A UCMP special exhibit

The Art of Sculptor William Gordon Huff

Part IV: Post-GGIE and Alameda Naval Air Station

Open the Sources page for Part IV in a new window.

The years 1939 through 1941 would be extremely busy for Huff. Even while working on the monumental sculptures and Paleontology Department exhibit for the GGIE, he continued to pursue other jobs and he had an ally in UCMP's Ruben Stirton, whose research interests concerned fossil mammals. Stirton served as an advisor to Huff and Strong on the dioramas that featured mammals and in the process, became a promoter for the team. In March 1939 he wrote a lengthy letter to Arthur Sterry Coggeshall, then Director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, singing the pair's praises.

My object in directing this to your attention is to seek additional opportunities for Huff and Strong. I do it, not necessarily with the idea of supplying these men with work, but because I fully believe they have a new and most interesting way in putting Paleontology across to the public. … Having just finished the Fair displays, these men are now available.1

In February 1940, knowing that the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Kansas was looking for a new preparator, Stirton suggested Huff:

I should like to recommend William Gordon Huff. … he is a sculptor, and an artist of unusual ability. He can make beautiful casts, and his restoration of missing parts is particularly good. As a preparator, strictu sensu, he has had little experience, since we kept him on more difficult work; but I do not question his ability to do it. … In any event, he is tops and everyone is enthusiastic about his work. Huff is a young man, but is married and has a family. Furthermore, he is very likable and it is a pleasure to work with him.2

Of course, Huff himself was actively seeking new projects. In August of 1939 Huff wrote to the University of Texas Bureau of Economic Geology in Austin, Texas, asking whether they could use someone to model restorations of fossil animals and it's very possible that he sent similar letters to a number of universities and museums at that time. Austin's response was negative and it's unlikely that inquiries of this type generated much interest.3

In September of 1940, Chester Stock, a paleontologist who had left Berkeley in 1926 for the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, wrote to Huff describing a plan by Los Angeles County "to develop Rancho La Brea as a park showing unique scientific features. There are planned among the latter a number of life-size restorations of the characteristic Ice Age mammals found fossil in the tar pits." Stock went on to say that it is "my desire in communicating with you to determine whether you might be available … and to obtain such information as I might concerning costs. Could you give me an estimate of what the cost would be to make a restoration such as I have indicated above, or of some of the other animal types?" This project really sounds like something Huff would have been eager to do, however, nothing seems to have come from Stock's inquiry; perhaps the county was unable to come up with the funding. Of course, today there are life-size restorations of mammoths at La Brea; it would be interesting to know whether Huff was the first to be approached about the job.4

None of the potential jobs described above materialized, but perhaps it was just as well since Huff found himself with more than enough work to keep him busy.

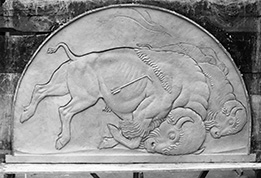

Bison Hunt

In 1939 or early 1940 Huff learned of a nationwide competition sponsored by the Federal Works Agency's Section of Fine Arts. It was seeking designs for a sculptural piece to decorate the post office in Bryan, Texas (see a photo of the post office on flickr). Huff's design, a 4.75 x 7.5-foot semicircular bas relief depicting stampeding bison pierced by Indian arrows, won the competition and he worked on the piece during the latter half of 1940. "The sculptured panel 'Bison Hunt' has now been installed over the door to the Postmaster's office in the lobby" read an FWA press release, circa early 1941.1 Today, the old post office now houses federal offices (Bryan Federal Building, 26th and Parker Streets) but Huff's relief is still there.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: An early version of Huff's Bison Hunt bas-relief shows a minimal amount of detail. HFA. Center: The finished piece shows a good deal more texture added to both the bison and the background.2 From a print originally in the RSFP but now in the UA. Right: A newspaper article about the mounting of Huff's Bison Hunt in the Bryan post office. From the February 18, 1941, issue of The Eagle (Bryan, TX).

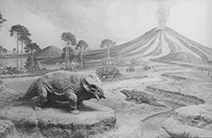

The horse film

Just as the GGIE was reopening for its second year, Huff became involved in a University of California Visual Instruction Department (Extension Division) project: a film on the history of the horse. In a May 1940 letter to a lawyer friend in Los Angeles, Ruben Stirton wrote "the University extension division has underway a motion picture on the horse and they have spoken to Mr. Huff about a sequence of restorations illustrating the geological history of the family."1 Ray Strong was also recruited and the "dioramic duo" set about producing six dioramas showing the evolution of the horse, with Huff doing the horse sculptures and Strong painting the backgrounds. The pair worked on these dioramas during the latter half of 1940 and early 1941.

In a June 16, 1941, letter to Sam Welles, Charles Camp wrote "Robertson2 [Sophus Robertson] is finishing up the horse movie and Bill Huff, Hugo [Goeritz], Van [V.L. VanderHoof] and I went down Ingram Creek with Robertson the other day and dug up a fake horse skull for the benefit of the camera." A couple of 35 mm Kodachrome slides found in the Charles Camp collection, UCMP Archives, actually illustrate this activity (see photos below).

Click on either image to see a larger version. Left: Huff (left) and Camp expose the "planted" horse skull for the film. Right: Hugo Goeriz (left), V.L. VanderHoof and Huff after putting a plaster jacket on the skull. Both images from the Charles Camp 35mm slide collection, UA.

The completed film, The History of the Horse in North America, was released in October 1942. An article in that month's edition of The Educational Screen, a "Magazine Devoted to Audio-Visual Aids in education," reads:

Horse Film Completed by University Extension

Another research film has been completed by the Visual Instruction Department of the Extension Division of the University of California. The History of the Horse in North America, a 4-reel color motion picture, begins with archeological research and reconstructed prehistoric scenes, when the horse was no larger than a fox terrier, and follows through with a magnificent series showing the horse of today. … Organizations, schools and others throughout the State may use the film by contacting the department of Visual Instruction, 301 California Hall, University of California, Berkeley.

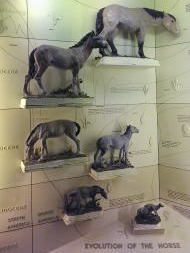

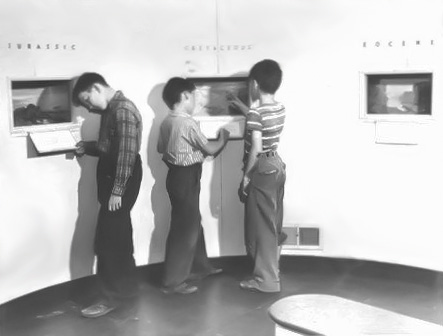

Based on photos in the UCMP Archives (see photos below), it appears that the dioramas were temporary in nature. After the film was completed the dioramas were probably destroyed, although Huff's horse sculptures were salvaged. At the request of V.L. VanderHoof—Director of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, former UC Berkeley grad student and one of Huff's helpers with the GGIE paleontology exhibits—Huff made a second set of them (from his molds) late in 1960.3 As of 2016 they were still on display at SBMNH.4 It is remarkable that the original set has survived as well. It probably sat in UCMP's teaching collection for over 50 years until 1991 when the sculptures were hauled out and included in a display on evolution at The Museums at Blackhawk in Danville (see photos below). UCMP had several exhibits there through 1997. Following the close of the exhibit, the horse sculptures apparently were given to a local high school; the school later donated them to the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County in Chowchilla, CA. The horses have had some repairs and a fresh coat of paint, but they are still on display there.5

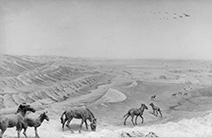

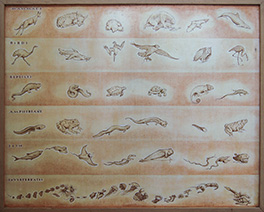

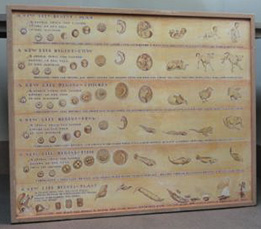

Click on any image to see a larger version. Photographs of five of the six dioramas exist; why there is no photograph of the Eocene diorama featuring Hyracotherium is unknown. Top left: The Miohippus (Late Eocene to Oligocene) diorama. Top center: The Parahippus (Early Miocene) diorama. Top right: The Merychippus (Middle Miocene) diorama. Middle left: The Pliohippus (Late Miocene) diorama. Middle center: The Equus (Pleistocene) diorama. Middle right: This color image of the Equus diorama shows that it was meant to be a winter scene (or perhaps it was meant to suggest an Ice Age). Bottom: From left to right are closeups of Huff's Hyracotherium, Miohippus, Parahippus, Merychippus, Pliohippus and Equus sculptures. All images from the Large Format Negative Collection, UA, with two exceptions: The color Equus image is from Charles Camp's collection of 35mm slides, UA; and Hyracotherium, HFA.

Top left: The Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History horse evolution display. Top right: The lower half of the SBMNH display. The three larger sculptures are Huff's but there are two Hyracotherium; the one in front is probably the one in the closeup photo above but nothing is known about the other. Bottom left: The Equus sculpture is similar to, but is not one of Huff's; what happened to his Equus is unknown. Bottom right: Huff's Pliohippus in the SBMNH display. All courtesy of Terri Sheridan, SBMNH.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Five out of the six original Huff horse sculptures made it into this display on horse evolution at The Museums at Blackhawk. Top right: A bit of Huff's Pliohippus and Equus at The Museums at Blackhawk. These two photographs courtesy of The Museums at Blackhawk, photos by Francis Sakamoto. Middle left: The sculptures eventually found their way to the Fossil Discovery Center of Madera County in Chowchilla, CA. This is Huff's Hyracotherium with a new coat of paint. Middle center: Huff's Miohippus but here they've labeled it as Mesohippus. Middle right: Huff's Merychippus. Bottom left: Huff's Pliohippus. Bottom right: Huff's Equus. All Chowchilla photographs by David Smith.

At the top of this page we saw two examples of how Ruben Stirton went out of his way to create opportunities for Huff. A 1946 letter from Stirton to Huff suggests that they considered contacting Bay Meadows, a horse racing track in San Mateo, to create horse dioramas for that facility.6

Stirton saw to it that Huff's horse sculptures were featured in a Bay Area television program called Science in Action, broadcast on KGO-TV January 15, 1952. Stirton was the guest scientist for an episode called The Horse. One week later, the life-size Bison latifrons head that Huff made for the GGIE made an appearance on an episode about the buffalo called Vanishing Herds.7

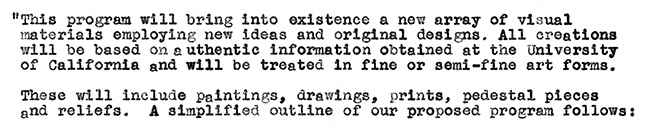

Visual education

Huff and Strong really bonded during the GGIE and felt that as a team they could produce marketable visuals for a variety of purposes. Both men clearly saw that their talents would be beneficial to schools as educational aids, so in the spring of 1941 they wrote a draft of a letter advertising their availability, qualifications and references to be sent to school districts throughout northern California.1 When the finished letter went out is unknown, but what is known is that Huff and Strong received no responses.2

Never ones to give up easily, the pair added Ruben Stirton to their team later in the year. The three men worked out a proposed program, but unfortunately, they never got the chance to see what might become of this new marketing attempt because the United States was now embroiled in a world war. As they noted in the program, "This outline was completed just before the outbreak of the war and recently has been set aside for the duration."3 There is no evidence to suggest that Huff, Strong and Stirton pursued their visual education idea following the war.

Click on the image to see the complete document. A portion of the document outlining Huff and Strong's visual education program. Undated document in the Ruben A. Stirton Correspondence, 1924-1945, box 1, folder 34, Stirton "U" Correspondence, 1930-1944, UA.

Stirton was to die unexpectedly at a southern California conference in 1966. Huff made a plaque relief to honor his longtime friend but what became of it is unknown; perhaps it was given to Stirton's family. Huff sent a photo of the relief along with news of Stirton's death to Ray Strong. In his response, dated June 23, 1966, Ray wrote "Thanks for the … sad news of Stirt's death … I liked him very much. … The plaque relief is fine Bill and meant a lot to me to know you have accomplished this in his honor as man, friend and scientist."4

The Palo Alto Junior Museum

In 1941, Huff and Strong learned of the completion of a new building for the Palo Alto Junior Museum (PAJM) that had a focus on art and nature. The artists felt that there was a need for exhibits on evolution, so they put together a proposal for a new science wing, described the exhibits they envisioned, and even built a crude model of their plan for the wing's design. Armed with all this, they made a presentation to the Palo Alto Community Center, the organization behind the museum, and were successful in selling the idea.1 To what degree Huff and Strong's original plan was adhered to—such as in the design of the science wing—is unclear.

A grant proposal was submitted to the Columbia Foundation, the funds were secured, the science wing was built, and Huff and Strong completed all their exhibits within a year (the science wing opened in 1943).

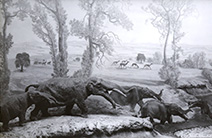

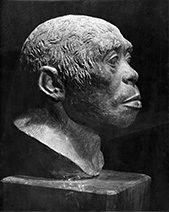

In a book published in 1947 entitled Life Through the Ages: A Visual Introduction to the Story of Change in Living Things,2 the science wing exibits of Huff and Strong are described in text and photographs. Much like those that they made for the GGIE, the two artists created a series of "life through time" dioramas, but on a child-size scale; based on photographs of their displays, apparently some time periods were represented by two-dimensional drawings/paintings (see photos below). They also made a number of wall-mounted panels—Strong painted the backgrounds and Huff added most of the figures and text. In addition, Huff sculpted three busts of early humans for the science wing.

This photograph, courtesy of the Palo Alto Historical Association, shows the small size of the PAJM dioramas.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Huff-Strong paintings and dioramas at the PAJM and two of Huff's preliminary sketches. Top row: From the left are the Devonian painting, Permian diorama and Carboniferous painting. Middle row: From the left are the Triassic diorama, Jurassic diorama and Huff's preliminary sketch for the Cretaceous diorama. Bottom row: From the left are the Cretaceous, Eocene and Oligocene dioramas. PAJM glass slides originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA; the slides were by Gabriel Moulin Studios of San Francisco. The two preliminary drawings are from AHR.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Huff's sketch of the deer-like Syndyoceras for the PAJM's Miocene diorama (not pictured). AHR. Top center: A sketch by Huff of three gomphotheres that Strong must have flipped horizontally and used as a guide when painting the background for the Pliocene diorama. HFA. Top right: The Pliocene (now considered Miocene) diorama. PAJM glass slide originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA; slide by Gabriel Moulin Studios of San Francisco. Bottom left: Huff's sketch of an adult and baby mammoth for the PAJM Pleistocene diorama (not pictured). AHR. Bottom center: Huff's drawing of early hominids living in caves. PAJM glass slide originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA; slide by Gabriel Moulin Studios of San Francisco. Bottom right: A diorama showing how early humans followed mammoths across the Bering Land Bridge to North America. PAJM glass slide originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA; slide by Gabriel Moulin Studios of San Francisco.

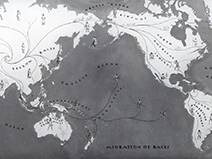

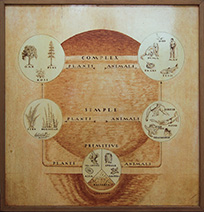

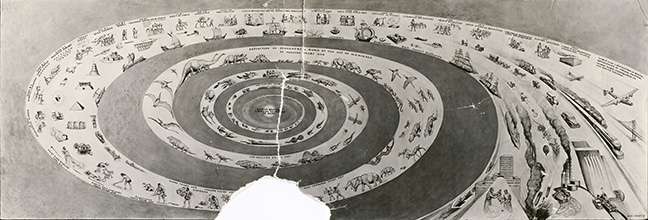

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: A preliminary sketch for a a drawing of early hunters. Top center: The finished early hunters drawing. Top right: Huff's drawing of lake dwellers.Bottom left: Huff's drawing of the beginnings of agriculture and the domestication of animals. Bottom center: A Huff and Strong panel showing the migration of races around the globe. Bottom right: A panel that Huff drew for the PAJM showing life through time. This is actually an image of a poster based on the panel that was printed (and probably sold) by Stanford University in 1943. PAJM bison hunt, lake dweller, early agriculture and migration glass slide images originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA; slides by Gabriel Moulin Studios of San Francisco. The preliminary sketch and Life Through the Ages chart from AHR.

Huff and Strong's exhibits remained in place for about 20 years. In 1965, the PAJM was ready to make way for all new exhibits. Wanting to be involved in the planning process, Ray Strong again offered his and Huff's services, but this time they were turned down. The PAJM gave them the opportunity to reclaim their material; Strong reappropriated several of the wall-mounted panels3 but Huff was willing to let it all go—he salvaged nothing from the museum. The dioramas and Huff's busts presumably went into storage. Strong had moved to Santa Barbara in 1960 but made the trip north to collect the panels. At least two of them were reexhibited at the SBMNH and as of 2011 they were still in storage at the museum.4 Following Strong's death, his heirs returned two panels to Huff's eldest son, Tim. Other panels found homes elsewhere.5

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Huff's bust of Peking Man that he made for the PAJM. He also made busts of a Cro-Magnon and Neanderthal. Photo originally from Ethel Strong Adams, now in the UA. Top center: A panel comparing simple and complex forms of life. HFA. Top right: Huff's panel showing representatives of various groups of animals. HFA. Bottom row: All three of these panels were primarily Strong's work, however, Huff added the text. From left, the panels show (1) how day and night are products of the Earth's rotation, (2) how annual climate is affected by the Earth's orbit around the sun, and (3) aspects of form, light and color. Bottom three photos by Mark Humpal.

Click on the top image to see a larger version. Top: Huff and Strong's "Spiral of Life" panel that emphasized advancements made by Homo sapiens. HFA. Bottom left: The "Spiral of Life" panel was in storage at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History as recently as 2011. Bottom right: A PAJM panel showing stages in the development of different animals that is also in storage at SBMNH. The bottom two photos by Terri Sheridan.

Following the success of the PAJM project, Huff and Strong sought to offer their talents in the planning of another junior museum in Berkeley. The December 26, 1946, issue of the Oakland Tribune contained a short article entitled "P-TA Group Plans Junior Museum." "Working toward the establishment of a Junior Museum in Berkeley, Berkeley-Albany Council of Parent-Teacher Associations is working with other interested groups in the community. … Joining the P-TA group in planning for the museum are … William Gordon Huff and Ray Strong of the University of California." Apparently, a Berkeley junior museum never materialized.

The Alameda Naval Air Station

On December 11, 1941, four days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States declared war on Japan. Both Huff and Strong were pacifists (despite Huff's early activities in the ROTC) but each wanted to contribute "to the war effort on the home front. Since both were married with children, they claimed an exemption from active military service, provided they find defense industry work."1 This they were both able to do. Strong went to work at the Richmond Shipyards the day after he finished work on the Science Wing exhibits at the Palo Alto Junior Museum.2 Huff contributed in another way. He describes it in his informal biography:

How I happened to go to work at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, December 21, 1942 …. World War II was on and my friends were joining the service or working in defense plants. We were living in Berkeley at the time. I read in the paper there was an industrial school in Oakland that trained people for war jobs. I drove to where it was located and looked over the list of job training classes. Wood pattern making seemed like the one most related to my capabilities. I enrolled. It was a sixteen week course, but after six weeks I heard there was an opening at the Alameda Naval Air Station for a pattern maker. I visited the State Employment Office in Berkeley to ascertain if this were true. The woman who interviewed me phoned the Air Station and was able to talk to the superintendent of the division in which the pattern shop was a part. He said there was an opening and had her send me over. At the main gate I was given a pass to see Larry Brannan, Division Superintendent of the O and R Department.3 I felt at ease with Brannan when I met him. I told him of my limited pattern making experience—that my background as a sculptor gave me a feeling for the work. I convinced him and he signed me on.

There were six or seven workers in the pattern shop. I liked them all especially Eric Carlson, the boss, who had done work for the fair [the GGIE] and knew about me. We got along nobly and under his supervision I was able to turn out my share of the workload after a couple of weeks.

Finally the war came to an end. There was a sizable reduction in the work force, but I was not included in the lay off. It was an easy way to support my family so I remained. As a sculptor I became known to the 'top brass' who used my talents in many ways other than as a pattern maker.

The ANAS did indeed take advantage of Huff's skills. Huff made a number of bronze plaques for the Air Station—just how many is unknown. In a letter to Ray Strong (1984 or later), Huff wrote "I made reliefs large and small which are scattered around the country—and one which was installed somewhere in Antarctica."4

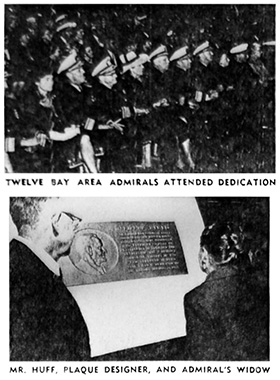

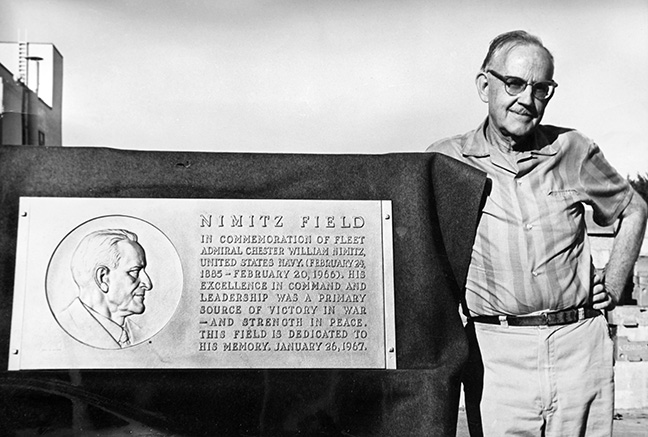

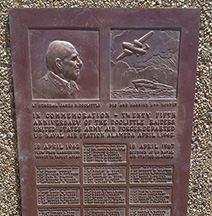

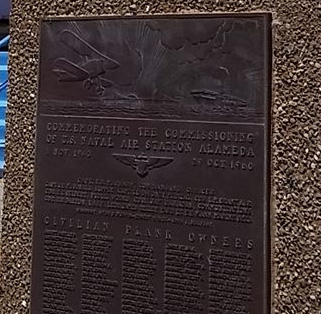

Three of Huff's Navy plaques can still be viewed today outside the entrance to the Alameda Naval Air Museum at 2151 Ferry Point Building #77, Alameda. The first one was made in October 1960 to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Station's commissioning.5 The other two plaques were made in 1967. The first of these was for the dedication of Nimitz Field on January 26, 1967, named in honor of Admiral Chester Nimitz. The second, dedicated on April 18, 1967, was made to commemorate the 25th anniversary of James Doolittle's raid on Japan.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Three photocopied photographs from the April 1967 issue of The Carrier, a Navy publication, concerning the dedication of Huff's Nimitz Field plaque. HFA.

Click on either image to see a larger version. Top: Huff standing with the Nimitz Field plaque. HFA. Bottom: Today, the plaque is mounted on the wall just outside the entrance to the Alameda Naval Air Museum, Alameda, California. From waymarking.com; posted by saopaulo1.

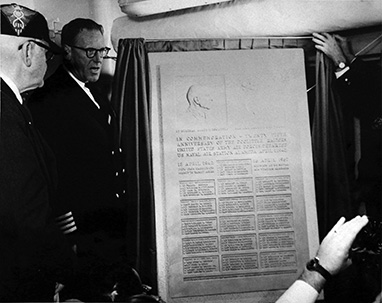

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Retired Lieutenant General James Doolittle, Air Force Reserve (left), at the dedication ceremony of Huff's plaque. HFA. Top right: Photo of the Navy brass unveiling the Doolittle plaque, April 18, 1967. HFA. Bottom left: Huff's bas-relief of Doolittle. HFA. Bottom center: Today, the plaque is mounted on the lawn outside the entrance to the Alameda Naval Air Museum, Alameda, California. From waymarking.com; posted by saopaulo1. Bottom right: This bas-relief is at the top right of the Doolittle plaque. This is a positive "cast" of the relief in metal (tin?). HFA.

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Huff's Nimitz Field, Doolittle, and ANAS commissioning plaques are all in this photo, although the Doolittle is turned away from the viewer. From waymarking.com; posted by saopaulo1. Right: A zoomed-in view of the ANAS commissioning plaque from the photo at left.

The ANAS was the home port for four aircraft carriers (the USS Ranger, USS Midway, USS Coral Sea and USS Hancock) and Huff probably made plaques for all of them.6 In a letter to Ray Strong (1984 or later), Huff wrote "I made 'portraits' of aircraft carriers which were dedicated aboard ship. (The inscriptions gave a brief history of that particular carrier)."7

Click on any image to see a larger version. Left: Huff's mold for his plaque of the USS Hancock, one of the aircraft carriers that was based at Alameda. HFA. Center: Another of Huff’s aircraft carrier plaques. HFA. Right: A mold of Captain Daniel K. Weitzenfeld USN. Weitzenfeld would later become a Rear Admiral and Vice Commander of the Naval Air Systems Command. HFA.

One project that began as a favor for a friend that turned into a newsworthy, international event attracting the attention of ambassadors, politicians and Navy brass was the sculpting of a bust of the Japanese bacteriologist Hideyo Noguchi.

The Hideyo Noguchi bust

Huff wrote a two-page, handwritten account of the story behind the Hideyo Noguchi bust. The story begins with Professor Charles Atwood Kofoid (1865-1947), Department of Zoology, UC Berkeley, who taught as a visiting professor at the Imperial University of Tokyo in the 1920s and who became a personal friend of Noguchi's. Kofoid "wanted his friends in Japan to know that there were others in this country [the U.S.] who shared his affection for their people—and even though relations between the two countries were becoming strained (in the late 1930s) there was a common ground for affection that flowed deeper than what appeared on the political surface." Kofoid's enthusiasm passed to one of his grad students, William H. Brown, who happened to be a friend of Huff's (Brown later became a professor of zoology at the University of Arizona). Brown thought that Huff was just the man to sculpt a bust of Noguchi. Supplied with photos of the bacteriologist, Huff worked on a model for the monument. He had completed the model by the time of the GGIE and wrote to the Japanese Consulate General in San Francisco about displaying it in Japan's exhibit at the fair. The offer was appreciated, however, it appears that Huff's offer was not accepted.1 Then, "international relations worsened and with the outbreak of war the Noguchi monument was shelved."

What began as a project with nothing to do with the Navy was to become a Navy project following the end of WW II. After Kofoid died in 1947, Bert W. Simmons, who had served as a Lieutenant Commander in the United States Navy, picked up the ball. Simmons had been stationed in Japan and had come to admire the Japanese people. He became "Superintendent of the Metal Manufacturing Division of the O & R Department, Alameda Naval Air Station, and expects to see the finished monument in Tokyo, dreamed of by Dr. Kofoid as an everlasting symbol of friendship between this country and Japan."2

In a November 3, 1956, ceremony at the Alameda Naval Air Station, Huff's bronze bust of Noguchi was presented to the Japanese Consul General. The bust was then flown to Japan where it was formally presented to the people of Japan on November 9. Huff was joined at the presentation ceremony by Naval Air Station Association President Arthur R. Thurston, as well as ANAS, Navy, State Department, and congressional representatives. The event received extensive media coverage.3

Noguchi was born in Inawashiro, a small town about 130 miles north of Tokyo. This is the location of the Hideyo Noguchi Memorial Museum, but the Noguchi bust is about an eight-minute drive away in Kamegajoshi Park, which includes the ruins of Inawashiro Castle. Huff's sculpture is located on a high point within the park, probably within the ruined castle's perimeter.

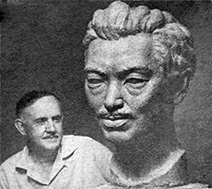

Click on any image to see a larger version. Top left: Huff with his finished bust of Hideyo Noguchi. HFA. Top center and right: Newspaper articles concerning the Noguchi bust. The two center articles are from (the top) the October 7, 1956, Oakland Tribune, page 31, and the November 10, 1956, issue of The Bennington Banner, page 1. The two articles on the right are from (the top) the November 18, 1956, issue of Shin Nichibei, The New Japanese American News and the November 1956 issue of The Carrier, a Navy publication. The two center articles are from newspapers.com; the Shin Nichibei article is from the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, and The Carrier article is from the HFA. Bottom: A photograph of the Noguchi bust presentation ceremony in Japan. HFA.

The Noguchi bust at its present location in Kamegojoshi Park in Inawashiro, Japan. The photo was obtained from a Japanese web page in September 2015 but it has since been removed.

On the next page we'll examine projects, both realized and unrealized, that Huff was involved in between 1942 and the 1970s.