The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition

by David K. Smith, with major contributions by Professor of Geology Connie Soja, Colgate University

In 1899, Annie Montague Alexander and her good friend Martha Warren Beckwith took a 10-week trip on horseback through northern California and southern Oregon that included a visit to Crater Lake. During the trip, Beckwith piqued Alexander’s interest in geology and paleontology.1 In the fall of 1900, Beckwith encouraged Alexander to join her in auditing one of John C. Merriam‘s paleontology classes at the University of California at Berkeley. The class would stimulate a lifelong fascination with fossils.2

In February of 1901, Merriam invited Alexander to join him and his wife on an expedition to Shasta County but she declined, preferring instead to organize her own independent collecting expedition. In April, Alexander discussed this idea with Merriam and he proposed two possible options: (1) to join a party climbing Mt. Hood and then to meet Merriam later in the John Day region of central Oregon or (2) to take a party to Shasta County in northern California to collect Triassic vertebrate fossils.3 It was the latter option that appealed to Alexander, however, just three weeks later Merriam urged Alexander to consider another plan that would instead take her to Fossil Lake, a desert region in south-central Oregon where large quantities of Quaternary fossils—primarily birds and mammals—had been found.4

Since Alexander would be collecting on behalf of the University, Merriam provided the expertise: Herbert W.F. Furlong, a 29-year-old student who worked as a preparator and field hand for Merriam, and William B. Greeley, a 21-year-old student. An African American fellow named Ernest was hired on as the cook. Since it was improper for a lone woman to travel with a group of men, Alexander invited a teacher friend, Mary E. Wilson (31 years old at the time), to join her on the expedition. Alexander was 33 years old.5

Furlong advised Alexander on all aspects of the trip preparations—wagon, horses, provisions, kitchen gear, etc. It was decided that the expedition would set out from Yreka in northern California so Furlong went up two weeks early to procure the horses. Even before setting out, Alexander fully intended to return from Fossil Lake via Crater Lake, wanting to see it again after her trip there with Martha Beckwith in 1899.6

The five-person crew left Montague, just east of Yreka, on May 30 and headed east across the lower Cascades via Ball Mountain Road (today called Ball Mountain Little Shasta Road). A couple of days out, a 14-year-old boy named Willis somehow attached himself to the Expedition. After crossing Butte Valley, the party turned north, passing east of what is now the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, and spent a couple days in the Merrill, Oregon, area. From there Alexander et al. traveled roughly north to Olene and then followed the route of present day OR-140 through Dairy and across Yainax Ridge. Then it was on through Beatty to Bly, where the Expedition hoped to take a fairly direct route over the mountains to Summer Lake. Unfortunately, snow in the mountains forced it to take a long detour east to Lakeview (still following today’s OR-140). From Lakeview the group traveled north to Clover Flat taking either Cox Creek or Dicks Creek Road over the mountains. From there it went to Paisley where George C. Duncan, the local fossil expert, joined them. Duncan led them around the south and west sides of Summer Lake and over Picture Rock Pass to his own ranch on the west shore of Silver Lake. Duncan took the company up to the fossil beds east of Christmas Valley. Collecting had been going on at Fossil Lake since the late 1870s but there were still fossils in abundance. Alexander estimated that they collected about 300 pounds of fossils.7

Furlong dictated his field notes to Mary Wilson who dutifully entered them into a notebook, however, where those field notes are today is a mystery. They are not in the UCMP Archives, Merriam did not take them with him when he left Berkeley to assume the presidency of the Carnegie Institute in Washington, DC, in 1920, nor are they in the Merriam papers archived at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.8

When through collecting, Furlong and Greeley left the group and rode north to see if they could determine how the John Day fossil beds related to Fossil Lake’s.9 The others returned to Duncan’s ranch to wait for the men. Once reunited, the company set out to look for more fossils at what it referred to as the “Sandstone Ridge,” probably on the west side of today’s Black Hills Area of Critical Environmental Concern. After saying goodbye to George Duncan, Alexander and the others headed for Crater Lake. Before reaching the lake, Greeley received word of a job opportunity so he left the Expedition at Fort Klamath.10 The remaining members of the Expedition reached the rim of the lake via the Dutton Creek valley west of Munson Ridge. The party camped on the rim for several days, hiking, fishing, and boating.

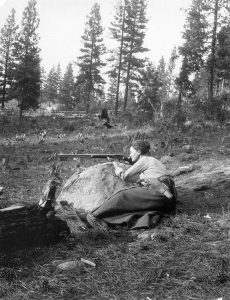

During one hike, Alexander lost a camera over a cliff; fortunately, she brought two. She had bad luck with cameras. The following year, on an expedition to Shasta County, she lost another when a fire swept through camp.11

When it came time to leave, the Expedition backtracked to Fort Klamath and headed south to the northwest end of Upper Klamath Lake. Alexander, Wilson, and Furlong took a steamboat across the lake to Klamath Falls while Ernest and Willis took the wagon and horses on roads around the west side of the lake. Alexander and her crew then followed the Klamath River into California and passed through Ager on their way back to Montague, arriving on August 13, almost 11 weeks after their departure.

The fate of the Fossil Lake fossils

In a November 10 letter to her lifelong friend, Martha Beckwith, Alexander reported:

Our fossils from Fossil L. arrived two weeks ago Thursday and Mary and I spent the afternoon unwrapping them and putting them on trays. They are perfectly free from rock which means a great saving of time and money—I think Dr. Merriam was pleased, especially with the bird bones—there must have been over a hundred perfect ones, small fragile things almost as black and glossy as ebony. They are to be sent to a specialist in Washington who will write a paper on them and then return them.12

It appears that Merriam originally intended to send the bird fossils to Robert Wilson Shufeldt (1850-1934), a prolific author of papers on a variety of subjects, but primarily on birds both extant and fossil. Shufeldt was something of an authority on the Fossil Lake birds, having published two papers on those collected by Edward Drinker Cope and Thomas Condon.13 However, Shufeldt was engaged in something of a scandal at the time14 so Merriam had to find someone else. The following excerpt explains who ended up studying the bird fossils:

The avian remains were first placed by Professor John C. Merriam in the hands of Mr. F.A. Lucas for determination and description. Unfortunately that able student of avian osteology was prevented by the pressure of other duties from giving the collection more than a cursory examination, and after retaining the material for some time he returned it to the University with a purely tentative identification of the various species represented. After the lapse of a number of years, the task is assumed by the present writer ….15

The “present writer” was Loye Holmes Miller (1874-1970) who published a description of Alexander’s Fossil Lake birds in 1911, a year before achieving his Ph.D. A student of Merriam’s, Miller earned his B.A. (1898), M.A.(1904), and Ph.D.(1912) all at the University of California, Berkeley. He later became a professor of zoology at UCLA but published on fossil birds throughout his professional life. Hildegarde Howard, another UC Berkeley graduate, described Miller as “the founder of avian paleontology in California.”16

There are 127 Fossil Lake bird fossils catalogued in the UCMP vertebrate collection, the vast majority of them collected by Alexander and her crew. In contrast, there are 1,430 mammal fossils in the collection.

In June 1902, Alexander reported in a letter to Beckwith that:

A paper is being written just now on our Fossil lake fossils. I haven’t had time to ask much about them but the collection is proving quite interesting there are new species of birds and carnivore among them also a camel and horse.17

So who was working on the mammals? The first decent description of Berkeley’s Fossil Lake mammals was not published until Herbert Oliver Elftman’s work in 1931. Elftman noted that there were three collections of Fossil Lake fossils at that time:

The largest collection, made by Sternberg [Charles Hazelius Sternberg] and Cope [Edward Drinker Cope], is the property of The American Museum of Natural History. The specimens collected by Condon [Thomas Condon] are in the possession of the University of Oregon. The remainder of the known specimens from Fossil Lake are in the Museum of Palaeontology of the University of California. They were collected in part by Miss Alexander in 1901 and in part by Stock [Chester Stock] and Furlong [Eustace Leopold Furlong, brother of Herbert] in the summers of 1923 and 1924.18

Of course, more material has been collected at Fossil Lake since then. An excellent 1966 work on Fossil Lake’s geology and faunas was written by Ira Shimmin Allison. The funding for Allison’s field expenses were provided by none other than the Carnegie Institution of Washington, where Merriam had served as president from 1921 to 1938.19

View a pdf of the 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition scrapbook

Read an analysis of the Fossil Lake Expedition’s route and adventures

Read an analysis of Alexander’s scrapbook photographs

Read about Annie Alexander’s 1905 Saurian Expedition to the Humboldt Mountains of Nevada

A fairly large collection of Alexander correspondence and other related documents are held in the UCMP Archives; see the online finding aid

The expedition participants

MARY ELIZABETH WILSON (1869-1949)

Mary Wilson was born in Helena, Montana, in September 1869 to Enoch Henry Wilson (1829-1890) and Joanna Halsted McIntire (1844-1921). She had one older brother, Arthur B. Wilson (1865-1929). Sometime prior to 1880 it appears that Enoch and Joanna divorced, with Joanna taking Wilson and her brother to Oakland, California. Wilson graduated from Oakland High School in 1887, then headed east to attend Smith College where she became president of her Senior Class. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1892, then returned to Berkeley to earn a Master of Leadership (in Education) degree four years later.

Wilson taught English in San Francisco at Miss Murison’s School (probably where she was at the time of the Fossil Lake Expedition) until the 1906 earthquake, which destroyed the school. She then crossed the Bay to teach at the Anna Head School for Girls at 2538 Channing Way in Berkeley. Moving to the East Bay, Wilson looked after her aging mother until Joanna’s death in 1921. Wilson never married.

When Anna Head retired in 1909, Wilson purchased the school and ran it for 29 years until her own retirement in 1938. The Head School later merged with the Royce School and became today’s Head-Royce School, now in Oakland.

As if running a school wasn’t a big enough challenge, Wilson was involved in many other things. She was a member of:

- The Smith College Society of Northern California (president from 1915-1918)

- The Fortnightly Club (president from 1922-1924)

- The Berkeley Town and Gown Club (president in 1925)

- The Women’s Club of San Francisco

- The National League for Women’s Service in San Francisco

- The Pacific Coast Association of Collegiate Alumnae (vice president from 1912-1915)

- The Young Women’s Christian Association

- The Claremont, Mount Diablo, and Orinda country clubs

- She translated two books on child development and was active in the American Association of University Women and National Association of Principals of Schools for Girls (as president)

- Wilson was awarded an honorary degree — Doctor of Humane Letters — by Smith College in 1931

Wilson died in Oakland on March 5, 1949, one year and nine months before Annie Alexander. That same year a scholarship fund was established in Wilson’s name by Smith College.20

HERBERT WILLIAM FIELD FURLONG (1872-1940)

Herbert Furlong, older brother of Eustace Furlong, was born in San Francisco on March 14, 1872. He moved to Berkeley to attend the university and while a student, became a preparator for John C. Merriam. Furlong participated in at least four of Merriam’s fossil collecting expeditions: two to the John Day fossil beds of central Oregon, one to Fossil Lake in central Oregon, and one to Shasta County.

Furlong graduated from UC Berkeley in 1904. In his junior and senior years at Berkeley, Furlong was a member of both the Winged Helmet, a junior honor society established at UC Berkeley in 1901, and Phi Sigma Delta. He was a member of the Artist Club and served as Secretary and Treasurer of the English Club, the latter being established in 1903.

Outside of paleontology, Furlong had contact with two participants (not counting his brother Eustace) in the 1905 Saurian Expedition while at Berkeley. Malcolm Goddard overlapped with Furlong at Phi Sigma Delta in 1904. The 1903 Blue and Gold Yearbook puts Furlong on the Reception Committee for the Junior Promenade (November 29, 1901) along with Edna Wemple.

A year after graduating, Furlong married Martha Bowen Rice (1881-1974) and they were to have two children, Houghton Field Furlong (1907-1979) and Marjorie Jane Furlong (1908-1983).

Furlong took a job at the Pacific Commercial Museum in San Francisco. The Museum was a “public institution organized for the purpose of facilitating commercial relations among the countries on the Pacific Ocean.” Furlong did not stay at the Pacific Commercial Museum for long. In 1910 he and his family were living in Pleasanton. Ten years later they were living in Oakland where Furlong was an engineer in the agriculture industry. In 1930 the family was back in Berkeley and Furlong was “self-employed.” Shortly thereafter, the family relocated for the last time, settling in Santa Barbara. Furlong died there on August 9, 1940, at the age of 68.21

WILLIAM BUCKHOUT GREELEY (1879-1955)

William Greeley was born on September 6, 1879, in Oswego, New York. Not a lot is known about him. He was living with his family at 1701 Euclid Avenue in Berkeley while he was a student at the university. After college he got into forestry and lumber.

Greeley served in the U.S. Army during WW I, achieving the rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

He married Gertrude Maxwell Jewett (1878-1970) in Berkeley in 1907. They were to have one daughter and three sons. The Greeleys soon moved to Missoula, Montana, but relocated to the Washington, DC, area around 1911. Sometime before 1930 the family returned to the West Coast, settling in Seattle, Washington. Greeley died in Port Gamble, Washington, on November 30, 1955, at the age of 76.22

Sadly, there is no information about the camp cook Ernest, nor the boy Willis, not even their last names.

- Barbara Stein, On Her Own Terms: Annie Montague Alexander and the Rise of Science in the American West, University of California Press, 2001, pp. 16–17. 1899 trip information and Beckwith’s responsibility for Alexander’s interest in geology and paleontology.

- The Joseph and Hilda Wood Grinnell Papers, BANC MSS 73/25 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Box 5, Letters from Annie Montague Alexander to Martha Beckwith 1899-1940 undated. In a Spring 1901 (probably early April) letter to Martha Beckwith, Alexander wrote “I’m taking a course under Dr. Merriam called General Palaeontology …. It really preceeds [sic] the course we took.”

- Grinnell Papers. The first two field options from a letter Alexander wrote to Beckwith in Spring (probably April 10) 1901.

- Grinnell Papers. The Fossil Lake plan from a letter to Beckwith dated May 2, 1901.

- Grinnell Papers. Expedition members Furlong, Greeley, and Mary Wilson are introduced in a May 2, 1901, letter to Martha Beckwith. Alexander first mentions Ernest (she spells his name Earnest) in a letter written from their camp west of Bly, Oregon, on June 10, 1901. Furlong, Greeley, and Wilson ages determined from information found on ancestry.com.

- Grinnell Papers. May 2, 1901, letter to Beckwith.

- Route determined from the Expedition scrapbook in the UCMP Archives and online research (see The Fossil Lake Expedition—Part 1: Route and Adventures).

- Grinnell Papers. Alexander mentions Furlong dictating his field observations to Mary Wilson in a post-expedition 1901 letter to Beckwith.

- Grinnell Papers. From a July 7, 1901, letter to Beckwith written while Alexander was at the Duncan Ranch.

- Grinnell Papers. From a July 26, 1901, letter to Beckwith written while Alexander was at Crater Lake.

- From Katherine Jones’s July 7, 1902, journal entry. See a pdf of her account.

- Grinnell Papers. November 10, 1901, letter.

- See (1) Shufeldt, R.W. 1891. On a Collection of Fossil Birds from the Equus Beds of Oregon. American Naturalist, 24:359–362. (2) Shufeldt, R.W. 1892. A Study of the Fossil Avifauna of the Equus Beds of the Oregon Desert. Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 11:389–425.

- Read about the scandal on Wikipedia. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- From Miller, L.H. 1911. Additions to the Avifauna of the Pleistocene Deposits at Fossil Lake, Oregon. Bulletin of the Dept. of Geology, University of California Publications, 6(4):79-87. The excerpt is from page 80. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

F.A. Lucas was Frederic Augustus Lucas (1852–1929), an American zoologist and paleontologist who served as director of the AMNH from 1911–1923. At the time of the Expedition, Lucas was at the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

- From Howard, H. 1970. In Memoriam: Loye Holmes Miller. The Auk. 88(2): 276–285. The quote is from page 284. Retrieved January 19, 2023. Howard herself published on the Fossil Lake birds: Howard, H. 1946. A Review of the Pleistocene Birds of Fossil Lake, Oregon. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication, 551:143-195.

- Grinnell Papers. June 1, 1902, letter.

- From Elftman, H.O. 1931. Pleistocene Mammals of Fossil Lake, Oregon. American Museum Novitates, No. 481. 21 pp. The excerpted quote is from page 4.

- Allison, I.S. 1966. Fossil Lake, Oregon: Its Geology and Fossil Faunas. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis. 48 pp.

- From resources on ancestry.com and Knapp Architects, Historic Structure Report: Anna Head School, University of California, Berkeley, California, 2008, pp. 59-61.

- From resources on ancestry.com. Quote from Modern Research Society, The Current Encyclopedia: A Monthly Record of Human Progress, Vol. 2. Current Encyclopedia Company, Chicago, 1902, p. 875.

- From resources on ancestry.com.