A UCMP special exhibit

The Art of Sculptor William Gordon Huff

Part V: Projects Through the 1970s

Open the Sources page for Parts V and VI in a new window.

Art production, despite a day job

Since Huff now had a regular job at the ANAS and a steady income, he could stop looking for art commissions, however, his art production did not seem to slow down. Jobs came his way from UCMP, E Clampus Vitus (see page 3), his collaborator and friend Ray Strong, and elsewhere.

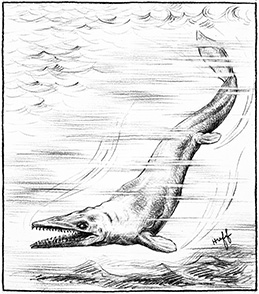

Just prior to his going to work at the ANAS, Charles Camp asked Huff to draw a reconstruction of the Upper Cretaceous mosasaur Kolposaurus, whose bones had been discovered in Fresno County. Huff's drawing appeared on the frontispiece of Camp's 1942 paper on California mosasaurs.1 A year later, Huff did a similar job for Sam Welles. He drew a reconstruction of an elasmosaurid plesiosaur for the frontispiece of Welles' monograph on the subject.2

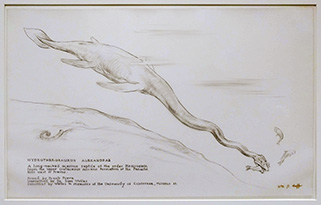

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: The drawing of Kolposaurus (now called Plotosaurus) that Huff drew for Camp. From the UCMP Large Format Negative Collection, 0901-1000 box; sleeve UCMP 0921, #650. Right: Huff's drawing of the elasmosaurid plesiosaur Hydrotherosaurus that he did for Sam Welles. AHR.

Huff may have had another job with UCMP in 1943, suggested by a single letter in the UCMP Archives. Director Charles Camp wrote to Annie Alexander on April 8, saying "I am making arrangements to get Bill Huff to do some work in setting up exhibits for the elementary classes."3 What those exhibits were and whether they were actually prepared is unknown.

Mt. Diablo Museum

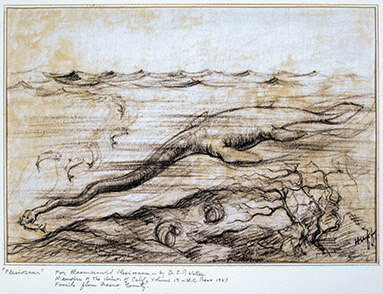

Between February 1948 and March 1949, Huff and Ray Strong made three attempts to offer their expertise in designing new exhibits for the Mt. Diablo Museum at the top of the mountain (3,849 feet) in Contra Costa County. They had a clear vision of what the exhibits should depict and Huff spent quite a bit of time researching and collecting resource materials. The two worked up an outline describing what they envisioned; they had significant support from local citizens and UC Berkeley professors, but nevertheless, their proposal was shot down each time and whatever plan was ultimately made for the Mt. Diablo Museum, it did not benefit from the input of Huff and Strong.1

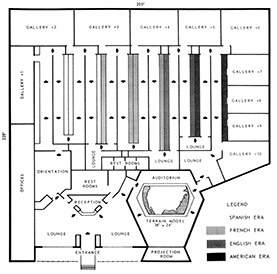

Click on either image to see a larger version. Huff and Strong went so far as to draw up floor plans for the displays they envisioned for the Mt. Diablo Museum. HFA.

Camp's Earth Song

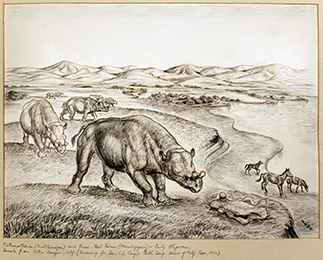

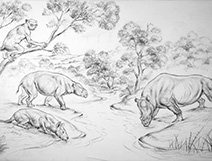

In 1952 Charles Camp published his book Earth Song: A Prologue to History which featured more than 30 original drawings by Huff.1 Strangely, no correspondence relating to this project has been found in either the Huff or UCMP Archives. The whereabouts of only three of Huff's original drawings for the book are known. One is displayed at the Mowers-Goheen Museum at Peña Adobe Regional Park and Huff's daughter has another. A third was held by Ray Strong's estate but is now in David Smith's possession. The fate of the rest is unknown.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: Huff's drawing of titanotheres and early horses for Charles Camp's Earth Song. AHR. Right: Another drawing for Earth Song, this one of the head of Bison latifrons, the giant bison Huff had sculpted for the GGIE about 13 years earlier. Originally from the RSFP, now with David Smith.

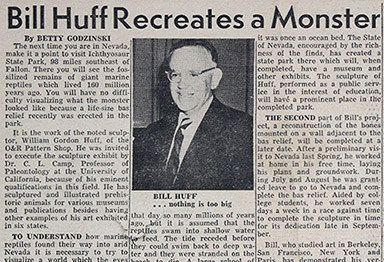

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park

The bones of ichthyosaurs had been discovered in West Union Canyon in the Shoshone Mountains of Nevada as early as 1928 but it wasn't until 1953 that someone from UCMP went out to take a look at them. That someone was Charles Camp. In one afternoon it became obvious to Camp that a major excavation was warranted. During the summers of 1954 through 1957, Camp, with crews of workers made up of family members, friends, visitors and other folk from UCMP, discovered the bones of some 37 individuals in ten quarries along a one-mile stretch of the canyon.

Through the urgings of Camp and others, the Nevada legislature designated the area Ichthyosaur Paleontological State Monument in 1955. Two years later it achieved State Park status, and, after the acquisition of the nearby ghost town of Berlin, it became Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park in 1970. Read more about Berlin-Ichthyosaur elsewhere on the UCMP website.

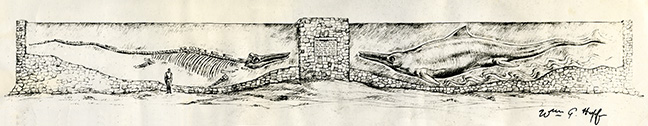

The first shelter to protect the main quarry would not be built until 1966, but in 1957 Camp recruited Huff to create two life-size bas-reliefs of Shonisaurus, the ichthyosaur genus found in the canyon. These would adorn a wall to be built against a bank just south of the quarry. One bas-relief would be of the skeleton and the other would be a reconstruction.1

Camp brought Huff up to the main quarry on May 27, 1957, so that he could prepare a cost estimate. In his field notes for this day, Camp wrote:

Bill figured on his job of reconstructing full size ichthy on retaining wall this year if okay on his contract is granted.

Bill estimate cost of reconstructions two walls—each 70 feet long—with one ichthy in full relief—body reconstruction and one showing skeleton at 11,000. This would take the next two summers.

Estimates costs for next two summers:

Restoration: $11,000; Water system: $3,000; Bulldozing: $1,000; Preparation of specimens: $4,000; Transportation and food: $3,000; Concrete pouring for walls: $1,200; Museum construction: $24,000; Salary of custodian: $5,800.

TOTAL: $53,000

We worked up a schedule of costs to be submitted to Gov. Russell tomorrow. Also dimensions of ichthy:

Overall length: 60 feet; Head: 10 feet; Neck: 2 feet; Body: 16 feet; Tail: 32 feet; Paddles: 52+ (about 60 inches) each2

Click on the image to see a larger version. Huff's original plan for two full-sized ichthyosaur bas-reliefs at Berlin-Ichthyosaur. HFA.

When Huff learned that the State was only able to scrape together funds for one bas-relief, he chose to scrap the skeleton and do the reconstruction. By June 7, Huff had provided Camp with sketches of his proposed reconstruction as well as bids for the materials he would need. A bulldozer was brought in to cut into the bank south of the quarry to prepare for the massive bas-relief. On July 8 Huff, with his wife Doris and son Colin, came up to make final site preparations and begin construction of the concrete forms. On the 16th, lumber and plaster were delivered and Camp made this entry in his field notes:

This evening Kent's truck came with supplies for Bill's wall. … Arrived here much overloaded and top heavy. Bill got in the cab with the driver and when truck reached level spot at top of quarry hill it eased over on its side giving Bill quite a squeeze. The driver landed on top of him as well as everything loose in the cab—including a heavy box of tools.

We worked till after dark getting out the sacks of plaster (90 sacks), damaged and undamaged.

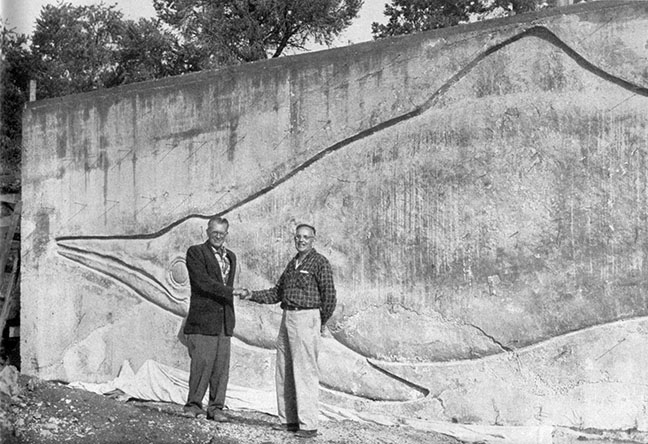

Huff actually broke a rib in the accident. The following morning, the remaining plaster and lumber was removed from the tipped truck. Between the 19th and August 29, the concrete forms were built and Huff prepared the mold for the ichthyosaur bas-relief. Huff, Doris and Colin returned home on August 30th and were not present when the 50 cubic yards of cement were poured into the forms on September 11. Between the 22nd and 25th, all the lumber was removed from the finished wall. Huff returned on the 28th to finish cleaning up the wall and prepare for the "unveiling" on the 29th. Camp described the event:

Whole big crowd … went up and built benches, hauled away debris and put parachute cloth up for "veil" ….

Rain commenced at 11 am and came down intermittently with thunder and hail until nearly 3 when 100 or more people had appeared.

Dedicating included introduction of Bill Huff by me—his fine speech—a closing paragraph or two when the monster was unveiled by pulling a cord and Mrs. Margaret Wheat christened him Shoshonisaurus [sic] with an old bottle filled with Pacific Ocean water. All then fled from the impending rain and had a dinner of two turkeys provided by Lt. Commander and Margaret Grant who also brought champagne partly provided by personnel of the Air Base. Drank, toasted and made merry until late.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: Wooden framing supports Huff's original sculpted ichthyosaur relief as volunteers apply plaster to create a mold. Courtesy of the Nevada Department of Transportation. Right: A color photograph taken about the same time as the one above appeared in a 1958 issue of Nevada Highways and Parks. From "Life-sized model built at Ichthyosaur State Park," Nevada Highways and Parks (1958), volume 2, p. 31.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Volunteers apply plaster to Huff's relief to create a mold for the concrete. Courtesy of the Nevada Department of Transportation. Top right: Huff's completed ichthyosaur relief and the new, open-ended A-frame shelter built to protect the main quarry. Courtesy of the Nevada Department of Transportation. Bottom left: An article appearing in the November 8, 1957, issue of The Carrier, a Navy publication, about Huff's work at Berlin-Ichthyosaur. AHR. Bottom right: An October 6, 1957, San Francisco Chronicle article about the unveiling of the ichthyosaur relief. HFA.

Click on the image to see a larger version. Charles Camp (left) congratulates Huff on a job well done at the dedication ceremony. From "Life-sized model built at Ichthyosaur State Park," Nevada Highways and Parks (1958), volume 2, p. 31.

Huff had the ichthyosaur painted a solid black, but at some point, somebody decided to paint a white iris for the eye and Huff was angered by what he viewed as vandalism. To this day, the white iris remains.

Click on the image to see a larger version. A 2008 photograph of Huff's ichthyosaur relief. Note the white iris on the ichthyosaur. Courtesy of Charles Marshall, UCMP.

As noted on page 3, after two earlier attempts (in 1961 and 1966), Huff was finally able to mount his plaque celebrating Charles Camp at the entrance to the shelter covering Berlin-Ichthyosaur's main quarry in 1973.

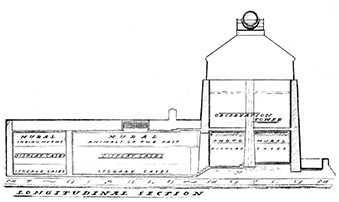

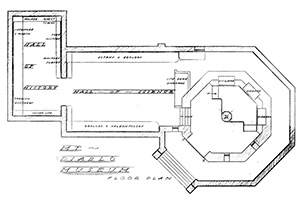

A museum for Berlin-Ichthyosaur

In the cost estimates given earlier, note that there was a figure given for "Museum construction." Camp and Huff, and later, Ray Strong, were determined to have a museum or educational displays built near the ichthyosaur quarry. They were aware that the State of Nevada did not have the funds to construct anything too grandiose so they explored the possibility of obtaining grants and other cost-saving measures. They began the effort in earnest in the fall of 1961.

Strong probably put in the most effort towards the museum project. With Camp's input, he created a scale model of his vision for the museum, he convinced architects at Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin West in Scottsdale, Arizona, to supply preliminary drawings, used those drawings to get cost estimates for a Fleischmann Foundation grant application, and met with architectural students at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo about drawing the final plans and/or making scale models of the structure.1

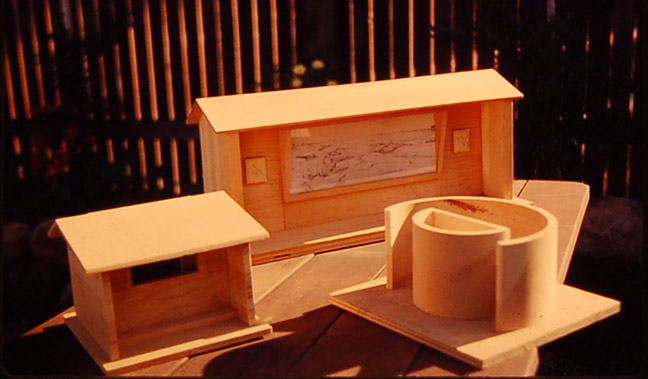

The Fleischmann Foundation application probably was submitted in late 1962, but the estimate for the museum came in at a whopping $195,000 (about $1,632,000 in 2019 dollars) and the grant was denied.2 But Huff and Strong kept at it. In an attempt to keep costs at a minimum, Huff thought that they could, instead of pushing for a museum, do something smaller, such as educational kiosks. In August of 1963, Huff wrote to Strong:

I have constructed three more models, variations of the one you have, but more complete. One design in particular I like very much—better than the first one. The principle is the same, but it is better in that you have to look at the diorama through an elongated window from the outside. The window is somewhat on the narrow side (height) to maintain semi-darkness in the chamber between the viewer and the diorama opening. The reasons for liking this one are: (1) Simple to contract; (2) No maintenance problem; (3) Vandalism proof (almost); (4) Attendant not needed to stand around. … This is a natural for us, Ray. We have casts for the animals. Without too much work we could develop the whole thing ourselves including the full size structure. … We could make them for state parks and National Parks and other areas ad infinitum. … One of the models is two feet long. It shows what can be done in the way of presenting an outdoor mural. The structure, entirely different from the diorama type, would be very practical to construct full size. It, too, could be used in parks. I have demonstrated the idea completely including the glass which is pitched at a seven degree angle.3

Huff's three informational kiosk designs for Berlin-Ichthyosaur. The two-foot-long model that Huff mentions above is the rear one. HFA.

Huff's quote provides a good example of the level of enthusiasm generated in both Huff and Strong when a project captured their imagination, and especially if they stood to profit from it. Two months later, Huff wrote to Strong again:

I still think something could be provided in the way of a museum through the Fleishman [sic] Foundation—nothing elaborate, mind you, but something simple in the way of exhibits. As you know, the state architect's office produced drawings for a museum building. It was designed to be constructed in native stone. The cost, as such buildings go, would not be much, and most of the money—if the Fleishman [sic] Foundation could be prevailed on to pay for such a project—could be spent on exhibits, as per our plan. … Instead of submitting a bid for $195,000 for just the building, as was done before, maybe they would go for say, $60,000 which would include everything …. I bet the building could be erected for not more than $10,000 using free native stone—that would leave $50,000 for our work. Anyway, Ray, I think it is a good idea.4

Sadly, the plan fizzled and nothing came of the Berlin-Ichthyosaur museum. Huff tried to revive Camp and Strong's interest in October, 1965, but that was the last gasp—neither a museum nor a kiosk ever materialized.5

Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History

V.L. VanderHoof, the paleontology graduate student who had helped Huff and Strong during the GGIE, had gone on to become Director of the SBMNH in early 1959. In May of that year he wrote to Huff:

We may get a 350,000 grant for a new hall of bird and mammal habitat groups and I have asked for about 20,000 for professional assistance from a sculptor and painter. Now guess who are the two (or maybe one) I have in mind? The question is, what would you and Ray Strong need in the way of a fee and could you get away? This could lead to a permanent post, espec. for you, with no forced retirement on account of age.1

Huff was content with his position at the Alameda Naval Air Station and chose to pass on the offer, however, Strong jumped at it and ended up moving to Santa Barbara and doing a considerable amount of diorama work for the SBMNH.

Hearst Museum of Anthropology exhibit

From a couple of references in the Ray Strong Family Papers, Huff and Strong apparently prepared a small exhibit for the Hearst Museum of Anthropology in 1960 that involved one or more mannikins. In a letter from Huff to Strong dated September 6, 1961, Huff wrote, in regard to their idea for a museum at Berlin-Ichthyosaur, "Maybe we can dress a couple of mannikins a la Kroeber Hall [home of the Hearst Museum of Anthropology] exhibit of last year." The only other reference to this job was a penciled note on a copy of a letter that Strong had written December 10, 1960. Strong, in musing about his income for the year, mentioned "the $500 for U.C. Anthropology."1

Zion and Petrified Forest National Parks

In April 1960, the Western Museum Laboratory of the National Park Service contacted Charles Camp, seeking recommendations for artists to work on some paleontological exhibits for Zion National Park in Utah. Unsurprisingly, Camp directed the Lab to Huff and Strong. Strong was asked to provide two paintings and the background for a diorama; Huff was recruited to do a single figure for the latter, a scene of a Jurassic landscape featuring the small, bipedal dinosaur, Segisaurus halli.1

Huff consulted with Camp and Don Savage, another Berkeley vertebrate paleontologist, on the appearance of the animals to be depicted in both the diorama and the paintings.2 He then provided Strong with sketches of the animals; these were traced onto panels, then painted.3 For Huff's Segisaurus figure, Camp was the perfect person to have as an advisor because it was Camp who originally described Segisaurus halli in 1936.4 Huff's completed figure was about nine inches high and 13 inches long.5 The finished exhibits were probably in place by the end of Spring 1961.

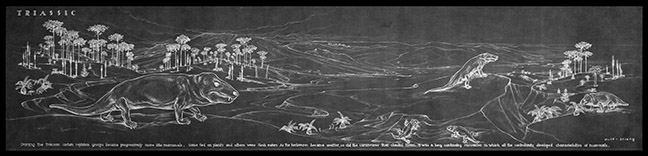

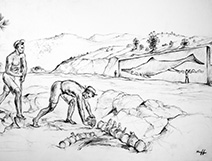

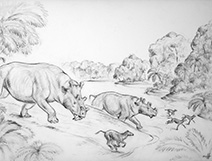

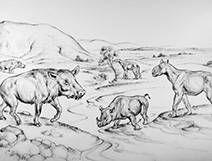

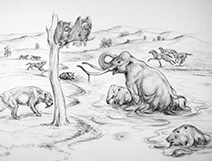

About the time work was wrapping up on the Zion project, the Western Museum Laboratory asked Ray Strong if he could do a mural for the Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona.6 Ray's finished 4x16-foot mural, which he had intended to render in paint, was left as a white chalk drawing on a dark gray background; it depicted a Triassic landscape, populated with the plants and animals whose fossils are found in the Park. These included Placerias, a somewhat hippo-like dicynodont; a metoposaur; and Desmatosuchus, an armored aetosaur. Once again, Camp was called upon as a consultant and Huff provided Ray with sketches of the animals.7 Mural installation took place in July, 1961.8

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: The finished paintings and diorama that Huff and Strong prepared for Zion National Park. Huff's Segisaurus can be seen in the center diorama. Image from the Harpers Ferry National Park collections and shared with me by Mark Humpal, March 31, 2016. Top right: Strong's chalk mural at Petrified Forest National Park as it looked in 2015. The left side featured the dicynodont Placerias. Photo by Matthew Smith, Petrified Forest National Park, and shared with me by Mark Humpal, February 16, 2017. Bottom left: The right half of the mural features the phytosaur Machaeroprosopus (left) and the aetosaur Episcoposaurus, known today as Desmatosuchus. Provenance same as the previous photo. Bottom right: Huff's preliminary sketch for the aetosaur. It's possible that this sketch could date to 1941 when Huff and Strong were working on dioramas for the Palo Alto Junior Museum because the aetosaur in the Triassic diorama is identical (see the photo under the PAJM subhead on page 4). AHR.

Hallway exhibits for UCMP, Earth Sciences Building

In late 1961 the University of California's Department of Paleontology contacted Huff and Ray Strong regarding the creation of hallway exhibits for the Earth Sciences Building (now McCone Hall). The Department and UCMP had just moved into this new building from their cramped quarters in the Hearst Memorial Mining Building and they wanted to install a series of displays for the public. At this time, Huff was still employed at the Alameda Naval Air Station full time so Ruben Stirton sent an appeal to UC Berkeley Chancellor Ed Strong (Ray's brother) asking the Chancellor to contact the ANAS on the Department's behalf about "securing the loan of Mr. Huff's services" for four to five months. Stirton believed that a request coming from the Chancellor would carry more weight. Apparently it did and the request was granted because Huff worked on the hallway exhibits from October of 1962 through early 1963. Stirton described the exhibits: "These will consist of restorations (drawings and paintings) of the Black Hawk Ranch and other faunas—vertebrate and invertebrate. Other items to be designed and executed will be of a phylogenetic and stratigraphic nature."1 Huff prepared exhibits on invertebrates under the direction of Bill Berry. He also worked with Zach Arnold and Robert Kleinpell on foraminifera and on vertebrates with Stirton.2 Huff was well paid for his time. Tax forms in the Huff Family Archives show that he earned $5,500 from the University in 1963; adjusted for inflation, that's about $45,430 in 2019 dollars.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Cover of the Guide to the Museum of Paleontology exhibits, circa 1964. UA. Top right: A portion of Ray Strong's painting of the Grand Canyon that was located on the second floor of the Earth Sciences Building (ESB), opposite the elevators. It is doubtful that the painting survived UCMP's move to the Valley Life Sciences Building in 1995. From the collection of Tim Strong, shared with me by Mark Humpal, March 15, 2016. Bottom: This Miocene scene by Huff, now reframed and mounted in an office just off UCMP's reception area in the Valley Life Sciences Building, was once mounted on the first floor, east corridor, west wall of the ESB. The animals shown represent those whose fossils have been found in the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry on the southwest slope of Mt. Diablo. UA; photo by David Smith (visible in the reflection).

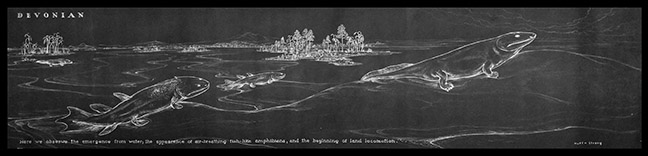

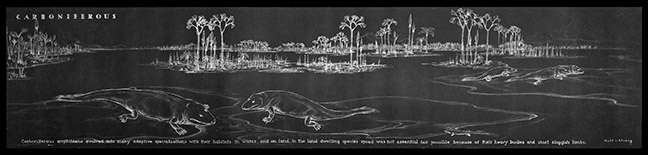

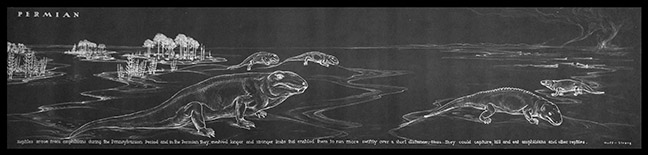

Click on any image to see a larger version. In the UCMP Archives are rolled, actual-size, "negatives" of several Huff-Strong drawings created for the Earth Sciences Building exhibits. These four scenes illustrated terrestrial adaptation of vertebrates from the Devonian to the Triassic. All these were displayed on the ground floor, west corridor. All from the UA; photos by David Smith.

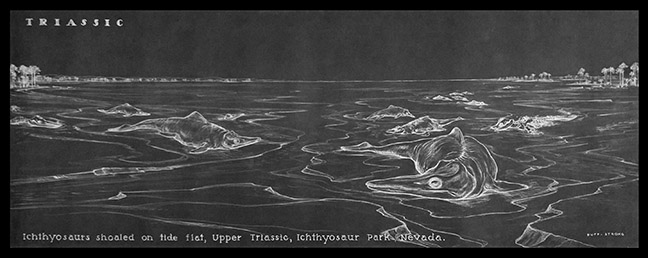

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top: This image of beached ichthyosaurs accompanied a wall-mounted skeleton of the ichthyosaur Cymbospondylus. It was displayed on the ground floor, west corridor of ESB. Bottom left: Huff's drawing of Hydrotherosaurus was placed near the wall-mounted skeleton of the elasmosaurid plesiosaur in the ESB's ground floor foyer. This drawing and that of the beached ichthyosaurs, like the Miocene panorama pictured earlier, have been reframed and adorn the walls of an office off of UCMP's reception area in the Valley Life Sciences Building. Apparently, all the Huff-Strong drawings for the ESB exhibits were executed in something like dark green pencil. Bottom right: Other drawings from the ESB exhibits are in storage out at the museum's Richmond storage facility. All from the UA; photos by David Smith.

Project 400/Hillendale Museum

The last Huff-Strong collaborative project took the longest—about eight years—and in the end, may have had the least to show for it in terms of art productivity. There was also an event that would put a strain on the two artists' friendship.

In 1960 or 1961, Strong encountered Ernest N. May, a wealthy former Du Pont employee residing in Wilmington, Delaware, who, like Strong, was interested in art and how it could be used to educate. May was also an American history and geography buff. With Strong's encouragement, May set out to build a museum whose purpose was "to present to the visitor a chronological exposition of the discovery, the exploration and the exploitation of North America, particularly of the United States, with special emphasis on geography and its influences."1

The museum project was called Project 400 for the 400-year period between 1490 and 1890 on which May chose to focus. Financing for the project came almost entirely from May himself through his Charitable Research Foundation. With a very small staff and the input of advisors, such as Strong, May put together a list of the events that he'd like to see reproduced in dioramas or paintings.

Strong was one of several artists recruited to provide displays for the museum. He was assigned four dioramas and four paintings, six of them dealing with the adventures of Lewis and Clark. Huff was subcontracted to sculpt the figures for Strong's dioramas. Strong put in a huge amount of time and effort researching the scenes he was responsible for depicting, traveling to the sites visited by Lewis and Clark so that he could produce accurate sketches and producing full-size mockups of the dioramas using plywood and masonite. Huff did his own share of research into the clothing his figures would be wearing; he modeled several figures for the four dioramas.2

Huff would sculpt the four-inch-high figures in plaster and ship them down to Strong in Santa Barbara, where the painter was then living. In June of 1967, Huff's involvement with the project nearly came to an end when he received a very atypical letter from Strong in which the latter complained that Huff's figures were "stiff, impersonal, without feeling for the specific time and place of their involvement with it." Strong went on to say that "to get excitement out of a work it has to be put in. … You have not [put it in] and all your highly professional sense of proportion and finished detail does not compensate for this lack." Huff took these comments from his friend surprisingly well (on the surface), saying "I am not hurt, Ray, as you suggested I might be, with your brutal frankness. … Because of a feeling of warm friendship, and for old times sake I thought I could be of service—but since that service has been recorded on the negative side there is nothing for me to do but to cancel myself out." Almost immediately, Strong must have seen the error of his ways and urged Huff to stay on the job; in a letter written just six days after his previous one, Huff said that he was back working on the figures and it was clear from his tone that he was happy about it.3

Construction of the museum in Mendenhall, Pennsylvania, was completed in 1966 and it opened to the public three years later. Despite all the preliminary work put in by Strong and Huff, they ended up producing only one diorama (using just two of Huff's figures) and one painting (by Strong) for the museum, principally due to Ernest May's inability to make timely decisions, his troubles with many of the artists involved, and concerns over the amount of money being spent. Huff and Strong's involvement in Project 400 came to an end in mid-1968 making it their final collaboration.4

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: A page from a Hillendale Museum brochure. RSFP. Top right: The Hillendale Museum's floor plan. RSFP. Bottom left: The one diorama completed by Strong and Huff was of Lewis and Clark's first view of the Great Falls of the Missouri. From the collection of Tim Strong. Bottom right: This small figure in the Huff Family Archives is probably one that went unused. Photo by David Smith.

Associated Students of the University of California

Huff and Strong were to have an interesting relationship with the Associated Students of the University of California (ASUC) student organization in the early 1960s. There were three projects in which the pair were involved.

Art Activities Center

In typical Ray Strong fashion, the painter recognized an opportunity when he learned about the construction of a new student union complex on the UC Berkeley campus. He wasted no time—this was late 1958 or early 1959—in contacting the architects to provide input on an arts center planned for the complex;1 funding for the center was from the Levi Strauss Foundation.

The student union was completed in March 19612 and when the Art Activities Center opened, it was a "space … for the University Family: students, employees, faculty, graduates and their wives." Frequenters of the Center could work in photography, painting, drawing, sculpture, enameling, glass, and other crafts. Advice and guidance in these various skills was provided by local specialists, including Ray Strong (in painting) "when up on leave from his Santa Barbara work." Huff was billed as a "guest artist" providing assistance with sculpture.3 Strong actually became the director of the Center but stepped down July 1 for fear of ruffling too many feathers within the administration and art department; he also had other obligations in Santa Barbara and found the Center to be more about crafts and not so much about painting.4 Huff probably made just a handful of appearances at the Center. One interesting note regarding the Center is that it is one of the few spaces in the student union complex whose appearance and function have remained relatively unchanged since the building was completed more than 60 years ago.

Click on the image to see both pages of the flier. A flier describing the Art Activities Center's mission, activities and resident experts was printed up. From the collection of Tim Strong.

Benito Juàrez monument

At the same time as Strong and Huff were involved in the Art Activities Center, the pair were also in communication with Forrest Tregea, Executive Director of the ASUC, hoping to obtain student support for the creation of a large monument honoring Mexican President Benito Juàrez (1806-1872). Although Huff would be sculpting the monument, Strong shared his friend's ideals and lobbied hard on his behalf. They produced panels explaining the importance of the project and Huff provided a scale model. Strong liked to think big and imagined that the ASUC Executive Committee would bring in a Mexican university and make it a bicultural project. A September 1961 letter from Strong to Huff was the last to mention the Juàrez project.1 It's entirely possible that the student body supported the project, however, a lack of funding was probably what killed it.

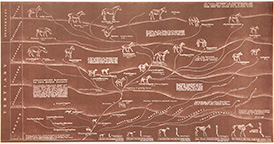

Evolution of the Horse poster

No doubt taking advantage of Ruben Stirton's expertise, Huff developed a poster charting the "Evolutionary Radiation of the Horse Family" in the spring of 1961. This seems to have been a pure Huff piece, but both he and Strong recognized that the ASUC could be a great way to distribute the poster and other quality educational materials; they had a couple thousand posters of the horse panel printed up and they presented them to Forrest Tregea, the ASUC's Executive Director, simply asking to be compensated for the printing costs. The ASUC could sell them for whatever they could get and keep the profits. This seems to have been done as early as July 1961. The pair did a second printing four years later with the intention that the ASUC would again be the recipients. Whether or not the poster helped inspire UCMP to hire Huff and Strong to work on its Earth Science Building hallway exhibits is unknown.1

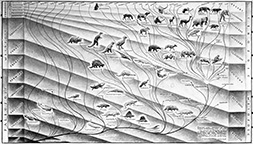

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Huff's sketch for the proposed Benito Juàrez monument. AHR. Center: Huff's Evolution of the Horse poster. AHR. Right: This Huff poster depicting the path of vertebrate evolution does not appear to have been produced for the ESB hallway exhibits but it is placed here because of its similarity to the horse poster. Just when and why it was made is unknown; it's possible that it was produced for the second year of the GGIE since all the animals pictured in the poster just happen to be sculptures and/or reliefs that Huff made for the fair (see page 2). Large Format Print Collection, box containing prints 0417-0705, no. 0472, UA.

California Academy of Sciences

In spring 1962 Huff was engaged by Robert Cunningham Miller, Director of the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, to sculpt a life-size model of a rhinoceros. A rhino skin was then stretched over the model for one of the Academy's African dioramas.1 Perhaps this job for Miller was somehow related to the relocation of Huff's life-size head of Bison latifrons (and perhaps the GGIE dioramas?) to the Cal Academy, for that too took place in 1962.2 Miller also may have asked Huff about working on a foraminifera display for the Academy because Huff had written to UCMP micropaleontologist Zach Arnold asking if he'd be interested in collaborating on such an exhibit. Arnold had to decline citing too many other commitments and it seems that Huff withdrew from the project as well.3

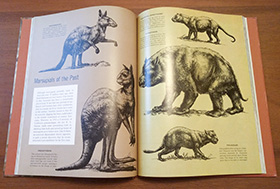

Time-Life illustrations

Ruben Stirton, who had been making important discoveries of marsupial mammal fossils in Australia, wanted Ray Strong to paint reconstructions of some of these animals for a Time-Life volume about the country. Stirton was planning another trip to Australia in 1962 and Strong was hoping to accompany him. To finance the trip, Strong applied for a Guggenheim fellowship, but unfortunately, he did not receive it. Without the funding, Strong had to decline the offer to do Stirton's reconstructions.1 Not too surprisingly, Huff was then recruited to draw the reconstructions;2 another artist did the final artwork that appeared in the 1964 Time-Life book entitled The Land and Wildlife of Australia, but Huff was credited for the original drawings on which they were based.3 It was probably around this time that Huff drew his whimsical reconstruction of Stirton as a kangaroo-like marsupial (see image below).

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Cover of the Time-Life volume on Australia. Center: A two-page spread in the Time-Life volume with reproductions of extinct Australian marsupials based on Huff's sketches. The book is in David Smith's collection. Right: Huff's whimsical cartoon of Ruben Stirton as a Procoptodon-like marsupial. UA.

Stories of Fossils

In 1964, Charles Camp received a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant as a principal investigator in the University of California Elementary School Science Project to produce a book of stories and classroom activities concerning fossils for (tentatively) grades 2 to 6. Huff submitted a proposal to the Project offering to provide illustrations for the book. The proposal was accepted and Huff produced 34 drawings at $50 each for the book ($1,700 or, more than $13,860 in 2019 dollars), which was called Stories of Fossils. Preliminary versions of the book were printed by the University of California Printing Department in 1966, however, there is no evidence that it reached the publication and general distribution stages.1 All 34 of Huff's original drawings for the book are in the UCMP Archives.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Of the 37 stories in Camp's book, Huff did illustrations for 34. These are nine of his finer drawings. All from the UA; photos by Dave Strauss. Top left: This figure accompanied story #2, "Hunting Fossils: Where Do You Look?" Top center: This illustration, featuring Huff's own ichthyosaur relief from Berlin-Ichthyosaur, appeared with story #24, "Oldtime Sea Serpents." Top right: This drawing, that included the early bird Archaeopteryx and a pterodactyl, was from story #28, "Which Came First—the Hen or the Egg." Middle left: Dinotheres and early horses populate this Eocene Wyoming scene for story #19, "Old Jim Bridger and the Fossil Horses." Middle center: The dicynodont Placerias looks on from a safe distance while two phytosaurs battle it out in this drawing accompanying story #30, "Battle of the Dragons." Middle right: Huff referred back to his own 1939 GGIE sculptures when drawing the non-arboreal animals for story #18, "A Boy Works His Way up into Paleontology." Bottom left: Miocene mammals found at Agate Springs, Nebraska, are featured in this drawing for story #14, "The 'Stone Bones' of Nebraska." Bottom center: Story #9's illustration depicts the asphalt pits of Rancho La Brea, "The Tar Pits at Rancho La Brea in Los Angeles." Bottom right: Desmostylans appear in the illustration for story #17, "The Seashore Beachcombing Monsters of California and Japan."

Oakland Museum of California

In 1964, Huff was contacted to gauge his interest in working on exhibits (with Ray Strong) at the Oakland Museum of California, then in the planning stages. Three existing Oakland museums—the Oakland Public Museum, the Oakland Art Gallery and the Snow Museum of Natural History—would be combining their collections in a new building.1 Although Huff was the initial contact, Strong did most of the wheeling and dealing with museum representatives. There were several meetings and a lot of discussion, but in the end, Strong ended up with a contract to paint a background for a condor exhibit; there is no evidence to suggest that Huff's involvement ever progressed beyond the meeting stage.2

Huff and the Vietnam War

Although Huff rarely "bared his soul" in his correspondence, he did not hold back in making clear his feelings about the Vietnam War. Despite his early involvement with the ROTC and his job at the Alameda Naval Air Station, Huff had become a pacifist, vehemently opposed to war and the use of nuclear weapons. In a response to the escalation of the war in Vietnam, Huff complained to Ray Strong in an October 24, 1965, letter: "Because of the world situation—our stupid foreign policy etc. I feel like fighting. I can't fight our pip-squeak bastards in Washington so the only other way to give vent to my pent up emotions is to dive into something creative."1

Three years later, just a few months before his retirement from the Alameda Naval Air Station, Huff wrote to Ray Strong to express his continuing outrage over the Vietnam War, with some choice words for President Lyndon Johnson as well. He was so angry that he changed political parties (he was a lifelong Democrat but opted to join the Peace and Freedom Party). Huff wrote "For the sake of my blood pressure I try not to dwell too much on what is happening today, but I find myself brooding about it much of the time anyway. Our moral values are so twisted and distorted that even Mussolini would be shocked at the way our political leaders are behaving." Huff went on to unleash a string of foul epithets against Johnson but apologized to Strong ("Please forgive my gutter parlance").2

Huff and his wife Doris had subscribed to the Oakland Tribune for many years but because the paper backed the Vietnam War, they cancelled their subscription. "Our prejudice against the paper was so deep rooted we haven't recovered. … I know it is bad to nurse such a prejudice, but for the next three thousand years this country will not be forgiven by the world for our killing and bombing those poor little people who did absolutely nothing against us to invite such suffering at our hands—let alone what our bastard leaders did to destroy fifty five thousand of our own boys; and the Oakland Tribune applauded all the while these atrocities were being perpetrated."3

Huff's anger over the Vietnam War did not help his already high blood pressure. In the same letter as the above quote, Huff wrote "If I bought a Tribune [Oakland Tribune] … I would have to burn it immediately—if I saw it lying around my blood pressure would rise, and I am taking dyazide capsules already to keep it down."

He did channel some of his anger into his art, creating at least three large pastel drawings with an anti-war theme. A letter Huff wrote to Strong dated September 15, 1971, would suggest that he began these in the early 1970s. In it he says "Have done only one more large pastel since I last saw you—that made the third big one. I have a number of sketches for more large ones …."4

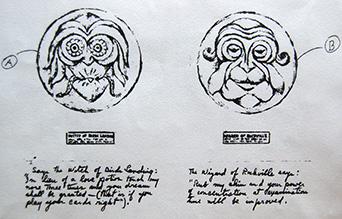

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Although not overtly anti-war, this pastel is still disturbing. Clear plastic has been stretched over the frame to prevent smudging. Center: Huff explains this pastel on the back of the piece: "'The Spirit of Evil' mesmerizes the military; 'The Eye of Human Decency' contemplates the bloody hands of the military; 'The Monkey' is safe with a snake in the same jungle; 'The Hands of Brotherhood' invoke Eternal Peace for the innocents slain by the military." Right: In this pastel, Huff makes his feelings about war quite plain. All from the HFA; photos by David Smith.

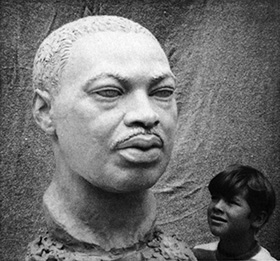

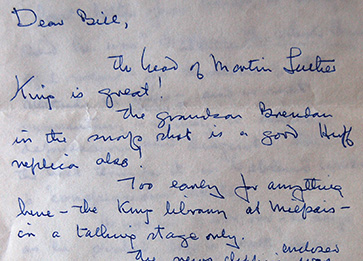

Martin Luther King Jr. head

Less than two months after Huff's February 1968 letter to Strong (the one in which he used "gutter parlance"), Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. would be assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. Huff was deeply affected by the tragedy and wasted little time in sculpting a twice life-size head of the man. He had finished the head by the middle of June and sent a photograph of it to Ray Strong saying "Different ones have been by to see the model and they seem to be impressed. The only question is money—a hurdle that shouldn't be too great to jump. Am still thinking in terms of the colossal. … Have more work to do on it before I make the cast. Am planning on sending a set of pictures of all angles of the head to Mrs. Martin Luther King for criticism before I take this step. … I am certain that something will come of the project, but just what remains to be seen."1 In August, Huff wrote to Strong again: "Yesterday a committee of four from the Black community of Oakland came out to see the Martin Luther King head. They all said they liked it very much and want to push for the colossal one—to be erected in Regional Park possibly. It will be interesting to see if anything comes of it. I have long since learned not to get my hopes up too high. If it materializes fine and if it doesn't so what—just another dream down the drain."2

Left: Huff's bust of Martin Luther King Jr. HFA. Click on the image to see a larger version. Right: A portion of Ray Strong's letter, circa June 1968, written in response to the letter and photograph that Huff had sent him. The letter identifies the young man in the photograph. HFA.

As it turned out, the head was never cast in bronze and placed in a public location. According to Huff's son Tim, the sculptor was disappointed by the inaction of the interested parties and ended up destroying his model, however, he kept the mold. In an effort to see his father's dream realized, Tim Huff has been putting out feelers over the past few years to see if he can drum up new interest in getting the head cast in bronze.3

The Peña Adobe period

School teacher, photographer, and history buff Robert Wilson Allen (1925-2016) moved to Vacaville in 1962 and quickly became interested in Solano County history. This interest became something of an obsession; Allen founded and became president of the Vacaville Heritage Council and was an active member in the Solano County Historical Society, the Peña Adobe Historical Society, and the Vacaville Museum. Like Huff, Allen was also a member of the Yerba Buena Chapter #1 of E Clampus Vitus and it was probably through this organization that the two met and became friends.1

Allen's concern for the preservation of the Peña Adobe and/or his role as head of a city project "that researched and placed bronze plaques on buildings in the Vacaville Downtown Historical District" may have had something to do with Huff being lured back to Solano County.2 You may recall that Huff was already somewhat knowledgeable with the history of Solano County because of the research he'd done for his Chief Solano statue in 1933 (see page 1).

It was probably Allen who introduced Huff to Rodney Rulofson (1901-1975) a few years prior to Huff's 1968 retirement from the Alameda Naval Air Station. Rulofson was curator of the Peña Adobe and the associated Mowers-Goheen Museum in south Vacaville. Rulofson and Huff struck up a friendship, and as a retiree, Huff found himself with more time on his hands. He began to spend a good deal of that time at the adobe, helping to restore the building and neighboring grounds.3

Huff would produce six plaques for the Peña Adobe Regional Park area, all previously described on page 3.

Following Huff's death in December 1993, his friends from E Clampus Vitus and those he made during his time spent at Peña Adobe gathered at the Adobe in April 1994 to celebrate the many contributions of the sculptor and his wife Doris.

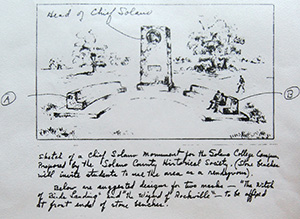

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Huff pitched an idea to create a second Chief Solano monument for the Solano Community College campus to Peña Adobe curator Rodney Rulofson around 1973, give or take a couple years. This is his sketch for the monument. HFA. Top right: Curving benches would flank Huff's Chief Solano monument and Huff envisioned a small mask adorning the far ends of each. These are rough sketches of the proposed masks. The monument did not materialize. HFA. Bottom left: Bill and Doris chat with Big Bear, a local Native American, at a Peña Adobe event that was probably held in the mid- to late-1970s. HFA. Bottom center: About four months after Huff's death, a "jubilant memorial" was held at Peña Adobe in April 1994 to celebrate Bill and Doris. HFA. Bottom right: A closeup of the sign on the tree describes Huff as "Clampus Sculptor, Extraordinaire; Perpetual Clampsculptor; Clampatriarch of the Grand Council." HFA.

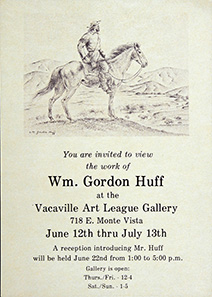

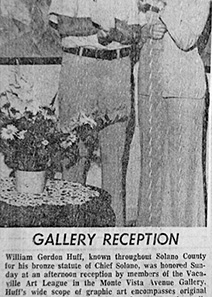

Huff art exhibition

Probably through the urgings of his many Vacaville and Peña Adobe friends, Huff mounted a solo exhibition of his artwork at the Vacaville Art League Gallery in July 1975.1 Huff had entered pieces in Bay Area art exhibitions in the '30s but it had probably been a good 35 years since the last time he did so.2 The show featured a number of Huff's sketches and drawings, including many of his abstract pastels.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: An invitation to Huff's Vacaville Art League Gallery show in 1975. AHR. Center: An article from the Vacaville Reporter about Huff's Vacaville show. In the photograph, Huff and his son Colin carry a large cubist pastel of battling elephants; this is one of three known cubist pastel drawings that Huff based on earlier drawings (see the charcoal sketch of battling elephants on the next page). HFA. Right: Two newspaper clippings about Huff's show, one from the Vallejo Times-Herald and one from the Sacramento Bee. HFA.

About two months after the close of the gallery show, Huff learned of Rodney Rulofson's death. Huff was honored to create a plaque of his good friend; it was dedicated by the "Indian community of Northern California" on March 28, 1976, and is located north of the Mowers-Goheen Museum, just yards from Huff's plaque marking the Native Americans' common grave (see page 3, 1976 entry).

Following the dedication of the plaque, Huff's visits to Vacaville became less frequent. He'd now lost his good friend at the adobe, and one year before, his longtime UCMP friend and mentor, Charles Camp. But Ray Strong was still around; Strong would outlive Huff by 13 years, passing away in 2006 at the age of 101.

The final page of this feature takes a look at Huff's personal art projects and a miscellany of molds, medallions and other artwork.