The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Alexander’s Photographs

by David K. Smith

For an analysis of the Expedition’s route and adventures, see

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Part I—Route and Adventures

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Appendix

NOTE: Clicking on the blue text links to more information in the Appendix.

This is an analysis of some 120 photographs taken by Annie Montague Alexander that were placed in a scrapbook chronicling the 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition. This scrapbook now resides in the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP) Archives.

The Fossil Lake Expedition was Alexander’s first major fossil-collecting venture on behalf of UC Berkeley’s Department of Geology (there was no Department of Paleontology until 1909). She was 33 years old in 1901 and was quite a photography buff. In fact, a comment Alexander made in a January 1901 letter to her lifelong friend, Martha Warren Beckwith, suggested that she had aspirations to become a photographer: “Were I not a fossil hunter I might be tempted to try my luck with the camera ….”1

Alexander was clearly serious about her photography, even intending to process her own photographs. Writing to Beckwith after the expedition she said:

I certainly intended to send you photographs of Crater Lake long before this but I’ve been waiting to fix up a dark room …. I’ve given up the venture however—something rare for me for I’m generally rather self indulgent where a thing I want is in question. The trouble is I haven’t the time to give to it ….2

I presume that Alexander ended up having the film professionally processed, considering her comments to Beckwith, the large number of images, and the number of copies she had made.

Apparently, one camera for the Expedition was insufficient. Two months before heading up to Montague, the Expedition’s departure point, she wrote to Beckwith:

When we have had all we wanted of Fossil lake we shall cross over and strike a road to Crater lake for I must take some good pictures of that lake seeing we shall be so near and I shall have my two cameras with me.3

Alexander provided no details about her two cameras in either the scrapbook or her letters other than one being larger than the other. But being wealthy, it makes sense that she’d get herself quality cameras. It’s safe to say that she had two box cameras, as opposed to the lower-end, folding cameras of the day, based on the size of the prints. Most of the inexpensive folding cameras in 1901 produced small prints around 3.5 x 3.5 inches; even low-end box cameras could do 5 x 4-inch pictures. More expensive cameras could take larger pictures.

The vast majority of Alexander’s prints are 4.5 x 3.5 inches but about 17 have varying widths and heights. There are a handful of larger images in the neighborhood of 6.25 x 4.25 inches—I believe that these were taken with Alexander’s bigger camera. A couple things may account for the size differences in photographs taken with the smaller camera: inconsistency in the film processing and/or manual cropping (the photographs have no borders).

Box cameras that took pictures using both glass plates and roll film were fairly common around the turn of the century. Considering that the expedition was traveling over rough terrain, Alexander used roll film; this is supported by the July 28 scrapbook entry that mentions a Doctor Burnett who “brings us a roll of films from Mr. Schilling.”

Box cameras usually had two tripod sockets so that one could mount the camera for landscape or portrait orientation. The majority of Alexander’s photographs were probably taken using a tripod. Her larger camera was lost over the rim at Crater Lake on July 24 but she still needed the tripod for the smaller one; in her description of the return hike from Llao Rock with Furlong the next day, she told Beckwith: “I dared not look below and had it not been for my tripod to steady me I doubt if I could ever have done it ….”4

Alexander took a photograph of John Merriam with his box camera mounted on a tripod during the 1905 Saurian Expedition to the Humboldt Mountains of Nevada. The camera appears to have a bellows and a pneumatic shutter release; perhaps Alexander’s cameras were similar.

Things to know before you begin

It is recommended that one read Part 1, The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Route and Adventures prior to diving into Part 2—many of the references will make more sense. Part 2 features several “then and now” photographs. I took the majority of the “now” photos during a July 5-15, 2022, retracing of Annie Alexander’s route on which I was joined by my wife Colleen Whitney and friend Kirk Hastings. Colleen was UCMP’s first staff webmaster from 2000 to 2004 and Kirk is a retiree from the California Digital Library, a unit of the University of California Office of the President (UCOP). A number of random photos taken during the retracing accompany the “then and nows.”

An online pdf version of the Fossil Lake scrapbook can be seen on the UCMP website. Each photograph in the pdf is identified by its digital archive file number, e.g., 001_1901.tiff, 002_1901.tiff, etc., but to keep things simple here, I refer to the photographs as Photo #1 (for 001_1901.tiff), Photo #2 (for 002_1901.tiff), and so on. The numbered scrapbook photographs are not to be used without permission of UCMP. I took all of the 2022 color photographs except where indicated.

I make several references to scrapbook entries. The pdf of the scrapbook (see the link above) includes all the entries; only those entries that contain information relating to the Expedition’s route, camps, and adventures can be found in Part 1.

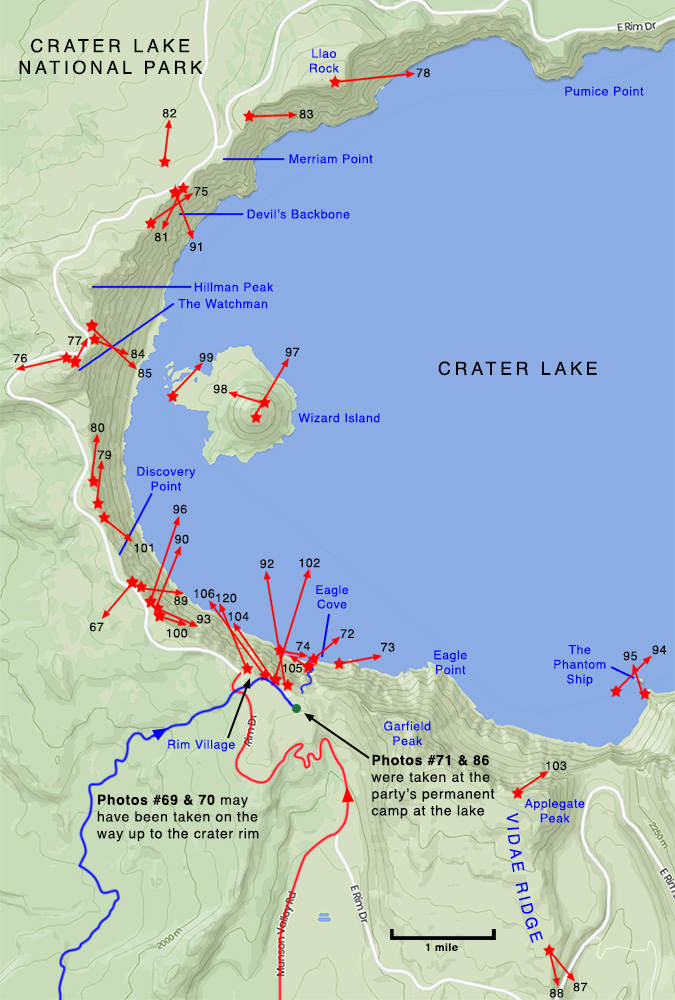

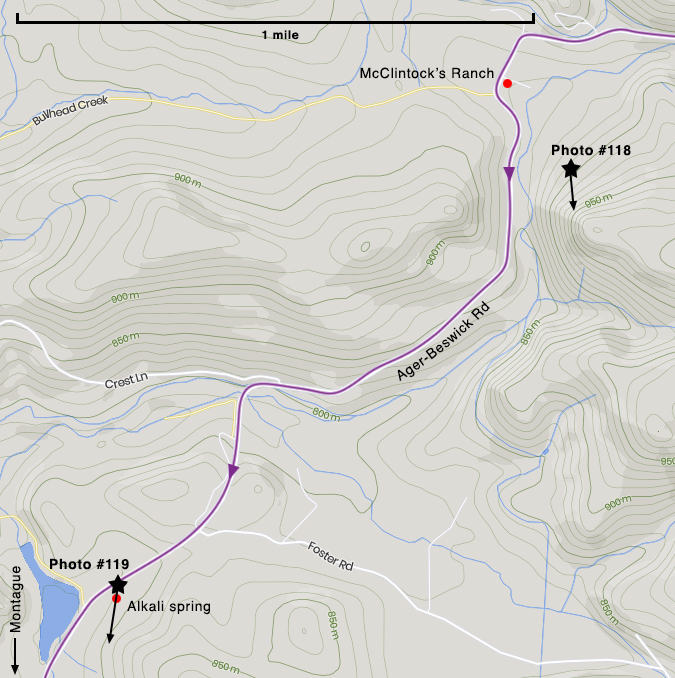

The maps in Part 2 cover only those areas where Alexander took photographs—for maps that show the Expedition’s route in its entirety, see Part 1. The maps were built upon screen captures from Google Maps and mapcarta.com. The stars on the maps are my best guesses as to where Alexander stood when she took her photographs and the arrows indicate the direction she aimed her camera. As in Part 1, the routes indicated on the maps can be identified in this way:

The 1901 Expedition route is shown in blue

My 2022 retracing route is shown in red

Where the two roughly overlap the route is shown in purple

Except for the four cardinal directions—east, west, north, and south—all compass directions are abbreviated (e.g, southeast is SE, north-northeast is NNE, etc.).

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition began with five participants: Alexander, Mary Elizabeth Wilson (who wrote the scrapbook entries), Herbert William Field Furlong, William Buckhout Greeley, and Ernest (the cook). Willis, a 14-year-old boy, joined the Expedition about four days after it set out from Montague.

Fossil Lake Expedition photographs: then and now

Three men are easy to spot in Photo #2—Greeley (somewhat blurred at the left), Ernest at the wagon, and Furlong by the tree at the right—but two other men are present. One, a well-dressed man in a tie is standing just behind the right end of the wagon—his hand is on the fence rail. To the right of him there is another man with white suspenders walking away, just to the right of the fencepost; see a closeup. Based on the shadows, it may be late morning. Ernest could be preparing lunch, however, it seems to me that this photograph was taken after breakfast on June 1 and the party is beginning to pack up. Note the smoldering fire. For some reason, Wilson’s basin-like hat (you’ll see her wearing or holding it in other photographs) is hanging from a tree branch well above Furlong’s head. Most of the camping gear has been packed; the white bundle at the far right is probably the women’s tent. One of the women’s cots is behind the bundle. Alexander mentioned the cots in a May 2, 1901, letter to her friend Martha:

We have ordered two cots—they will come in very handy when there are no pine needles around and we shall have our tent, camp-stools, and a table so ought to be very comfortable.5

At the time of the retracing I did not realize that Edgar Ball’s land extended up into the forested hills—I thought that his ranch was down on the flats at the base of the hills. It wasn’t until later that I discovered the full extent of Ball’s land6 (see my map, above) and, once I had this information, I went back to Google Maps to scan the hills for signs of the buildings in Alexander’s Photo #4. I found a fairly flat area with a drop-off like that at the back right of the photograph that seemed like a possible location for the buildings (see the map). Although there are no ruins visible in Google Maps Satellite View, a somewhat overgrown forest road can be seen heading over to that area.

This photo confused me for the longest time, primarily because I knew little about ice caves and how they might be accessed. In a superficial inspection of the area between Butte Creek and Red Rock Road using Google Maps Satellite View, I saw nothing that would suggest the presence of ice caves. I knew that there were ice caves at Lava Beds National Monument but that was a good 18 miles east of Butte Creek and nothing about them resembled Photo #5. In my search for information about ice caves in Butte Valley, I stumbled upon pictures of Crack in the Ground, a two-mile long volcanic fissure just a few miles NW of Christmas Lake—it looked almost exactly like Photo #5. Was the photograph out of place in the scrapbook? Did the party visit the Crack about three weeks later during its time up at Christmas Lake? Colleen, Kirk, and I visited Crack in the Ground and tried to find a match for Photo #5 but came up empty. And for good reason.

After returning from the retracing, I finally realized my mistake about the “Ice Caves” by examining the Expedition’s route across Butte and Red Rock Valleys more carefully and rereading Alexander’s letters to Beckwith:

Last Sunday we spent just over the range in Siskiyou Co. N.E. of Mt. Shasta. It was a sage brush plain enclosed by mountains. There were two or three old lava flows across it and in one of these were ice caves that we visited. The ice hung in stalactites from the roof and covered the floor and it was all we could do to keep our footing.7

Alexander makes it pretty clear where they encountered “two or three old lava flows” so I took another look at the area on Google Maps. I still couldn’t recognize anything that I’d call a lava flow but I did see three, long, north-south-oriented volcanic ridges or escarpments that are quite obvious in Google Maps Satellite View, even with low magnification. So I zoomed in to the maximum to examine these “ridges.” To my surprise, several places along them looked just like Crack in the Ground, complete with fissures. Looking at them in Google Maps Satellite View’s 3D mode, it became clear that these “ridges” were actually the fractured, forward faces of three successive lava flows, the most easterly one being the lowest in the sequence. The west and central ridges have fissures that could provide access to ice caves but it might take many hours to locate the precise spot where Photo #5 was taken.

Alexander took Photo #6 about 200 yards north of the current ranch owners’ driveway along Willow Creek and Red Rock Road. If the driveway was in the same location 121 years ago, and Alexander and crew left the Davis Ranch by way of it, then she may have taken the photograph just as the party set out for Merrill. If so, they got a slow start because, based on the shadows, the sun seems to be high overhead.

It was fairly easy to locate where Photo #8 was taken, thanks to Google Maps Street View, but Photo #7 confounded me for a long time. A month or two before leaving for the retracing, I made a more concerted effort to find its origin point. I returned to the Google Maps Satellite View for #8, rotated it to the west, and realized that #7 and #8 were taken from the same spot!

In #10, a Klamath woman and her dog stand outside a tule hut with Herbert Furlong. Note the sidearm Furlong’s carrying. Taken together, I think that Photos #10 and 13 suggest that the Expedition took the northern route shown on the above map. That hill behind Furlong may be the lower slope of either Bug or Spring Butte.

Photo #11 probably shows the interior of the lodging pictured in Photo #10 as seen from the doorway. Light appears to be coming from a “skylight” and there is a sleeping woman at the left. The walls of the construction are tule rushes that were tied together. Photo #12 is a nice portrait of a Klamath man sitting on the steps of a cabin with glass windows.

I found the general direction that this photograph was taken using Google Maps Street View—the background hills were easy to recognize. Of the two most likely routes taken by the Expedition (see my discussion of this section of the route in Part I), I favor the more northerly one since the distant hills seem closer in Alexander’s photograph than they do in mine.

Long before the retracing of Alexander’s route I checked Google Maps Street View along the Booth State Scenic Corridor of OR-140 thinking that this was the most likely place to find tuff exposures but saw nothing resembling Photo #16. During the retracing, as we approached Lakeview, I saw a pointy peak behind us that looked like the one in the background of Alexander’s photograph. Back at home, I took another look at Google Maps Street View and I’m pretty sure I found where the photograph was taken: about one to one and a half miles north of OR-140 along the foothills of the mountains looking NNW.

Since I scanned Alexander’s photographs at a high resolution, I can zoom in to see details that might be missed otherwise. At the front left of Photo #18 one can see the remains of a fire and what look like a couple of blankets lying on the ground nearby. Just beyond the fire pit is a stump with somebody’s lace-up boot laying across it. A few people are gathered around a table at the center of the photograph. Seated on the left side are Wilson (it looks like Alexander’s hat but Wilson’s body) and Greeley. On the right side there are two men, one is probably Furlong and the other is a guest, a bearded man in a dark, long-sleeved shirt and a dark hat. Ernest is standing, facing the camera holding something unidentifiable on a stick or skewer; see a closeup. Willis, as usual, is nowhere to be seen. Perhaps the guest was the one who reportedly said that the Warner Canyon rocks are “very ‘assymmetrous'” in the June 14 scrapbook entry.

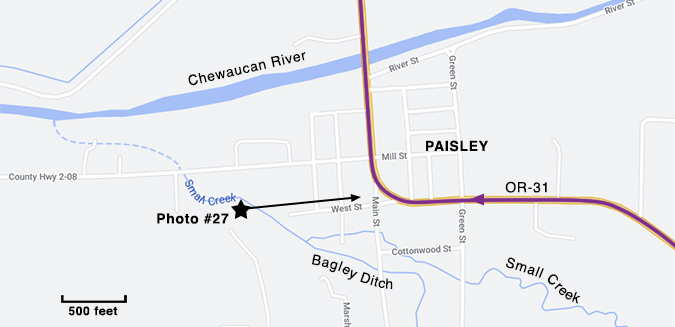

Before setting out on the retracing, I had doubts about whether the Expedition went from Warner Canyon to Paisley via Clover Flat Road, but once we found the location for Photo #19, I knew we were on the right track. So I kept a sharp lookout for Photos #20, 25, and 26.

In March 2024 I finally learned where Bryan’s Ranch was located (a couple miles south of where Photo # 19 was taken) so it’s possible that one or more of the scrapbook photographs from the Bryan Ranch and Clover Flat Road area were not placed in chronological order. Assuming no backtracking in the Clover Flat area, the photographs should have appeared in this order (from south to north): Photos #21-24, 19, 25 and 26, and then 20. But there is a possible explanation for the photograph order.

In Alexander’s Photo #20, it’s hard to see but there’s actually a low rise in the left foreground that conceals most of what appears to be a building. Look below the sharp peak on the horizon, left of center, and just to the left you’ll see the peaks at both ends of a long roof(?); see a closeup. There’s no structure in that area today.

If I am right about Photo #18 being taken at the Warner Canyon camp, then it makes sense that Photos #21-24 were taken at Bryan’s Ranch, despite the appearance of the photographs being out of place chronologically.

Photo #22 is of Greeley, Photo #23 is of a well-armed Alexander (that may be Furlong’s gun belt she’s wearing), but Photo #24 is the most interesting. Wilson is seated by the women’s tent, writing. Hanging on the rope above her is what could be a dark coat or long skirt, two nightgowns, and an unidentifiable article of clothing. Alexander’s hat is on a stump at the far left. Wilson could be writing in a journal or maybe editing field notes dictated to her by Furlong. Regarding the latter, Alexander wrote to her friend Beckwith: “… [Wilson’s] conscientious writing up of the geological notes, Mr. Furlong painfully dictating and Mary serenely putting it down in good form.”8

Unfortunately, none of Furlong’s field notes remain in the UCMP Archives. At first I suspected that John C. Merriam took all the vertebrate paleontology field notes with him when he left UC Berkeley in 1921 for the Carnegie Institute in Washington, DC, but, after checking with the Institute, that does not seem to be the case. The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, which has a good deal of Merriam’s paleontology-related correspondence and other papers, doesn’t have the field notes either. Where all the pre-1921 vertebrate paleontology field notes disappeared to is an ongoing mystery.

I was unable to locate where Alexander took Photo #25 during the retracing but I sent the photograph to Diane Elder later (the Elder family purchased the old Bryan Ranch in Clover Flat and Diane lived there for a time) and she recognized the scene immediately. As it turned out, all I had to do was turn around after I found the origin point for Photo #26 (see below)! In the latter shot, the view is to the NNE into the Moss Creek valley. Photo #25 was the view to the SE toward Clover Flat (note the absence of trees). The two photographs were not taken from the exact same spot though because you can see in Photo #25 that Alexander is a few yards west of where she stood to take Photo #26 (below).

The large white building in the distance is Paisley’s first schoolhouse, built in 1895. The structure was moved across town in 1905, became a Catholic church, and is now a private home.9 The somewhat grayer building in front of the school is still standing today on the NW corner of Green Street and West Street (this east-west portion of OR-31 is called West Street within the Paisley borders).

“Woodward’s Gardens” was an early name for what would become today’s Summer Lake Hot Springs, an eco-friendly resort with cabins and spots for RVs and tent campers. Colleen, Kirk, and I spent the night there. I showed Alexander’s photograph to the current owner but he had not seen any pictures of the hot springs from that long ago, however, he did direct us to some ruins (pictured in my above photo) north of the hot springs and closer to the lakeshore. The ruins were old but they didn’t look 121 years old to me.

Alexander’s photograph, showing two buildings at the “Gardens” (see the inset), was taken from higher ground south of the hot springs and OR-31. In the enlargement of the buildings you can make out the line of the road (today’s OR-31) in the foreground. Unfortunately, the land south of the highway is all private property so there was no chance of our getting close to where Alexander was standing when she took Photo #28.

These photographs are of the tuff exposures—known as the White Hill Creek tuffs—on the south side of OR-31 about three miles west of the hot springs. I didn’t spend much time trying to find the precise spots where Alexander took Photos #29 and 30.

Photo #31 is a great view of Summer Lake, looking SE from a little over 11 miles north of the hot springs and west of the highway. The road (today’s OR-31) is clearly visible and the buildings mark the location of the Foster Ranch where Alexander and the others camped on June 19. How do I know it’s the Foster Ranch? Elaine Condon, a Silver Lake historian and the woman who had put me in touch with the Elders, saw the photograph and recognized the house partially hidden by trees. To my surprise, she told me that her great great grandfather built the house, completing it in 1889!10

Fremont Point is the prominent point on the horizon in this view to the north. I think that Alexander took Photos #31-33 while on a hike or ride up the slope of Winter Ridge shortly after leaving the Foster Ranch. Photos #32 and 33 may have been taken around the same place, the former presenting the view to the north and the latter the view to the south. I think that we could have found where Alexander took these somewhere along NF-3143 if not for the “Private Property” signs.

The June 20th scrapbook entry reports “We see Indian pictures at the summit of the grade and leave some valuable additions to the collection.” Hopefully, none of the petroglyphs in the above photograph date from 1901!

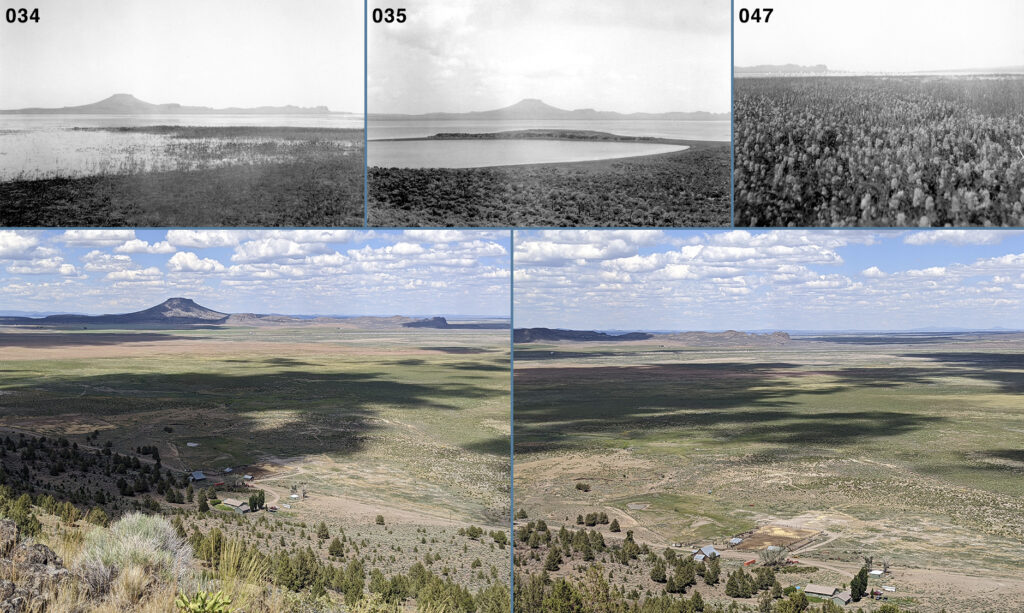

Table Rock is the prominent flat-topped butte in Photos #34 and 35. Photo #47 was taken after the party’s trip to Fossil Lake but it makes sense to include it here. I suppose that Silver Lake is considered an intermittent lake—when it rains a lot, there’s water, when it doesn’t, it’s dry. As you can see, it was quite full when Alexander and company visited in 1901; today, it’s not even shown on Google Maps.

Being down at ranch level would have helped a lot in establishing where Alexander took these photographs, but in studying Google Maps Satellite View and my own photos, I came up with what I think are decent approximations for the locations. I took three photos from the rim, each about 40 to 50 yards apart. By comparing my photos to Alexander’s and paying attention to the notches in the distant ridge and the dry or shallow areas near the lakeshore, I decided on the origin points you see in the above map.

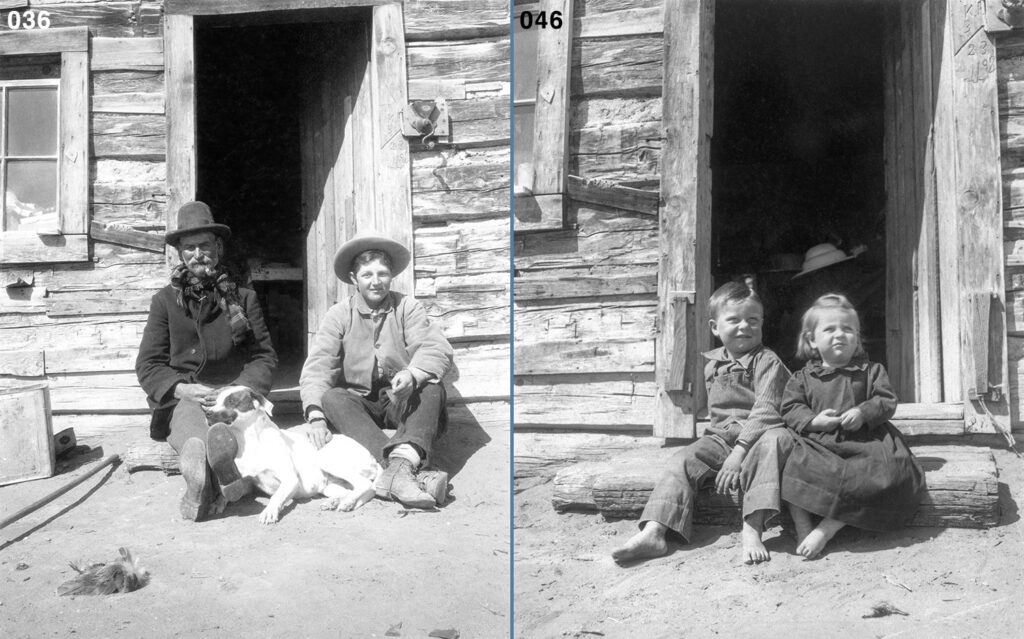

… captions were provided by Reuben Long in his 1964 book, The Oregon Desert, in which these two photographs appear. For Photo #36:

George Duncan (left), first postmaster at Silver Lake, was the first person to recognize the value of the tons of fossilized bones on the bed of Fossil Lake. He interested scientists, who came and carted away wagonloads of them. Everett Long (right), now deceased, was Reub’s [Reuben Long’s] elder brother. The dog’s name was Bugle. Pictured is the doorway of the cabin where Reub grew up [at Christmas Lake]. At the right of the door is the coffee mill. Every homesteader ground his own coffee in those days.11

For Photo #46, taken after the party returned from Fossil Lake:

Reub Long and his sister Anna Long, about 1902 [1901], in front of the cabin at Christmas Lake where they were raised. Reub, aged four; Anna, aged two.12

Read more about Reuben Long, his father Alonzo Welch Long, and the Long homestead.

There are some interesting things to notice about these two photographs. For one thing, there’s a dead bird lying near George Duncan’s feet in Photo #36. Several numbers and symbols carved into the door frame can be seen in both photographs. Some on the left side of the doorway look like they might represent the cattle brands of local ranchers; see an enlargement of the carvings. Wilson can be seen sitting just inside the cabin door in Photo #46. She’s sitting sideways to the doorway and her upper body is hidden behind the door. She’s holding her white, basin-like hat on her knees with her left hand; the back of her wrist is visible. Alexander must have sent copies of these photographs to the Longs.

Alexander took more than one photograph of Reub and Anna. Connie Soja found a similar, but different, picture of the kids on findagrave.com (retrieved September 8, 2022).

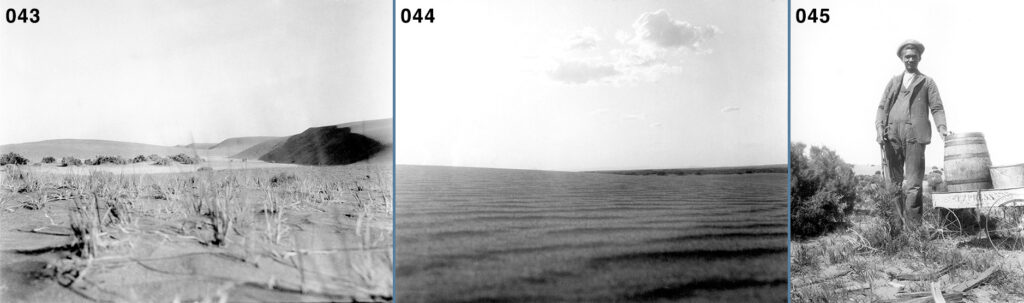

I say this is Fossil and not Christmas Lake for the following reasons: (1) The scrapbook entry accompanying Photo #37 reads “We reach Fossil Lake at noon and establish our first permanent camp.” (2) Christmas Lake was much broader near the Long residence—these photographs suggest the small, spring-fed pond that was Fossil Lake. (3) What appears to be a distant hill on the horizon in both actually may be only a sand dune. But just to the right of the dune in Photo #41 you can make out a flat-topped hill (see the inset). I believe this hill can be spotted from Christmas Valley Highway on a line SW from Fossil Lake (see my photo accompanying Photo #40 below). The other inset is of a tent or lean-to-like structure of some kind on the far shore.

Photo #41 was taken farther to the north along the lake shore than #37. In Photo #37 you can see the hoof prints of a few horses disturbing the soil along the near shoreline. In Photo #41 the hoof prints of a single horse are visible, as is one shorebird (a plover?).

Alexander clearly tried to capture beautiful skies and light effects in many of her photographs, but the black & white format was not really suitable for this. I’m sure that most of her attempts would be much more impressive in color.

Nothing about the fellow in Photo #39 suggests that it’s Furlong so I’m guessing that it may be the party’s host at Christmas Lake, Alonzo Long. Alonzo turned 53 in 1901.

The day before the plover hunt, a scrapbook entry reads “The weather is exceedingly cold, and we decide that this lake is well named.” The men in the photographs do look dressed for cold weather and maybe the gent in Photo #41 wore the bandanna for warmth; see a closeup. Note the solitary cow or horse grazing beyond the fence in Photo #38.

In the scrapbook, Photo #48 has three days’ worth of entries below it, all dealing with the “Sandstone Ridge” adventure. When I first saw this image I thought that it might be of Summer Lake and out of place in the scrapbook, but the hills are wrong. If it was in the right place, then what lake would the party pass while out looking for the “Sandstone Ridge”? Perhaps it was Thorn Lake. But the hills there didn’t match up either. Only after the retracing did I realize that it was actually the eastern shoreline of Silver Lake. I blame my inability to recognize it on very poor quality Google Maps Street Views from 2009 in which the distant ridge beyond the lake is invisible. The Street Views south of the OR-31/Old Lake Road intersection are low resolution and the lighting is bad; those north of the intersection (like the one above) are from 2021 and somewhat better.

This was another photograph that confused me for a long time. I originally thought that Photo #49 was taken near Table Rock so Colleen, Kirk, and I made a point of visiting it. But we left there without finding any view that could possibly match up. It was months after the retracing before it dawned on me where it was taken.

I studied Photo #49 and the accompanying scrapbook entry again. Two things finally led me to the truth: (1) I could rule out Table Rock because the size of the trees in the photo indicated a smaller butte or cliff and (2) the scrapbook entry says “We go back to our camp at Silver Lake.” I should have given more credence to that entry. It became clear that the photo was of the Expedition’s camp on the Duncan Ranch. The line of cliffs are those west of and above the Ranch and that visible gap is the mouth of Duncan Creek. The view is to the NW. If Alexander turned 90 degrees to the right she’d be looking across Silver Lake.

The large monument in the cemetery was erected three years before the Expedition passed through to honor the memory of 43 people who died in one of the deadliest fires in Oregon history. An account of what transpired that Christmas Eve appears on pages 854-857 of Rose, A.P., R.F. Steele, and A.E. Adams. 1905. An Illustrated History of Central Oregon: Embracing Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Crook, Lake, and Klamath Counties, State of Oregon. Western Historical Publishing Company. This book can be viewed on Internet Archive (archive.org).

In a letter to her friend Beckwith, Alexander wrote a description of George that would go well with Photo #51:

He and his son [Felix] have a little ranch here on the lake. It must be terribly lonely for him for he loves to talk but he pegs away at his books and sits on his veranda with his pipe in his mouth looking toward fossil land and picturing how things must have looked in the days of 60,000 years ago.13

The July 11 scrapbook entry says that George got a shave. His beard does look much shorter here than it did in Photo #36 so perhaps this photograph was taken the morning the party left Silver Lake on July 15.

The next photograph in the scrapbook was taken at least four, maybe five, days later and I find that surprising. The party covered more than 90 miles in that time. Was the landscape so boring that it wasn’t worth taking a photograph? Had Alexander run out of film and couldn’t restock until Fort Klamath? I suspect the latter but we’ll never know for sure.

The scrapbook contains ten photographs that can only be the eroded tuffs along the banks of Annie Creek which parallels OR-62 on the east. The first three, Photos #52-54, are followed by two shots of Annie Spring (Photos #55 and 56), and then seven more shots of the tuffs, Photos #57-63. I believe that the first three were taken on the way to Crater Lake (on July 20) and the remaining seven on the way back (on August 2), since the party backtracked to Fort Klamath after leaving the lake and Alexander admits to hanging back to take more photographs of the canyon (see my discussion of Photo #106 below). The angle of the sun is about the same in all ten photographs so that doesn’t help decide the matter, but, if I am correct, then someone (Wilson?) chose to group all the Annie Creek tuff photos together, separated by the two Annie Spring shots.

Of the three, pre-Spring tuff photographs, I was only able to locate where Photo #53 was taken. If I took my time and spent a few hours following Annie Creek—preferably with the sun high overhead—I’m confident that I could find where Alexander took all ten.

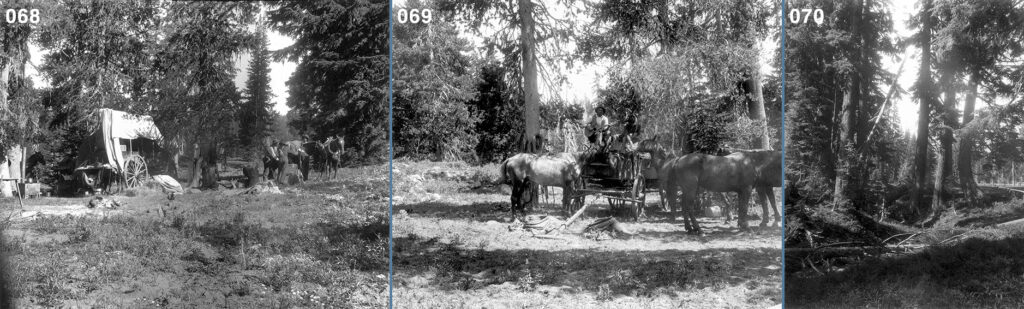

I’m guessing that Photo #68 was taken the morning of July 23 when the party was preparing to move its camp to the crater rim. The three men are, from left to right, Furlong, Willis, and Ernest. Four horses are visible: There are the two obvious ones that the men are dealing with but there is another in the shade at the far left and the legs of the fourth can be seen between the wagon’s rear wheels. Note the pile of hay next to the wagon.

The wagon is clearly in a different location in Photo #69. Perhaps the horses are getting a rest from hauling the wagon up to the crater rim, but then, the wagon doesn’t seem to be loaded. Ernest plays his guitar while Furlong feeds something to one of the horses.

Alexander had this to say about Ernest in a letter to Beckwith: “He has brought along his mandolin and guitar and is very entertaining with his endless conundrums.”14

The forest scene captured in Photo #70 could have been taken on the way up to the crater rim or maybe near the rim camp.

Alexander described their camp in a letter to Beckwith:

We are camped in a clump of firs, not far from the trail and are as comfortable as any could wish. Our tent is in the shade all day so it keeps cool. We have a canopy over our dining table, a stand for our wash bowls, and Earnest has fixed up his kitchen with a cupboard and shelves so we are all about as proud of the appearance of our camp as we can be. Earnest is so happy as he works all day—there never was more [sic] good natured fellow.15

I was told by a park employee that the original trail down to the lake was just below the Crater Lake Lodge. He said traces of it remained but I was unable to see anything that could be called a trail either from the rim or in checking Google Maps Satellite View later. In November 2022 I came across a 1931 USGS map of Crater Lake that shows two paths down to the lake. The primary trail begins west of Victor Rock, the location of today’s Sinnott Memorial Overlook, but the one I think Diller and Alexander used begins east of the Lodge.16

Photos #75-85 were all taken north of Discovery Point and I suspect that Alexander took them while on her July 25 hike with Furlong to and from Llao Rock.

In rereading Alexander’s letters to Beckwith, I realized that on August 1 Alexander and Willis hiked up Garfield Peak, across the meadows you see in my photo at the lower right, and down the steep, eastern side of Vidae Ridge to reach Sun Creek:

Sun Creek begins about three miles around to the East of where our camp was, Martha. There is a big mountain to climb, then a comparatively level stretch for a mile or more, then a very steep descent to reach the creek.17

Regarding Alexander’s return trip from Sun Creek back to camp, she says in the same letter, “I should have tried to cut off some of the climbing had I not left my camera on the ridge.” After reading this, I was confident that Photos #87 and 88 were taken from Vidae Ridge on that hike. But in another letter Alexander pointed out to me that I was wrong—right ridge but wrong outing. She wrote: “The view of Sun Creek Cañon was taken on a day when we attempted to make the trip on horse back and failed.”18

This must correspond with the July 26 scrapbook entry: “First expedition to Sun Creek. We see two deer but the gun is ‘on the other saddle.'”

Perhaps Alexander and Willis decided to hike instead of ride to Sun Creek on August 1 because they didn’t want to risk an accident with the horses on the steep descent from Vidae Ridge.

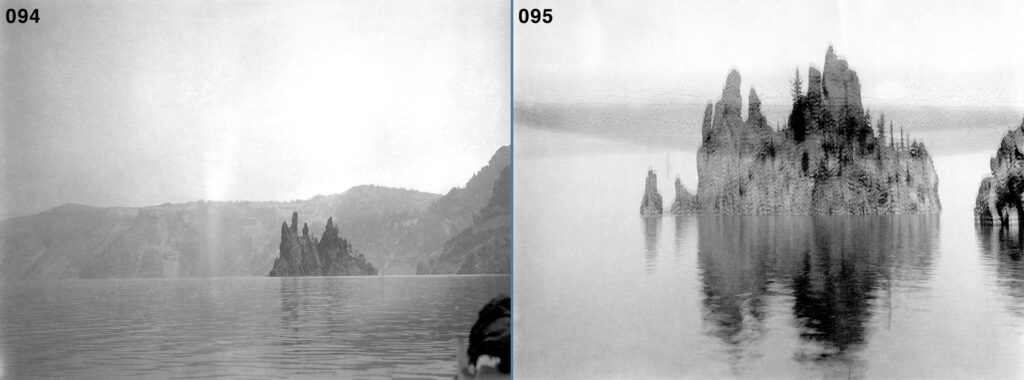

In the July 27 scrapbook entry accompanying Alexander’s photograph it says “in the afternoon [we] walk along the rim to get a picture of the sphinx,” so I assume that this rocky prominence was the mysterious sphinx. I have found no online reference to any such formation at Crater Lake but the background helps identify the origin point for this shot. The view is almost due east. In the middle of the wide gap between the trees is Sun Notch, with the slopes of Mt. Scott (left) and Applegate Peak (right) on either side.

I wonder why Willis doesn’t appear in more of Alexander’s photographs. Did he make an effort to avoid being photographed? Alexander said little about him in her letters to Martha and we don’t even know his last name so I guess we’ll never find out his story.

Alexander didn’t know it but she was photographing the future home of the Sinnott Memorial Overlook. What she also didn’t know was that John C. Merriam would be instrumental in the planning, design, and financing of the Overlook. Alexander was displeased with Merriam when he left Berkeley for the Carnegie Institute in Washington, DC, but like her, Merriam considered Crater Lake a special place. I wonder if Alexander ever learned about his involvement with the Overlook’s construction and, if she did, how she felt about it. It was opened to the public in 1931.19

Except for Photo #120, which was placed at the back, this is the last Crater Lake photograph in the scrapbook. The party left the lake on August 2 and rendezvoused in Fort Klamath. Alexander arrived there 2.5 hours after the others, partially because she wanted to take more photographs along Annie Creek. She really didn’t want to leave Crater Lake:

It wasn’t a very happy day—I stayed behind the rest so as to take pictures of the cañon and Pat, my horse, got away from me. I couldn’t blame him for wanting to go back to Crater lake but he shouldn’t have left me so in the lurch when I was so tired, footsore, hot and the road dusty. I walked back four miles and then a camper lent me his horse.20

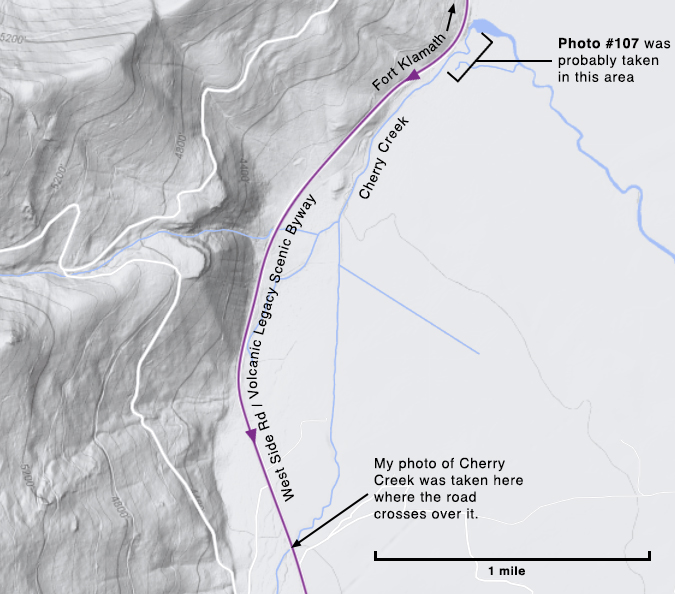

As I noted way back in my discussion of Photos #57-63, I am of the opinion that Alexander shot the last seven of her ten Annie Creek photographs on August 2 while en route from the lake to Fort Klamath.

The man in the boat doesn’t look like Furlong to me, but then, up to now, we haven’t seen any photographs of a hatless Furlong, and besides, Alexander says in a letter to Beckwith: “The picture of Mr. Furlong in the boat was taken at Budd Spring a stream about a mile long that emptied into Klamath Lake.”21

I think that what Alexander refers to as “Bud Spring” is actually Odessa Creek, a stream that is about a mile long. If the man with the rifle is Furlong, one might assume that the boy is Willis, but I don’t think so. In Photo #99, the fellow rowing the boat in the cove at Wizard Island is definitely Willis and he has the build of a young man. Photos #109 and 110 are of a younger boy with a different hat and bib overalls; perhaps he was a guest at the resort. See a closeup comparing the two boys. The dog certainly was not an Expedition member.

Both Photos #113 and 114 were taken from the vicinity of “Big Point” on the Topsy Grade Road. Topsy Grade proper is a section of the road that climbs the steep canyon wall. At “Big Point” there’s a sharp bend in the road curling around a dynamited cliff with a 1000-foot drop down to the canyon bottom on the other side. From period photos I’ve seen, it hasn’t changed much since Alexander passed by.

On July 14 Colleen and I closed the Fossil Lake Expedition’s loop (Kirk drove back to the Bay Area the day we left Crater Lake), returning to the intersection of 11th and East Webb Streets in Montague at 5:54 PM. Alexander’s trip lasted 76 days; ours lasted ten. On the 15th we pulled into our driveway at 2:13 PM, ending an enjoyable adventure that exposed us to some lightly populated, lightly traveled, and beautiful areas of northern California and southern Oregon.

Thanks to one of Alexander’s letters, we know that Photo #120 was taken with the “big camera” that she lost over the crater rim on July 24. She told Beckwith “The profile view of the side of the crater, in the larger size was the last picture my big camera took.” The print is larger than the others, being 6.25 x 4.25 inches. As it turned out, Alexander only took five photographs with this big camera:

I’ll send you some of the photos I took while at Crater Lake. They might be a great deal better but the films I over exposed and you know I lost my big camera when I had taken only five pictures.22

Of the five photographs Alexander claims to have taken with the camera, it seems that only four made it into the scrapbook: Photos #19, 20, 106, and 120 (unless the fifth was severely cropped or unusable).

- The Joseph and Hilda Wood Grinnell Papers, BANC MSS 73/25 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Box 5, Letters from Annie Montague Alexander to Martha Beckwith 1899-1940 undated. From a January 12, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From an undated but 1901 post-expedition letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a May 2, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a July 26, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a May 2, 1901, letter.

- From a 1957 Metsker Map of Siskiyou County that gives the names of property owners, pages 057 and 058, found at Historic Map Works. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Grinnell Papers. From a June 10, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a 1901 post-expedition letter.

- From The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- Personal communication. A June 12, 2022, email from Elaine Condon.

- From page 33 of Jackman, E.R., and R.A. Long. 1964. The Oregon Desert. Caxton Printers, Ltd., Caldwell, ID. 407 pp.

- Ibid. P. 18.

- Grinnell Papers. From a July 7, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a June 10, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From a July 26, 1901, letter.

- The route I favor in the 1931 USGS map descends to the lake in a relatively straight path. This is an interesting map. Note that in 1931, sections of the road up to Crater Lake’s rim were steeper than today. Perhaps the Park Service decided to make the climb gentler to accommodate an increasing number of motor homes and cars towing trailers. Also note the location of a campground near the Lodge. Though long gone, you can still see the campground roads in Google Maps Satellite View. Retrieved Nov 21, 2022.

- Grinnell Papers. From an undated but 1901 post-expedition letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From another undated but 1901 post-expedition letter.

- The National Park Service provided the following information: “The Sinnott Memorial is an impressive stone structure built 50 feet below the caldera rim into a steep rock outcrop called Victor Rock. The structure was dedicated in 1931 as a memorial to Congressman ‘Nick’ Sinnott, who represented the Eastern Oregon Congressional District in the US House of Representatives.” Retrieved Nov 16, 2022.

Regarding Merriam’s involvement: “Merriam believed that intellectual curiosity and the search for meaning in nature should be the focus of public parks as an institution. At Crater Lake National Park, he facilitated the creation of a nature guiding, or ‘interpretation,’ program beginning in 1926. He tapped Carnegie money to augment federal funding for the Sinnott Memorial near the lodge at Rim Village, as an educational device to help visitors contemplate how the beauty of Crater Lake and its setting were the result of the relatively recent cataclysmic eruption of Mount Mazama.” From the Oregon Encyclopedia, retrieved November 16, 2022.

Read more about Merriam’s involvement with the Sinnott Memorial Overlook.

- Grinnell Papers. From an undated but 1901 post-expedition letter.

- Grinnell Papers. From an undated but 1901 post-expedition letter.

- Grinnell Papers. This quote and the one in the previous paragraph are from two different and undated 1901 post-expedition letters.