The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Route and Adventures

by David K. Smith, with major contributions by Connie Soja, Emerita Professor of Geology, Colgate University

For an analysis of the Expedition’s photographs, see

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Part II—Alexander’s Photographs

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition: Appendix

NOTE: Clicking on the blue text links to more information in the Appendix.

The 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition was Annie Montague Alexander‘s first major fossil-collecting venture on behalf of UC Berkeley’s Department of Geology (there was no Department of Paleontology until 1909). During the Expedition, Alexander took many photographs, some 120 of them being placed into a scrapbook that now resides in the archives of the University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

My interest in the 1901 Fossil Lake Expedition began in 2018. In April of that year, Connie Soja—now Emerita Professor of Geology, Colgate University—contacted Mark Goodwin—now Emeritus Assistant Director for Research and Collections at UCMP—regarding any materials we might have relating to the Expedition. Mark forwarded Connie’s email to me (I’ve been the de facto archivist for the museum since I retired in 2015). Knowing we had the Fossil Lake scrapbook, I was inspired to scan the scrapbook’s photographs and transcribe the text entries—see the resulting online pdf version. I found Alexander’s adventure fascinating and wanted to know more.

Connie already knew much about the Expedition and we began a collaboration to put together a richer, more detailed account of the trip. It was Connie who discovered that The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley had a collection of Annie Alexander’s correspondence1 with her friend Martha Beckwith full of information about the Expedition. Connie visited The Bancroft in May of 2018, transcribed the relevant letters, and generously shared them with me. We have continued to share new theories and discoveries ever since.

The scrapbook in the UCMP Archives and the letters from Alexander to Martha Beckwith remain the two best sources of information about the Expedition.

About the scrapbook

No one knows how the Fossil Lake Expedition scrapbook came to UCMP, but it and the scrapbook Alexander put together for the 1905 Saurian Expedition were probably given to the museum when Alexander died in 1950.

Alexander’s female companion on the trip was Mary Elizabeth Wilson. Since the first line written in the scrapbook is “Notes by Mary Wilson,” I assumed that Wilson made all the text entries. Connie Soja wanted to be certain so she obtained samples of Wilson’s handwriting from the Head-Royce School (Mary ran the school from 1909-1938) and compared them with the handwritten text in the scrapbook—they matched. As it turned out, the only text written in a different hand was “Notes by Mary Wilson,” which compared favorably with samples of Alexander’s handwriting.

Alexander likely took all of the photographs. She brought two cameras with her and there is nothing to suggest that any of the other Expedition members did so. Alexander had at least three sets of prints made—one went to Martha Beckwith and one to John C. Merriam.2 One set ended up in the scrapbook. It’s possible that Wilson put together the scrapbook, either at Alexander’s request or maybe as a gift. It’s also possible that Annie and Mary worked on the scrapbook together.

In this analysis I have included only those scrapbook entries that shed light on the route, camp locations, or make reference to some adventure. The entries, as well as the excerpts from Alexander’s letters, are unedited. Within these, editorial comments made by Connie Soja and/or myself are in brackets.

• • • • •

Expedition origins

Beckwith convinced Alexander to audit one of John C. Merriam’s paleontology classes with her in the fall of 1900.3 Annie was instantly captivated. She wrote to Beckwith afterwards:

What a fever the study of Old Earth that you thought should be a part of my education has set up in me! I really am alarmed. If it were a general interest in geology, there might be something quite wholesome in it but it seems to centralize on fossils, fossils! And I am beleaguered.4

I don’t know if Merriam was aware of the Alexander family’s wealth or if Alexander approached Merriam with an offer to help fund his field work but, in the same letter, Annie mentioned an invitation from Merriam to join him and his wife on an expedition to Shasta County:

I shall probably come back the end of May [from Hawaii] and if there is nothing to prevent will go up to Shasta Co. for a month to hunt Shastosaurus remains. Dr. Merriam kindly asked me to go with him and his wife but their time of going is uncertain and besides, it is better for me to be independent. I could get up a small party and he could direct us.5

Plans for the summer continued to evolve. In early spring, Alexander notified Merriam that she was interested in working more independently so the two met in early April to discuss some possibilities:

He had two plans to suggest …. One was that I join a party of the Mazambas Club who were going to climb Mt. Hood and afterward meet him, Prof. Merriam, in the John Day region. The other plan was that I get up my own party and go with Prof. Smith of Stanford [James Perrin Smith; see The Saurian Expedition of 1905 participants (Retrieved January 21, 2025)] to his hunting ground in Shasta County where he has made some interesting discoveries of ammonites and is already hard at work on a volume on the subject. It is the only part of the whole Pacific slope where the Triassic period can be studied. Prof. Smith found some bones that he sent to Prof. Merriam to study and they proved to belong to the earliest reptilian—the article on the subject however was laughed at by the European scientists for no remains of the kind had ever been discovered in this country. So you see Prof. Merriam is crazy to get hold of some more and verify his statements.6

It was the latter option that appealed to Alexander, however, less than a week later Merriam urged her to consider another plan:

I saw Prof. Merriam the following Monday and he was full of enthusiasm over another plan, which were we able to carry out would mean a good deal more to the University than devoting our time to the Shasta region and that was that we should go to Fossil Lake—Christmas Lake it is on the map—it lies about eighty miles N.E. of Crater Lake. The fossils there are of a later period, Quaternary and are mainly those of the mammoths horse camels and sloth—a collection of fossils found in the region lying between this and the John Day River has just been bought by the university, and if we add to it what we expect to find Prof. Merriam thinks Eastern scientists will have to come out this way to study—But one geologist to his knowing has been to Fossil lake and he stayed there about three days and brought out about a ton of fossils! So there is hopes of our finding something—

There is something too to be determined about the strata which seems very important which I don’t understand. It seems the fossils we expect to find will be seen sticking here and there out of the sand and will not have to be dug out of solid rock.7

Alexander approved of this plan so Merriam selected a couple men to provide the expertise and muscle. These were Herbert W.F. Furlong, a 29-year-old student with field experience who worked as a preparator for Merriam, and William B. Greeley, a 21-year-old student. Annie was 33 at the time.

Expedition planning & departure

Alexander described some of the planning and preparations for the expedition:

The first question we had to settle was where we should start from. I, somehow, wanted to go from Redding following the Fall River to Fall River Mills and thence across Modoc Co. and past Goose Lake to Lakeview, but when we came to calculate the distance we found it would take too much time so we decided upon Yreka in Siskiyou Co. you remember that barren-looking country with cones scattered over it soon after we left Mt. Shasta? From there to Klamath Falls it is about 75 miles and from there to Christmas lake about 175 if we don’t go by way of Lake View. …

Mr. Furlong is proving a treasure. I had no idea there would be so many things to think of in a trip of this kind—He brought down Wednesday lists of things under different headings—kitchen utensils—provisions—transportation etc. and yesterday we spent the whole morning in the city running around looking at things and getting prices. The most important thing of all was the wagon. We wanted one that would carry at least 2000 lbs and decided upon a farmer’s wagon to be covered over with canvas like a prairie wagon. There will be one seat where the driver and one of us can sit. The other three will ride horseback. Mr. Furlong will go up two weeks before we start to hunt up ponies and three strong horses to haul the wagon. The third horse will be one that can be used as a pack-animal if we go off on any side trips. The driver will look after the horses and do the cooking. We shall have a nice little stove …. Wallace [Annie’s brother] has a gun he will let us have so our larder will be replenished with duck grouse and black tail rabbits but we shall carry plenty of provisions so as to set a good table. …

Mr. Furlong will have a box made in which the different kitchen utensils will fit as compactly as possible. He is making out a list of the provisions and the quantity we shall need and will be in Friday to talk things over again. Nearly everything will go on ahead to Yreka as slow freight [including the wagon, presumably] so that when we leave here probably the 29th of May [a Wednesday] everything will be in readiness for us to start right out [in Alexander’s next letter she says that they are leaving “Tuesday evening” so it looks like they left Oakland on the 28th].8

Since it was considered improper for a single woman to travel alone with men, Alexander chose a companion:

I’ve asked Mary Wilson to go with us [Wilson was 31 at the time]. … She teaches in the city but comes home every day—is a strong self reliant person and I’m quite confident will help me to entertain the young men.9

Alexander discussed a proposed return route with Beckwith:

When we have had all we wanted of Fossil lake we shall cross over and strike a road to Crater lake for I must take some good pictures of that lake seeing we shall be so near and I shall have my two cameras with me—then we shall come down the west side of Klamath lake and do some lake fishing. From there we haven’t decided what we shall do—perhaps come down the west side of Tule lake, explore those mountains that looked so lovely and mysterious to us on our long ride to Tule lake—if we have time we may keep on going south till we strike Shasta Co. and do some chizeling in the rocks there after Triassic reptiles.10

Alexander, Wilson, and Greeley must have left Oakland by train the evening of May 28, with the train taking a short “cruise” across the Carquinez Strait from Port Costa to Benicia aboard the train ferry Solano.11 They joined Furlong at the Montague12 station, about three miles east of Yreka, and set out from there mid-afternoon of Thursday the 30th. A fifth member of the group was an African American gentleman named Ernest who was retained to do the cooking but it’s unknown whether he was recruited in the Bay Area or in the Yreka-Montague area.

In the scrapbook, Mary Wilson was very good about mentioning the towns that they passed through and the places where they stopped each night but she rarely said anything about the routes taken to reach them. Naturally, the roads in 1901 were different from today’s and they did not necessarily follow modern routes. Old maps were very helpful in establishing the most likely routes taken by the Expedition but in some cases I’ve had to make best guesses based on what evidence I could scrape together. Adding to the difficulty, Wilson’s entries are filled with several inscrutable insider references that only an Expedition participant would understand.

Route, camps, and adventures

Excerpts from the scrapbook appear below in gray italics and all begin with a date.

Montague to Hughes’

Some of the text along the left edge of the first two pages of the scrapbook has been lost so I’ve made guesses as to what’s missing (in brackets).

[May] 30. We leave … [Monta]gue at 4 P.M. … [after] having exploded … [?]rst grand idea. … [Eleve]n miles to Hughes’ … [Ranch] where we camp … [by the] bank of the … [Little] Shasta River

The five members of the Expedition—Annie Alexander, Mary Wilson, Herbert Furlong, William Greeley, and Ernest—left Montague at 4:00 PM. From this sketchy scrapbook entry, we know that they headed due east along today’s Ball Mountain Little Shasta Road—at the time it was called simply Ball Mountain Road. Although the road shoots straight across the Little Shasta valley from Montague to the western foot of the Cascades, the southernmost extent of the range, a 1905 map of Siskiyou County shows that the main road13 (see the map below) swung south on what is now called Lower Little Shasta Road. Assuming that the party took this route, it would have passed the Little Shasta Church, built in 1878 and still there today. Alexander and crew returned to Ball Mountain Road about 9.7 miles from town.

The scrapbook entry says that the group made “… n miles to Hughes’.” That “n” could be the end of seven, ten, eleven, or any of the teens. The exact location of the Hughes residence is not known but according to the 1900 U.S. Census, it was near Table Rock. Today, the first habitable plot along Ball Mountain Little Shasta Road near Table Rock (following the route I believe the Expedition took) is 11.6 miles from the center of Montague and on the above map I’ve arbitrarily placed the Hughes home there.

Hughes’ to Smith’s Ranch/Summit Meadow

[Ma]y 31. Mr. Bryan … [helps] us up the grade … [and he] informs us that … [“The ?]ircumbulence of the …[?] in the mountaineous … [distr]icts is very great.” … [So we] camp at Smith’s … [Ran]ch. Summit Mead[ow](?) — … [we are] near a large … [sa]w mill.

Mr. Bryan was apparently a teamster, using his horses to help the Expedition get its wagon up the Ball Mountain Road grade into the Cascades. Online research yielded no reference to any Bryan or Smith in the area. Historically, two or three sawmills once operated along Ball Mountain Road. The one Wilson refers to in her entry may have been the last one still in operation but I was unable to discover its location. Two contenders for Smith’s Ranch/Summit Meadow can be seen on Google Maps Satellite View; the photograph accompanying the May 31 entry was probably taken at one of them. The westernmost meadow was explored during my July 2022 retracing of the route and, as it turns out, NNE of the meadow is Smith Spring—perhaps named for the Smith of Smith’s Ranch? In any case, I’ve selected this meadow as the probable location of Alexander’s May 31 camp.

Smith’s Ranch/Summit Meadow to Butte Creek

June 1. Our second day in the mountains. We lunch at Forest Meadows and go on to Butte Creek in the afternoon.

Forest Meadows was the name of Edgar Ball’s ranch, located on the eastern slope of the Cascades and western edge of Butte Valley. The ranch location is indicated on Denny’s 1905 Siskiyou County map. After having lunch there, Alexander followed the Tickner Road (over a portion that no longer exists today) roughly SE across Butte Valley to camp along Butte Creek, just south of the Boyes Ranch and NE of Jerome Butte.

June 2. Sunday at Butte Creek. We visit the “Ice Caves”, having first decided to call our fourth saddle horse “Child of Satan.”

From the Expedition’s camp on Butte Creek, the road continued NE across a plain dotted with volcanic rubble and the fissured faces of three successive lava flows before aligning with a stretch of today’s Red Rock Road.

In what was probably Alexander’s first letter written to Beckwith on the road, she mentioned the ice caves:

Last Sunday we spent just over the range in Siskiyou Co. N.E. of Mt. Shasta. It was a sage brush plain enclosed by mountains. There were two or three old lava flows across it and in one of these were ice caves that we visited. The ice hung in stalactites from the roof and covered the floor and it was all we could do to keep our footing. We would have shot down a depth of twenty feet or more had we slipped so I was glad when we had all scrambled out again.14

In studying the Expedition’s route across Butte Valley and considering Alexander’s comment about “two or three old lava flows,” I gave the satellite views of the area a close look. From above, I saw three volcanic ridges that, on close examination, do have fissures and, apparently, some caves. In 3D, they appear to be the forward faces of three vast sheet lava flows, one on top of the other, the one farthest east being the lowest and oldest in the sequence. A wagon could descend the faces of the western and eastern flows fairly easily, however, the central one is another matter. There are few places along it where a wheeled vehicle can get through and I can find no such place along the route of the Tickner Road. How the Expedition crossed this expanse remains something of a mystery. Finding the caves that the party visited would require some on-the-ground exploration and/or conversations with the locals.

Regarding the “Child of Satan,” in a June 10, 1901, letter to Beckwith, Alexander wrote:

Mr. Furlong was bucked off his horse that morning and has not cared to ride the Child of Satan as he calls him since and we have had a dreadful time leading him.15

Butte Creek to the Davis Ranch

June 3. Lunched at Runaway Lake. Don and Mike get away and Willis goes back for them. We camp at Davis Ranch. Heavy frost at night.

Based on one of Alexander’s letters, I think that Runaway Lake is a name of the Expedition’s invention, so called because that’s where two of its horses escaped:

But our greatest misfortune so far was the losing of our two best riding horses with their saddles. It happened the day after our visit to the ice caves while we were lunching on the border of a little lake in the midst of a plain. One of the horses pulled up his sage brush picket and ran like a thing possessed Miss Wilson’s horse at his heels. We sent Willis, a nice little fellow of fourteen who had joined our party, after them but he soon came back as his horse was on his bad behavior and reported that the saddle had turned on Mike [one of the horses] and he was going like the wind the other horse still following him. So we found a little Indian boy to help him and started them off—that was the last we have seen of Willis—it will be a week tomorrow. There is no telephone or telegraph in this country and for aught we know the legion of foul fiends may still be urging our horses on.16

Mary Wilson’s scrapbook entry is the first to mention the boy, Willis, and Alexander’s letter provides what little information we have on him. It’s not clear when and where Willis joined the party (while camped at Butte Creek perhaps?), or why he was allowed to join it in the first place. Maybe he was recruited to tend to the horses, but if so, he didn’t do a very good job because they often ran off.

The “little lake in the midst of a plain” that Alexander mentions is something of a mystery. Russell Lake is about 1.5 miles south of Red Rock Road and a little farther east is Deyarmie Lake, just under a mile south of the road. It is likely that Annie’s party followed the route of today’s Red Rock Road to ‘Willow Creek and Red Rock Road’ so would they go out of their way to lunch by one of these lakes? North of Russell Lake and just south of Red Rock Road there are what appear to be residual sediments or precipitates (seen in Google Maps Satellite View) from intermittent bodies of water. Maybe there was “a little lake” there in 1901.

Once the Expedition hit what is today called Red Rock Road, it was on segments of major emigrant trails as far as the southern tip of Lower Klamath Lake. Red Rock and ‘Willow Creek and Red Rock’ Roads follow the route of the old Yreka Trail and Lower Klamath Lake/Dorris Brownell Road roughly follows that of the Applegate Trail.17

The Davis Ranch was located along Willow Creek west of Mount Dome. Like Edgar Ball’s ranch, its general location is indicated on Denny’s 1905 Siskiyou County map.18

Davis Ranch to Merrill

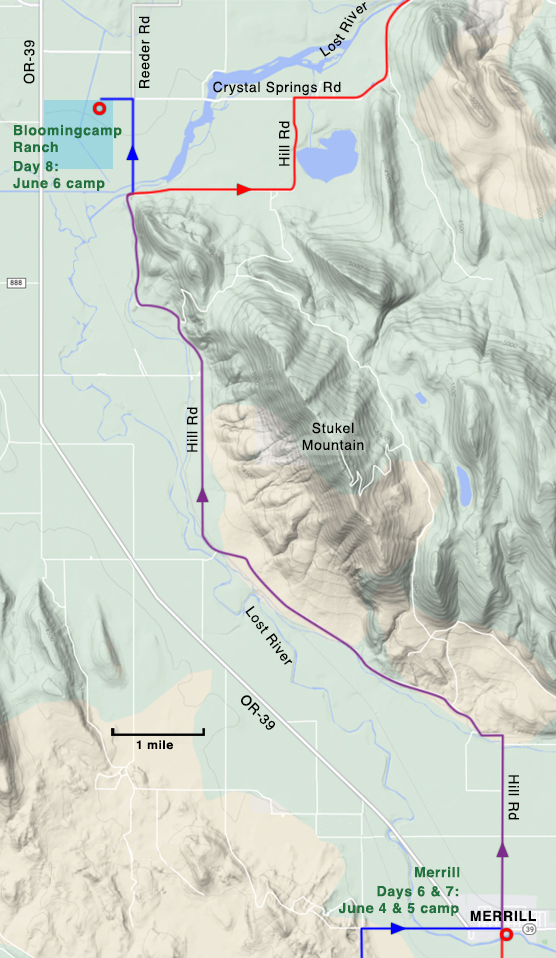

June 4. We drive twenty three miles to Merrill and camp by the flour mill. On the way we narrowly escape being bogged!

About four miles beyond the Davis Ranch, Alexander and crew passed the home of Charlie Laird at the southern tip of Lower Klamath Lake.

Wilson’s entry states that they traveled 23 miles from the Davis Ranch to Merrill. Going by the route I originally thought the Expedition took, the distance from the existing Ranch’s driveway to the flour mill in Merrill is about 19.25 miles. This excerpt from one of Alexander’s letters provides an explanation for the discrepancy:

Tuesday we reached Merrill skirting Lower Klamath Lake for a number of miles. It is a very pretty lake you look over tules at the border …. We came in [to Merrill] from the west.19

I assumed that Alexander took the most direct route to Merrill, approximating today’s Lower Klamath Lake/Dorris Brownell Road and entering the town from the south. But Alexander says that she hugged the eastern shore of the lake. Wilson wrote “narrowly escaped being bogged” suggesting that the road did run close to the lake’s shoreline. As it happens, the road Alexander chose is shown on Denny’s 1905 Siskiyou County map. Not much of it remains today.

On June 4, the party camped near Merrill‘s flour mill. From my research, I believe that the mill was located at the SE corner of the intersection of today’s South Main Street and OR-39, on the banks of Lost River.

June 5. Mr. Greeley starts alone for fossil beds. We spend the morning in scheming to get a bath at the “hotel”, and the afternoon in hunting for fossils. We visit Mrs. Van Brimmer who has already given us the best of her collection and who is now invited to give us all a drink of milk.

This entry says that the party received fossils from the Van Brimmers and that it went out looking for more. This is not surprising since fossils had been discovered while excavating local irrigation ditches:

It is related as an interesting fact that the Van Brimmers, … , in constructing their canal, … , unearthed what was believed to have been a very ancient burial ground. These pioneers were not interested in what a geologist would have gloated over. J. Frank Adams did, however, preserve one specimen—the ankle bone of a horse, petrified, and dug out twenty feet below the surface. Water was what the early ditch builders wanted, not bones. Was a time on the Klamath, some thousands of years since, when the three-toed horse galloped over the plains of central Oregon and the great Klamath country.20

Alexander wrote to Beckwith about their time in Merrill:

We camped two days by the river next the flour mill. It wasn’t a pretty camping place and there were a lot of wood ticks but we had an interesting time tramping around hunting for fossils although we did not find any except fragments but we got quite a little collection from the people in the neighborhood principally horse teeth Hipparion.21

To my knowledge, none of the fossils acquired in Merrill ended up in UCMP’s vertebrate collection, probably due to a lack of provenance, but they could have gone into the teaching collection.

Merrill to the Bloomingcamp Ranch

June 6. We leave Merrill at 3 P.M., having visited the Hills and the Kennedys in the morning, securing a tooth from the former and a bone from the latter. We camp at Blooming camp’s Ranch, the “Child of Satan” escaping just before we reach there.

I could learn nothing about the Hills or the Kennedys, but there was a Bloomingcamp Ranch (spelled with no breaks). It was an approximately 0.75-square-mile plot located east of today’s OR-39 where the Henley school system is located.22

Bloomingcamp Ranch to Dairy

June 7. We reach Olene with wagon, two horses and three people, Ernest having to lead “Child of Satan.” We find Mr. Greeley waiting for us with our first letters from home. We lunch at Olene (4 P.M.) and camp at Dairy, completing our first hundred miles. We call on the Roberts-Parker contingent and learn their whole family history.

I could find no decent map of lower Klamath County older than 1960 so it’s not clear what route the Expedition took from the Bloomingcamp Ranch to Olene. Both Reeder Road and Crystal Springs Road were present in 1960 but whether they were there in 1901, I don’t know.

Today, both Olene and Dairy are unincorporated communities with small populations.

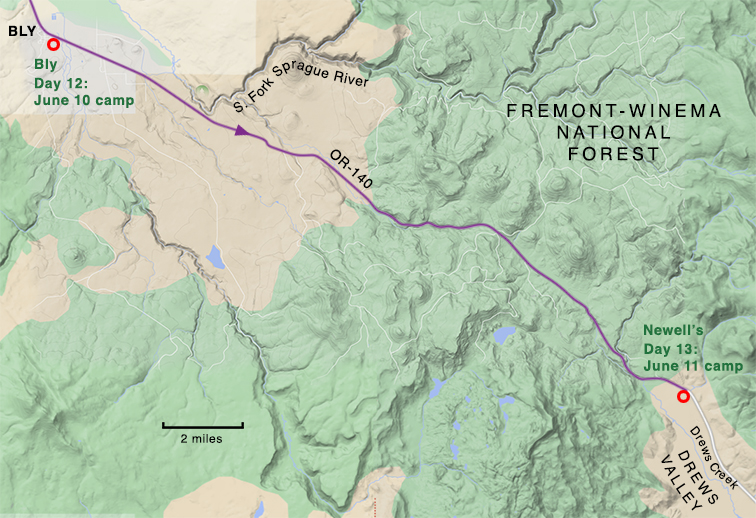

Dairy to meadow west of Bly

June 8. We get an early start and cross Yainax Butte, reaching our camping meadow at half past six.

June 9. Sunday. We spend the morning telling “plain truths”. In the afternoon we all walk to the tuff-beds, collecting bugs and flowers on the way. In the evening we have our first flurry of snow, and decide to abandon our cots.

Alexander described where they stopped to camp on June 8 in a letter to Beckwith:

We are just within the Klamath Indian Reservation about eight miles from Bly and are stopping on the edge of a pretty meadow surrounded by pines, over Sunday.23

The Expedition covered a lot of ground on the 8th thanks to its early start—about 27 miles. Wilson neglects to mention the town of Beatty but the Expedition had to pass through it. Based on a 1925 map of the Klamath Indian Reservation, the route from Yainax Ridge to Beatty was a much different and less direct path than that of today’s OR-140.24—there was nothing approximating today’s OR-140 at that time. The above map shows two possible routes the Expedition could have taken between Yainax Ridge and Beatty, but based on a couple of Alexander’s photographs, I believe that Alexander chose the northern route.

If Alexander’s “eight miles from Bly” estimate is accurate, then the “camping meadow” was on the banks of the Sprague River. The most likely place to examine tuff beds was a low cliff on the north side of the river about a half mile to the west of camp.

Although Alexander mentioned the Klamath Indian Reservation in her June 8 letter, Wilson says nothing about it in the scrapbook.

Meadow west of Bly to Bly

June 10. We camp at Bly, where we find the rustics ranged to receive us. “So this is Bly! Where is Nellie?”

At Bly the Expedition was forced to change its planned route:

We were hoping to go directly north from Bly to Summer Lake but they say there is too much snow in the mountains and we shall have to go round by Lake View—it will make a difference of over one hundred miles but perhaps we shall take in country that will be worth while seeing.25

Bly to Newell’s

June 11. Over the mountains from Bly to Newell’s. Mr. Greeley catches our first trout, and that night it snows.

I discovered that the Newell’s lived in Drews Valley, confirming that the Expedition traveled from Bly to Lakeview via the route of today’s OR-140.

Newell’s to Cottonwood

June 12. We search tuff beds on our way to Cottonwood. Here we are caught stealing fenceposts worth ten cents apiece. Finally we manage to secure enough wood for a fire. The coldest night yet.

Based on the photograph accompanying the June 12 entry in the scrapbook, the inspected tuff beds were a little over a mile north of today’s OR-140, along the foothills of the mountains west of Lakeview. I can find no evidence of a town of Cottonwood, however, there once was a Cottonwood post office along Cottonwood Creek, about 2.5 miles south of OR-140 and north of the intersection of today’s Sipp-Garrett Road and Westside Road.26 But the tuff beds certainly could not be said to be on Alexander’s way to this Cottonwood. I suspect that the Cottonwood Wilson mentions in her entry was some location along Cottonwood Creek, either at or north of where the creek crosses OR-140 today.

Cottonwood to Warner Canyon (via Lakeview)

June 13. An early start for Lakeview, where we sing the praises of porcelain bath tubs. We find Willis here with Don.

June 14. We leave Lakeview at 2:30 P.M., “Child of Satan” having been changed for a sorrel, and still another sorrel having been added to our train. We decide to call our camp “Camp Sorrel”. Item[?], six sorrel horses, four sorrel clothes bags, four sorrel beds, one sorrel cook, one sorrel dog for one night only. We look for fossils without success but learn that the rocks are very “assymmetrous” in Warner Cañon. Here we play our first game of whist.

The Expedition chose to stay at a Lakeview hotel rather than camp on June 13, then look for fossils in Warner Canyon the following day. I should note that the bedrock practically everywhere the Expedition traveled, from Montague and back again, is primarily volcanic in origin. There are very few pre-Quaternary sedimentary exposures.

Warner Canyon to the Bryan Ranch

June 15. Over the mountains again to Bryan’s Ranch, where we camp over Sunday. We fish for three hours and catch eight small trout, breaking the record up to this time. Mr. Bryan tells us the story of the Missourians expecting the back wheels of a wagon to overtake the front ones.

The ranch mentioned in the June 15 entry was undoubtedly that of Ahaz Washington Bryan (1858-1950). I learned early on that Bryan purchased a ranch in Clover Flat in 190227 but he was reported to be living at “Crooked Creek” (a creek roughly following US-395 from the Warner Mountains to the Chewaucan River) in 1900, according to the U.S. Census28. Precisely where the ranch was located in 1901 confounded me for a few years. It wasn’t until March 2024 that I finally learned where it was—about two miles south of the 1902 ranch—so it could hardly be described as being anywhere near Crooked Creek. I don’t understand why the 1900 U.S. Census said “Crooked Creek” when the ranch was so much closer to Clover Flat. I explore my problems with the Bryan Ranch location in some detail in the Appendix.

Bryan Ranch to Paisley

June 17. Another record broken! We leave camp at eight o’clock and reach Paisley at 4:30 that afternoon. We camp on the river bank, after having learned that there will be no potatoes in town until September.

This excerpt from a letter Alexander wrote to Beckwith helped identify where the party camped at Paisley:

O, I had such a beautiful swim in the Chewacan river, Martha, on our way here from Lake View. I started out with my camera to take a picture of the little town of Paisley and was disappointed in the view which seemed to promise better from a hill on the opposite side of the river so I decided to ford the river rather than go back a mile and cross the bridge. In two trips I had my clothes, camera and everything on the other side of the river. The stones were sharp and the mosquitoes settled on my shoulders and it was all I could do to resist battling with them. The trial of seeing my possessions safely landed over I put out for a deep pool sheltered by cottonwood trees and had the best time I have had on the trip so far—except for the fossil hunting.29

Based on Wilson’s note that “We camp on the river bank,” the photograph accompanying the June 18 entry, and the letter excerpt above, the party must have camped on the north bank of the Chewaucan River near where the road crossed over it. Alexander hiked west along the north bank of the river, thinking that she could get a good view of the town from the hills there. The base of those hills is about a mile from the current bridge across the Chewaucan. Finding no good views, she probably forded the river just east of where County Highway 2-08 and 331 Road intersect. It was then a good 0.75-mile hike to the point where she took the photograph with the June 18 entry; read more about this photograph and Paisley.

June 18. We spend the day at Paisley, waiting for Mr. Duncan, who arrives that evening. We visit the office of the Chewaucan Post, and see some fossils that we covet. Later we visit the drug store and take a lesson in trout fishing. “Every flick brings a trout.”

Although this caption sheds no light on the Expedition’s route, it’s an important one because Paisley is where George C. Duncan appears on the scene. Duncan, who had a ranch on the west shore of Silver Lake about 44 miles from Paisley (by modern routes), was the local fossil expert. He guided previous institutions to Fossil Lake to collect fossils and he would do the same for Alexander’s party.

Paisley to the Foster Ranch

June 19. We leave Paisley at ten o’clock, lunch at “Woodward’s Gardens”and reach Foster’s Ranch at seven. This was one of the prettiest roads we had seen around the south and west sides of Summer Lake.

What Wilson calls “Woodward’s Gardens” were the Woodward Hot Springs, now Summer Lake Hot Springs, about six miles up OR-31 from Paisley.

The Foster Ranch is another ten miles up OR-31 from the Hot Springs. The main ranch house that was there in 1901 still stands by the highway (the house is visible in one of Alexander’s photographs, partially hidden by trees).30

The Foster Ranch to the Duncan Ranch

June 20. Mr. Greeley who has been up the East side of the Lake rejoins us just as we are starting for Duncan’s ranch. We make twenty six miles to Silver Lake, in spite of an hour’s delay because of a breakdown. We see Indian pictures at the summit of the grade and leave some valuable additions to the collection.

The distance from the Foster to the Duncan Ranch by my estimation is about 28 miles but the 1901 route could have been more direct than today’s. The “Indian pictures” are the petroglyphs at Picture Rock Pass, about 19.4 miles up OR-31 from the Foster Ranch and just west of the highway. What the “valuable additions to the collection” were, who knows; hopefully, nobody vandalized the images. The Duncan Ranch was about nine miles beyond the Pass.

June 21. We spend the day at Duncan’s Ranch on Silver Lake. The wagon is repacked for the trip to Fossil Lake. We receive the Chewaucan Post’s account of our Expedition and learn much. In the evening we have a musicale at the Duncan house, the concert hall having done good service as a bathroom in the afternoon.

Below Picture Rock Pass, the road split and ran around both sides of Silver Lake. No doubt Duncan chose to take Alexander and the others around the south end of the lake, now a lightly used track called County Highway 4-15. Based on the photograph accompanying the July 11 and 12 entries, the party camped just south of the mouth of Duncan Creek.

Regarding the reference to the Chewaucan Post, Alexander et al. must have granted the newspaper an interview on June 18 when they visited the paper’s office in Paisley.

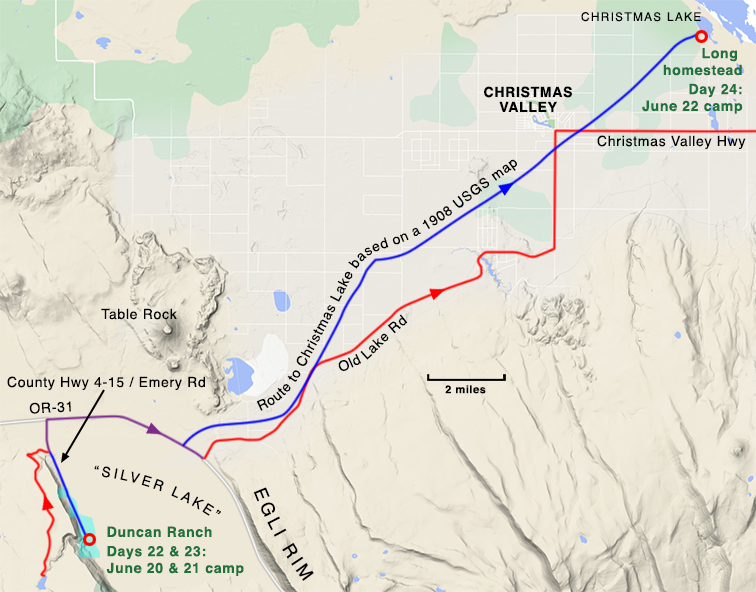

The Duncan Ranch to Christmas Lake

June 22. We start for the desert, make twenty-six miles to Christmas Lake and camp there for the night. Mr. Duncan gives us a fossil before we start, and we receive another on our arrival. The weather is exceedingly cold, and we decide that this lake is well named.

The party probably traveled around the north end of Silver Lake since it was a shorter route to the road up to Christmas Lake. Today, Old Lake Road runs from the NE side of Silver Lake up to the community of Christmas Valley, just west of Christmas Lake. Neither the road nor Christmas Valley existed in 1901. At that time there was a road that ran in a fairly direct line from Silver Lake to Christmas Lake (see the above map). I learned this from a 1908 USGS paper that included an accurate map of the region.31 Much of this old road can still be identified in Google Maps Satellite View; some traces of it can be seen crossing existing crop irrigation circles.

Based on Alexander’s photographs, the Expedition camped at or near the homestead of Alonzo Welch Long on the west shore of shallow, spring-fed Christmas Lake.

Christmas Lake to Fossil Lake

June 23. We reach Fossil Lake at noon and establish our first permanent camp. We make preparations for the hunt but do not start to work until the next day. We have traveled three hundred miles from Montague and have been on the way three weeks and three days. The feel that we have at last lived down the advice “Wait till you get to the desert.” Before leaving Christmas Lake Mr. Greeley shoots sixteen plovers, and we all feast merrily.

The 1908 USGS paper32 reported that Fossil Lake was only two or three feet deep,”a few acres in extent,” and “fed by a spring near its center.” It goes on to say that “it is claimed, riders have drunk [from the intermittent spring] when the lake was dry” so it was good enough for man and beast to drink from.33 The Expedition’s Fossil Lake camp was clearly located by the lake because Alexander specifically states in a letter to Beckwith “We camped near a spring.”34 Today, the spring apparently still feeds a lingering pond or two, visible in Google Maps Satellite View.

The Expedition spent five days collecting fossils while based at its Fossil Lake camp.

Fossil Lake to Mound Spring

June 29. Morning spent in packing fossils, which we bury, and in breaking camp. We go to Mound Spring to camp. In the evening all the men of the party call on the Pearl of the Desert.

To reach Mound Spring, located at the NE corner of the Fossil Lake basin, the party had to cross or go around a few miles of sand dunes. Mound Spring, described as being 75 yards across in 1908, was an important watering place for livestock in the early 1900s.35

Regarding the dunes:

Extending eastward from this lake [Fossil Lake], which is only a few acres in extent, is a region of sand hills, fully 6 miles long and averaging perhaps 2 miles in width. The prevailing west wind has heaped the sand into great dunes with steep eastern faces and gentle westward slope. These are slowly traveling eastward and have encroached nearly 3 miles on the part of the “high desert” known as Pine Ridge.36

The party spent three nights at Mound Spring.

Mound Spring to Christmas Lake

July 2. We retrace our steps for the first time on the trip, reach Fossil Lake, dig up our fossils and go on to Christmas Lake. Here we camp in a barn after the rain storm and groan over Christmas weather.

Since the Longs were the only people living near Christmas Lake at this time, there is no doubt that it was Alonzo Long’s barn where the party camped. Alonzo’s son, Reuben Long, wrote in his book, The Oregon Desert:

We had a notable big old barn of hand-hewn timbers, with pegs to hold it together, and the few nails used were the old square-cut kind.37

Christmas Lake to the U.R. Ranch

July 3. The men of the party leave for Logan Butte, while Uncle George escorts us to Silver Lake. We camp at the U.R. Ranch, where we hear that there is to be a dance in Silver Lake.

Logan Butte is about 43 miles (as the crow flies) north of Fossil Lake and was known as an important fossil locality as early as 1864. UCMP alum Samantha Hopkins, Professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Oregon, describes the Logan Butte rocks as middle Oligocene—”It’s not exactly the same stuff as the John Day Basin but the rocks are the same age.”38

Alexander had this comment regarding “the men of the party” and their mission to Logan Butte:

Mr. Furlong and Mr. Greeley left us on our way back here to go to Prices on a five day’s trip and learn if they could how the John Day region joins on to this.39

Mary Wilson doesn’t differentiate between Silver Lake, the lake, and Silver Lake, the community, so sometimes it’s difficult to determine which one she’s talking about in her entries. The July 3 entry seems to refer to both—the lake in the first sentence and the community in the second.

Two nights are spent at the U.R. Ranch.

The U.R. Ranch to the Duncan Ranch

July 5. To Mr. Duncan’s where we are to await the rest of the party. Francois, sleeping, writing, hot weather.

Alexander, Wilson, Ernest, and Willis hung out near the Duncan Ranch for three days until Furlong and Greeley returned from Logan Butte. “Francois” is probably a reference to reading material, perhaps Rabelais but possibly de La Rouchfoucauld (Francois is mentioned again in the July 22 entry).

The men returned from Logan Butte on July 7.

Duncan Ranch to the “Sandstone Ridge”

July 8. We all start for “Sandstone Ridge”, leaving Ernest and the wagon at Uncle George’s. We lunch at the U.R. Ranch and camp at the Ross Cabin where there is no water but where we find shelves for our canned goods!

July 9. Mr. Greeley and Willis go in search of information and provisions, while the rest of us walk up an old stream bed to the “Tanks.”

July 10. The horses are gone, and Willis is sent to U.R. to look for them. We find all but Chula and January and lead them by neckties to the Tanks. Annie meantime has found the jaw and the teeth of a reptile. Uncle George and Mr. Greeley camp at the Tanks, but the coyotes “have a chance.”

This trip to the “Sandstone Ridge” mystified me for the longest time despite a comment Alexander made to Beckwith in a July 7 letter:

When they come back [when Furlong and Greeley return from Logan Butte] we shall visit some chalk deposit where reptile remains have been found.40

Not having studied the geology of the area, I was skeptical of the existence of any sandstones or chalks in this area. So I searched for a geologic map and found a decent 1991 USGS geologic map of Oregon.41

To my surprise, it showed fossiliferous rocks that included sandstones and diatomite (a chalk-like sedimentary rock) some miles NE of the U.R. Ranch. These rocks are present in three main areas SE of Old Lake Road, the largest being the farthest east. I studied the areas on Google Maps Satellite View and the best exposures of these rocks are just south of the bend where Old Lake Road turns straight north toward Christmas Valley. They are within the Bureau of Land Management’s Black Hills Area of Critical Concern, along the west side. I believe this to be the “Sandstone Ridge.” Something Alexander wrote in a letter to Beckwith supports this theory:

Besides the Fossil L. fossils, we have some fish and reptilian remains from a strata 16 miles from there which may throw more light upon the geology of that country as it used to be.42

The exposures I’ve described are just about 16 miles from Fossil Lake (by roads existing at the time). Alexander had this to say about the “Sandstone Ridge” adventure in a July 26 letter to Beckwith:

Our trip to the sandstone strata, just after I wrote you from Silver Lake about our fossil finds, was a revelation. Nearly everything went wrong—we were camped too far from water, we spent two days trying to find the strata and we lost four of our horses. They were found three days later, two nearly dead from thirst, but it caused a lot of worry and inconveniences but I would not have given up that part of our trip for anything. Poor Mr. Furlong was upset from beginning to end. A trip could hardly have been more poorly planned but is has afforded us, Mr. F. excluded, more amusement than anything else we have done.43

The “Tanks” were probably livestock watering tanks. No reference to the “Ross Cabin” or anyone named Ross in the Silver Lake area could be found online and what the reference to the coyotes is about is anyone’s guess.

According to the June 8 scrapbook entry, Ernest and the wagon remained at the Duncan Ranch while the others set out for the “Sandstone Ridge.” The photograph appearing with this entry, taken near the north end of the Egli Rim and SE of the U.R. Ranch, would suggest that the party rode around the SE end of Silver Lake either on the way to the Ridge or on the return trip (or both).

“Sandstone Ridge” to the Duncan Ranch

July 11. Uncle George and the women of the party start back to Silver Lake, while the men stay out on the desert to hunt for the lost horses. We spend the night at U.R. Ranch and sleep in a bed for the third time in six weeks.

July 12. Breakfast at six o’clock, and after waiting two hours for Uncle George to be shaved, we go back to our camp at Silver Lake. We spend the day in getting clean and in enjoying the luxury of being clean.

The party, minus “the men,” returned to the Duncan Ranch by way of the U.R. Ranch. On the 13th, the women went “To Silver Lake to pack fossils.” My guess is that they were packing their fossils for shipment back to Berkeley but I have to wonder what arrangements they made—the nearest railroad was probably hundreds of miles away. In a November 10 letter to Beckwith, Alexander reported that:

Our fossils from Fossil L. arrived two weeks ago Thursday and Mary and I spent the afternoon unwrapping them and putting them on trays.44

So it sounds as if Alexander did have the fossils shipped back to the Bay Area, but, if she shipped them out of Silver Lake on July 13, it took more than 3.5 months for them to reach Berkeley.

The men, with the missing horses, returned late on July 13. The next day, the party prepared to leave for Crater Lake.

The Duncan Ranch to Antelope Flat

July 15. From Uncle George’s to Antelope Flat where we feast our eyes on trees and a roaring camp fire.

The Expedition set out from the Duncan Ranch, passed through the town of Silver Lake, and took a route approximating Bear Flat Road west towards Crater Lake. About 23 miles from the Ranch the party stopped to camp at Antelope Flat, a broad treeless area. Today, Bear Flat Road becomes Silver Lake Road just beyond this point.

Antelope Flat to Bear Creek

July 16. The beginning of horse flies, which occupy our attention for several days. We camp at Bear Creek and have our first mosquito smudge during dinner.

A 1925 map of the Klamath Indian Reservation45 shows that the route the Expedition took from Antelope Flat to Klamath Agency bore little resemblance to today’s Silver Lake Road. Assuming that the roads on the map remained relatively unchanged over the previous 24 years, the two roads overlapped for only about 2.6 miles! The 1925 road roughly paralleled Silver Lake Road but it was more direct in places and probably cut off a few miles.

The July 16 entry says that the party camped at “Bear Creek,” but the only Bear Creek near Silver Lake Road today is less than a mile and a half west of Antelope Flat, hardly a fit stopping point. So I suspect that Wilson’s Bear Creek is some other watercourse, perhaps the Williamson River (flowing west into Klamath Marsh), about 20 miles from Antelope Flat, or Skellock Creek, about 27 miles (these mileages are measured along today’s Silver Lake Road).

Bear Creek to “the ford”

July 17. A day of horse flies and misunderstandings. We finally reach the ford and camp on the farther side of the river, our tent being so far up on the hill that Ernest threatens to saddle a horse to call us to breakfast.

Alexander avoided Klamath Marsh by following what is now called Kirk Road south, then SW, out to today’s US-97, however, even that route was different in places than it is today.

The July 17 entry says “We finally reach the ford” and there is a ford across the Williamson River (here flowing south from Klamath Marsh) near the old Kirk railroad station where Kirk Road joins today’s US-97.46 And regarding the comment “We … camp on the farther side of the river, our tent being so far up the hill,” there is a low, forested hill across US-97 at this point.

“The ford” to Fort Klamath

July 18. On to the Klamath Agency where we are disappointed not to see the Applegate fossils. We lunch by a beautiful clear stream and go on to Fort Klamath and letters. Mr. Greeley receives only thirteen, so loses his bet. We camp by the river and play our last game of whist.

South of Kirk there was no road approximating today’s US-97. The 1901 route was a winding but fairly direct one from the vicinity of Kirk to Klamath Agency. To try and get to Klamath Agency by today’s forest roads would be a challenge, however, Google Maps does show interconnecting dirt tracks that, in theory, could get you there.

The party probably had lunch by Agency Creek on the 18th. Fort Klamath—the fort and not the town that bears the name today—was just 5.7 miles up the road from Klamath Agency but it was abandoned by the military in 1890. Although I could not confirm that the town of Fort Klamath, about a mile NW of the fort, existed in 1901, I am assuming that it did and that the post office, established in 1879, was located there. If so, then the party camped along the Wood River.

Fort Klamath to the “first dry camp”

July 19. Mr. Greeley starts home, and we try to start for Crater Lake. After waiting three hours and a half for the blacksmith to shoe the team, we start on our way. We reach our first dry camp at seven and decide on tomatoes, oysters and pears for supper.

This entry mentions that Greeley left to return to the Bay Area. Alexander explained in a July 26 letter to Beckwith:

Mr. Greeley left us at Ft. Klamath to fill a school position—his first start in life and of course for that reason doubly important but we cannot forgive for not being willing to lose a day or two in order to see Crater Lake.47

It’s possible that one of those 13 letters Greeley collected at Fort Klamath (see the July 18 entry) contained the news about his “school position.”

We know that Alexander’s party could travel at least 23 to 30 miles a day but we can only guess at its rate of speed. The hours of daylight were long so traveling eight to twelve hours a day would not be difficult, given decent road conditions, an easy grade, and good weather. It is only 16.5 miles (via today’s OR-62) from Fort Klamath to Annie Spring with a fairly easy and consistent 3% grade so the Greeley goodbyes and horse-shoeing must have taken up most of the day. The party reached its camping spot, its “first dry camp,” at 7:00 PM but where that was is anybody’s guess. For my map, I randomly chose a point about 11 miles from Fort Klamath, near today’s Annie Falls turnout.

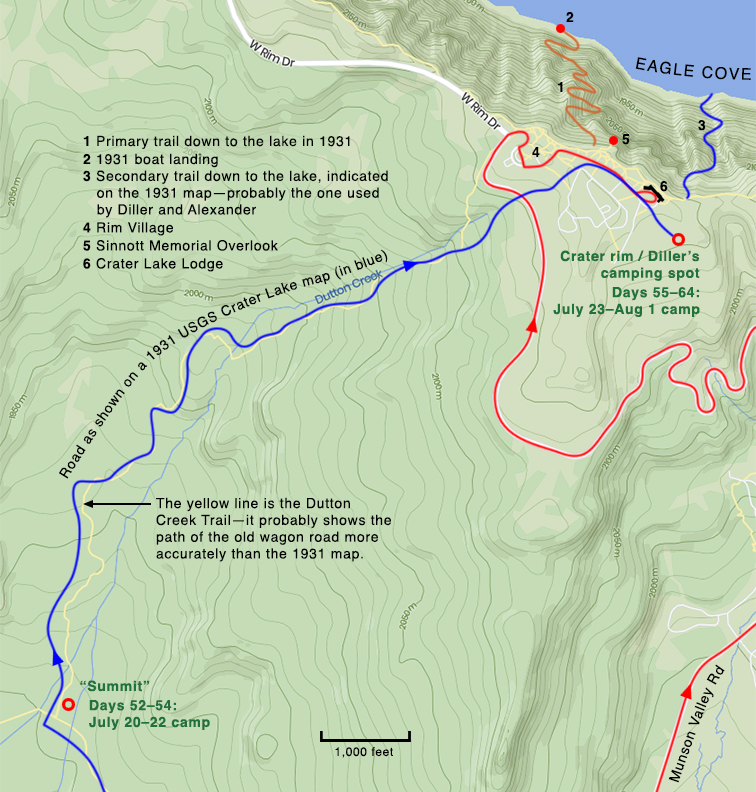

“First dry camp” to beyond the “summit”

July 20. After eating many sweet crackers, we start up the grade. At 11:30 we stop for breakfast-lunch and remain at the spring until four o’clock. The green apple man takes part of our load to the summit, which we finally reach, disgusted with the people who have praised this road. We camp a mile and a half below the lake under beautiful fir trees.

“The spring” is Annie Spring, the source of the waters of Annie Creek. Today, the spring is about 60 yards beyond Crater Lake National Park’s Munson Valley Road entrance kiosk.

In 1901 there was no road to the rim via Munson Creek. The road to the crater rim headed NNW from the spring up to a saddle west of Munson Point and then roughly paralleled Dutton Creek up to the area of today’s Rim Village.48 The “summit” referred to in the scrapbook entry is not the crater rim but the saddle above Annie Spring. The grade up to it is quite steep, being almost 7%, so it’s no wonder that the party enlisted the help of the “green apple man” to make the ascent easier. Wilson wrote “We camp a mile and a half below the lake”—if this was as the crow flies, then my map shows the general area where the camp was situated.

July 21. We go on horseback to Crater Lake and spend the day with Professor Diller. After lunch we go down to the lake and take a row. Before we leave we decide to spend many days camping on the rim.

The party spent the 21st with Joseph Diller of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) at his camp near the crater rim. In the afternoon, Alexander, Wilson, and Furlong (at least) climbed down the rim49 and rowed out on the lake in Diller’s boat.

July 22. We spent the morning taking photographs and collecting flowers below our camp, the afternoon in finishing Francois.

The Expedition members remained near the “summit” camp by Dutton Creek on this day.

The “summit” to the crater rim

July 23. We prepare to move our camp to the rim of the Crater. While waiting for the teamster we go on a flower hunt, which is not a success. We dine with Professor Diller, who presents us with a half of venison, and camp for the night across the snow bank.

The elevation change from the party’s camp to the rim was greater than 950 feet, giving the road an average grade of almost 7%. It’s not surprising that Alexander’s crew needed a teamster’s assistance but what is surprising is that there was one in the neighborhood; perhaps Diller had retained him. Upon reaching the rim, the Expedition set up its camp across a snow bank from Diller’s.

July 24. We move into Professor Diller’s camp. Annie starts out to take snow pictures and loses her large camera over the precipice. In the afternoon we row along the shore and look for the camera.

Alexander told Beckwith in her May 2 letter that she brought two cameras on the Expedition. In her July 26 letter she explains how she lost “her large camera:”

My nerves were not very steady from a foolish walk I had taken the day before down one of the ridges, got into a place where everything was ready to slip from under me and had the shock of seeing my nice big camera that I had set on a rock for an instant, slide away from me and could hear it strike three or four times as it bounded to destruction.50

Hike from rim camp to Llao Rock

July 25. Fourteen hours of walking and hard climbing to Llao Rock. This is the day of the famous snow slide!

Professor Diller may have suggested the Llao Rock hike to Alexander. He recommended it in his 1902 paper:

The most instructive day’s walk from the rim camp …, but a rather hard one, is along the western crest to Llao Rock.51

Alexander described the adventure and the “famous snow slide”:

This is a wonderful region! I did not begin to take it in when we were here before. The lake with its intensely blue water and the tremendous cliffs overshadowing it. Mr. Furlong and I walked over to Llao Peak just north of us day before yesterday, a distance of twelve miles going and coming but it took us fourteen hours to make it. We had two peaks to cross, kept to the right going around the first one [The Watchman, elevation 8,013 feet; the trail goes around the left side today]—the footing was good—heavy turf—but steep and perilously near the edge of the crater. …

Crossing the second peak [Hillman Peak, elevation 8,151] we kept to the left and came against a huge snow bank—it followed the steep incline of the mountain for three hundred feet below us and ended in a nest of big boulders. My heart sank at the thought of crossing it. Two thirds of the way down it became icy and I felt I could not go another step and I begged Mr. Furlong to go ahead and as soon as he reached the bottom safely to let me slide and catch me. O, it was the most ungraceful thing I ever did. I don’t know just how I came down. Mr. Furlong says he caught me by the foot, but I bore him along with me for several yards. Coming back in the afternoon it seemed even worse such a laborious ascent. I dared not look below and had it not been for my tripod to steady me I doubt if I ever could have done it but now that the trip is accomplished I feel like starting right out and doing it over again. It was the most wonderful walk I ever took—such height, depth and breadth of scenery never can be described.52

Alexander says that the round trip hike to Llao Rock and back was 12 miles and that appears to be fairly accurate.

Attempted ride to Sun Creek from rim camp

July 26. First Expedition to Sun Creek. We see two deer but the gun is “on the other saddle.” We go home in detachments and have many wanderings.

We know from one of Alexander’s letters that this first trip to Sun Creek was unsuccessful. In describing some of her photographs to Beckwith, she wrote:

The view of Sun Creek Cañon was taken on a day when we attempted to make the trip on horse back and failed.53

Sun Creek originates somewhere north of Vidae Falls and flows SE, eventually joining Annie Creek about two miles north of Fort Klamath. This trip to Sun Creek was on horseback but a second was on foot (see the August 1 scrapbook entry, below).

July 27. We spend the morning writing letters and in the afternoon walk along the rim to get a picture of the sphinx.

I could find no reference to any rock formation at Crater Lake called the sphinx but I discovered that the photograph associated with this caption was taken just south of Discovery Point (see Photo #89 in Part 2).

From rim camp to Wizard Island

July 28. We have a visit from Philip Bowles and Rudolph Schilling, who do justice to our camp fare. Annie and Willis row over to the Island in the afternoon. In the evening “Doctor Burnett of Ashland” calls and brings us a roll of films from Mr. Schilling.

This was the first of three trips that Alexander made to Wizard Island. She took three photographs there, probably on her July 31st visit.

From rim camp to the Palisades

July 29. Doctor Burnett’s party spends the day at the Lake. In the afternoon Annie and Willis go to the Palisades, returning by moonlight.

The Palisades are on the opposite side of the Lake from Discovery Point. Wilson’s scrapbook entry doesn’t say how Alexander and Willis got there but one of Alexander’s letters to Beckwith did:

We rowed across the lake six miles one afternoon to the Palisades, to try some fishing and came back by moonlight. The others built a big fire on the edge of the crater which helped us to locate our landing place but we did not reach the top until after ten o’clock.54

From rim camp to the Phantom Ship

July 30. To “Phantom Ship” in the morning and to the Island in the afternoon. We are caught in the rain on the trail, and break another record, two hours to climb to the rim.

Since Diller told Alexander that he planned to return on August 1 to “put [the boat] under cover for the winter,” the party had only two more days to use the boat so they made good use of it on the 30th and 31st. It sounds as if the arrival of the rain prompted the party to speed up their ascent to the rim so if two hours was a record, it says much about the difficulty of the trail (of course it could be a record for how much slower the climb was).

From rim camp to Wizard Island

July 31. Annie and Willis go to the Island for the fish-pole and climb to the Crater. It rains most of the night.

Alexander described this visit in a letter to Beckwith:

Another day we rowed over to Wizard Island and climbed the cone. You should have seen the red paint brush growing among the red fire-burnt rocks on the rim! We stayed over an hour on the top and tried to take it all in—this queer little island made up principally of rocks and black sand rising so abruptly and yet so symmetrically to 900 ft. above the deep blue water. The firs you remember grow quite thick all round the base but they are covered with yellow moss and have a sort of melancholy, {?} look about them. The only birds we saw on the island were ravens. They hopped awkwardly over the lava and seemed to have no spring in them. Afterwards in rowing around the island we started up a number of ducks with their young families.55

Hike from rim camp to Sun Creek

Aug. 1. Mr. Hershberger arrives in the morning and goes in search of the lost camera. He finds it and brings back the pieces. Annie and Willis go to Sun Creek and return with five fine trout.

Alexander described this trip to Sun Creek in a letter to Beckwith:

Our last Expedition was to Sun Creek to do some fishing. It rained during the night so Willis and I did not get started until after nine. Sun Creek begins about three miles around to the East of where our camp was, Martha. There is a big mountain to climb, then a comparatively level stretch for a mile or more, then a very steep descent to reach the creek. The fishing begins below the falls three miles down. The cañon is thickly wooded. I should have liked nothing better than to have camped there several days but as it was that day we had no time to lose. We did take time enough when we reached the stream to make some strong tea for our lunch and then had only one hour and a half for fishing. I did catch four full sized Dolly Varden but that was all, and then I lost Willis and had to go back the long way alone. I should have tried to cut off some of the climbing had I not left my camera on the ridge but aside from feeling worried about the small boy I was almost glad he was not along for my skirt had gotten so wet and dragged out and loaded with dirt that it seemed as if I could not wear it any longer so I took it off, threw it over my shoulders and with my fish and rod started back. Don’t think I did not wait and call for Willis. I wasted an hour doing this and then reached camp only a quarter of an hour after he did with his one fish. It was nine o’clock but Mary and Mr. Furlong had waited supper for us and we had the fish then and there. I must confess that day’s work was the hardest I ever did in my life.56

From this description, Alexander and Willis hiked, and did not ride, to Sun Creek. The “big mountain to climb” is Garfield Peak, the “comparatively level stretch” is the flat between Garfield and Applegate Peaks, and the “very steep descent” is down the eastern face of Vidae Ridge. Having climbed Garfield Peak and crossed the flat myself, I can say that Annie and Willis were in excellent physical condition. At least Alexander admitted that the “day’s work was the hardest I ever did in my life.”

Crater rim to Fort Klamath

August 2. We leave Crater Lake with great reluctance. We reach Fort Klamath at three o’clock, all but Annie, who comes in at half past five, __ at having shared in our longings to return to the Lake.

Alexander explains to Beckwith why she was late in arriving at Fort Klamath:

It wasn’t a very happy day—I stayed behind the rest so as to take pictures of the cañon and Pat, my horse, got away from me. I couldn’t blame him for wanting to go back to Crater lake but he shouldn’t have left me so in the lurch when I was so tired, footsore, hot and the road dusty. I walked back four miles and then a camper lent me his horse.57

Fort Klamath to Cherry Creek

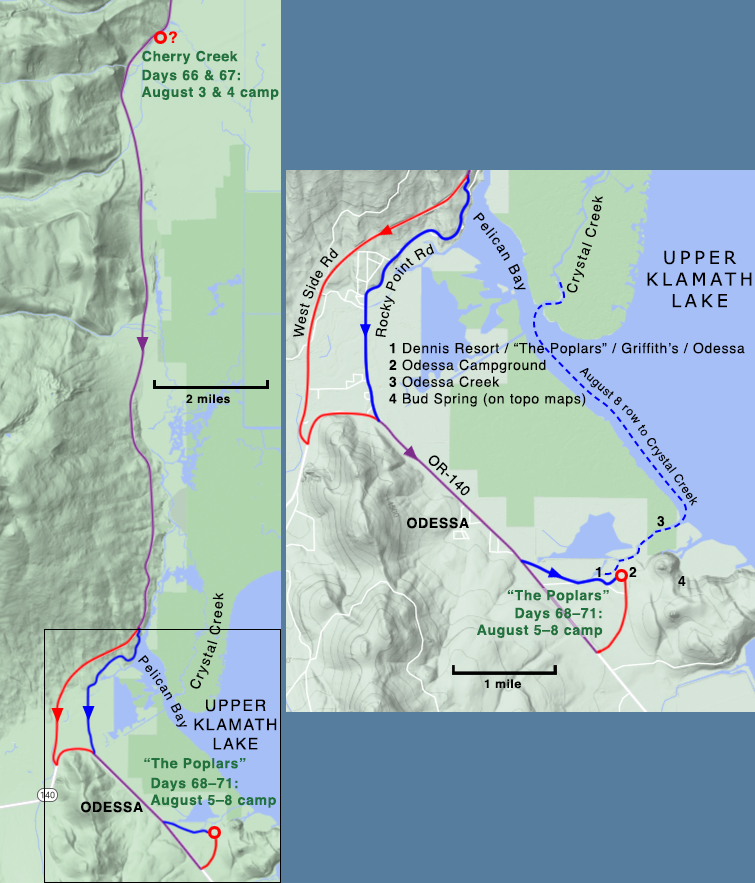

August 3. We start for Pelican Bay and travel half a day to Cherry Creek. Ernest catches five Dolly Varden trout, and the game warden sups with us. We find the mosquitoes so active that none of us get much sleep.

It is no surprise that the party chose to go around the west side of Upper Klamath Lake. As noted earlier under the Expedition planning & departure section, Alexander told Beckwith “… we shall come down the west side of Klamath lake and do some lake fishing.”

At Fort Klamath, Alexander and crew headed south, probably following today’s Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway/West Side Road. If that was the route, they would hit the lower reaches of Cherry Creek about nine miles out from Fort Klamath. Although the Creek roughly parallels the east side of the road for about 2.25 miles more, the better fishing was probably at the northern end where it was wider, so the party probably camped near there.

August 4. Sunday. We spend the day in making up lost sleep. Mr. Furlong goes hunting with Mr. Hershberger but they return empty handed. They could not find the deer that they shot. Mr. Cunningham presents us with a quarter of venison.

It’s not clear whether this is a reference to Mr. Herchberger, the man who recovered Alexander’s camera lens at Crater Lake, or George Hershberger of Odessa. No information could be found on Mr. Cunningham.

Cherry Creek to “The Poplars”

Aug. 5. Up at half past four, and on our way soon after six. We camp at “The Poplars” but decide to move to higher ground in the morning! We fish in the afternoon, with no success.

“The Poplars” was the popular name for what had been, up until that time, the Dennis Resort. It was known as “The Poplars” because of the trees that grew there.58 Just prior to the Expedition’s arrival, Dennis sold the resort to B.B. Griffith who renamed the place Odessa, today the name of a nearby town.

The Expedition camped four nights there, fishing and trying to dodge the mosquitoes.

Row from “The Poplars” to Crystal Creek

August 8. Fishing on Crystal Creek. The minister from San Jose joins our party, but the less said of the Expedition the better! Annie catches many trout!

It’s about a three-mile row from “The Poplars” location to the mouth of Crystal Creek at the narrows of Pelican Bay.

“The Poplars” to Klamath Falls

August 9. We go by boat to Klamath Falls, Ernest and Willis taking the wagon and horses around the lake. We stay at “Hotel Linkville” and in the evening go to a “show” and a dance.

While Alexander, Wilson, and Furlong took a leisurely cruise to Klamath Falls and the Linkville Hotel,59 Ernest and Willis took the wagon and horses around the lake, roughly following today’s OR-140 and Lakeshore Drive.

August 10. We go to see the snakes in the morning and the tight-rope walks in the afternoon.

Regarding the snakes, around the turn of the century:

There were rattlesnakes by the thousand on Buck Island [a short boat trip from Klamath Falls], so they put hogs on it to kill them off.60

Klamath Falls to the Way Ranch

August 11. We start on our way again at seven thirty in the morning, and camp at Hay Cabin. Ernest finds a hat which is hereafter a feature of the landscape.

Alexander and crew left Klamath Falls and headed SW to Keno, following what is today’s OR-66. OR-66 connects Klamath Falls to Ashland and some portion of the road was originally part of the Applegate Trail. At the time of the Expedition, it was called the Southern Oregon Wagon Road.61

About six miles beyond Keno, the Expedition turned onto Topsy Grade Road and followed it and the Klamath River about 13.6 miles all the way to the California border. The road’s name has not changed in the subsequent 120+ years.

There was no one by the name of Hay living along the upper Klamath in 1901 and I’m convinced that Wilson meant Way, not Hay. Thomas C. and Mary E. Way had a farm on Topsy Grade Road just north of the Oregon-California border. The party covered almost 30 miles on August 11.

Way Ranch to McClintock’s Ranch

August 12. We go through Klamath River Cañon and lunch at Klamath Hot Springs. Here we sleep in hammocks until we are banished by stern glances. We camp that night on a side hill at McKlinnick’s ranch.

Topsy Grade Road begins dropping down into the Klamath River canyon just beyond the old Topsy stage station—this part is technically the Topsy Grade. When the road reaches the Oregon-California border (the road actually crosses the border five times) it becomes the Ager-Beswick Road. Five miles beyond the Way Ranch and about three miles south of the last “border crossing,” the party reached Klamath Hot Springs and stopped there for lunch.

From the Hot Springs the party traveled another ten miles to reach “McKlinnick’s ranch.” This was another name that Wilson got wrong. The correct name is McClintock.

McClintock’s Ranch to Montague

August 13. Our last day out. We are up before daybreak and ready to start by sunrise. We pass through Ager and after a hot, dusty ride, finally reach Montague. Our only stop on the way is at the Alkali Spring.

The “Alkali Spring,” looking much the same as it did over 120 years ago, is about 1.5 miles past the McClintock place. The spring is just a few yards from the road, on the east side.

From the spring it was only about 19 miles back to Montague, but Alexander and the others had to pass through Ager first.

The Expedition set out on May 30 and returned on August 13, a total of 76 days. Not counting the numerous side trips and outings, Alexander’s “loop”—from Montague and back—covered more than 600 miles.

Final thoughts

After studying Alexander’s route, one thing I found interesting was the change in the approach to road construction over time. Although many of the early roads probably followed existing Native American trails, few settlers seemed willing to modify them to accommodate wheeled vehicles. Roads often had steep grades with no switchbacks. If the road was steep, people enlisted the aid of a teamster or added a couple more horses to haul the wagon. Today, switchbacks are common—just look at Munson Valley Road in Crater Lake National Park and how it climbs up to Rim Village.

I finally read Barbara Stein’s 2001 biography of Annie Montague Alexander62 months after completing my study of the Fossil Lake Expedition. Alexander truly was ahead of her time. Few women in the early 1900s had the independence, the education, and the business savvy that Annie possessed. The UC Museum of Paleontology owes a debt of gratitude to Martha Beckwith, Alexander’s friend who convinced her to audit one of John C. Merriam’s paleontology courses in 1900. Without that push from Beckwith, there probably would not be a Museum of Paleontology—or a Museum of Vertebrate Zoology for that matter—at UC Berkeley.

- The Joseph and Hilda Wood Grinnell Papers, BANC MSS 73/25 c, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; Box 5, Letters from Annie Montague Alexander to Martha Beckwith 1899-1940 undated.

- We know that Beckwith received a set because Alexander said as much in a post-Expedition letter (a “1901” letter in the Grinnell Papers—see Footnote 1): “You will see from the photos I send you that there was not nearly as much snow at Crater Lake as when we were there two years ago.” She then goes on to comment on some of the individual photographs.

Merriam acknowledged receiving a set in a December 20, 1901, letter to Alexander: “I am greatly obliged to you for the set of photographs which I found on my table some time ago. Some of them ought to be published in connection with a scientific paper on the Fossil Lake region.” (from UCMP’s Annie M. Alexander Papers, Box 2, Series 1, Correspondence 1901–1949, K–W).

- I know that they both took the course because in a letter written to Beckwith two weeks after returning from the Expedition (probably August 28 or 29), Alexander mentioned a General Paleontology course that she was taking from Merriam, saying “It really preceeds [sic] the course we took [my italics].” The letter is housed in the Grinnell Papers (see Footnote 1).

- Grinnell Papers. From a February 7, 1901, letter.

- Ibid.

- Grinnell Papers. “Spring” 1901 letter to Beckwith, probably written around April 10. The “Mazambas” Club should be Mazamas Club; it was a Portland-based mountaineering organization founded in 1894.

- Grinnell Papers. May 2, 1901, letter. It’s worth pointing out that the fossils just “bought by the university” were collected “in the region of the Crooked River and Logan Butte, south of the John Day Basin,” by L.S. Davis and V.C. Osmont making “the material now available … representative of all the phases of the faunas of the John Day region.” These quotes are from Merriam, J.C. 1906. Carnivora from the Tertiary Formations of the John Day Region. Bulletin of the Department of Geology, University of California Publications 55(1):1-64. Read the paper on Google Books (retrieved January 21, 2025). Osmont later participated in the 1902 Shasta County Expedition (retrieved January 21, 2025).

- Grinnell Papers. May 2, 1901, letter. In the first paragraph, Alexander refers to a trip she and Beckwith took through northern California and southern Oregon, including Crater Lake, in 1899.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Read more about the Solano on Wikipedia (Retrieved January 21, 2025).

- A rail line had reached Montague in 1887. A connection from Montague to Yreka opened two years later. From Historic Sites and Points of Interest in Siskiyou County (Retrieved January 21, 2025).

- Denny’s Map of Siskiyou County, compiled by Edward Denny & Co., map publishers, San Francisco, CA. 1905. The discovery of this map was crucial in determining the Expedition’s route between Montague and Merrill.

- Grinnell Papers. June 10, 1901, letter.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. Klamath Echoes: Merrill-Keno, No. 7. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. Pp. 82 and 84. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Denny’s Map of Siskiyou County, compiled by Edward Denny & Co., map publishers, San Francisco, CA. 1905.

- Grinnell Papers. June 10, 1901, letter.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1969. Pp. 6-7.

- Grinnell Papers. June 10, 1901, letter.

- The Henley location for the ranch is from Klamath County Historical Society. 1977. Klamath Echoes: Merrill-Keno, No. 15. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. P. 46. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Grinnell Papers. June 10, 1901, letter.

- Pre-OR-140 roads from a 1925 Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs map of the Klamath Indian Reservation. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Grinnell Papers. June 10, 1901, letter.

- From geoview.info. Retrieved January 21, 20125.

- Rose, A.P., R.F. Steele, and A.E. Adams. 1905. An Illustrated History of Central Oregon: Embracing Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Crook, Lake, and Klamath Counties, State of Oregon. Western Historical Publishing Company. P. 880. Read it on Google Books. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Bryan’s 1900 location from U.S. Census information found on ancestry.com. Retrieved December 18, 2022. A deed posted on ancestry.com shows that land in Lake County, presumably the Clover Flat parcel, was turned over to Ahaz Bryan by Lewis and Mary Green on May 5, 1902, so there’s no disputing that the purchase was in 1902.

- Grinnell Papers. July 7, 1901, letter.

- Personal communication, a June 12, 2022, email from Silver Lake resident and local historian, Elaine Condon. Elaine’s great great grandfather built the house, completing it in 1889. Connie Soja put me in touch with Elaine.

- Waring, G.A. 1908. Geology and Water Resources of a Portion of South-Central Oregon. Water Supply Paper 220. U.S. Geological Survey, Government Printing Office, Washington. Read the publication; the map is on page 60. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Pp. 12 and 66.

- Grinnell Papers. July 7, 1901, letter.

- Waring. P. 66. Mound Spring no longer appears to be active. Still, you can see where it once was because the plant life is a different color green in Google Maps Satellite View (last checked June 14, 2023). Plug these coordinates into Google Maps: 43.349527, -120.401997.

- Ibid. P. 11.

- Jackman, E.R., and R. Long. 1964. The Oregon Desert. Caxton Press. P. 32. Much of the book can be read online. Both retrieved January 21, 2025.

- See the Summer 2015 issue of My Public Lands, pp. 14-15. Retrieved January 21, 2025.

- Grinnell Papers. July 7, 1901, letter.

- Ibid.

- Walker, G.W., and N.S. MacLeod. 1991. Geologic Map of Oregon. U.S. Geological Survey. Scale 1:500,000. Retrieved January 21, 2025. The map described the rocks:

Tuffaceous sedimentary rocks and tuff (Pliocene and Miocene)—Semiconsolidated to well-consolidated mostly lacustrine tuffaceous sandstone, siltstone, mudstone, concretionary clay stone, pumicite, diatomite, air-fall and water-deposited vitric ash, palagonitic tuff and tuff breccia, and fluvial sandstone and conglomerate. … Vertebrate and plant fossils indicate rocks of unit are mostly of Clarendonian and Hemphillian (late Miocene and Pliocene) age.

- Grinnell Papers. November 10, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. July 26, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. November 10, 1901, letter.

- 1925 Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs map of the Klamath Indian Reservation. Retrieved January 28, 2025.

- McArthur, L.L. 1974. Oregon Place Names. Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR. 835 pp. “Kirk” entry.

- Grinnell Papers. July 26, 1901, letter.

- From a map in Diller, J.S., and H.B. Patton. 1902. The Geology and Petrography of Crater Lake National Park. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. 167 pp. The map is Plate I., page 17. Retrieved January 28, 2025.

- One might wonder what route Diller and Alexander took from the rim down to the lake. I found a 1931 USGS topographic map of Crater Lake National Park (retrieved January 28, 2025) that shows two routes down. The principal trail began west of today’s Sinnott Memorial Overlook (built atop Victor Rock) and had several switchbacks down to the water, ending just west of Eagle Cove; a label at the end of the trail read “Boat landing.” The secondary trail was a much more direct route that began east of today’s Lodge and ended in the middle of Eagle Cove. The map indicated that a benchmark, “BM 6179,” presumably placed by the U.S. Coast & Geodetic Survey, lay at the bottom of the trail.

Diller’s comment in his 1902 paper—”By far the most impressive and, to the geologist, most important trip about Crater Lake is by boat from Eagle Cove”—convinced me that the secondary route was the one used by Alexander and the others. Also, the map in Diller’s paper places his camp SW of today’s Lodge and close to this route’s trailhead down to the lake (see footnote 46). But even knowing where to look, I still can’t see any trace of the trail on Google Maps Satellite View, in 2D or 3D.

A park employee told me that the trail was right below the Crater Lake Lodge and that parts of the trail were still visible. I studied the area carefully on Google Maps Satellite View in both 2D and 3D but could see nothing that I could confirm as a trail.

- Grinnell Papers. July 26, 1901, letter.

- Diller & Patton, 1902. The quote is from page 8.

- Grinnell Papers. July 26, 1901, letter.

- Grinnell Papers. A post-expedition “1901” letter written from Oakland, CA.

- Grinnell Papers. “Fall 1901” letter, probably written August 28 or 29.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1965. Klamath Echoes: Boating. Vol. 1, No. 2. Klamath County Historical Society, Klamath Falls, OR. P. 31. Retrieved January 28, 2025.

- The Linkville Hotel was located on what is today’s Main Street opposite Conger Avenue. It was razed in 1923. From Klamath Falls News, an online news source. Retrieved August 16, 2022 (NOTE: This site could not be reached on March 4, 2025).

- Klamath County Historical Society. 1965. P. 82.