UCMP and the development of the ichthyosaur quarry at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park

by David K. Smith (based on a 2015 UCMP wall calendar of the same name)

Introduction

While doing field work for his Ph.D. dissertation in 1928,1 Siemon Muller, who later became Professor of Geology at Stanford University, discovered the bones of large ichthyosaurs in West Union Canyon in the Shoshone Mountains of Nevada, just east of the ghost town of Berlin. Berlin was established as a mining town in 1897 but, after 13 years of diminishing gold and silver production, most of its residents drifted off to greener pastures. However, many of the town’s buildings were maintained over the years.

Muller, who was more interested in invertebrates, notified UCMP of the ichthyosaur find in 1929. Fearing that excavation would be difficult because the bones were reported to be in hard limestone, no one from UCMP followed up on the discovery.

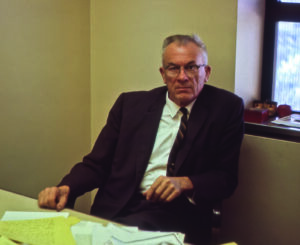

Twenty-three years later, in 1952, Margaret Wheat2 of Fallon, Nevada, brought the Berlin ichthyosaur fossils to the attention of Charles Lewis Camp. Camp had been teaching at Berkeley since 1922, one year after the establishment of UCMP. He was an authority on fossil reptiles and amphibians, had collected extensively in the American Southwest, had led successful fossil collecting expeditions to South Africa, was a respected writer on American pioneer history (his “other career”), served as Chair of the Department of Paleontology for 19 years (1930-1949), and was Director of the museum for six (1940-1946).

A quick 1953 visit to West Union Canyon site was enough to convince Camp that it was an important one. He returned in 1954 to begin excavations. After just three days of exposing ichthyosaur bones, he made this entry in his field notes:

I am beginning to think that it would be well to leave this specimen in place for public exhibition in this spot and will mention to Mrs. Wheat tomorrow the possibility of making a park of this place.3

Seven days later, on July 2, Camp realized that he was seeing something quite extraordinary. He wrote:

This is a thing that should be preserved in situ for all to see. It will probably not be duplicated again in this world.4

Camp and Mrs. Wheat made a formidable team in lobbying for the creation of a park at the ichthyosaur locality. They brought representatives from the Forest Service, Nevada Parks Commission, and state legislature out to the site and all were impressed by the concentration of fossil bone. The efforts of Camp and Wheat paid off, for the following year, the legislature moved to protect the area by designating it Ichthyosaur Paleontological State Monument. In 1957 it achieved State Park status, and then in 1970 (after the state purchased the neighboring ghost town of Berlin), became Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park.

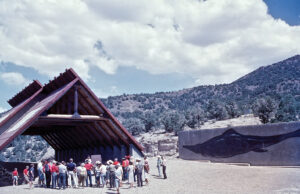

The bonebed that visitors see today, protected by the park’s A-frame shelter, encompasses most of the skeletons of four ichthyosaurs and portions of two others. But one must keep in mind that Camp discovered the bones of some 37 individuals in ten quarries along a mile-long stretch on both sides of the canyon, and if more quarries were opened up, undoubtedly more specimens would be found. It was not too surprising then, when in 1973 the Secretary of the Interior designated the ichthyosaur site a National Natural Landmark, selected on account of its “… outstanding condition, illustrative value, rarity, diversity, and value to science and education.”5

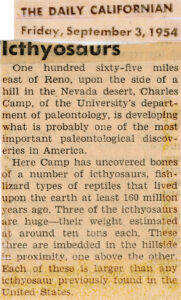

On the ichthyosaurs

The ichthyosaurs of West Union Canyon were named Shonisaurus popularis by Camp. They are found in marine sediments (a shaly limestone) that were deposited some 215 million years ago during the Triassic period, a time when a sea covered much of what is now western and central Nevada and dinosaurs were just beginning to dominate the land. Camp was surprised by the number of individuals represented at the site and theorized that the animals may have beached themselves and died. Current thinking is that the ichthyosaurs died in deep water.

Credits abbreviations

This article contains many images. The bold red letters associated with each image or at the end of an image’s caption refer to these sources:

A Charles L. Camp papers, Series 5: Film and photograph collection, Carton 1: “Miscellaneous films and negatives, unorganized.” UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

B Sam Welles collection of 35 mm slides, Binder X, sheet entitled “NEVADA ICHTHYOSAUR, pg. 1.” UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

C “1948-1966” scrapbook of newspaper clippings. UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

D Huff Family Archives.

E Courtesy of the Nevada Department of Transportation.

F Joseph T. Gregory collection of 35 mm slides. UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

G © 2024 David K. Smith.

H Charles L. Camp papers, Series 4: Miscellany, Box 5 : “Miscellaneous illustrations, photographs, maps, documents.” UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

I Sam Welles Papers, box entitled “Welles Misc. (incl. photos).” UCMP Archives. © 2023 University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP).

Camp’s first site visit, 1953

One source6 suggests that Margaret Wheat was with Siemon Muller at the time of the West Union Canyon ichthyosaur discovery and, when revisiting the locality in 1952, she found that she could expose a number of bones simply by sweeping them off with a broom. She collected some vertebrae, at least one being a foot in diameter, and later contacted Professor of Paleontology and Director of UCMP Charles L. Camp in Berkeley. Margaret told him about the locality and described the vertebrae that she had picked up.

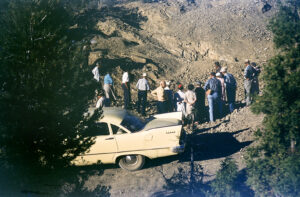

Camp was intrigued and agreed to pay Wheat a visit. In October of 1953 he headed to Fallon with one of his graduate student classes, Professor of Paleontology J. Wyatt Durham, Lecturer in Paleontology and Principal Museum Scientist Sam Welles, Siemon Muller from Stanford, and Norm Silberling, one of Muller’s grad students. Suitably impressed by the vertebrae, the whole crew drove out to West Union Canyon to look over the area. The group quickly found a number of other bones in multiple locations near the mouth of the canyon.

By the end of the day, Camp was convinced that the site should be excavated. In his field notes he wrote “Had long discussion this evening at Mr. Wheat’s home re possibilities of getting permits and possible plan of work next summer.”7

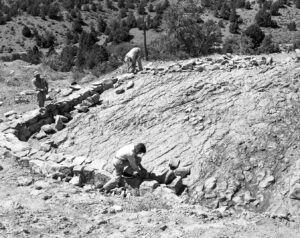

Excavation begins, June 1954

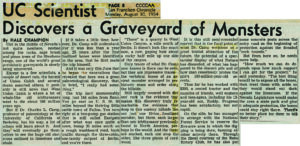

Publicity and media attention

Camp knew that public opinion could be helpful in convincing Nevada decision makers that the ichthyosaur site was a unique and scientifically important resource deserving of protection, so he was always happy to give interviews and talk to local organizations.

In August 1954 Camp was interviewed about the ichthyosaurs by KRON’s Marjorie Trumbull on her Exclusively Yours television show.8 In June 1956 Camp appeared on Groucho Marx’s You Bet Your Life, however, the subject of ichthyosaurs may not have come up on that program.9

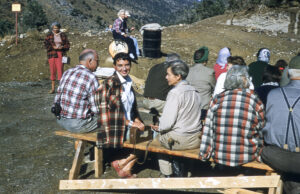

Thanks to all the publicity, Camp had to entertain and provide tours to a steady stream of curious Nevadans and tourists at the remote West Union Canyon site, with the biggest crowds arriving on the weekends.

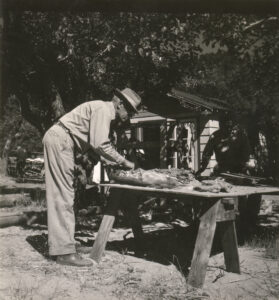

Sandblasting the bones, 1955

Camp discovered early on that the limestone matrix tended to adhere to the ichthyosaur bones, making it difficult to tell bone from rock and obscuring the true shape of the bones. He was determined to find a way to remove the limestone film; he tried turning a welding torch on the bones (with poor results) and considered pouring gasoline on them and lighting it. In the end, he found that sandblasting was the most effective way to remove the limestone. Camp wrote “Found to our pleasure that the sand will cut away the matrix … very rapidly and cleanly and will leave the bone in pristine condition—equal to the best weathering and better than any other method known to me.”10

So in 1955 he obtained the necessary equipment and, with Harold Newman and his son doing most of the labor, had all the bones in Quarry 2 cleaned up. Camp noted that “… the sand does a nice job of cleaning leaving a fine blue clean surface of fresh bone”11 that contrasted nicely with the surrounding limestone matrix. This made for a much more impressive in situ display.

Not only did Harold Newman provide the air compressor, but he and his son, Harold Jr., did practically all the sandblasting. They could only work about four hours a day “on account of the dust and heat of the respirator” as Camp wrote in his field notes. A few different kinds of sand were tested, but the best kind turned out to be a quartz sand that they collected from mine tailings near Ione to the north. A compressed air chipping hammer was used to remove the hardest matrix.

Protecting the fossils

West Union Canyon was within Toiyabe National Forest, Federal Government land, so the Nevada State Park Commission had to ask for a special use permit for the purpose of protecting the ichthyosaur fossils. The permit was granted in January 1955 and it was probably at this time that the area was designated Ichthyosaur Paleontological State Monument.

Governor Charles H. Russell visited the ichthyosaur site in 1956 and, as Camp put it, was “… satisfied that this place is worth preserving for exhibition purposes.”12 So when a statute was passed in 1957 giving the Governor greater powers to create parks, he wasted little time in granting the ichthyosaur site State Park status. But it wasn’t until 1970 that the State was able to acquire the ghost town of Berlin and create what we know today as Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park.

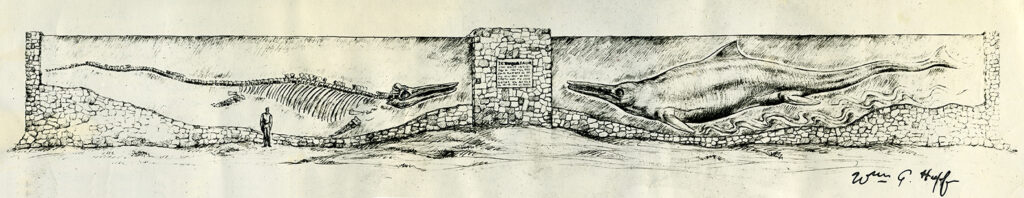

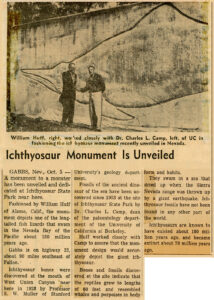

A full-size reconstruction, 1957

Camp invited his friend, sculptor William Gordon Huff, to create two full-size bas reliefs of a West Union Canyon ichthyosaur—one would be of the skeleton and the other would be a fleshed-out reconstruction. State funding could only cover the cost of one relief so Huff opted to do the reconstruction.

Huff and an eager crew of young volunteers prepared the plaster mold for the full-size ichthyosaur between July 18 and August 29. Jim Tow, a carpenter, completed the forms for the concrete on September 9. Two days later, some 50 cubic yards of concrete were poured into the form. The relief was unveiled before a crowd of about 100 people on September 29.

Camp described the informal unveiling ceremony: “Dedicating included introduction of Bill Huff by me—his fine speech—a closing paragraph or two when the monster was unveiled by pulling a cord and Mrs. Margaret Wheat christened him Shoshonisaurus [Camp ultimately went with the name Shonisaurus] with an old bottle filled with Pacific Ocean water.”13

Honoring Charles Camp, August 1961

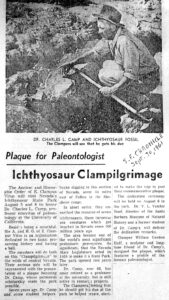

Charles Camp was a member of the Ancient and Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus (ECV), a fraternal organization dedicated to the study and preservation of the American West that can trace its roots to California’s gold rush days. ECV has placed many historical plaques throughout the West, often at sites overlooked by more traditional historical societies.

William Gordon Huff was a fellow Clamper and the Order’s most prolific creator of plaques. Huff made a plaque for the Nevada and California chapters of ECV to celebrate Camp’s efforts at the ichthyosaur site. A dedication ceremony was held on August 6, 1961. The ECV would dedicate the same plaque twice more before finding a permanent base for its mounting at the park.

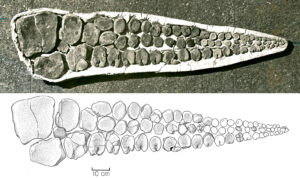

Collecting the best specimen, October 1963

Camp and Lester Kent spent almost two weeks in October 1963 at Quarry 5 excavating and jacketing the most complete ichthyosaur skeleton found at the West Union Canyon site. Camp drew a sketch of the specimen and indicated where they’d divide the skeleton into manageable chunks. With this sketch to guide them, the two went to work and ended up with more than 20 plaster-jacketed blocks, some weighing hundreds of pounds. The blocks were moved to an unused building in Berlin for safekeeping during the coming winter months.

Camp indicated in the last entry of his 1963 field notes, that he was thinking of submitting a proposal to the National Science Foundation for funds to prepare the ichthyosaur fossils.14

Preparation (1965-1967) & description

Camp arranged for the ichthyosaur fossils that had been stored in Berlin to be transported to the Foresta Institute for Ocean and Mountain Studies at Washoe Pines Ranch, north of Carson City, Nevada.

Here, for three summers, Camp—assisted primarily by his son Chuck and a high school boy, Willard Carmel—worked on the fossils.

They opened up all the plaster blocks, prepared and repaired the individual bones, and had them sandblasted and illustrated. During this period, Camp began writing his description of what was clearly a new species of ichthyosaur.

In 1967, at the end of Camp’s third season at the ranch, there was still some work to be done. He did make a quick trip to the West Union Canyon site the following year to take some measurements of bones at the Visitors’ Quarry, but he never returned to Washoe Pines Ranch. His own health had been in decline, and coupled with the death of his son Roderick in 1968, Camp would leave the completion of the project to someone else. Camp turned his manuscript over to UCMP’s Joe Gregory just a few weeks before he died in 1975 and the work was published under the title Large ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic of Nevada in 1980.

Dedication of the ichthyosaur shelter, 1966

Camp took time off from his work at Washoe Pines Ranch to attend the dedication of the new shelter at the Visitors’ Quarry, which he described as “… a noble structure well constructed.”15

The completion of the shelter provided the members of E Clampus Vitus with another excuse for a celebration and another opportunity to dedicate the Camp plaque that they had first dedicated five years earlier.

In his field notes, Camp had only this to say about the event: “The dedication of the shed took place at 2 pm. Dr. Leslie Gould spoke, Don Bowers spoke, Bob Hanson spoke on behalf of the Clampers. I spoke about the history of the region, etc.”16

The third and final dedication of the Camp plaque came in 1973, two years before Camp’s death. The plaque was permanently mounted at the Visitors’ Quarry at that time.

Publication of Camp’s ichthyosaur paper, 1980

When Camp turned his manuscript over to Joe Gregory, it was essentially complete. Gregory wrote that “The only serious gap in these materials was the lack of any measurements of the individual elements.”17 Josette Gourley had illustrated most of the ichthyosaur bones at Washoe Pines between 1965 and 1967 but Gregory found that there were some elements that she had not gotten to so he had UCMP illustrator Jaime Patricia Lufkin do these.

The fossils that Camp had left in storage at Washoe Pines Ranch remained there for ten years until they were transferred to the Museum of Natural History of the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. In 1999 they were moved to the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas, where they can be found today.

Incidentally, in 1977, two years after Camp’s death, Shonisaurus popularis was named the Nevada State Fossil.

Bonebed repairs, 1982-1984

In 1980, Sam Welles was contacted by Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park superintendent Mike McCormick who expressed his concern over the condition of the bonebed at the Visitors’ Quarry. After years of exposure to the air, the bones were beginning to disintegrate.

So Welles took advantage of UC Berkeley’s University Research Expeditions Program (UREP) and through that organization took groups of interested volunteers to the park over three consecutive summers to effect repairs.

His crews carefully cleaned the bones, removing residual limestone deposits where necessary, and then effectively sealed them with a brushed-on layer of vinac, a polyester resin dissolved in acetone. Welles also developed a new map of the quarry to assist park visitors in identifying the ichthyosaur bones.

During the work, Welles’ crews discovered two additional ichthyosaur skulls.

- Muller, S.W. 2008. Frozen in time: Permafrost and engineering problems. American Society of Civil Engineers. Page v.

- See the Biographical Note about Margaret Wheat. Retrieved 09/12/23.

- “Camp C.L., 1953-1954” field notes, page 4101; June 25, 1954, entry. UCMP Archives.

- Ibid. Page 4104; July 2, 1954, entry.

- From a description of the National Natural Landmarks Program. Retrieved 09/12/23.

- Clipping in the UCMP Archives; page 30 of the December 15, 1954, issue of Fortnight magazine.

- “Camp C.L., 1953-1954” field notes, page 4097; October 23, 1953, entry.

- Ibid. Page 4157; September 1, 1954, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1956” field notes, page 4307; June 13, 1956, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1953-1954” field notes; October 14, 1954, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1955” field notes; June 12, 1955, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1956” field notes, page 4324; July 21, 1956, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1957” field notes, page 4415; September 29, 1957, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1960-1965” field notes, page 4741; October 20, 1963, entry.

- “Camp C.L., 1966-1968” field notes, page 4847; July 3, 1966, entry.

- Ibid. Page 4891; August 20, 1966, entry.

- From the Foreword, page 140, of Camp, C.L. 1980. Large ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic of Nevada. Paleontographica, Abteilung A 170:139-200.