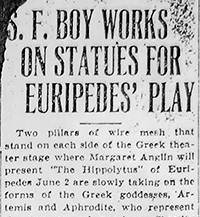

This first commission was on the UC Berkeley campus. Completed in 1923, Huff built standing figures of the Greek goddesses Artemis and Aphrodite—each more than 15 feet tall—for a stage production at the Greek Theater. The figures were constructed by applying plaster to a framework of wood and wire mesh.14

Top: The William Randolph Hearst Greek Theater on the UC Berkeley campus as it looked just before Margaret Anglin's production of Hippolytus, June 2, 1923. Click on the image to see closeups of Huff's statues of Artemis and Aphrodite. HFA. Bottom: Two newspaper articles (source newspapers unknown) advertising the upcoming production. Click on the images to see the complete articles. HFA.

To earn extra money while in school and perhaps to gain some experience, Huff took a job with the Artstone Distributing Company, a business that made concrete garden furniture. Huff only worked there for six months, but by the end of that period, the company, located at 2-4 Valencia Street in San Francisco, had put him in charge of "all modeling and designing."15

It didn't take long for Huff's talents to be recognized at the CSFA. In the fall of 1922, Huff entered a sculpted piece in the San Francisco Art Association's annual exhibition. His work, entitled Study, won an honorable mention in the event held at the Palace of Fine Arts. The following March, he entered a piece cast in plaster called Figure Study in the CSFA's annual competition and was one of ten students to win a scholarship to the Art Students' League of New York.16 Later in 1923, Huff's sculpted head of a young girl won a first place in a competition at the School of Fine Arts.17

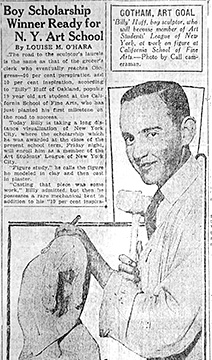

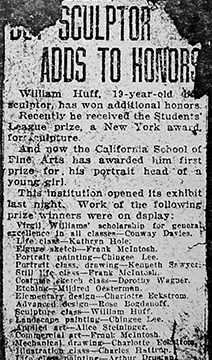

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Top left: Huff (far right) with his sculpture class at the CSFA during the 1922-1923 academic year. HFA. Top right: Huff (seated) shared a San Francisco studio with three of his classmates while at CSFA. HFA. Bottom left: Newspaper article from the May 15, 1923, issue of the San Francisco Call and Bulletin concerning Huff's scholarship to the Art Students' League of New York. HFA. Bottom center: Huff's "Figure Study." HFA. Bottom right: A newspaper article (source newspaper unknown but post-May 1923) listing prize winners of an art competition at the CSFA. HFA.

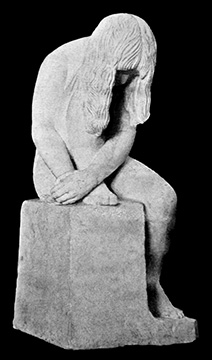

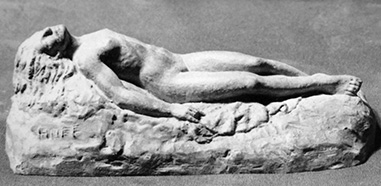

Click on either image to see a larger version. Two nude sculptures that probably date from Huff's CSFA days. HFA.

To New York

Armed with letters of recommendation and a letter of introduction from Benny Bufano to his brother Remo, Huff headed to New York City around October 1923.1 Three of his fellow art student friends, Raymond Jones (who was also a childhood friend from Fresno), Conway Davies, and Paul Ogden, joined him there. The four young men shared a studio apartment in the Lincoln Arcade Building on Broadway between West 65th and 66th Streets.2 This conveniently put Huff just a few blocks from the Art Students League at 215 West 57th Street.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: The Broadway facade of the Lincoln Arcade building. This photo probably was taken about ten years before Huff and his friends moved in. From cinema treasures.org/photos/170834, uploaded by Granola. Center: Paul Ogden, one of Huff's art student roommates, in New York City. HFA. Right: The New York Art Students' League has not moved since Huff's day, although its building was getting an upgrade when this photo was taken in 2016. Photo by David Smith.

Huff and his friends each pursued their own dreams in New York, but they did manage to find common employment through Remo Bufano's connections.

Remo Bufano

Remo, the second person Huff went to see upon arriving in New York City, was an artist in his own right and an up-and-coming talent in the world of marionette puppetry.1 Bufano's workshop was located at 49 Vandam Street in Greenwich Village. Living uptown, Huff must have taken public transportation to go to and from the studio. He wrote "I 'hit it off' with Remo whose studio was a haven of warmth in my early New York days. In my off hours I worked with him—and a wonderful person he was—modeling puppets and learning the technique of puppet construction; marionette stage construction and the whole art of the marionette theatre. I also acted as a puppeteer."2

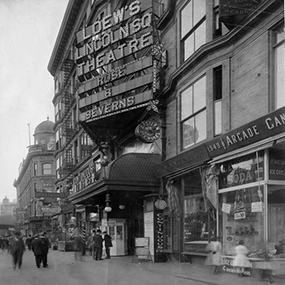

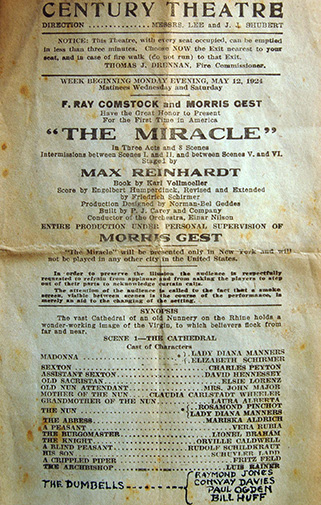

Remo, who had many connections in the New York theater world, was engaged to create special puppets for Max Reinhardt's The Miracle3 which opened at the Century Theater on January 12, 1924. Through Remo, Huff and his friends were able to get parts as extras in the production. The show ran for ten months so the friends were receiving steady pay almost immediately after having arrived in the city.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: Remo Bufano with one of his marionettes in 1932. From the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; © The Estate of Prentiss Taylor. Right: The cast and credits of Max Reinhardt's production of The Miracle. Note that at the bottom Huff wrote in the roles that he and his buddies played. HFA.

Arthur Lee

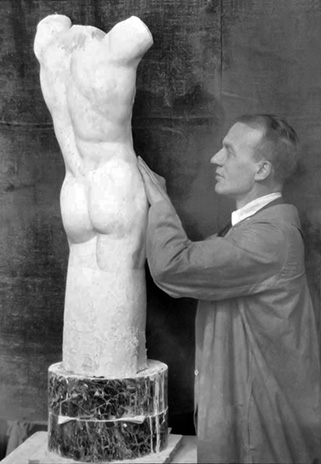

Lee, a sculptor best known for his classical nude figures, was the first person Huff looked up after arriving in New York City. Lee Randolph, Director of the California School of Fine Arts, had written to Lee on Huff's behalf in early October of 1923 saying "I am sure you will find him [Huff] a boy very well worth while, and we will greatly appreciate any help you may be able to give him in the prosecution of his work in New York."1 Lee had a studio in Greenwich Village at 9 MacDougal Alley, again, a long way from Huff's apartment, but not that far from Bufano's studio. When Huff arrived in New York City, Lee was probably making a modest living off sculptural commissions and private lessons. He hired Huff on to assist him in his studio, particularly with casting, which was one of Huff's specialties. Huff said later that he learned more about art from Lee than from any other artist.2 He also learned how difficult a career in art can be; Lee was always worried about where the next months' rent would be coming from and was often late in paying Huff.3

In New York, Huff found that the Art Students League was not to his liking so he elected to spend more time at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design (then at 126 East 75th Street) even though it cost money; there he could concentrate solely on sculpture.4

Lee believed, as many did at that time, that any serious young artist should study for a time in Paris, thereby gaining experience and, perhaps, credibility. Huff needed little encouragement; he, and his three friends, decided early on to save their money so that they could all go to Paris together. This they were able to do, except for Paul Ogden, who had found himself a girlfriend and whose savings had taken a beating as a result.5

On to Paris

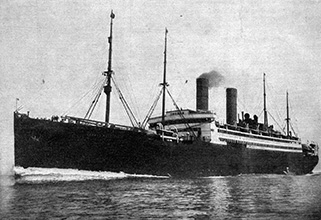

With the money the young men earned from The Miracle, they hoped that they could afford to stay in Paris for a year. The three left New York separately, with Huff being the last to depart, sailing on the SS George Washington1 in August of 1924.

Huff, Jones, and Davies rented an apartment at 9 Rue Delambre, near the corner of Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard du Montparnasse.2 They enrolled at the Académie de la Grande Chaumiere which was just a few minutes walk from their building. Huff's letters home often mention drawing classes he was taking but none provide any insight into his sculpture classes or with whom he studied. In a 1989 interview, Huff said that he did take sculpture classes, modeling the nude figure exclusively, and a 1930 newspaper article in the HFA states that Huff had studied with French sculptor Émile Antoine Bourdelle.3

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Arthur Lee with one of his sculptures, the torso of a youth, early 1925. Courtesy of Robin Lee and the Arthur Lee Foundation. Top right: The ship that brought Huff to Europe, the SS George Washington. This 1909 photo is in the public domain. Middle right: Looking southwest across Boulevard Montparnasse to Rue Delambre, the street on which Huff and his fellow art buddies lived. Their building was on the left side of the street—it's the one directly above the center of the white van just left of center. Note the Cafe Le Dome on the corner. Photo by David Smith. Bottom left: Ray Jones, one of Huff's friends (seated at left with the wide-brimmed hat) outside Cafe Le Dome in 1924. HFA. Bottom right: Cafe Le Dome as it looked in 2017. Photo by David Smith.

In a life drawing class, Huff recognized another friend from his San Francisco School of Fine Arts days named Basil Marros. Basil became one of the group and the four did everything together: go to school, dine, visit museums, attend concerts and art shows, and hike all over the city (often until the wee hours of the morning). They liked to spend Thursday afternoons at the Louvre.4

Nearing the end of their year in Paris, Huff, Jones, and Davies decided to visit Italy for a six-week period to study the works of the great masters. They explored the art and architecture of the country from top to bottom, stopping at Verona, Florence, Rome, and Naples. Jones and Davies ran out of travel money before Huff did; Davies went to England to visit relatives and Jones returned to Paris. Huff remained in Italy to see more of Rome, Naples, Pompeii, Pisa, and Milan, but he was back in Paris by the end of April 1925. In May, Huff left Jones in Paris and took a ship back to New York.5

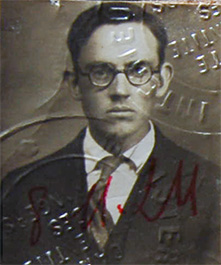

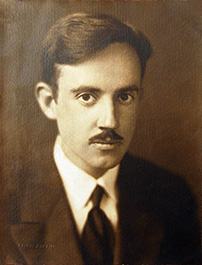

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Huff at Versailles, 1925. HFA. Top right: Huff (right) and Ray Jones on the Grand Canal in Venice, 1925. HFA. Bottom left: Huff's photo from his passport application, July 1924. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington D.C.; NARA Series: Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925; Roll #: 2597; Volume #: Roll 2597 - Certificates: 455850-456349, 08 Jul 1924-10 Jul 1924. Bottom middle: Photo of Huff from his French student ID, circa 1924. Note that Huff is wearing glasses here. Huff wore glasses all his adult life, but apparently didn't like to be photographed with them on, at least in promotional and newspaper photos taken during the 1930s. HFA. Bottom right: A portrait of Huff taken by Soichi Sunami, circa 1927.6 This is the first known photo of Huff with a mustache; he would keep it for the rest of his life. HFA.

Huff apparently did not put much value on the art training he received in Paris. He must have said as much in a January 1925 letter to Benny Bufano because in his response, Bufano wrote "I am very glad that you are thinking and that you realize the inferiority of the schools in Paris. This, of course, is not the case with all of their schools. However, there are very few, if any worth attending."7

Back in New York City

In New York, Huff reunited with his friend Paul Ogden, the one who did not go to Paris. They rented a loft at the corner of Sixth Avenue and 8th Street; this also served as their art studio. The location was convenient for Huff since it was just around the corner from Arthur Lee's MacDougal Alley studio and just a few blocks from Remo Bufano's marionette studio. Being the Prohibition era, speakeasies abounded, and, according to Huff, there was one a floor below their loft.1

Huff was to remain in New York City for about four more years, honing his craft and soliciting commissions. A good deal of his activities during this time can be pieced together, however, a precise chronology is difficult. He resumed working at Arthur Lee's studio but probably not as much as he had prior to going to Paris; he was now a young sculptor pursuing his own projects. Still, Huff apparently continued to take sculpture classes at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design.2

Huff was told that a wealthy San Francisco woman, one Mrs. Meyer—possibly a Huff family friend—wanted to meet Arthur Lee. Huff arranged the meeting, during which Lee sang the praises of William's work. Mrs. Meyer was so impressed that she decided to support the young sculptor, sending Huff $75 every month for two years3—adjusted for inflation, that's over $1,000 per month in 2019 dollars.

Despite this income, Huff, for a time, worked for the Edel (sp.?) Company enlarging monuments but quit because he didn't enjoy working with other people's sculptures. However, he admitted that the work proved to be good training for later projects such as the Chief Solano monument.4

Also during this period in New York City, Huff became proficient at modeling animals, a skill that was to come in handy later. He wrote:

It all started at the Bronx Zoo in New York, 1926. One morning I went to the zoo office and asked for permission to enter two hours before opening time to enable me to work without distractions from visitors. I was issued a pass and from then on I spent many hours modeling and sketching the animals from life. I kept a portable modeling stand in a store room at the Lion House; became a good friend of the keeper who helped me out in many ways. My stand was put together with bolts and wing nuts and could be assembled in ten minutes—and easily transported anywhere in the park to the cage of the animal I was interested in studying. The animals that "posed" for me were the rhinoceros, African elephant, bison, leopard, giraffe, eland, springbok, hippopotamus, aoudad, and many more. The most entertaining animal of all was "Khartoum," the African elephant. He took delight in throwing dung (his) over the high plate-glass wall at the spectators—especially if they were in a group."5

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Some of the sculptures that Huff modeled from live animals at the Bronx Zoo. From the left are a giraffe, African elephant (probably Khartoum, whom Huff describes above), hippopotamus, rhinoceros, aoudad and springbok. Regarding the rhinoceros, Huff said "This was the first animal to 'pose' for me. I remember how he stood like a professional model—as if he were being paid." Quote from a page in Huff's informal autobiography; all photos from the HFA.

Huff was to make many medallions bearing fantastic masks in his lifetime, but his first series was made for an all-marionette production of playwright Emjo Basshe's6 Fantasy in Flutes and Figures that Remo Bufano put on at his Marionette Theatre in May 1926. Bufano must have introduced Huff to Basshe well before this—Huff had visited Basshe at the playwright's home in Rock Tavern, New York, about 70 miles north of New York City—as early as June 1925.7

Huff may have received a number of commissions while in New York. An Oakland Tribune newspaper clipping, circa 1957, in providing some background on Huff, reported that "he opened a New York studio where he executed portrait busts and heads, public monuments, statues and varied sculptures for eastern clients," however, this may be a blanket description that includes Huff's later Bennington, Vermont, projects (see the next subhead).8

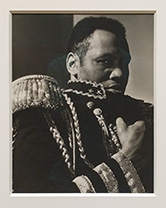

In 1927, Huff sculpted a smaller than life-size head of actor/singer Paul Robeson,9 but it was not a commission. Huff chose to make the portrait simply because he thought Robeson had striking features.10 Huff must have been pleased with the piece because he entered it, after getting permission from the Robesons, into an art exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. The Robeson head was exhibited there for most of 1928 and all of 1929.11 This piece and a bronze leopard (the only known Huff sculpture with a date on it), probably one of the animals Huff modeled at the Bronx Zoo and also made in 1927, are the oldest Huff bronzes known today.12

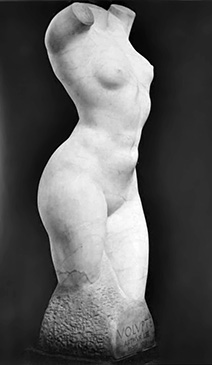

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Volupté, a sculpture that Arthur Lee completed in 1915 while living in Paris, earned Lee a Widener Gold Medal in Philadelphia in 1924. Courtesy of Robin Lee and the Arthur Lee Foundation. Top middle: Lee's piece may have been the inspiraton for Huff's own Volupté-like sculpture, albeit on a much smaller scale. Lee's piece was just shy of four feet in height; Huff's was only 6.5 inches high. Huff's piece was probably made while under the tutelage of Lee, but since Huff almost never dated any of his work (only one sculpture is known to have a date on it), we can only speculate. AHR. Top right: This standing female nude was the first sculpture Huff made after returning from Paris. HFA. Bottom left: Huff's bronze of Paul Robeson. AHR. Bottom middle: "Paul Robeson as the Emperor Jones," a 1933 photograph by Edward Steichen. Photo taken by David Smith at a Whitney Museum of American Art exhibition, September 11, 2016. Bottom right: Aside from a few historical plaques, Huff's leopard bronze is the only dated sculpture (1927) of which I am aware. Photo by Mark Humpal.

After reading a book on the life of American military officer, explorer, and politician, John C. Fremont, Huff was inspired to create a large equestrian bronze of the man. In an April 21, 1928, letter home, Huff wrote "my belief is so absolute that I myself am going to start the ball rolling and make the first big monument to Fremont. Any man, any group of men or any society can have it just for the cost of the bronze, and they can erect it in any spot in California they choose. However, I should prefer having it erected in San Francisco. I have such an overwhelming desire to get going on this piece of work that I can't concentrate on anything else."13 There is no evidence that Huff actually modeled the Fremont sculpture at this time, however, he would revisit the plan many years later and produce one (see the photo on page 6).14

Bennington, Vermont

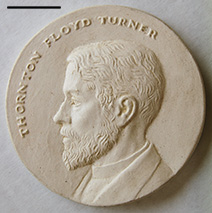

According to Huff, he had a friend in Vermont whom he visited at some point during this New York City period,1 probably in late 1928 or early 1929. Who the friend was is unknown, but during Huff's visit or visits, he made some good contacts in the Bennington area and was able to line up some commissions very quickly. His abilities came to the attention of one of the wealthiest women in the area, Eliza Hall Park McCullough (1848-1938), widow of former Vermont governor, John G. McCullough (1835-1915).2 Mrs. McCullough and at least one of her daughters engaged Huff to do "portraits" of family members. Based on correspondence in the HFA, the majority of these portraits were reliefs on medallions, however, he may have done at least one three-dimensional bust as well.3

Click on any image to see a larger version. All three of these medallions were made by Huff during his time in Bennington. The scale bars are one inch. Left: Thornton Floyd Turner was rector of St. Peters Church in Bennington at the time of his death in 1919. HFA. Center: Collins Millard Graves served several years as Bennington postmaster in the early 1900s. HFA. Right: Colonel Alonzo N. Clark, a Bennington resident and Civil War survivor. Huff made a plaster medallion of the Colonel that is still in the Bennington Museum's collections. HFA.4

During his time in New York City, Huff befriended the Bachers—Mary Holland Bacher, widow of Cleveland artist Otto Henry Bacher (1856-1909), and her four sons. Two of the sons, Holland Robert and Will Low Bacher, ran White Cloud Pottery in Rock Tavern, New York, the same town where Emjo Basshe lived; it's possible that Huff came to know the Bachers through Basshe during his visits to the playwright's home. Huff had the Bachers cast a number of medallions for him and perhaps other pieces while in NYC. Prior to moving to Rock Tavern in 1917, the Bachers had lived in Bronxville, about 15 miles north of New York City; they must have held onto the Bronxville property because Huff remembered visiting them there and having cookies and coffee with their neighbor Elizabeth Bacon Custer, widow of General George Armstrong Custer.5

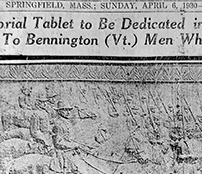

Huff began spending more and more time in Bennington in the fall of 1929. By December, he had moved there, obtaining studio space in the Cone Building at 433 Main Street.6 By this time he was already in talks with John Spargo of Bennington's Battle Monument and Historical Association to create a bronze Civil War memorial plaque for the town, a project that may have been Huff's idea.7 After a good deal of red tape, the last contract for the Civil War memorial was finally signed in April, 1930. By then, Huff's design had already been approved and was being prepared for casting in bronze. The memorial was dedicated in front of the Bennington Museum on a Saturday in August, 1930; it can still be seen there today.8 This was to be the first of a great many historical bronze plaques that Huff would create in his lifetime.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: April 6, 1930, Springfield Union News and Sunday Republican article on the upcoming dedication of the Civil War monument at the Bennington Museum. HFA. Center: The memorial as it looks today. Photo courtesy of HMdb.org; photo by Bill Coughlin. Right: This article in the HFA may have accompanied the newspaper photo at far left.

Perhaps one outcome of Huff's work on the Civil War memorial was his making the acquaintance of Eugene B. Bowen (1874-1964), a Cheshire, Massachusetts, businessman and vice president of the Berkshire County Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution. Whether it was Bowen's idea or Huff's is unknown, but the two men became convinced that a memorial honoring the Massachusetts volunteers at the Battle of Bennington was needed. More than likely, Huff spoke to the Bennington Historical Society and got them enthused about the plan too; before long, they were working on their own memorial to honor the Vermont soldiers. Naturally, both parties wanted to have their memorials placed at the site of the battle so the state of New York had to be brought into the discussion. This is because the battle was actually fought in New York—at Walloomsac Heights, about ten miles from Bennington.

With New York approving of the plan, the project moved forward remarkably fast. Huff had wasted no time in researching and creating a plaster bas-relief representing the Massachusetts volunteers; he had it finished even before the governor of Massachusetts named the commission (chaired by Bowen) to supervise the Bay State's contribution. Representatives of the three states gathered at Walloomsac Heights on Saturday, August 15, 1931, to dedicate the memorials.9

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: An article from the Sunday, August 16, 1931, edition of the Springfield Union News and Sunday Republican about the Bennington battlefield monument dedication. HFA. Top center: The Revolutionary War monument at Walloomsac Heights. Photo courtesy of HMdb.org; photo by Bill Coughlin. Top right: Another piece on the dedication from The Knickerbocker Press, Sunday, August 16, 1931. HFA. Bottom left: Huff's Civil War plaque in Bennington, Vermont. Photo courtesy of HMdb.org; photo by Bill Coughlin. Bottom right: Huff's Revolutionary War plaque at Walloomsac Heights, New York. Photo courtesy of HMdb.org; photo by Bill Coughlin.

Bowen would become quite a supporter of Huff. Bowen, a graduate of and donor to Tufts University, engaged Huff in 1931 to create a bas-relief of the late Charles Ernest Fay, a professor of Modern Languages at Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts, for more than 60 years. The piece was made following Fay's death in January 1931 and was installed in Goddard Chapel on the Tufts campus sometime after June 1934.10 The Fay plaque can still be seen today, just one of many lining the Chapel’s interior walls.

In late 1933, Huff and Bowen started thinking about a statue of a soldier to commemorate the Massachusetts volunteers that fought in the Battle of Saratoga in New York State, about 36 miles west of Bennington. As a representative of the Sons of the American Revolution, Bowen began lobbying the Massachusetts legislature for the passage of a bill supporting the creation of the monument. Huff made a model of the proposed statue, as well as a rubbing of a companion bas-relief for Tufts University, and sent them to Bowen in January 1934. Bowen wrote the following month, "I was in Boston last week and I saw several of the men who are in the legislature. They all talked favorably about the Saratoga monument and I think by keeping at it I'll get the bill through. Your miniature is very favorably commented on by every one who has seen it."11 The bill failed to pass in 1934, but Bowen vowed to continue pushing for its passage. He kept trying through at least June of 1938.12 Bowen's efforts were apparently in vain as there is no evidence that the monument bill went through. More than likely, the bas-relief did not get funded either.

Bennington Marionette Theater

In early 1930, Huff chose to use the skills he learned while working with Remo Bufano in New York City, and organized the Bennington Marionette Theater, enlisting a small group of talented locals. Huff built most of the puppets, a portable stage, and most of the scenery for their productions. The theater had eight members at the time of their first show. The North Bennington High School orchestra provided the music (with, at times, a marionette conductor). The group would give both public and private performances in the Bennington area and received local newspaper coverage. They had an eight-play repertoire, "The Coq Brothers" being the first.1

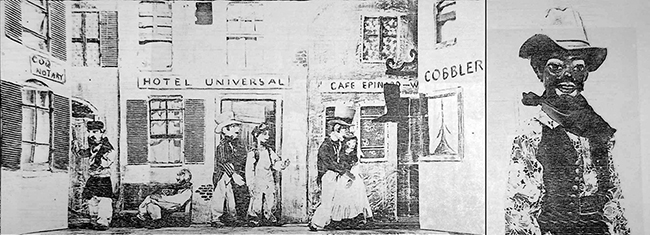

Click on either image to see a larger and complete version. Top: An assortment of articles, probably from The Bennington Banner, about Huff's Bennington Marionette Theater. HFA. Bottom: A couple sets and one figure from presentations put on by the Marionette Theater. HFA.

Marriage and return to California

Huff met his future wife in the Cone Building where he had his studio. The building housed several other businesses, including the Noveck Studio, a music store where Bennington resident Doris Mackintosh worked. The story is that the two first met at the water fountain in the hallway. Huff would marry Ms. MacIntosh on November 3, 1931.1

William and Doris MacIntosh Huff left on their honeymoon not long after the wedding and took their time driving across the country in a Model A Ford to Berkeley, California. The motivation for that honeymoon drive was simply to visit Huff's family, but Bill and Doris never went back to Vermont. As Huff explained it, "On my return to California I renewed old contacts—and as luck would have it I got a series of breaks. It was during the Depression and since everything was going my way we decided to remain."2 They would live at a number of Berkeley addresses over the years; at one point they spent two years in Concord. But in 1942 they made their final move to a house in Alamo and remained there for the rest of their lives.3 The Huffs had three children—Antonia, Tim, and Colin—all born during the Berkeley years.

Click on any image in the top row to see a larger version. Top left: A plaster medallion with the likeness of Doris, Huff's wife. It measures about four inches across. HFA. Top, second from left: A ceramic plaque of Huff's daughter Antonia. This plaque, and the plaques of Antonia's brothers, are about ten inches across. HFA. Top, third from left: A ceramic plaque of Huff's eldest son Tim. HFA. Top right: A ceramic plaque of Huff's son Colin. HFA. Bottom: Huff with his siblings on the front steps of the sisters' house at 2706 Fulton Street, Berkeley, circa early 1930s. Back row, from the left: William, Olney, Tom. Front row, from the left: Alberta, Nellie, Pearl, Mary. HFA.

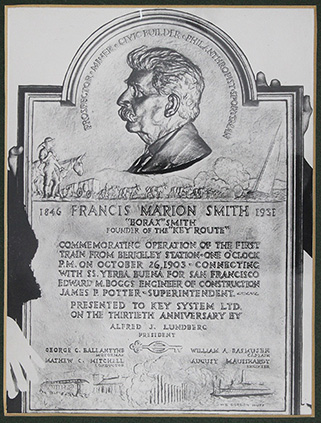

Just what the "series of breaks" Huff refers to above is something of a mystery; it wasn't until 1933 that we learn of Huff's first California commission. This first work was a plaque of Francis Marion "Borax" Smith, founder of the Key System.4 The Key System was the predecessor of AC Transit, providing mass transit throughout much of the East Bay from 1903 through 1960. Huff's plaque, presented to the Key System on October 24, 1933, was placed in a marble niche in the lobby of the System's offices at 1106 Broadway in Oakland. In 1963, AC Transit was moving to new offices and during the move, the plaque was stolen.5 In 2011, someone wanting to sell the piece contacted an Oregon art dealer—the seller had photos of the plaque so it seemed to be a genuine offer. Unfortunately, the seller got cold feet and has not been heard from since; the whereabouts of the plaque remain a mystery.6

Although the original plaque was lost, a replacement was produced in 1974. That year, Ray Hannah, one of Huff's former colleagues at the Alameda Naval Air Station and a railroad buff, tracked down Bill (he'd retired six years earlier) and asked him about the Smith plaque. The Oakland Tribune had this to report:

He [Bill] told Hannah, "Yes, yes, I have the plaster cast of the bust." But then he remembered he also made a second casting in bronze of the bust and buried it in his backyard, hoping this would age the metal. "He forgot all about it, Hannah said, "until I asked him about it."

The Naval Air Station Employees Association is having a plaque made containing the words on the original plaque.7

The plaque was to be mounted at the Bay Area Electric Railroad Association’s streetcar museum, now the Western Railway Museum, 5848 State Highway 12, Suisun City. Huff’s cast can be seen there today, however, a duplicate of the original plaque with its text was never made.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: This article from the Fresno Bee, that was published prior to the dedication of Huff's Revolutionary War monument in August 1931, is of interest because the photograph shows Huff working on a bust of the woman he would marry in November, Doris Louise Mackintosh. HFA. Right: Huff's first commission upon returning to the Bay Area, a plaque commemorating the 30th anniversary of the inauguration of the Key System and its founder, Francis Marion "Borax" Smith. HFA.

Chief Solano and jobs that followed

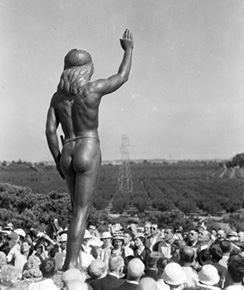

The next known Huff California work is perhaps his best known, a 12-foot-high bronze statue of Chief Solano. But it wasn't a commissioned piece—the work was the result of Huff's winning a contest.

In 1933, a California Division of Parks commission was organized to oversee a competition for a statue of Chief Solano, i.e., Suisuni Indian chief Francisco Solano (the name given him by missionarys), the namesake of Solano County who died in 1850. Huff entered the competition, needing to submit a small model by noon, February 15, 1933. About 17 sculptors competed. Huff won the competition and worked on the full-size statue at Oakland's Louis de Rome Memorial Bronze, Brass and Bell Foundry on 50th Street.

A dedication ceremony, attended by an estimated 3,000 people, was held on June 3, 1934, on a rise four miles west of Fairfield, north of the I-80 CHP truck scales (near the Solano Community College Fairfield campus). Because of continued vandalism, Chief Solano was moved to the Solano County Events Center at 601 Texas Street, Fairfield, where he stands to this day.1

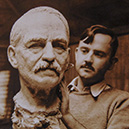

Except for the middle left and center images, click on any to see a larger version. Top left: Huff at the de Rome Foundry with the finished clay sculpture of Chief Solano. HFA. Top center: Preparing to remove the mold from the piece. HFA. Top right: Huff with the finished bronze statue. HFA. Middle left: A crowd has gathered for the unveiling at the dedication ceremony. HFA. Middle center: Chief Solano is revealed. HFA. Middle right: Huff poses with the Chief. HFA. Bottom left: An article about Huff's accomplishment that appeared in Vermont's Bennington Banner newspaper. HFA. Bottom right: Chief Solano in his current location outside the Solano County Events Center at 601 Texas Street, Fairfield. Photo by David Smith.

The media attention generated by the Chief Solano statue and Huff's relationship with the de Rome Foundry helped make finding work easier. In 1936 (and possibly earlier) Huff was "doing modeling work" for de Rome.2

As we have seen from his accomplishments in Bennington, Huff was adept at generating projects that would benefit both the community and himself. In May of 1935, Huff came up with an idea to create busts of noteworthy Californians for a "California Lane of Fame" and he looked into government funding for the project.3 Apparently Huff's plan did not generate a lot of interest, and certainly not funding, so he attemped a smaller-scale version of the project—instead of statewide notables, he'd focus on prominent East Bay citizens.4 Based on photos in the Huff archives, Huff went ahead and made at least a few plaster busts, but there is no evidence that his efforts to raise funds for this smaller project fared any better than the first. However, Huff was not yet willing to give up on the idea.

On April 8, 1935, the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act was enacted as part of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. This established the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a public works program for the jobless.

In 1936 or early 1937 Huff was "approached by a good friend, Worth Ryder, professor of art at U.C. who was associated in some capacity with the WPA Art Project. He knew I had a sizable studio on Hearst Avenue, Berkeley, and suggested to the head of the project, who was looking for a place to locate six workers, that maybe I could accommodate them. He had asked me earlier if I could and my answer was affirmative. … I was duly put on the payroll. I submitted a proposed project which was approved—making portrait heads of pioneer notables. The assigned WPA workers mixed clay, built standards and then sat around drinking coffee while I modeled. (The conviviality was very enjoyable, especially on rainy days). With some instruction and assistance they were able to make plaster casts of my creations."5 The heads pictured below were probably created for Huff's two projects: East Bay notables and U.S. pioneer notables. All the heads are of plaster; Huff had no photographs of finished bronzes and there was nothing in the HFA to suggest that casting in bronze ever took place for either project.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Some of Huff's busts of "notables." In the top row, from the left, are author Bret Harte, author Jack London, Huff working on his bust of educator Philip M. Fisher, the finished Fisher bust, and a figure Huff identified as "Dr. Nicholson" (most likely astronomer Seth Barnes Nicholson). In the bottom row are, from the left, miner, businessman and Key Route founder Francis "Borax" Smith, poet and frontiersman Joaquin Miller, philosopher and historian Josiah Royce, an unknown figure, and Abraham Lincoln. HFA.

In an effort to gain more name recognition, Huff would enter his sculptures in shows and exhibits. In summer 1936 Huff entered a work entitled "Saber-tooth Tiger" (Charles Camp's influence perhaps; see "The UCMP Connection" below) in the Oakland Art Gallery's annual exhibit for sculptors. A year later Huff entered a piece in the San Francisco Art Association's annual exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Art. H.L. Dungan, a writer for the Oakland Tribune, described Huff's entry: "'Nell,' a portrait head in terrazzo, which, in our opinion, is one of the best in the show. Nell wouldn't make a Hollywood beauty, but she has great beauty of character and a gentle, gracious smile one seldom sees in sculptures. That smile is worth going to see. We went several times."6

The UCMP connection

The exact circumstances of how Huff and UCMP's Charles Camp met are unknown, but some good guesses can be made. Following Camp's death in 1975, a booklet he wrote on Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada, was published posthumously; a preface stated that Huff and Camp had been friends for 40 years.1 The theory that they met in December 1935 is supported by correspondence in the HFA. Their initial introduction was probably arranged by Ansel Hall, head of the National Park Service's Field Division of Education, or Natasha Smith, a Masters student in the Department of Paleontology who was doing some work for Hall in the mid 1930s.

In the early 1930s, Ansel Hall worked out of an office in Hilgard Hall on the Berkeley campus but also had workshop space at 1836 Euclid Avenue just north of campus (near where LaVal's Pizza is today); using federal relief funds, Hall hired a crew of workers (one of them being Natasha Smith) to assist with models, relief maps, and dioramas for the park system. Hall sought the expertise of UCMP when his crew began work on a number of prehistoric animal models. In a February 1934 letter, UCMP Director Charles Camp reported to museum benefactress Annie Alexander that he was "working with Ansel Hall's crew of sculptors and modelers on restorations of miniature models of phytosaurs, Moropus, elephants, etc. For this we are promised a complete set of the casts when the work is done. Miss Natasha Smith is developing into quite a sculptress."2

In December 1935, seeking work, Huff visited Hall. At the time, Hall did not have the funding to hire more sculptors, but one month later Hall's office reported that they'd soon be coming into some "considerable money" and that Huff should fill out an application to get on Washington's list of eligible artists, as the NPS could only hire artists from the list.3 There is no evidence to suggest that Huff continued to pursue a job with Hall, the most likely reason being that he had met Camp. Although Huff was never hired on as a full-time employee with the Department of Paleontology, he apparently was satisfied that he'd have enough work to make ends meet. Huff and Camp hit it off and thus began a long and mutually beneficial friendship.

The earliest record of his working on a project for Camp comes in Huff's informal autobiography. Huff reported that he was producing plaster casts of fossil bones for UCMP, at the request of Charles Camp, assisted by a few WPA workers.4 This cast-making for Camp probably began in early 1936. One of the plaster casts that Huff helped with was the skull of the Triassic dicynodont Placerias. In fact, it was this particular cast that Huff was wrestling with when he got the go-ahead to begin work on the Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE) paleontology exhibits in early 1938.5

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: This photo of Ansel Hall's workshop on Euclid Avenue, dating from 1933, must have been taken just a short time before Charles Camp wrote to Annie Alexander about the Department's work with Hall (see the paragraph above) because that's Natasha Smith on the left working on a model of Moropus. The other people are, from left, Lorenzo Moffett, Paul J. Fair (supervisor) and Cecil Tose. From the Western Museum Laboratories photo files, National Archives, College Park, Maryland. Right: This cast of the dicynodont Placerias currently resides in UCMP's collections. Perhaps it's one of those that Huff helped with. Photo by David Smith.

Page 2 of this feature on William Gordon Huff will focus on the sculptor's work for the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940.