A UCMP special exhibit

The Art of Sculptor William Gordon Huff

Part II: The Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939-1940

Open the Sources page for Part II in a new tab/window.

Beginning around early 1936 Charles Camp put Huff to work making plaster casts of fossil bones for the UCMP, with some of it being done at Huff's studio on Hearst Avenue. Camp and Huff became good friends, perhaps bonding over their shared love of history (Camp's "other profession" was historian of the American West). Huff's affiliation with the museum put him in just the right place at the right time. With the opportunities presented by the coming of the Golden Gate International Exposition, Huff would jump from humble maker of plaster casts into the most noteworthy project of his lifetime.1

To commemorate the recent openings of both the San Francisco-Oakland Bay and Golden Gate Bridges, a celebration—the Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE)—was prepared for 1939. General planning for the fair's buildings and content began in late 1934. Milton Silverman, a biochemist and research associate at the University of California medical school, and later, science editor for the San Francisco Chronicle, was named Director for the fair's Hall of Science. In early 1937 he contacted educational and research institutions around the West hoping to generate interest in the Hall. University of California President Robert Gordon Sproul responded with an offer to create an exhibit for the biological and physical sciences which came to be called "Science in the Service of Man." The fair was to run for about eight months, opening on February 18 and closing October 29.2

This caught the attention of Huff who wasted no time in drawing up a plan for a paleontology exhibit. Camp loved the design and immediately forwarded it to Silverman, however, the pair were jumping the gun a bit: a committee to handle such submissions had not been formed as yet. By August 1937 an exhibits committee, headed by T. Harper Goodspeed of the UC Berkeley Botany Department, was in place and Camp resubmitted Huff's plan.3

Huff's monumental sculptures

A month before Camp resubmitted the paleontology proposal, Huff became one of several lucky Bay Area sculptors selected to design monumental sculptures for the GGIE, possibly thanks to the influence of his friend, UC Berkeley art professor Worth Ryder. Huff signed two contracts (July 26, 1937) to create models for large figures destined for (1) the fair's Tower of the Sun and (2) the Court of Flowers and Arch of Triumph. He was required to provide his finished plaster casts—four 1/4-size models for the Tower of the Sun and two 1/2-size models, one for the Court and one for the Arch—by December 30th.1

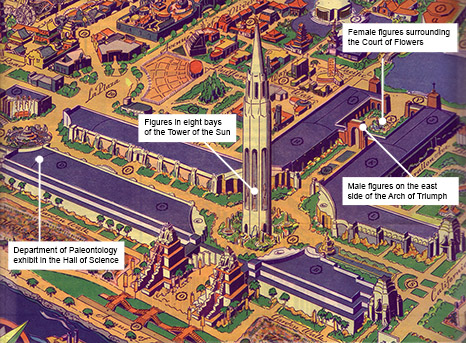

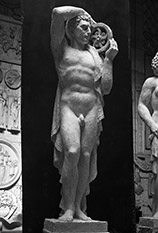

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: The locations of Huff's monumental pieces and the paleontology exhibit at the GGIE. Adapted from a map in San Francisco Bay Exposition. Official Guide Book: Golden Gate International Exposition, World's Fair on San Francisco Bay. Crocker-Union, San Francisco. 1939. Right: This sculpture may have been an early version of Huff's figure representing "The Arts" in the Tower of the Sun. HFA.

For the Tower of the Sun, Huff provided four figures representing Agriculture, Industry, Science and The Arts. His 4.5-foot-tall models were enlarged to 20 feet and duplicated to fill eight bays in the lower portion of the octagonal Tower.2

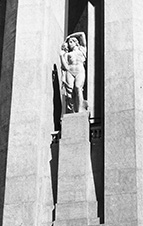

Huff made a 6-foot tall male figure that was enlarged to 12 feet and duplicated. The two "men" decorated buttresses on the east side of the Arch of Triumph, the portal leading from the Court of Flowers to the Court of Reflections. The perimeter of the Court of Flowers had 28 buttresses surmounted by 9-foot-tall female figures designed by Huff (his original models were 4.6-feet tall). All of the Huff-designed figures probably received a coating of some kind to resist the elements. It may have been something like that used on structures at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition which were "covered in a specially blended, ivory-hued plaster that incorporated gypsum and hemp."3

Once Huff's models were approved in March 1938, professional plaster men took it from there and created the full-size figures. All the enlargements were done by August Dackert & Co., architectural modelers and sculptors, located at 1450 15th Street in San Francisco. Huff's contract then required him to "supervise, criticise [sic], retouch and assist in the perfecting of the full size models." This stage may have overlapped a bit with his work on the paleontology exhibit, approved just a couple of months later. Huff received $4,000 for his monumental sculptures; that's the equivalent of over $72,000 in 2019 dollars.4

The response to Huff's monumental sculptures was mixed. Eugene Neuhaus (1879-1963), the first head of UC Berkeley's art department and who taught there for over 40 years, wrote "One must note that although Mr. Huff's work is sound, and rich in craftsmanship, it is somewhat lacking in inspiration. It is dignified but not dynamic, pleasing rather than stimulating. His scale and craftsmanship seem adequate to the requirements of the tower, and the opulent quality of these statues adds a sense of richness to the sober architectural surfaces of the tower structure."5

The Oakland Tribune reported in February 1938 that Harris Connick, the new director of the GGIE, upon seeing photographs of models of sculptures planned for the fair declared "They're terrible!" Apparently he was distressed at the amount of nudity represented. Connick felt that the sculptures "would make mothers hurry the kiddies past, and make strong men blush." Regarding Huff's figure representing Agriculture, Connick said that the "full-figured goddess … could use more drapery than a few limp stalks of wheat strategically placed."

The Fresno Bee said that Connick compared Huff's four Tower of the Sun figures to "a quartet of women, possibly of questionable character, fleeing a rooming house fire in their nighties." Connick must not have looked at the photographs of the figures very carefully since two of them are male. In the same article, Connick praised Huff's male (and fully clothed) figure planned for the Arch of Triumph.6

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top: From left, Huff's scale models of Agriculture, the Arts, Industry and Science for the Tower of the Sun. HFA. Middle: From left, the scaled-up Agriculture figure next to Huff's orginal model, three photographs of Huff applying finishing touches to the enlarged Arts figure, and Huff doing the same to the Science figure. The Agriculture figure is from Eugene Neuhaus. The Art of Treasure Island: First-hand Impressions of the Architecture, Sculpture, Landscape Design, Color Effects, Mural Decorations, Illumination, and Other Artistic Aspects of the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939. UC Press, Berkeley. 1939. P. 101. The other four photographs are from the HFA. Bottom: From left: The final Arts figure in position in the Tower of the Sun; the Science and Industry figures in the Tower; the Industry, Agriculture and Arts figures in the Tower; and the Tower of the Sun illuminated at night. The first three photographs are from the HFA, the fourth is by Gabriel Moulin, © 1939 San Francisco Bay Exposition.

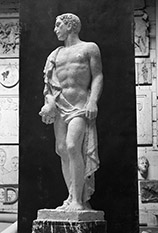

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Huff's scale models for the male Arch of Triumph figures and the female Court of Flowers figures. HFA. Second from left: Huff with rows of the scaled-up female figures destined for the Court of Flowers. HFA. Third from left: One of the 28 female figures positioned around the perimeter of the Court of Flowers. HFA. Fourth from left: Two of the female figures in a corner of the Court of Flowers. From Eugene Neuhaus. The Art of Treasure Island: First-hand Impressions of the Architecture, Sculpture, Landscape Design, Color Effects, Mural Decorations, Illumination, and Other Artistic Aspects of the Golden Gate International Exposition of 1939. UC Press, Berkeley. 1939. P. 25. Right: One of the 12-foot-tall male figures in place on the Arch of Triumph. HFA.

The paleontology exhibit

Huff's design originally called for five "life size groups of the magnificent prehistoric animals of the West, arranged in educational, artistic and dramatic form in replicas of their natural surroundings." There would also be mounted skeletons of the animals depicted in the life-size groups, a free-standing sculpture of Felis atrox attacking Bison latifrons, and more. The estimated cost of this exhibit was put at $42,000, more than one fifth of the university's entire budget; and it would require 10,000 square feet, while the entire "Science in the Service of Man" space allotment was only 12,000 square feet! Needless to say, this plan was not going to fly.1

The floor plan for the University's "Science in the Service of Man" exhibit. Note how much space Paleontology was given compared to the other departments. Adapted from a plan in University of California Committee on Cooperation with the Golden Gate International Exposition. Science in the Service of Man: Exhibits in the Basic Sciences, San Francisco, 1940.

The exhibits committee was impressed with the design but suggested that the scale of the entire plan be reduced significantly. So Huff and Camp made several changes. The life-size animal dioramas were reduced to one-sixth size but a sixth diorama was added. The free-standing sculpture of Felis atrox and Bison latifrons became a 13x7-foot bas-relief and the mounted skeletons were eliminated altogether. Instead, Huff proposed "five full-sized head restorations as pedestal units," as well as a branching tree of life depicting vertebrate evolution and a display on the evolution of the horse.2

Arrangement of the paleontology displays in 1939, based on photographs. The Paramylodon head, Synthetoceras head and the bas-relief are grayed out because their locations cannot be established with any certainty. The museum found itself with some leftover space so two display cases were filled with Rancho La Brea and Bay Area fossils.

When the paleo exhibit was finally approved, sometime around May of 1938, Huff started right in on making the Smilodon figures for the Pleistocene diorama.3

Now a painter was needed for the diorama backgrounds. Charles Camp had originally proposed hiring the famous paleoartist Charles R. Knight to do the backgrounds but it is unknown whether Knight's services were ever requested or not.4 In the end, William J. Norton,5 the university's Executive Officer for the Committee on Cooperation with the Golden Gate International Exposition, hired Ray Stanford Strong, an experienced diorama painter, away from the U.S. Forest Service. Strong had been working on dioramas for the Forest Service for three years and had also done dioramas for the San Diego Exposition of 1935.6

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Charles Camp in 1946. From the cover of the May 1946 issue of The Pony Express, Vol. 12, No. 12, Placerville, California. Top center: Grad student V.L. VanderHoof (right) takes measurements on the skull of a desmostylan for Huff (left). The skull was used in the small Contra Costa County fossils display for the first year of the GGIE. From the Large Format Negative Collection, UA. Top right: Landscape painter Ray Strong circa the 1930s or 1940s. RSFP. Bottom: The paleontology displays greeted visitors to the "Science in the Service of Man" exhibit. The six dioramas and three of Huff's life-size heads are visible. From University of California Committee on Cooperation with the Golden Gate International Exposition, Science in the Service of Man: Exhibits in the Basic Sciences. Hall of Science, Golden Gate International Exposition 1939-40 (San Francisco, 1940).

Huff described his work on the paleontology exhibit:

In developing our work for the Univ. of Calif. Exhibition, 'Science In The Service Of Man,' we worked with U.C. paleontologists and geologists. Dr. Charles L. Camp was head of the Department of Paleontology and director of the museum. In creating the prehistoric animals I worked closely with him, Dr. R.A. Stirton and others [such as Samuel P. Welles and V.L. VanderHoof. I made all the animals and Ray Strong the landscape paintings. Bill Norton, manager of the university and through whose hands flowed the money appropriated by the state for the U.C. Exhibition, was very cooperative. He provided me with a graduate student of paleontology, Howard Anderson, whose job it was to furnish me with skeletal measurements (1/4 scale) [actually, 1/6th scale] of all the animals I restored. Also, as requested, Bill hired John Frederick to do most of my plaster casting. The services of these two men helped me speed up production.

The last six months before the Fair opened found me working twelve hours a day including Saturdays and Sundays. I was glad when it was all over, but it was worth it financially and spiritually with emphasis on the former.7

Huff neglected to credit two women who also helped with the preparation of the six dioramas: A September 6, 1938, Oakland Tribune article included a photograph in which "Huff is directing Mrs. Pattie Jackson and Miss Emma Jordon [sic; actually, Jordan] in preparing dioramic studies in which early California denizens will be shown in what might have been their contemporary surroundings." According to Ray Strong, the two women worked on the plaster diorama foregrounds.8

The primary display for the 1939 paleontology exhibit was called "Up Through the Ages: Restorations of Ancient Life in Western America." This included the six dioramas, the five life-size heads on pedestals, and the bas-relief. Each diorama was to measure about eight-feet wide by five-feet deep by six-feet-four-inches high; these measurements include the wood framing. Ray Strong described the making of the dioramas:9

It was my job to re-create primarily the mood and action in ancient landscapes that led to their [the animals and plants] burial and fossilization.

Our major and new departure in this project grew out of Mr. Huff's outstanding abilities as an animal sculptor. To give maximum vitality to his animals he put emphasis on bone action and muscular qualities. We soon realized for unity of effect, that my painting had to emphasize sculptural quality too. I did this by simplified handling of big basic planes of form.

We sculpted foregrounds in plaster, whether grass, rocks, stream beds or banks, carefully relating rythmn [sic] and treatment to a total unified mood-concept. My painting tie-ins repeated the sculpt [sic] forms of grass, rocks and earth in close values of subtle earth colors. No detail colors were used in the eyes of the animals; they were simply wax-rubbed in umbers, terre verte or sienna …. Fair visitors and scientists alike, praised the results as highly realistic.10

The six dioramas

Huff produced a good 43 or so prehistoric animal figures to populate the six dioramas:

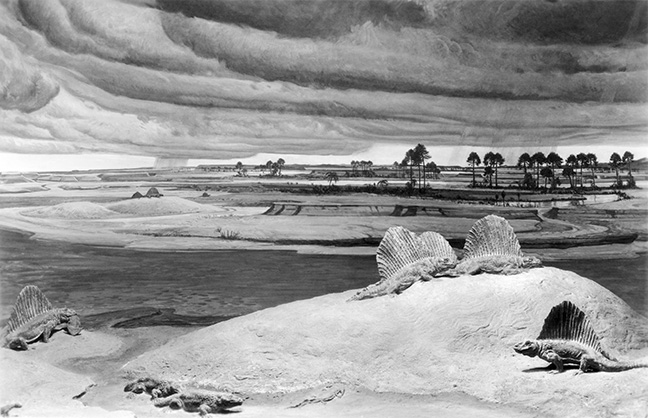

The Permian diorama depicts a flood plain during a passing storm in what is now Texas. Populating the scene are three Edaphosaurus, two Dimetrodon, two Diplocaulus, two Eryops and one Araeoscelis.1

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Top: The Permian diorama. Middle left: A close-up of the left side of the scene, featuring (from left) the lizard-like Araeoscelis, the sphenacodontid Dimetrodon with a leptospondyl amphibian (Diplocaulus) in its mouth, two temnospondyl amphibians (Eryops), and a second Diplocaulus. Middle right: The right side of the diorama. Diplocaulus is at the lower left. Three Edaphosaurus, edaphosaurid synapsids, bask on a sand dune while Dimetrodon eyes them from below. Bottom: From left are Araeoscelis, two Eryops, Diplocaulus, Edaphosaurus and Dimetrodon. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. These plaster maquettes of (from left) Araeoscelis, Eryops and Hyaenodon reside in the HFA. Hyaenodon appears in the Eocene diorama farther down the page but since these three are the only known surviving sculptural remnants of the GGIE dioramas, they are grouped together here. Photos by David Smith.

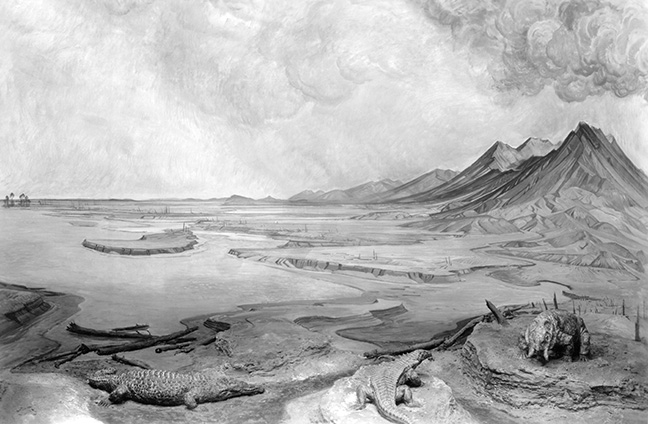

The Triassic diorama shows a flood plain in what is now the Painted Desert area of Arizona; the landscape has been burned and partly buried by volcanic ash. In the foreground are Machaeroprosopus, Desmatosuchus2 and Placerias. The restorations were based on fossils collected near St. Johns, Arizona.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top: The Triassic diorama. Bottom: The phytosaur Machaeroprosopus, the aetosaur Desmatosuchus, the dicynodont Placerias, the temnospondyl amphibian Metoposaurus, and a closeup of the right side of the diorama. For some reason, the Metoposaurus did not end up in the diorama (at least it's not visible in any of the photographs) although Huff had originally intended to include it. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

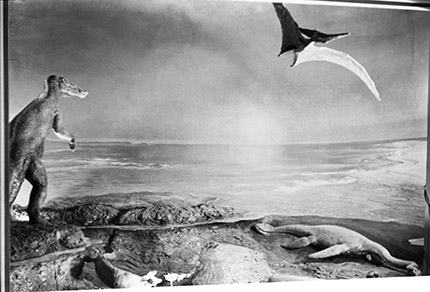

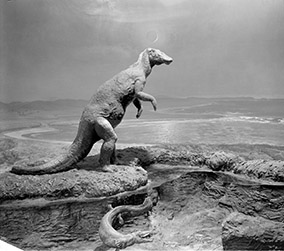

The Cretaceous diorama depicts a shoreline of a central California sea at night. Huff's figures include a mosasaur, the elasmosaurid plesiosaur Hydrotherosaurus, the flying reptile Pteranodon and a hadrosaurid dinosaur.3 With the exception of Pteranodon, whose fossils are fairly common in the American midwest, the restorations were based on fossils from California's San Joaquin Valley.

This was probably Huff and Strong's most ambitious diorama, in that it was a nighttime scene and viewers had to accept that they were looking through water to see the mosasaur and plesiosaur. Normally, the light would have been very dim but a bright light was used to take photographs of the diorama. If one assumes that all the animals in the scene are adults, then there is a problem of scale. Hadrosaurs could reach 30 feet or so in length; if the mosasaur is supposed to represent Plotosaurus (discovered in California in 1937), it was estimated to be 30 feet long as well. The fossil specimen on which the Hydrotherosaurus figure was based was 25 feet long.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: The Cretaceous diorama. This is not a particularly good photograph, however, it is one of few that clearly shows the Pteranodon (top right of the photo). Top right: Huff's mosasaur. Middle left: The left side of the diorama, featuring the hadrosaurid and mosasaur. Middle right: The right side of the diorama with the plesiosaur. Bottom: A series of photographs show the process of creating the Cretaceous diorama's hadrosaurid. From the left, (a best guess is that) Huff paints a release agent on his original clay sculpture so that it will separate easily from a plaster mold; when the mold has hardened, the mold is carefully split and the clay sculpture is exposed and removed; a wire armature is positioned within the mold to provide support and added strength; the two halves of the mold are rejoined, clamped together, and plaster is poured into it from the bottom; and after some touching up, finishing and applying paint, the figure is ready to be placed in the diorama. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

The Eocene diorama imagines a southern California mountain forest and flood plain. The area residents include two Teleodus, three Amynodontopsis, Triplopus and two Hyaenodon. The restorations were based on fossils from the Sespe Formation, Ventura County, California.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top: The Eocene diorama. In this photograph the two Hyaenodon are visible in the lower left corner. Middle left: A sharper photograph of the diorama from a slightly different angle. Only the head of one Hyaenodon is visible here. Middle right: A closeup of the two battling Teleodus. Note the reflections of a ladder and other equipment in the glass; this photograph was probably taken just prior to the opening of the fair. Bottom: From left are the two creodont Hyaenodon, two rhino-relative Amynodontopsis, the rhino-like perissodactyl Triplopus (running), and two of the brontothere Teleodus. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

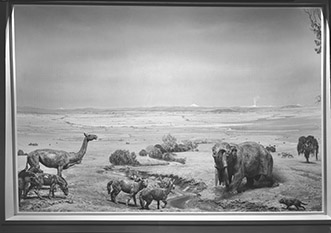

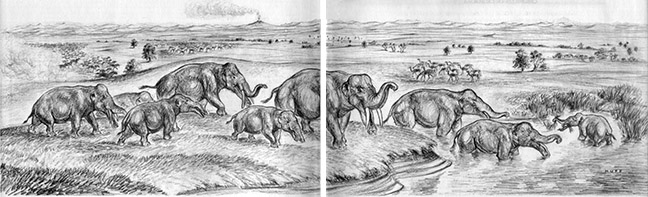

The Miocene (considered Pliocene at the time of the GGIE) diorama pictures a stream coursing through dry grasslands in the Mt. Diablo area. Drawn to the water supply are Procamelus, Gomphotherium (originally called Trilophodon), three Hipparion, two Pliohippus, three Merycodus and Osteoborus. The restorations are based on fossils from the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry, Contra Costa County, California.

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Top left: The Miocene diorama. Top right: A closer look at the Pliohippus and Merycodus figures. Middle: From left are two of the early horse Hipparion, the North American camel Procamelus, and two of another early horse Pliohippus. Bottom: From left are two pronghorn relatives Merycodus, the elephant relative Gomphotherium, and the "bone-crushing" dog Osteoborus. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

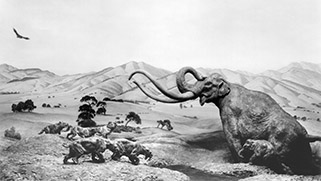

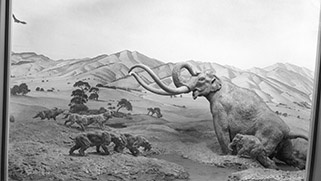

The Rancho La Brea asphalt pits of southern California are shown in the Pleistocene diorama, featuring two Columbian Mammoths, three Canis dirus (dire wolves) and two Smilodon.

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Top left and right: The Pleistocene diorama. The photograph on the right, though skewed, shows more detail. Middle: Four views of the adult mammoth. The view at far left shows a step in the casting process. Bottom: From left are three of the "dire wolves" Canis dirus, the two saber-toothed Smilodon and the baby mammoth. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

The life-size heads

Huff's life-size heads of Miocene and Pleistocene mammals were:1

Paramylodon, a giant ground sloth, based on a skull from the Pleistocene Rancho La Brea asphalt pits, Los Angeles County, California.

The three-toed Miocene horse Hipparion, from a skull found at the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry, Contra Costa County, California.

The giant bison Bison latifrons, based on a skull found near Mount Shasta, California.2

The deer-like Synthetoceras, based on a skull from the Miocene of Donley County, Texas. Named and described by Ruben Stirton in 1932.3

Smilodon californicus, based on a skull from the Pleistocene Rancho La Brea asphalt pits, Los Angeles County, California.

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Left: A clipping from a 1938 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle that includes a photograph of Huff with his head of Smilodon californicus. HFA. Center: The September 6, 1938, issue of the Oakland Tribune featured Huff and the head of Synthetoceras. HFA. Right: The September 2, 1950, issue of the Berkeley Daily Gazette featured the Synthetoceras head years later when the Department of Paleontology was still based in the Hearst Mining Building. HFA.

Click on any image to see a larger and complete version. Top: From left are Huff's life-size head reconstruction of the giant ground sloth Paramylodon and three photographs of the giant Bison latifrons. Bottom: From left are three photographs featuring Huff's Smilodon californicus and one showing four of his original five reconstructions. In the third image from the left, UCMP's Samuel P. Welles is shown with two visitors (and the Smilodon head) on the crowded mezzanine of the Hearst Memorial Mining Building. The photo on the far right was taken in 1957 in Bacon Hall. Except for the bottom right photo, all are from the Large Format Negative and Print Collections, UA; that bottom right photo from Joan Perusse, "The History of the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry" (Spring 1957, Paleo 170 paper), Joseph T. Gregory Papers, Records Room, UA.

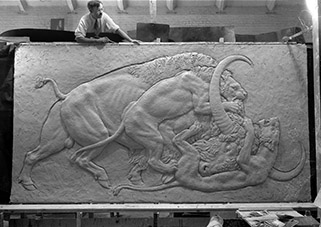

The bas-relief

What may have been Huff's most eye-catching piece was his bas-relief of two American lions attacking a giant bison. Its position in relation to the rest of the exhibit is unclear, although, a University news release stated that "the panel will be placed by itself in a space specially prepared opposite the University's main display in the Hall of Science." This is a very vague description but it sounds as if the bas-relief was placed either just inside or outside the east entrance to the Hall of Science.1

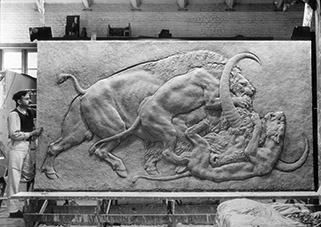

Click on these thumbnails to see enlarged versions. Top left: Huff with what may be his original clay version of the lions attacking a giant bison. Top right: Huff with the finished plaster bas-relief. Bottom: The cover of a 1971 report about the museum's first 50 years sports an illustration that clearly shows the bas-relief in the lobby beyond the ground-floor south entrance of the Earth Sciences Building. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA; report cover from the UA.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: Huff and an assistant prepare the plaster mold of the bas-relief. Right: Huff works on his gomphothere sculpture for the Miocene diorama with the bas-relief in the background. Both photos HFA, on indefinite loan to the Peña Adobe's Mowers-Goheen Museum.

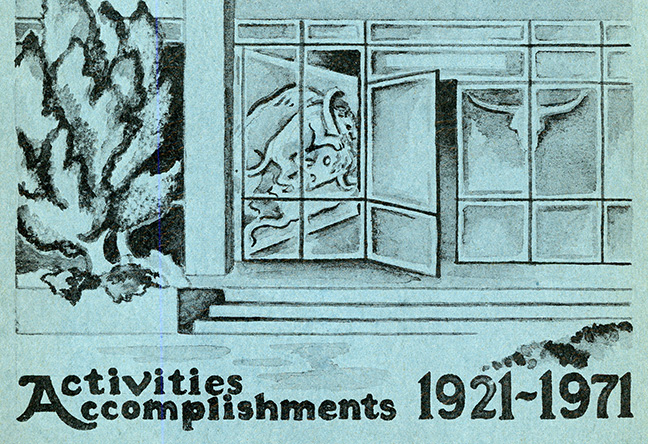

The other paleontology exhibits

Huff designed a large branching tree of life charting "The Rise of the Vertebrates" (see image below). Ward's Natural Science Establishment of Rochester, New York, and grad student Natasha Smith provided the models used on the tree, but many of the vertebrates pictured in the display—some of which were represented in the dioramas—were drawn by Huff.1

Click on the image to see a larger version. "The Rise of the Vertebrates" display with some of Huff's illustrations barely visible along the right branches of the tree. From University of California Committee on Cooperation with the Golden Gate International Exposition, Science in the Service of Man: Exhibits in the Basic Sciences. Hall of Science, Golden Gate International Exposition 1939-40 (San Francisco, 1940).

A smaller display called "The Evolutionary History of the Horse" compared the skulls, limbs, and teeth of five prehistoric horses, but contained none of Huff's artwork.2

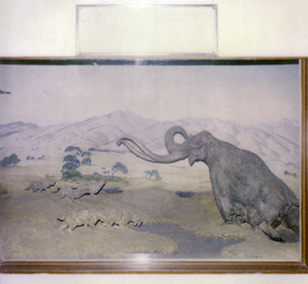

Though not listed in the Science in the Service of Man exhibits guide, GGIE photographs in the collections of The Bancroft Library3 suggest that the paleontology exhibit had two other small displays. One was a display of skulls from the Rancho La Brea asphalt pits which included some photographs taken during early UCMP excavations there. The second display highlighted fossils recovered from the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry and other Contra Costa County localities. It featured a panoramic drawing by Huff of Miocene life in the vicinity of Mt. Diablo, with gomphotheres dominating the scene. This same drawing may have been used later for the frontispiece of Charles Camp's book, Earth Song: A Prelude to History (see "Earth Song" on page 5).4

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top: A Miocene landscape in the region of Mt. Diablo, Contra Costa County, California, dominated by a herd of gomphotheres. From Charles L. Camp, Earth Song: A Prologue to History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), frontispiece. Bottom: From left, two American Lions attacking a giant bison, two Smilodon and the head of Synthetoceras. In typical Huff fashion, he did not date these fine drawings but they probably were done at the time of the GGIE. Bottom three drawings from AHR.

Other Huff accomplishments at the GGIE

On the opening night of the GGIE, February 18, 1939, Huff was one of six judges of a beauty contest, naming Audrey Anderson of Oakland "Queen of the World's Fair Premiere."1

Both Huff and Strong exhibited artwork in the GGIE's California Building. Strong had a painting and Huff had a bronze head of his Chief Solano, probably the same head that is now on display in the Mowers-Goheen Museum in Peña Adobe Regional Park.2

One week after the beauty contest, Huff was initiated into the Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus on Treasure Island.3 Read more about Huff's life as a Clamper on page 3.

1940 additions

Originally intended to last one year, the GGIE was still in the red at the time of its October closing so it was decided to reopen it for a few more months in 1940. The second incarnation of the fair debuted on May 25, 1940, with a number of new and/or different displays, activities and pavilions. For year two of the Exposition, Huff added some new pieces to the paleontology exhibit.1 There were about 20 plaster or ceramic bas-reliefs of prehistoric animals and possibly a sixth life-size head restoration to join Bison latifrons and the others; this new one was of Pliohippus, another early horse (see "The fate of the life-size heads" below). Huff also created a new display featuring invertebrate fossils of Mt. Diablo. This may have replaced either the La Brea or Black Hawk Ranch display.2

Click on these thumbnails to see enlargements. Eighteen of Huff's 20 or so plaques that he made for the second year of the GGIE. Top: From left are plaques of the Jurassic bird Archaeopteryx, the armored dinosaur Stegosaurus, the Cretaceous ceratopsid Triceratops, the elasmosaurid plesiosaur Hydrotherosaurus, the large Eocene flightless bird Gastornis (Diatryma), the Devonian placoderm Dinichthys, an early hominid, the Eocene "dawn horse" Eohippus, and an early primate. Bottom: From left are the Jurassic sauropod Brontosaurus, the Devonian sarcopterygian Eusthenopteron, the horse relative Hipparion, an even older horse relative Miohippus, the flying reptile Pteranodon, the Permian tetrapod Seymouria, Tyrannosaurus rex, the Eocene mammal Uintatherium, and a dicynodont. Photographs from the HFA and/or Large Format Negative Collection, UA.

What became of Huff's GGIE sculptures?

Huff's GGIE exhibits were meant to be temporary so all of his sculptures were made of plaster. When this investigation into the life of Huff began, only two of his GGIE sculptures were known to still exist: (1) the large bas-relief of the lions attacking the bison—this piece is in UCMP's Regatta storage facility in Richmond—and (2) one of the five life-size heads, the Synthetoceras, that was restored in 2012 and that still resides in a back room of the museum. Nobody really knew what had become of the six dioramas and the other four life-size heads; one assumed that they had fallen apart or had been destroyed. Who expected these temporary plaster sculptures to survive 70+ years?

The fate of the dioramas

Documents and photographs in the UCMP Archives indicate that the six dioramas were brought back to Berkeley following the GGIE and installed in Bacon Hall; they remained there through at least 1957.1 The Bison latifrons head was transferred to the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco in 1961 or 1962 but whether other heads as well as the dioramas went with it is unknown.2 The Cal Academy has been unable to shed any light on the matter. At any rate, two of the dioramas—the Permian and Pleistocene—somehow found their way to San Francisco's Randall Museum at 199 Museum Way; that's where UCMP's Director for Collections and Research Mark Goodwin found them in the early 1980s. Mark was there to collect a whale skeleton that the Randall was returning and, since they were planning a major exhibit overhaul, they asked him if he wanted the dioramas back too. He agreed to take them and they went into storage at the museum's Clark-Kerr facility until around 1997 when Diane Blades, representing the San Joaquin Valley Paleontology Foundation, took them south, ostensibly for the new Fossil Discovery Center in Chowchilla. Unfortuntely, the dioramas were not adequately prepared for the long drive, and by the time they reached Chowchilla, several of Huff's plaster figures had suffered damage. No longer fit for display, the dioramas went into storage. There they sat until 2012 when the dioramas were rediscovered in the Madera County equipment yards by Lori Pond, then president of the San Joaquin Valley Paleontology Foundation. Written across the top of each diorama were instructions to throw them out. Lori couldn't bear to see them destroyed so she had the dioramas moved to her home's garage where they filled two bays (each diorama is the size of a small car).3 She hoped to find a new home for the dioramas as well as funding for their restoration. Mark Humpal—art dealer, historian and Ray Strong biographer—and I contacted museums as well as Huff and Strong family members in an attempt to generate some interest in saving the dioramas, but unfortunately, no one came forward. Lori Pond lost a battle with cancer in October of 2016 and, as I understand it, her heirs disposed of the dioramas. But Mark Humpal and I were fortunate enough to see and photograph the two dioramas in Lori's garage when we paid her a visit in 2014. Considering that the dioramas were temporary and were intended for the single-year run of the GGIE, it's really quite amazing that they survived for another 77 years! What became of the Triassic, Cretaceous, Eocene and Miocene dioramas remains a mystery.

Click on either image to see a larger version. The Permian (left) and Pleistocene dioramas installed at the Randall Museum. Polaroids taken by Mark Goodwin.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: The Permian diorama in Lori Pond's garage. A bit of the Pleistocene diorama is visible at left. Top right: A look at the diorama from the left side reveals the disintegrated Dimetrodon figure to the right of the three Edaphosaurus. Bottom: The Edaphosaurus against Ray Strong's nearly pristine background. Photos by David Smith, 2014.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: The Dimetrodon and Diplocaulus. The foregrounds and figures were covered in so much accumulated dirt and dust that it was difficult to see what color they were. Top right: The upper right corner of the diorama reveals the plaster shell construction. Bottom left: The two Eryops were still in decent condition despite the blanket of dirt and dust. Bottom center: A closer look at the Edaphosaurus group. Bottom right: The Diplocaulus. Photos by David Smith, 2014.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: The Pleistocene diorama in Lori Pond's garage. A portion of the Permian diorama is visible at right. Top right: The head of the adult mammoth. One tusk has broken away from the armature. Middle: An overall view of the Pleistocene diorama. Both Smilodon figures were damaged with one broken off of its armature. Bottom left: The three Canis dirus were undamaged. Bottom center: Some of the legs on the still-standing Smilodon were shattered. Bottom right: The baby mammoth was in good condition. Photos by David Smith, 2014.

The fate of the life-size heads

When I began researching the life of William Gordon Huff, I knew of only one surviving head: that of Synthetoceras, which had floated around the museum and its storage facilities for many years before being restored in early 2012. I assumed that all the other heads had been lost and/or destroyed. But in late 2012, news came of two more of the original heads and a previously unknown one (Pliohippus). At a conference on the east coast, Senior Museum Scientist Pat Holroyd was talking with Sally Shelton, Associate Director of the Museum of Geology and Paleontology Research Laboratory, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, about collections issues when Pat happened to mention Huff's name. Sally revealed that in moving to a new building, their museum discovered three sculpted heads by Huff for which they'd love to find a new home. Pat relayed this information to Mark Goodwin. Mark, who has a strong interest in UCMP's history, said that he would gladly take the heads and pay for the shipping costs.1 It took a while, but in June 2014, a 450-pound crate containing the heads of Paramylodon, Hipparion and Pliohippus arrived at the museum. Unfortunately, all three heads look pretty bad for having been painted once or twice over the years; some work would be needed to restore them to their original appearance. All three are now stored out at UCMP's Regatta facility.

Click on these thumbnails to see enlarged versions. Top: The three rediscovered Huff heads at the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology prior to being shipped to Berkeley. At left are two views of the slightly damaged Paramylodon head. On the right are the Hipparion (left) and Pliohippus heads. All photos by Sally Shelton. Bottom left: Me with the three heads after uncrating them in UCMP's prep lab. Photo by Mark Goodwin. Bottom right: The three heads are back in Berkeley, 75 years after Huff created them. Photo by David Smith.

How did the heads end up in South Dakota? Both Professor Emeritus Bill Clemens and Sally Shelton believe that Reid Macdonald may have been responsible. Reid got his Ph.D. at Berkeley in 1949 and took a job as curator at the Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, that same year. But he left that position in 1957 and in the UCMP Archives, there is a photo, circa 1957, that shows the heads still in Berkeley.2 Reid retired to Rapid City in 1980 and lived out the last 24 years of his life there. It's still possible that he was behind the transfer of the heads to South Dakota but as yet, there is no hard evidence.

Nevertheless, now only the heads of Bison latifrons and Smilodon are unaccounted for. As noted above, the bison head was sent to the California Academy of Sciences around 1962, during the tenure of Robert Cunningham Miller's directorship. Since the bison and Smilodon are arguably the finest heads in the bunch, I hold out hope that they still exist somewhere. Perhaps someday, they too will return home to UCMP.

The fate of the bas-relief

The bas-relief of the two lions attacking the giant bison has remained safe with the museum ever since the GGIE. When UCMP moved from the Hearst Memorial Mining Building to its new space in the Earth Sciences Building (now McCone Hall) in 1960, the bas-relief was mounted on a wall just inside the ground-floor south entrance and it remained there for over 30 years. It was removed around 1995 when the museum relocated to its current space in the Valley Life Sciences Building. The bas-relief was crated and put into storage. It too resides at the museum's Regatta storage facility but no doubt it will reemerge one day.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: The crated bas-relief being loaded into a truck for its journey to the Regatta storage facility in Richmond. Photo by Mark Goodwin. Right: The crate currently is stored behind other oversize displays that once graced the walls of the Earth Sciences Building (McCone Hall). Photo by David Smith.

On the next page we'll look at Huff's historical plaques and his relationship with E Clampus Vitus.