The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Appendix

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Part I—Route and Adventures

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Part II—Alexander’s Photographs

Martha Beckwith

Martha Warren Beckwith was born in Massachusetts in 1871. The family moved to Maui, Hawaii, three years later. Beckwith’s father “developed the Haiku Sugar Plantation on Maui that was eventually managed by the large shipping company of Alexander & Baldwin” [i.e., Samuel Thomas Alexander, Annie’s father, and Henry Perrine Baldwin, her uncle]. Beckwith and Alexander became friends as children and remained close throughout adulthood.1

Beckwith graduated from Mount Holyoke College in 1893 and taught English at Elmira, Mount Holyoke, Vassar, and Smith Colleges. In the early 1900s she changed gears, returning to school for a Masters degree in anthropology at Columbia University and a Ph.D in 1918.

“In 1920, Beckwith was appointed to the chair in Folklore at Vassar College, making her the first person to hold a chair in Folklore at any college or university in the United States.” Interestingly, the chair was established by an anonymous donation. The anonymous donor turned out to be Annie Alexander. “Beckwith became a full professor in 1929 and retired in 1938.”2

Beckwith researched and published on folklore, folk tales, culture, and creation myths from places around the world but focused primarily on Hawaii, Jamaica, and the Sioux and Mandan-Hidatsa Native American Reservations in North and South Dakota.

Beckwith died in 1959 and is buried on Maui in the Makawao Cemetery, not far from Annie Alexander’s grave.

Mary Wilson

Mary Elizabeth Wilson was born in Helena, Montana, in 1869 and later moved to Oakland, California, with her mother. She graduated from Oakland High School in 1887, then headed east to attend Smith College where she became president of her Senior Class. She graduated with a bachelor’s degree in 1892, then returned to Berkeley to earn a Master of Leadership (in Education) degree four years later.

Mary taught English in San Francisco at Miss Murison’s School (probably where she was at the time of the Fossil Lake Expedition) until the 1906 earthquake, which destroyed the school. She then crossed the Bay to teach at the Anna Head School for Girls at 2538 Channing Way in Berkeley. Moving to the East Bay, Mary looked after her aging mother until the mother’s death in 1921. Mary never married.

When Anna Head retired in 1909, Mary purchased the school and ran it for 29 years until her own retirement in 1938. The Head School later merged with the Royce School and became today’s Head-Royce School, now in Oakland. Mary was a member of several clubs, societies, and associations.

Mary died in Oakland on March 5, 1949, one year and nine months before Annie Alexander. That same year a scholarship fund was established in Mary’s name by Smith College.3

Montague

Montague is a small Siskiyou County city of 1,226 people located six miles east of I-5 at Yreka.4

I wondered if there was some connection between the town’s name and Annie Montague Alexander. There was none. The town was named after Samuel Skerry Montague (1830-1883), Chief Engineer of the Central Pacific Railroad, responsible for the Sacramento to Promontory, Utah, line of the Transcontinental Railroad.5

Ball Mountain Road and the Tickner extension

A road running east from Montague and over the Cascades to Butte Valley was already present by the early 1860s but it did not go by Edgar Ball’s ranch. Originally, it ran SE from Bull Meadow (see the “Smith’s Ranch/Summit Meadow to Butte Creek” map in Part 1) toward Horsethief Butte and entered Butte Valley near where US-97 does today. It probably didn’t pick up the name Ball Mountain Road until after 1871 when H.C. Tickner, seeing a need for a connecting route between Montague and points east like Alturas, built a road beginning at Bull Meadow and ran it right by Edgar Ball’s Forest Meadows Ranch. Ball Mountain, at 7,775 feet and just NW of Ball’s ranch, was presumably named for Edgar. It was the Tickner road that the Expedition followed to Butte Creek.

With the completion of the Tickner extension, Ball Mountain Road became an important shipping route between Montague and Klamath Falls. For about 30 years the road saw heavy freight and livestock traffic. During the Modoc War of 1872-1873, Montague became a depot for the army fighting at the lava beds (now Lava Beds National Monument) and the Ball Mountain and Tickner Roads were the main supply route.

Ball Mountain Road lost its importance in 1903 when a rail line reached Pokegama in Klamath County, Oregon. Today it looks like just another dusty forest road and little to no evidence of its former glory can be discerned.6

Hughes

The Hughes were probably Edward William Hughes (1861-1907) and his wife Frances Netta “Nettie” Burr Hughes (1852-1930). Edward was the proprietor of a restaurant in Montague but was living east of town near Table Rock. According to a newspaper article Edward Hughes died of a mysterious gunshot wound: “Nothing additional has been learned of the shooting although there are persistent rumors that it was not accidental. One story is to the effect that he was shot twice by a drunken man at a shooting gallery or during a shooting match.” Hughes was 46 years old at the time.7

Edgar Ball and the Forest Meadows Ranch

Edgar Ball was …

… one of the first pioneers to enter the Butte Valley and settle the Forest Meadows Ranch. There was a hotel at the ranch, and cattle drivers from Linkville (now Klamath Falls) would stay overnight there en route to the railroad station in Montague, which they reached via the Ball Mountain Road. The Prather family bought the ranch just after the turn of the century [another source said around 1890] and added a lumber mill and narrow gauge railroad on the property. In the 1930s the ranch changed hands again, this time into the ownership of the Robinson family [Metsker Maps’ 1957 Siskiyou County map8 spells the name Robison]. … In 1964, the ranch was purchased by Ralphs Ranches, whose primary stockholder is Walter Ralph, founder of the grocery store chain. Ralph … opted to keep the name of the ranch Prather Ranch. The ranch consists of 3,000 acres called the Headquarters Ranch, which is where the pastures, pens and new slaughterhouse are located, and another 3,000 acres for hay production.9

The presumed extent of the Ball Ranch was determined using the 1957 map referenced in the above quote. This township and range map indicated the land owned by Robison (or Robinson), the ranch owner at the time the map was made. Of course, it’s possible that Robison (or Prather, the previous owner) sold some of the original ranch land or acquired more since Edgar Ball’s time.

Butte Creek

Butte Creek originates near Ash Creek Butte, NE of Mt. Shasta, and flows roughly north into Butte Valley. By the time the creek reaches today’s East Ball Mountain Little Shasta Road west of Mt. Hebron, it is just a trickle, having been diverted into irrigation ditches along its course.

Boyes Ranch

Charles Babcock Boyes (1844–1890)—sometimes spelled “Boyce”—established a ranch on the Creek in 1870. A 1996 Siskiyou County Land & Resource Development Plan10 reported that the Boyes Ranch later became the property of the Butte Valley Irrigation Company. This company was still indicated as the owner of the land in Metsker Maps’ 1957 township and range county map11 so, like the Edgar Ball Ranch, the extent of the Boyes Ranch could be determined. And yes, it’s possible that some of the original ranch had been sold off or more land acquired.

Davis Ranch

The Van Brimmer brothers, Ben, Dan, and Clint, homesteaded along Willow Creek in 1864 but later sold the land to William Davis and his partner John Bull in 1883. The 2,000-acre ranch was a regular stopping place for drovers driving cattle from Oregon to Montague and for freight teams going north.

Davis sold the stop in 1911 to J.C. Mitchell. It was continued as a stop by Harry Mitchell for several years, then taken over by the Grayson-Owens Packing Co. of Oakland. E.M. Hammond later bought the 2,000 acre ranch to run Hereford cattle.12

So, knowing that E.M. Hammond later purchased what had been the Davis Ranch, the 1957 Metsker Maps Siskiyou County township & range maps13 were helpful in identifying the extent of the ranch.

Laird’s Landing and Lower Klamath Lake

Just four years after the Expedition passed by, Laird’s place became the southern terminus of a steamship line across the lake:

By 1905, a canal had been dredged by J. Frank Merrill from a main channel to the Laird place, and Laird’s Landing was a stopover until 1907. Much freighting was done from Montague, via Ball Mountain, through Red Rock Valley and on around the east side of Lower Klamath Lake into Oregon. Large droves of cattle were taken on this route to be shipped on the railroad to market. Laird’s stopping place was established for the riders with hay for the stock. In 1905, the Klamath, an 80-foot, propeller-driven steamboat owned by the Klamath Lake Navigation Co. ran to a point near the Laird house.14

Although none of the old Landing buildings remain, you can still see the dredged turn-around point on Google Maps Satellite and Terrain Views.

The reason the steamship service only lasted a couple of years is because:

In 1906, Lower Klamath Lake was drained to create 80,000 acres of farmland. There was little thought or concern about how this would hobble migrating waterfowl. A federal reclamation project was established to provide irrigation water for the farmland. The project used water out of the Klamath River that would formerly have flowed as flood water into the Lower Klamath Lake.15

That sounds bad but the story only gets worse. If you’re interested in learning how Lower Klamath Lake has been abused over the years, see the California Waterfowl website (retrieved September 6, 2022).

Merrill and its flour mill

Nathan and Nancy Merrill bought about 160 acres of land between Lost River and Stukel Mountain in 1889. In 1894 they had a surveyor lay out the town. The flour mill near where the Expedition camped was the first building constructed:16

One of the principal crops in the Lost River Valley and Tule Lake Basin was wheat, but it was costly to haul to Klamath Falls. In 1894 the Thomas Martin flour mill was completed. … By 1909, Merrill was known as the “Flour City” because of the large business done by its mill. With a population of nearly 300 people, it was the second largest town in the Klamath Basin.17

The Van Brimmers

As noted in my discussion of the Davis Ranch, the Van Brimmer brothers sold their ranch near Mt. Dome in 1883, then homesteaded east of what would become the town of Merrill. Brothers Dan and Clint had adjoining ranches on Lost River while Ben ended up in Klamath Falls. Due to Ben’s success in creating an irrigation ditch (or ditches), the Van Brimmers became one of the wealthiest and important families in the Merrill area. Their irrigation enterprise was incorporated in 1886 as the Little Klamath Water Ditch Company.18 It is still in operation today as the Van Brimmer Ditch Company.

Alexander’s party crossed over the Van Brimmer Ditch near the Oregon state line (it’s called the Van Brimmer Canal on Google Maps). A good story about the Van Brimmer Ditch can be read on page 13 of Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. Klamath Echoes: Merrill-Keno, No. 7. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR (retrieved August 4, 2022).

Bloomingcamps

George Washington Bloomingcamp (1869–1924) and his brother Edward owned a 1,240-acre stock ranch north of the Sprague River near Bly but they acquired 480 or so acres of land east of OR-39 near Henley in 1899. My map gives an approximate location (I have no idea what the shape of the plot was so I simply made it a square) for the ranch based on this description. I also found an obituary for a woman who was born “at the foot of Stukel Mountain on the Bloomingcamp Ranch.”19

Olene and Dairy

Apparently Olene is not included in census counts so the current population is unknown, but a 1940 source stated that the population that year was 62.20 I would not be surprised to learn that fewer than 30 people call Olene home now. The only business appears to be a small store.

Olene, a Native American word meaning eddy place or place of drift, was named by Captain Oliver Cromwell Applegate in 1884; he was one of the sons of Lindsay Applegate of Applegate Trail fame.

In an online search for the latest population figures for the unincorporated community of Dairy (May 2023), I found four different figures on four different websites: 213, 357, 161, and 152. Despite the discrepancies, the numbers confirm that Dairy is a small town.

As for the “Roberts-Parker contingent” mentioned in the June 7th scrapbook entry, it was William Roberts who chose the name for the town of Dairy. Roberts was the town’s first postmaster, the post office being established in 1876.21

Klamath Indian Reservation

In 1901 the Klamath Indian Reservation covered some 1.2 million acres. Today, all that remains are 12 non-contiguous parcels that total 308 acres.22

Bly and Nellie Bly

Bly, as noted in Oregon Geographic Names, “was a word of the Klamath Indians meaning up or high, presumably up Sprague River from Yainax [a Reservation subagency once located about three miles ESE of today’s town of Sprague River]. The name was appropriated for the town east of the Reservation.”23

Nellie Bly was the pen name of Elizabeth Jane Cochran (1864-1922), a pioneer in the field of investigative journalism. She may be best known for her circumnavigation of the world in 72 days (1889-1890) and her exposé of conditions inside a mental institution (1887) after feigning insanity and being committed.24

Newell’s

George Henry Newell (1855-1943), a farmer, lived in Drews Valley with his wife Harriet Catherine Newell (1860-1938) and six children.25

Lakeview

Lakeview is probably the second largest town the Expedition experienced on the entire trip (Klamath Falls would be the first). It had just rebuilt from a disastrous fire that swept through the downtown area about a year earlier, destroying 64 buildings.

The newspaper serving Lakeview, the Lake County Examiner, regularly listed the names of any visitors (and the nature of their business) that happened to pass through town. Because of the unusual nature of the Fossil Lake Expedition, it received a short article, appearing in the June 20 issue (a week after the Expedition’s Lakeview stay). The title was simply “Fossil Hunters:”

A party of fossil hunters arrived here from Berkley [sic], Cal., last Thursday, and after remaining in Lakeview for a few days started for Sand Springs and Fossil Lake to search for curios and enjoy an outing. The party was well equipped for camping and general outdoor sport and expect to see and procure many things of interest. They intended to stop on their way north at Lone Pine and get the assistance of the mountaineer and “Prehistoric” George C. Duncan as guide to the fossil beds and wonderland of Southeastern Oregon. H.A. Furlong, a graduate of the State University of California heads the party, and he is accompanied by W.B. Greeley of Berkley [sic] and Misses Annie M. Alexander and Mary E. Wilson of Oakland.

From this article we learn that (1) Duncan called his ranch “Lone Pine” (other newspaper articles confirm this) and (2) Duncan was not contacted in advance of the Expedition. Apparently, Duncan’s coming to Paisley was serendipitous (see the June 18 scrapbook entry).

A searchable database of historic Oregon newspapers can be found on the University of Oregon website (retrieved March 21, 2024).

Billing itself as the “Tallest Town in Oregon,” Lakeview sits at 4,757 feet above sea level. In 1900 the population was 761 and as of the 2020 census, 2,418.26

Clover Flat

The area around Clover Flat Road was hit hard by fires in 2020 and 2021. In September 2020, the Brattain Fire burned about 51,000 acres west of the upper half of Clover Flat Road, from Moss Creek NW almost to Summer Lake Hot Springs. In September and October of 2021, the Cougar Peak Fire burned 92,000 acres south and west of the lower half of Clover Flat Road, even jumping the road between Green and Moss Creeks. Although the meadows and pastures of Clover Flat and Moss Creek valley were lush and green at the time of our 2022 retracing, the miles of charred trees on the hills to the west were a stark reminder of these conflagrations.

Bryan Ranch

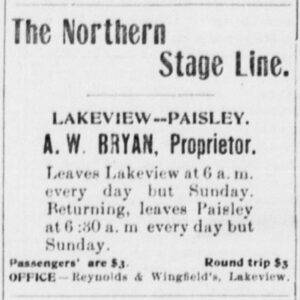

The location of the Bryan Ranch in 1901 eluded me for years. For a long time, the excerpt below was the only information I could find regarding the location of Bryan’s Ranch but it was describing land that Bryan purchased a year after the Expedition passed through:

Ahaz Washington Bryan [with his wife Nancy J. Moss Bryan] resides some 23 miles north of Lakeview at what is known as the Bryan stage station. He is a stage contractor and has been in the business for many years in Lake county. … In 1902, he secured the contract of the mail from Lakeview to Paisley and he has been handling the business ever since. In 1902 he purchased his present home, an estate of 500 acres, one-third of which is first class hay land. He has a good house, large barn, blacksmith shop and various other improvements. … Mr. and Mrs. Bryan keep a stage station for the accommodation of the traveling public and are doing a good business in that line. He also raises cattle and horses.27

The excerpt states that the place Bryan purchased in 1902 was “some 23 miles north of Lakeview” and Valley Falls is almost exactly 23 miles up US-395 from Lakeview. So my working hypothesis was that the Bryan Ranch was near Valley Falls. This was supported by 1900 U.S. Census information that gave Bryan’s location as “Crooked Creek.”28 Although a very vague description, Crooked Creek flows west out of the Warner Mountains, then roughly follows US-395 north for about 13 miles, past Valley Falls to the Chewaucan River. So a Valley Falls location was looking possible.

Then I learned where the ranch that Bryan purchased in 1902 was situated. A 1908 USGS map29 placed it about seven miles to the west of Valley Falls near the south end of Clover Flat, about 23 miles from Lakeview (just like the above excerpt said). Still, this was no help in learning where Bryan was in 1901.

In retracing Alexander’s route in 2022, I learned that four scrapbook photographs—Photos #19, 20, 25, and 26—were taken along Clover Flat Road, which made me start to wonder whether Bryan could have leased the Clover Flat ranch in 1901 prior to buying it. Unfortunately, Photos #21-24, undoubtedly taken at Bryan’s Ranch, have a lot of trees in them and the Clover Flat ranch had few if any trees (Photo #25, a view looking south across Clover Flat confirms this). I could at least make a good guess at how the Expedition reached Clover Flat. The 1908 USGS map I mentioned earlier showed two routes across the mountains from today’s US-395 to Clover Flat that approximate today’s Cox Creek and Dicks Creek Roads. It seems likely that the Expedition took one of them, probably the latter—but where was that 1901 ranch?!

A year and eight months following the retracing, I revisited the problem and I finally found what I was looking for. Searching online, I stumbled upon Bryan’s 1901 ranch location in The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912 (published in 1912) on Google Books:

He [Bryan] … secured a homestead two miles south of his present place [the Clover Flat ranch] in 1887. This he improved and he resided thereon until 1902. It comprised one hundred and sixty acres, which he still owns.

Since 160 acres is one quarter of a section on township and range maps, I looked at Metsker Maps’ 1958 maps for the Clover Flat area and found what I believe to be the quarter section that Bryan lived on for 15 years and where his brother David and mother Mary Jane continued to live.30 And this quarter section has trees on it.

But there are still three lingering problems. The first is the 1900 U.S. Census entry designating “Crooked Creek” as Bryan’s residence. His ranch was quite far from Crooked Creek—it wasn’t even in the Crooked Creek watershed. It was much closer to Clover Flat. The second is the comment by Mary Wilson in her June 17 entry: “Another record broken! We leave camp at eight o’clock and reach Paisley at 4:30 that afternoon.” What record was broken? It couldn’t have been distance since it’s only about 21.5 miles from the 1901-era Bryan Ranch to Paisley. The Expedition covered more ground than that on more than one occasion.

The third problem concerns the photograph order in the scrapbook because at least one appears to be out of place chronologically. If they were placed into the scrapbook in a logical south-to-north order, then the photographs following Photo #18 should have this progression: #21-24, 19, 25 and 26, and then 20. But there is a possible explanation. The Expedition spent two nights at Bryan’s. According to Wilson’s scrapbook entry for June 15, the Expedition arrived at Bryan’s Ranch and spent three hours fishing. On the 16th, for which there is no entry, perhaps Alexander took a ride up Clover Flat Road, taking Photos #19 and 20, and possibly #25 and 26, along the way. Maybe Photos #21-24 were taken back at camp later in the day.

Paisley

The population of Paisley in 1900 was 176 (in 2020 it was 250).

Apparently, Paisley still has a mosquito problem. The town has an annual Mosquito Festival to raise funds for vector control.31 Mosquitoes were a problem for the Expedition along much of its route.

George C. Duncan, his ranch, and the Chewaucan Post

Alexander described Duncan in a letter to Beckwith:

We found old Mr. Duncan here at Silver lake whom every one had been telling us was the man of all men to tell us where the most fossils were to be found, and persuaded him to go with us …. The old gentleman never had any schooling but after he came out here and settled down and the fossil beds were first discovered he took a lively interest in geology and read everything he could find on the subject with a mixture of Spencer, Tyndal and Huxley so his knowledge is a rather disordered collection of facts and ideas. He and his son have a little ranch here on the lake.32

More can be said about George Duncan (1827-1909). He was born in Tennessee, moved to Iowa at the age of 16, married Louise Reinhart there, and crossed the plains to Lane County, Oregon, in 1854. They homesteaded on the west bank of Silver Lake in 1873 and a year later established a Silver Lake post office there; George served as postmaster but the office was discontinued in 1881. George and Louise had five children. Not long after the 1901 Expedition George moved to Harney County, just east of Lake County, but left his 200-acre ranch to his son Felix Dorris Duncan.33

E.A. Emery bought the Duncan Ranch in 1921. Bruce and Penny Emery are the current owners (as of 2023). They are the principal agents of the Royal Crown Cattle Company which has been in business for over 45 years.34

The Chewaucan Post, based in Paisley, was established a little over four months before the Expedition’s arrival.35 Where the newspaper office obtained its fossils is unknown. No doubt the party was expected to do its fishing in the Chewaucan River.

Woodward Hot Springs

Wikipedia claims that the Woodward family homesteaded here in 1902 but it would appear that the date is off by at least one year.36 The springs have seen a few owners over the years; the current owner bought them in 1997.

Fremont Point

Fremont Point is over 7,100 feet above sea level and about 3,000 feet above the surface of Summer Lake. Fremont Point was named in honor of John C. Fremont who coined the names Winter Ridge and Summer Lake when he passed through here in 1843.37

Picture Rock Pass petroglyphs

It’s thought that the petroglyphs are between 7,500 and 12,000 years old.38

Christmas Lake and the Longs

A 1908 USGS paper reported Christmas Lake to be only two or three feet deep and “to be fed by an intermittent spring at its south end.” The paper also noted that “Two years ago there was only one family living in Christmas Lake Valley”;39 that would have to be the homestead of Alonzo Welch Long. The Expedition camped at or near the Long’s place.

Alonzo Welch Long (1848-1919) and his family—wife Mary Jane Wyland Long (1862-1949) and children Everett Rupert (1889-1948), Reuben Aaron “Reub” (1898-1974), and Anna Leland (1899-1992)—moved to Christmas Lake from Lakeview.40 Reub recollects:

By 1900, he [Alonzo] had noticed that the men who got ahead owned land, so we moved to Christmas Lake where he bought a meadow watered by springs. When homesteaders began to crowd him [beginning in 1905], he homesteaded. Our old cabin still stands as this is written, 1962.41

The cabin was built in 1880 with logs hauled in from the Lost Forest, about 20 miles away, NE of Fossil Lake. It’s not clear whether Alonzo built the cabin in preparation to move there or whether someone else built it and subsequently abandoned it. The cabin had three rooms—two bedrooms and one for cooking and dining. The Longs lived at a crossroads and ran an informal inn.42 The cabin remained standing beyond 1963 but an irrigated crop circle now covers the location.

George Duncan and Everett Long are sitting on the cabin’s front step in the scrapbook’s Photo #36. Reub and his sister Anna Long sit on the same step in Photo #46. Reub later moved to the Ft. Rock area and became something of a celebrity in the Christmas Lake Valley. In 1964 he coauthored a book with E.R. Jackman entitled The Oregon Desert. The latest edition, the 14th printing, was published in 2003. Photos #36 & 46 both appeared in the book so Alexander must have sent prints to the Longs after returning to the Bay Area.43

Fossil collecting at Fossil Lake

In a letter to Beckwith, Alexander described the adventure at Fossil Lake:

Well Martha, we have been to Fossil lake and brought out about 300 pounds of fossils. More than we expected after learning how many parties had been in there on the same errand. …

Our collection consisted mostly of Hipparion bones. Besides these were a few camel and elephant bones, rodents and birds. I found over one hundred perfect bones but a good part of them were knee joints of a variety of shapes. They may prove to belong to more animals than we think for but that remains to be seen. The lake proper that is the old bed of a lake that once existed is about ten miles long by two broad. We spent five days collecting, going west the first day, north the next and so on. The fifth day we spent riding about the country outside of the lake limits. The bed for the most part is blown quite free of sand leaving the fossil bones, generally fragments, perfectly exposed, but the best ones I found—a horse’s hoof, teeth, and five bones belonging to the fore leg I dug out of the sand—just enough stuck out to show something was there. It was hard work but exciting, Martha. … The air was cool and clear—not the desert heat we had been expecting. Outside the lake barrier were sage brush and sand dunes and all along the horizon were low lying mountains that broke the monotony.44

The June 27 scrapbook entry reads “Uncle George Duncan comes into camp triumphantly bearing a ‘rhinoceros jaw and tooth’ which upon scientific investigation by the geologists of the party turns out to be a baby elephant’s jaw.” Duncan’s baby elephant jaw is in the UCMP collections database: UCMP specimen 2348, described as a “Right dentary fragment with molar, juvenile” of a mammoth.45 There is no explanation of what the “first disagreement” was about.

The Hardistys

The “Pearl of the Desert” is a reference to Elsie Pearl Hardisty, only daughter of Charles Dodson Hardisty (1847-1923) and his wife Electa Caroline Hardisty (1854-1922). The Hardistys were farmers living in Silver Lake at the time of the Expedition, however, the June 30 scrapbook entry says “We spend the evening at the Hardisty’s” so the family must have been staying near Fossil Lake for some reason, perhaps to water their cattle. Elsie Pearl was around 17 years old in 1901.46 The July 1 scrapbook entry mentions Elsie Pearl again: “Miss Pearl decides to learn Goo Goo Eyes.” The song was a minstrel song, Just Because She Made Dem Goo-Goo Eyes, by John Queen and Hughey Cannon, written in 1900.47

The U.R. Ranch

The U.R. Ranch was located at the intersection of OR-31 and Old Lake Road, NW corner. At the time of the Expedition’s visit, the place was run by Lucinda Halzhauser Egli (1855-1933) and her three sons and three daughters. Lucinda’s husband, Amil, died at the age of 40 in 1893. According to the 1930 census, Lucinda, then 74 years old, was still listed as the head of the household with only one 47-year-old son remaining with her. At some point Lucinda sold the ranch and moved into the town of Silver Lake but when that was is unknown.48 The bench that stretches from Picture Rock Pass down towards Old Lake Road is named Egli Rim after the family.

Logan Butte

The first Logan Butte fossils to find their way into the UCMP collections were collected in the fall of 1900 by L.S. Davis and V.C. Osmont. John Merriam published on some of this material in 1906.49

Price Ranch

“Prices” more than likely refers to the farm of Thomas Bruce Price (1851-1927) and his wife America Evelyn Starr Price (1857-1953). At the time of the Expedition, the Prices lived on Camp Creek, just north of Logan Butte. Apparently, Thomas served as the local postmaster, just as Edgar Ball, Charles Boyes, and William Davis did on their ranches in California and William Roberts and George Duncan did in Oregon. The location of the Price post office was just north of Logan Butte (Google Maps coordinates 43.9665238, -120.3010998).50

Oliver Cromwell Applegate

The Applegate mentioned in the July 18 entry was Oliver Cromwell Applegate (1845-1938), son of the pioneer Lindsay Applegate of Applegate Trail fame. Oliver served five years as United States Indian agent in charge of the Klamath Indian Reservation and was in his third year of that term when Alexander and crew came through.51 I could learn nothing about the fossils that Applegate was presumed to have. As noted under the “Olene and Dairy” entry above, it was Applegate who named the town of Olene.

Annie Spring

Just as I wondered if the town of Montague had a connection to Annie Montague Alexander, I was curious to know if Alexander was the namesake of the creek and spring. No such luck. They were named for Annie Gaines, sister-in-law of Captain William V. Rinehart, the commander of Fort Klamath in 1865 and 1866. The commander, some of his men, and Ms. Gaines climbed from the rim down to Crater Lake, making Annie Gaines the first white woman known to do this.52

Original road to Crater Lake

A lower section of this old road is now part of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). The upper part is the Dutton Creek Trail, an alternative access point to the PCT. According to the Crater Lake Institute, the creek and trail were “named for Captain Clarence E. Dutton who was the chief of the United States Geological Survey group that first took soundings of Crater Lake’s depth in 1886. Also, this trail was originally an old wagon trail used by the park’s first visitors [like Alexander] to reach the rim of Crater Lake.”53 This tells me that the road as drawn on Diller & Patton’s map is over-simplified because the Dutton Creek Trail closely follows the road indicated on the 1931 USGS map.54

Joseph Silas Diller

Diller (1850-1928) is best known for his published work on the geology of Crater Lake, published in 1902, a year after the Fossil Lake Expedition and the year Crater Lake became a National Park.55 Diller was wrong about the Lake having an outlet; current thinking is that water loss is entirely through evaporation and some seepage.56 Alexander would run into Diller again the following year during a Shasta County Expedition.

Diller’s boat

An excerpt from Alexander’s July 26 letter to Beckwith:

We were very fortunate to find Prof. Diller of the U.S. Geological Survey still here when we arrived and now that he is gone are camped on his camping ground. He spent a month here taking sounding and experimenting to discover whether the lake has an outlet. I believe he came to a pretty sure conclusion that it has, after measuring the streams that flow into the lake and estimating the amount of evaporation. He has left us his boat to use till the first when it is to be put under cover for the winter. We have had two sails already ….57

Alexander’s cameras

Alexander told Beckwith in her May 2 letter that she brought two cameras on the Expedition. In her July 26 letter she explains how she lost “her large camera:”

My nerves were not very steady from a foolish walk I had taken the day before down one of the ridges, got into a place where everything was ready to slip from under me and had the shock of seeing my nice big camera that I had set on a rock for an instant, slide away from me and could hear it strike three or four times as it bounded to destruction.58

Philip Bowles, Jr., and Rudolph Schilling

I didn’t expect to find anything about Philip Bowles and Rudolph Schilling but in a June 15, 1901, Oakland Tribune society column I discovered this remarkable entry:

Rudolph Schilling and Phil Bowels [sic] are going to Klamath county in Oregon on a hunting and fishing trip.59

This explains the pair’s reason for being at Crater Lake on July 28. I found out more about the two men on ancestry.com; I even found a photograph of Schilling and Bowles. The 1900 Oakland High School yearbook identifies Schilling as a senior and Bowles—Philip Ernest Bowles, Jr. to be precise—as a junior. Both were members of the Epsilon Chapter of the Phi Sigma fraternity. Bowles Hall on the UC Berkeley campus is named for Philip Jr.’s father, a Cal alumnus, UC Regent, and a former bank president in Oakland.60

Dr. Burnett

Doctor Burnett sounds like he was the senior associate of Schilling and Bowles, Jr.

I don’t know about the Ashland reference but I did find a 39-year-old Dr. Theodore Crete Burnett who taught at UC Berkeley at the time of the Expedition. By 1920 he was an Associate Professor of Physiology.61 He may or may not have been the scrapbook’s Burnett.

George L. Hershberger vs. E.W. Herchberger

One wouldn’t think that there would be many men by the name of Hershberger in the Crater Lake area, but there were two, albeit with slightly different spellings. At first, I thought that the Hershberger in Mary Wilson’s entry lived or used to live near the NW corner of Upper Klamath Lake around today’s Odessa. From what I was able to piece together, he homesteaded there, had a ranch, and built a cabin.62 But he must have become a trapper at some point because that’s how Alexander described him in a letter to Beckwith:

We got the lens back. A trapper went after it for us and I’m going to use it to make enlargements.63

But I found the wrong man. Further research revealed that the homesteader was George L. Hershberger (1860-1933). U.S. General Land Office Records show that 160 acres of land in the Odessa area was issued to George on March 22, 1897.64 Mary Wilson’s Hershberger was actually E.W. Herchberger (note the spelling) and I only found this out after reading Diller & Patton’s Crater Lake paper. Apparently, Diller had engaged Herchberger, whom he too describes as a trapper, to periodically check on lake levels, and the 1902 paper even shows that Herchberger took a measurement on August 1!65 Since he was going down to the lake to take his measurement anyway, E.W. was nice enough to take some time to search for Alexander’s camera.

A few entries in Alaska’s Fairbanks Daily Times mention E.W. Herchberger. In the April 27, 1913, issue there was a listing of activity involving, primarily, real estate and mining claim transactions, entitled “Filed for Record.” The following transaction was filed on Tuesday, April 22: “Deed—E.W. Herchberger, William Buell and Joe Phipps to James Sherard and A.E. Golden. Lucky Lad and Newsboy lode claims, between Little Eldorado and Cleary creeks. Consideration $20,000. Dated October 24, 1913.”66 If this was our E.W. Herchberger, then apparently he went to Alaska to seek his fortune in the gold fields.

The Poplars

Louis Dennis purchased the land from George L. Hershberger, the fellow I mentioned in the discussion of Page 95, and it was Dennis who turned it into a resort. About two months before the Expedition arrived there, Dennis sold the place to B.B. Griffith and he renamed it Odessa. A May 30, 1901, newspaper article reported that:

Louis Dennis who lives near Pelican Bay on Big Klamath Lake has sold his ranch of 480 acres, together with his cattle, horses, steamboat and other personal property to B.B. Griffith of Sumpter, Oregon. The price paid for the whole was $6,000.67

There was a hotel and a dance pavilion at the resort. The former location of the place is marked on Google Maps as the Odessa Resort, Hotel, and Indian Trading Post. Apparently, there was a campground at “The Poplars” and there is still a campground there today, the US Forest Service’s Odessa Campground, just a short walk from the site of the old resort.68

The steamboat and Odessa Creek

As mentioned in the quote in the above entry about “The Poplars,” when Griffith purchased the resort, he also acquired Dennis’s steamboat. It was this steamboat, the Alma, that Alexander, Wilson, and Furlong took across the lake to Klamath Falls. Griffith had just begun regular trips across the lake in early July:

Mr. Griffith’s Steam boat has made its first trip on Saturday from Pelican Bay down the lake to Klamath Falls. We are told that hereafter the boat will make one trip a week during the summer.69

C.H. Schoff captained the Alma. An August 22, 1901, newspaper reported that:

Capt. C.H. Schoff is now making regular Semi-weekly trips from Klamath Falls to Budd Springs, Pelican Bay and the Agency Landing. Boat leaves Klamath Falls on Monday and Thursday at 7 a.m., returning on the following day.

Budd Spring (Camporee Spring) … Fare $1.00 … Round Trip $1.75.70

Alexander took the steamer to Klamath Falls from the resort on Friday, August 9, and though it was 13 days before the newspaper article was printed, that is consistent with the published schedule. Apparently, the names Budd Spring and Camporee Spring were used interchangeably, however, topographic maps place the former just over a hill to the east of the resort and the latter along today’s Odessa Creek. In any case, usage of the spring names are references to the landing at the Odessa resort along Odessa Creek, a channel about a mile long.

Alexander refers to the creek as Budd Spring in a letter to Beckwith:

The picture of Mr. Furlong in the boat was taken at Budd Spring a stream about a mile long [my emphasis] that emptied into Klamath Lake.71

Topsy and Topsy Grade Road

Legend has it that Topsy was named for a prostitute:

During the building of the Topsy Grade …, the crew, some sixty in number, had their camp established at the top of the grade …. Here one day appeared a negro woman and set up her camp and began her business of soliciting the workmen. Her name was Topsy, and jokingly the camp began to be called Topsy’s Camp, and later the Grade and still later the post office also took the name of Topsy.72

Major Watson Overton (1858-1932) made his home near the site of the old camp and it acquired the Topsy name as well:

Topsy was little more than the home and stage stop operated by the Major Watson Overton family at the eastern end of Topsy Grade. The site included a residence and, over time, two schools. Its heyday was in the years 1897 to about 1903 when traffic over Topsy Grade brought freighters and travelers through the area.73

The same H.C. Tickner who built the Ball Mountain Road extension in 1871 [link to anchor for “Ball Mountain Road and the Tickner extension” above] is responsible for much of the original Topsy Grade Road along the Klamath River. He completed it, the first wagon road along the Klamath, in 1875. Both of Tickner’s roads were important routes:

Beginning in March, 1887 [when the railroad reached Montague], the towns of Montague with its Ball Mountain road, and Ager with its Topsy Grade road, became the shipping points for a vast area east of the mountains. This condition lasted until May, 1903, when a branch line railroad was completed to Pokegama in Klamath County. After that, most of the interior traffic transferred there.74

Tickner is not mentioned in the following but it provides a little more information about the Topsy Grade Road:

According to BLM studies, the Topsy Road underwent three construction periods: initial construction from 1874 to 1875 [Tickner’s original road]; a second construction period in 1887 when the grade’s steepness was lessened; and 1890 when Topsy Road and Topsy Grade were cut into a vertical basalt face.

From 1875 to the early 1900s, when the road to Ashland was improved and the railroad reached Klamath Falls via a route east of the river canyon, Topsy Road provided the only year-round access to Klamath Falls and to towns east of the Klamath Basin.75

“Hay Cabin,” i.e., the Way Ranch

The Ways’ place was referred to as the Way Station or Way Ranch.

The Way Ranch served travelers on the Topsy Road. The property included a two story frame house with about eight bedrooms. On the main floor was a men’s parlor and a women’s parlor and a large dining room. Thomas Way worked as a blacksmith to help teamsters and travelers; Mary Way cooked and served meals. … A place to sleep cost $.25 and dinner was $.50. The Ways produced most of the food they served at their stage house.76

Klamath Hot Springs

Richard Beswick (1842-1932) and his wife Margaret Ann Lowden Beswick (1859-1936) originally bought the land (that included the hot springs) for ranching but after having the spring water tested, decided to open a resort. They built a hotel on the south side of the road in 1870 and added a blacksmith shop and barn for stabling horses. The Beswicks sold the hot springs property to Joe and Lile Edson in 1887. The Edsons decided to build a new hotel with 75 guest rooms [an exaggerated claim] on the north side of the road. Guests could avail themselves of a large swimming pool, a covered bath house, six mud baths, a steam bath, and barber shop. Some of the celebrity guests included President Herbert Hoover, author Zane Grey, western movie star William S. Hart, and aviatrix Amelia Earhart. The hotel building burned down in 1915. The property was sold in 1921 and has had several different owners since, including silent film star Margaret Rutherford who held onto it for a very short time.77

McClintock Ranch

William King McClintock (1827-1913) and his wife Jane Elinor George McClintock (1841-1925) homesteaded on the Ager-Beswick Road, across from its intersection with Bullhead Creek Road, in 1881. Their 41-year-old son, George Levans McClintock (1859-1917), also lived on the ranch.78

Ager

According to an historical marker placed by the local chapter of E Clampus Vitus:

With the arrival of the Central Pacific Railroad in 1887, Jerome B. Ager saw a need for a hotel, general store, saloon and dance hall to accompany the existing stage and horse barns. Ager became a railroad staging and freighting hub, providing services and supplies for travelers and local communities. Activities slowed in 1909 with the completion of the railroad line from Weed to Klamath Falls. In 1941 the town of Ager faded away ….79

Today, Ager is really just an intersection of the Ager-Beswick and Ager Roads—there is nothing to suggest that something resembling a town once stood there. The Ager Road takes you the rest of the way to Montague.

- Quote from findagrave.com. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- Quotes from the Beckwith entry in Wikipedia. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- From resources accessed through ancestry.com and Knapp Architects, Historic Structure Report: Anna Head School, University of California, Berkeley, California, 2008, pp. 59-61.

- Information from the Montague entry in Wikipedia. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- Samuel Montague information from resources accessed through ancestry.com and a City of Montague web page. Both retrieved September 3, 2022.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. Klamath Echoes: Merrill-Keno, No. 7. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. Pp. 85-87. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- Information from resources accessed through ancestry.com; the newspaper article was found on findagrave.com. Both retrieved August 3, 2022.

- Historic Map Works. Retrieved August 10, 2022. These maps were produced by Metsker Maps. They provide the names of property owners and indicate property boundaries. The first Metsker Maps store was opened in 1950 by Charles Metsker in Seattle, Washington, and it’s still in business today.

- From a web page entitled Supreme Beef from Northern California. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- Boyes family information from resources accessed through ancestry.com and Siskiyou County Land & Resource Development Plan, Feb 1996, p. 94. All retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Historic Map Works. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Siskiyou County Land & Resource Development Plan, pp. 158–159. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Historic Map Works. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Ibid, p. 160. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- From the California Waterfowl website. Retrieved December 13, 2022.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. P. 33.

- From a web page on Merrill History. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. Pp. 6-7.

- Birth and death information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. The 480 acres figure is from Rose, A.P., R.F. Steele, and A.E. Adams. 1905. An Illustrated History of Central Oregon: Embracing Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Crook, Lake, and Klamath Counties, State of Oregon. Western Historical Publishing Company. P. 1010. This can be read on Google Books. Both retrieved December 27, 2022.

The obituary was from legacy.com. Retrieved June 19, 2023.

- “Compiled by Workers of the Writers’ Program of the Works Projects Administration in the State of Oregon.” 1940. Oregon: End of the Trail, American Guide Series. Binfords & Mort, Portland. 549 pp. The Olene entry is on page 440.

- Source of the Olene and Dairy names from McArthur, L.L. 1974. Oregon Place Names. Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR. 835 pp. The book was originally published in 1928 and an eighth edition is in the works; the most recent edition came out in 2003.

- 1.2-million-acre figure from Hatcher, W., et al. 2017. Klamath Tribes—Managing their Homeland Forests in Partnership with the USDA Forest Service. Journal of Forestry 115(5):447-455. 308-acre figure from the Klamath Tribes entry on Wikipedia. Both retrieved August 7, 2022.

- McArthur. 1974. “Bly” entry.

- Read more about Ms. Bly on Wikipedia. Retrieved Dec 17, 2022.

- Newell family information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- Rose, et al. 1905. P. 848. Population information from the Lakeview entry on Wikipedia.

- Rose, et al. 1905. P. 880. A deed posted on ancestry.com shows that land in Lake County, presumably the Clover Flat parcel, was turned over to Ahaz Bryan by Lewis and Mary Green on May 5, 1902, so there’s no disputing that the purchase was in 1902.

- 1900 census information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- Waring, G.A. 1908. Geology and Water Resources of a Portion of South-Central Oregon. Water Supply Paper 220. U.S. Geological Survey, Government Printing Office, Washington. The map, entitled Reconnaissance Geologic Map of South-Central Oregon, was in a pocket at the back of the publication. In the online version the map is on page 60. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- The Google Books excerpt is from Gaston, Joseph. 1912. The Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912, Volume 4. S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, Chicago. Page 1034, column one. The information about Bryan’s brother David and their mother is from the same source, pages 1033-1034. Ahaz and/or David continued to purchase adjacent properties for both ranches over the years. When David Morgan Bryan died in 1943, the southern ranch had grown to some 3,000 acres (August 14, 1943, issue of the Herald and News, Klamath Falls). The Metsker Maps are found on Historic Map Works. I am guessing that Bryan’s 1901 160-acre ranch was the NE ¼ of Section 20, T.36S., R.20E.

- From the Paisley entry on Wikipedia. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- The Joseph and Hilda Wood Grinnell Papers, BANC MSS 73/25 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Box 5, Letters from Annie Montague Alexander to Martha Beckwith 1899-1940 undated. Quote from a June 7, 1901, letter.

- Duncan information from Rose, et al., pp. 854 and 919. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

- From a Klamath Falls Herald and News article and an opencorporates.com web page. Both retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Lockley, F. 1923. Impressions and Observations of the Journal Man. Oregon Journal. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- From the Summer Lake Hot Springs entry on Wikipedia. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Fremont Point elevation from the US Forest Service and Summer Lake surface elevation from the Summer Lake entry on Wikipedia. Both retrieved August 8, 2022.

- From the Picture Rock Pass Petroglyphs entry on Wikipedia. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Waring, G.A. 1908.

- Long family information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Jackman, E.R., and R. Long. 1964. The Oregon Desert. Caxton Press. P. 32. Portions of the book can be read on Google Books. Both retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Ibid. Pages 19, 20, 32, and 34.

- Ibid.

- Grinnell Papers. July 7, 1901, letter.

- See the record in the UCMP Collections Database. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Hardisty family information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- See The Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection. Retrieved August 10, 2022.

- Waring. Map on page 60. Also, resources accessed through ancestry.com (retrieved August 10, 2022) and a shared personal communication, a June 2, 2022, email from Elaine Condon to Connie Soja.

- Merriam, J.C. 1906. Carnivora from the Tertiary Formations of the John Day Region. Bulletin of the Department of Geology, University of California Publications 55(1):1-64. The paper can be read on Google Books. (Retrieved December 27, 2022). The paper illustrates UCMP vertebrate specimens 1681, 1692, and 9999. Read a short bio of V.C. Osmont—scroll to the subhead “VANCE CRAIGMILES OSMONT (1874-1943)” on UCMP’s page about the 1902 Shasta County Expedition.

- Price information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Post office location from oregon.hometown locator.com. Both retrieved June 9, 2023.

- From the Oliver Cromwell Applegate entry on Wikipedia. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- Annie Gaines information from craterlakeinstitute.com. Rinehart information from Wikipedia. Both retrieved December 21, 2022.

- Crater Lake Institute, Dutton Creek Trail description. Retrieved January 10, 2023.

- See the 1931 USGS map at atlasofplaces.com. Retrieved January 10, 2023 (NOTE: This site was not reachable when tried on March 4, 2025).

- From resources accessed through ancestry.com (retrieved August 14, 2022) and Diller & Patton, 1902.

- From a National Park Service web page on crater lakes. Retrieved August 14, 2022.

- Grinnell Papers. July 26, 1901, letter.

- Ibid.

- “Society Young Men Will Sojourn in the Country,” Oakland Tribune, June 15, 1901, p. 6, columns 4-5.

- Schilling and Bowles, Jr., information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Bowles Hall information from the Bowles Hall entry on Wikipedia. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

- Burnett information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved December 27, 2022.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1965. Klamath Echoes: Boating. Vol. 1, No. 2. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. Pp. 68–69, 81–82. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Grinnell Papers. “Fall 1901” letter.

- Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- Diller & Patton, 1902. Herchberger is first mentioned—”Mr. E.W. Herchberger, a trapper …”—on page 53. Herchberger’s lake measurements are shown in a table on page 55.

- From a search for “Herchberger” on newspapers.com. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1965. P. 31.

- Klamath County Historical Society, 1965. Pp. 68–69, 81–82. Campground information from U.S. Forest Service, Odessa Campground. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1965. P. 31. The steamer Alma had a long career on Upper Klamath Lake and operated under at least four different names. Aside from carrying passengers, over the years it brought “down log rafts, barge loads of lumber, and barge loads of wood, returning with hay, supplies, logging equipment and sawmill machinery.”

- Ibid. On page 29 there is a photograph of the Alma at the Odessa landing.

- Grinnell Papers. A 1901 post-expedition letter written after Alexander had sent some photographs to Beckwith.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1977. Klamath Echoes: Klamath Basin, No. 15. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. P. 86. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- Beckham, S.D. 2006. Historical Landscape Overview of the Upper Klamath River Canyon of Oregon and California. Cultural Resource Series No. 13. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Portland. Pp. 100–101.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. P. 87.

- From the online, August 16, 2022, edition of the Klamath Falls Herald and News. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- Beckham. P. 105.

- Beswick family information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Read a full history of Klamath Hot Springs online: Klamath County Historical Society. 1977. Klamath Echoes: Klamath Basin, No. 15. Pp. 74-82. See a nice collection of Klamath Hot Springs photographs, postcards, and advertisements. All retrieved August 16, 2022.

- McClintock information from resources accessed through ancestry.com. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- NoeHill Travels in California, Historic Sites and Points of Interest in Siskiyou County, Ager Stage Stop. Retrieved December 10, 2022.