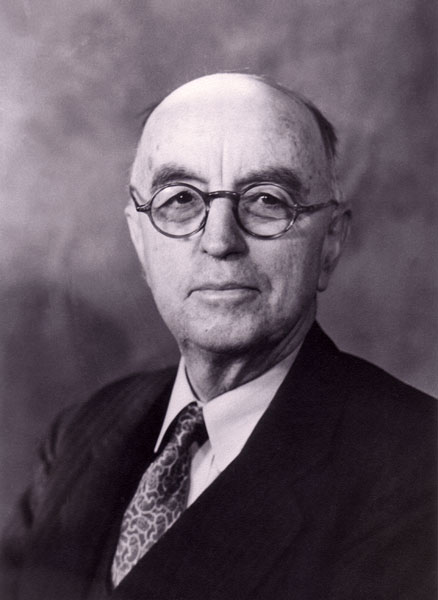

Bruce L. Clark (1880-1945)

First director of UCMP

By Joseph T. Gregory1

In 1920, Professor John C. Merriam suddenly departed from Berkeley to become President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. This led to an uneasy reunion of the remaining paleontological faculty with the Department of Geological Sciences and to the formation of the Museum of Paleontology as a separate unit of the University. There was friction between the paleontologists and other geologists. Professors Chester Stock and John Buwalda left the department to go to Cal Tech in 1926. Miss Annie Alexander was dissatisfied with conditions in Bacon Hall, which was not fireproof. She also objected to the way that Dr. Merriam and his former students were publishing on University collections through the Carnegie Institution rather than the University. During this troubled period, Bruce Clark became the first Director of the Museum of Paleontology in 1921. He provided leadership for the paleontologists and strove to heal the rifts that had developed. However, throughout Clark’s years as director, Merriam continued to be involved (some might say interfere) in the affairs of both the Department of Geological Sciences and UCMP, until Clark had had enough, resigning the position in 1926.

Bruce Lawrence Clark was born in Humboldt, Iowa, on May 29, 1880. From an early age, he worked as a farmhand to support his family. He also taught school from about 1898. When the family moved to southern California in 1904, Clark entered Pomona College and took premedical studies. Proceeding to the University of California, he earned his M.S. in geology in 1909 and Ph.D. in paleontology in 1913. He was appointed Instructor in the newly formed paleontology department in 1911, promoted to Assistant Professor in 1918 and Associate Professor in 1923.

Dr. Clark was a stimulating teacher, full of enthusiasm for his research, and always accessible to students. His classes in invertebrate paleontology emphasized systematics and identification, particularly of Recent and Tertiary forms. Field trips were an important part of his instruction. He attracted many graduate students, some of whom rose to prominent places in the petroleum industry as well as in the academic field. The need for micropaleontologists during the post WW I oil boom led him to arrange for the first courses in this field at Berkeley in 1923. His advanced seminar on “Tertiary History of the West Coast of North America” was held at his home near Cragmont and regularly ended with refreshments provided by Mrs. Clark.

Clark published numerous important studies of invertebrate faunas of the Pacific Coast region, and on the correlation of Tertiary strata of this area with those of Europe and other regions. With Dr. A.S. Campbell he described a series of radiolarian faunas from the California Coast Ranges. Besides his extensive paleontological investigations, he mapped the geology of the Mt. Diablo region, and developed original and controversial theories about the tectonic history of the Coast Ranges. He brought the occurrence of fossil mammals at what is now the Blackhawk Fossil Quarry to the attention of vertebrate paleontologists.

An indefatigable field geologist and fossil collector, Clark built up the Museum collections not only by his own efforts, but also by the acquisition of many important collections from oil companies in the California Coast Ranges, South America, and the East Indies.

From 1937 to 1939 Clark served as chair of the Mount Diablo Museum Advisory Committee, a group composed of university professors and townspeople of Contra Costa and Alameda Counties. The committee was set up to assist artists working on graphic educational material for the as yet unbuilt Mount Diablo Museum. Read more about the fate of these efforts on the Mount Diablo Interpretive Association website.

During the final two years of his life, Clark served on the Committee on Common Problems of Genetics, Paleontology, and Systematics, a group of scientists seeking an improved synthesis between the three fields to achieve a greater understanding of the process of evolution. The activities of this committee led to the founding of the Society for the Study of Evolution in 1946 and the journal Evolution.

Clark died of cancer on September 23, 1945.