By 1910, Professor John C. Merriam had sent at least six expeditions to Shasta County, but sadly, a detailed account exists for only one of them: the 1902 expedition, and this account resides in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology’s Archives on the third floor of the Valley Life Sciences Building (VLSB).1

The Shasta County Expedition, 1902

by David K. Smith

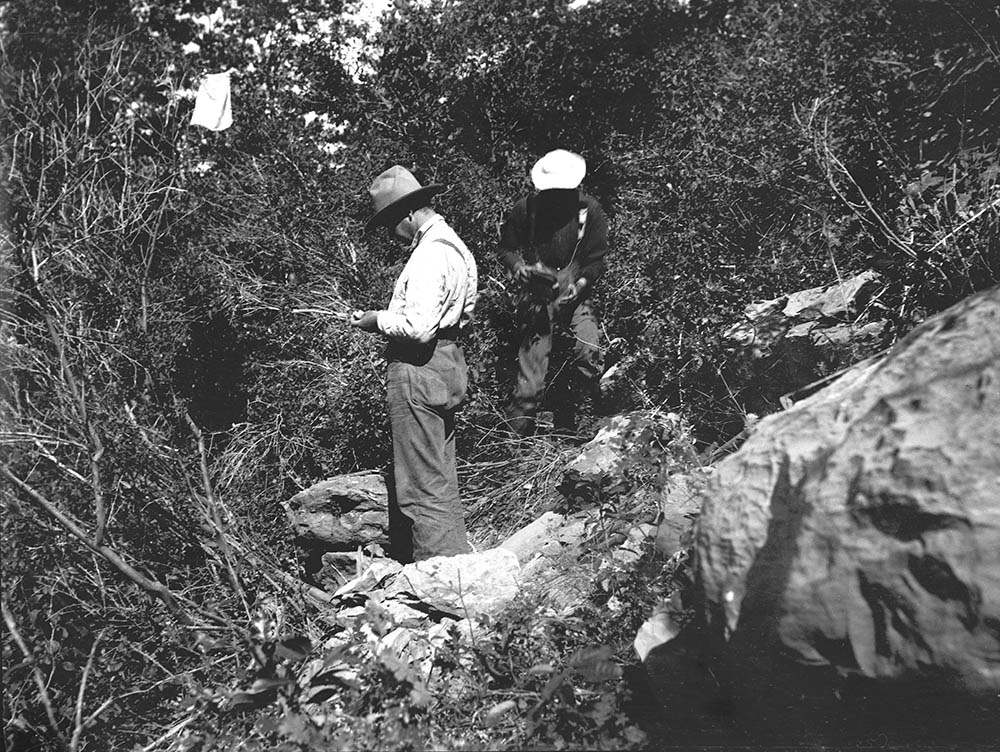

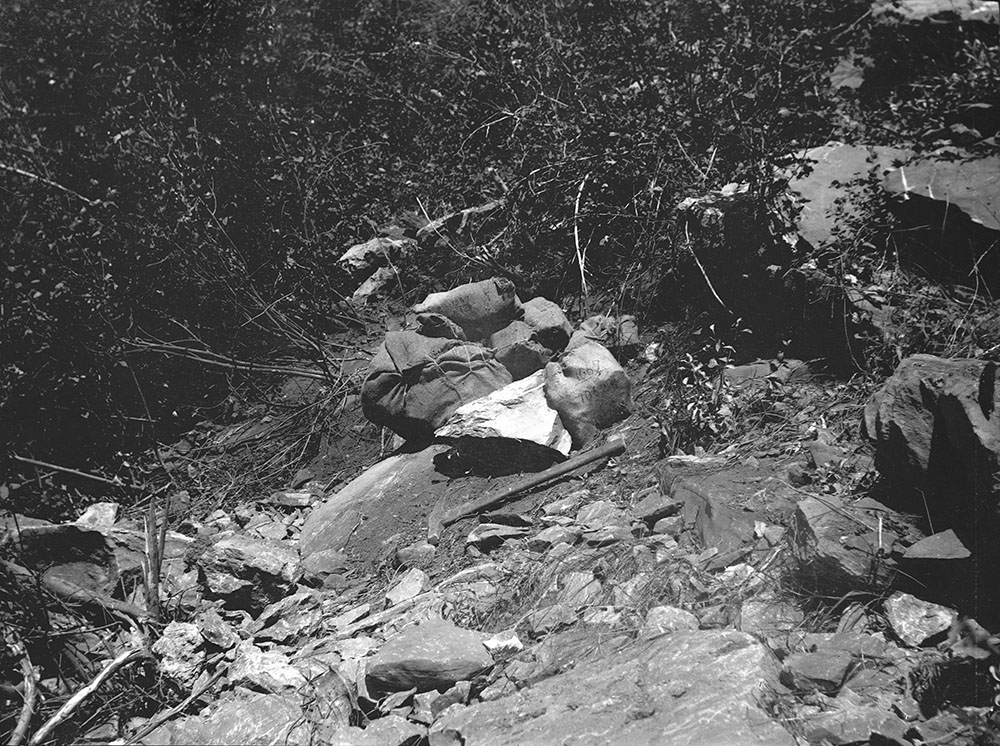

The 1902 expedition was not particularly long — the crew was in the field for just 28 days, June 16 to July 13 — nor did it cover much ground. The party focused most of its attention on a single limestone ridge between Squaw Creek and the Pit River. The six-person crew was led initially by Vance Osmont, a 28-year-old former Assistant in Geology and student of Merriam’s at Berkeley. Merriam took charge when he arrived two weeks into the expedition. The other male members of the crew were Eustace Furlong and Waldemar Schaller. Annie Alexander invited a UC Berkeley acquaintance, Katherine Jones, to join her. It was Ms. Jones who kept the account of the expedition.

Although a significant number of marine reptile fossils were recovered, this expedition may be more interesting in terms of California history, in both the towns visited and the people encountered. Read Ms. Jones’s notes — the link to the pdf follows — before moving on to an examination of some of the interesting aspects of this expedition.

View the pdf of the 1902 Shasta County Expedition

Observations regarding Ms. Jones’s notes

Annie Alexander and Katherine Jones left from and returned to Oakland via the 16th Street train station at 1601 Wood Street. At that time the train tracks were right on the San Francisco Bay shoreline, but since then, the shoreline has been filled in considerably so that now it’s about a mile west of the station. The original station was a wooden structure; it was replaced with a Beaux-Arts building designed by architect Jarvis Hunt in 1912. The station had not been used since 1994 but has been restored as part of a redevelopment project. The station can now be rented for private events.

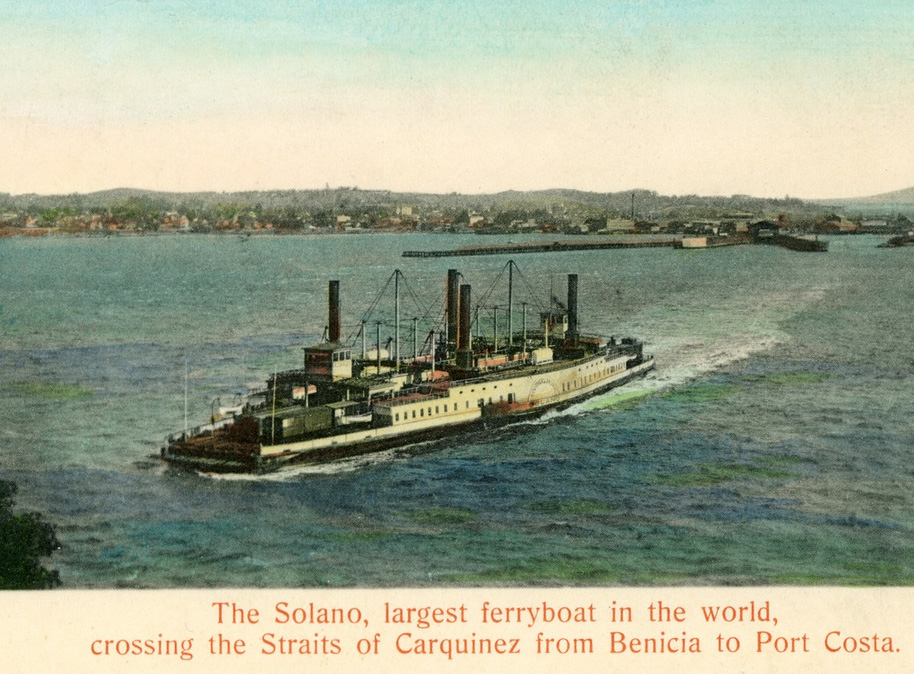

Once on the train, Katherine noted that “At Port Costa we found that the Solano was out for repairs, so we had to go by way of Stockton.” It wasn’t until 1930 that a railroad bridge was built across the Carquinez Strait connecting Martinez and Benicia so, between 1879 and 1930, entire trains — even 48-car freight trains — were ferried across the channel, from Port Costa to Martinez. The distance from dock to dock was one mile and the trip took about nine minutes. Until 1914 when a second rail ferry was built, the Solano was the largest ferryboat ever built at 425 feet long and 116 feet wide. See many pictures of the ferry and docks and check out the Wikipedia entry.

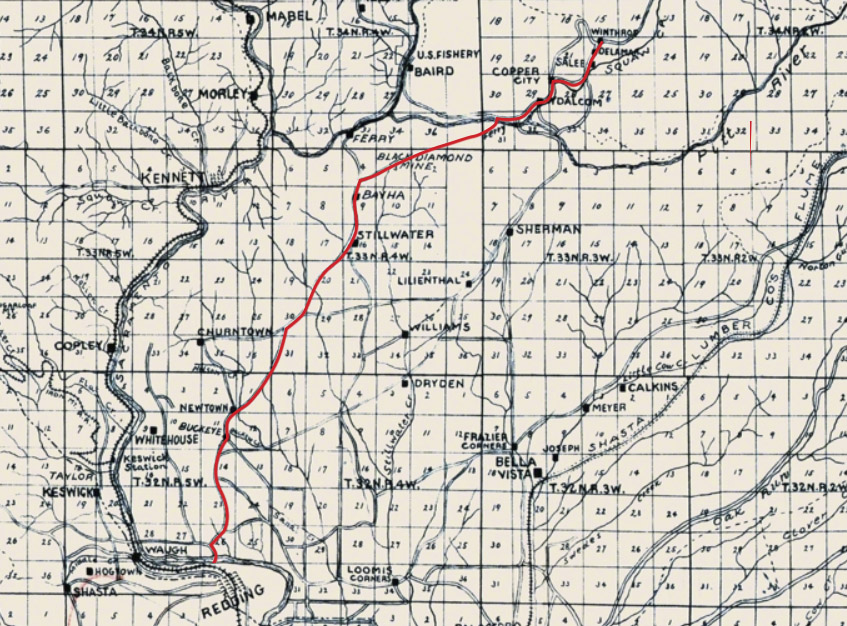

Annie and Katherine took the train as far as Redding and then covered the remaining 25 miles or so to Winthrop by horse and carriage. Vance Osmont was waiting for them there. The town of Winthrop no longer exists today, having been flooded following construction of the Shasta Dam. The town was originally located along Squaw Creek, a little north of the Bully Hill Mine, and is now under the Squaw Creek Arm of Shasta Lake. A few photos of Winthrop can be viewed on the Shasta Historical Society website.2

After having lunch, Annie, Katherine and Vance set out for the home of a Mr. Matteson — later on in the notes the name is changed to Madison, the correct spelling. Madison’s Ranch may be where the expedition acquired its horses; it certainly obtained most of its provisions there. Madison’s place, a few miles north of Winthrop, probably met the same fate as the town but the rancher is not forgotten; Madison Gulch and Madison Canyon are features on modern maps. A photo of the Madison Ranch can be viewed on the Shasta Historical Society website.3

In Ms. Jones’s June 21 entry, she left Mr. Madison’s place for the town of “De Lemar” or Delamar as most sources spell it. The town was founded (as was Winthrop) just two years before the expedition arrived to serve the booming Bully Hill Mine just up the hill. At its peak, the mine employed some 2,000 people and the town’s population was almost three times that. Like Winthrop, which was just to the north, much of Delamar now lies beneath the waters of Shasta Lake’s Squaw Creek Arm but some of it reportedly can be seen along the shoreline. It was named for New York billionaire Captain Joseph Raphael De Lamar (1843-1918) who bought the Bully Hill Mine. Significant amounts of copper, gold, silver and zinc were extracted from Delamar’s mines before (and after) they were sold to the General Electric Company in 1905. Several photos relating to the Bully Hill Mine can be seen on the Shasta Historical Society website.4

On the Shasta Historical Society website there is a photo of downtown Delamar, presumably taken on the 4th of July, 1902; the UCMP crew was collecting fossils just a few miles to the east. Five days later, a fire that began in a saloon destroyed 15 Delamar homes. It’s surprising that Ms. Jones did not mention it in her notes; Furlong had gone to Madison’s on the 10th and the fire would have been big news.5

Along with Madison, another man named Kelley (sometimes spelled Kelly) is referred to a few times in Ms. Jones’s notes (July 6, 11, 12 and 18 entries). Both men had ranches along Squaw Creek; David Brock’s ranch was on the Pit River. All three of these ranches must have been well established because in the scientific literature, directions to localities are often given in relation to their distance from one or more of the ranches. For example, James Perrin Smith says in one paper “These Triassic limestones and slates extend from Brock’s Ranch on Pit River northward about thirty miles, crossing Squaw Creek west of Kelly’s Ranch near the forks of Squaw Creek.” In another he says “It [the ammonite Juvavites subintermittens] was also found by the writer on the west side of the North Fork of Squaw Creek, Shasta County, 3 miles north of Kelly’s ranch, and 15 miles northeast of Madison’s ranch.”6

While in Delamar on June 21, Ms. Jones visited the Baumann Hotel. See a photo of the hotel on the Shasta Historical Society website.

David Brock is first mentioned in the June 24 entry. Like Mr. Madison, the Brock name carried enough weight to warrant the naming of geographical features. Both Merriam and Smith collected many of their fossils on Brock Mountain, Brock Butte is about seven miles northeast of the mountain, and Brock Creek flows south into the Pit River Arm of Shasta Lake. No geographical feature has Kelley’s name on it, however, the Kelley Ranch may still exist. It was located near the point where the North Fork of Squaw Creek branches off from the main channel, far enough upstream to be unaffected by the flooding of Shasta Lake. On Google Maps (satellite view), one can see that a ranch is still located near the fork. There is a tributary of Squaw Creek named Smith Creek — could it have been named for James Perrin Smith?7

In Ms. Jones’s June 27 entry, Merriam mentions to Amanda Brock, David’s mother, that he’d read in the newspaper about the death of Joaquin Miller’s daughter. Amanda was so afraid that it was the daughter she’d had by Miller, but it turned out to be Maud, another of Miller’s girls. Maud died in December 1901.8

The July 1 entry mentions “drilling holes for the giant powder.” The Giant Powder Company was a Bay Area dynamite manufacturer that in 1902 was located at Point Pinole; ruins of the place are still visible at Point Pinole Regional Shoreline. Before moving to Point Pinole, the company was located in Albany near today’s Golden Gate Fields. An explosion at the plant in 1892 shattered windows for miles around, including those on the University of California campus.9

The July 2 entry mentions looking for the “trail to Cherrup Cherra.” A week later Ms. Jones spells it “Cherrup Chata.” It turns out that neither of these spellings may be correct. In publications by James Perrin Smith, he refers to the place, also known as Cottonwood Flat, as Terrup Chetta (sometimes it’s hyphenated). But then the UCMP collections database spells it Terrup Chata and a USGS publication from 1901 has it as Terrup Chatta. It was reported to be on Squaw Creek about six miles northeast of Madison’s Ranch.10

The July 13 entry begins “No further notes written up ….” This suggests that some member of the party — probably Merriam or Osmont — had been keeping field notes but where they are today is a mystery. There are no field notes from Osmont, Schaller or Furlong in the UCMP Archives; Merriam probably took most of his field notes — and perhaps those of others if they concerned material that interested him — when he left the University for the Carnegie Institute of Washington, D.C., in 1921.

Participant profiles and people encountered

KATHERINE DAVIES JONES (1860-1943)

Jones was born July 1, 1860, to Welsh parents in Wisconsin where she may have been home-schooled. She moved to Berkeley to attend the University of California and she earned a Ph.B. (Bachelor of Philosophy) degree in 1896. Afterwards, she began working at the University and remained there for at least 33 years; she was still employed there when she was 69. She held various positions such as stenographer, assistant and curator before becoming an instructor.

In the MVZ Archives, there is a 1934 letter from MVZ Director Joseph Grinnell addressed to Jones in Agriculture Hall (now called Wellman Hall), one of the buildings housing the College of Agriculture (now the College of Natural Resources). It’s not too surprising that Jones would be working there since she was clearly interested in — and knowledgeable about — the plants and animals encountered during the expedition.

Jones never married nor did she buy a place of her own; she lived in boarding houses and rented apartments her entire adult life. She died in 1943 and is buried in Sunset View Cemetery in El Cerrito. The only other tidbit about Jones that could be discovered is that she was a Second Soprano in the University of California Women’s Choral Society, according to the 1905 and 1906 Blue and Gold yearbooks.11

VANCE CRAIGMILES OSMONT (1874-1943)

Osmont was born in Tennessee on May 3, 1874, to Thomas Melmoth Osmont (1841-1905), a lawyer, and Augusta C. Craigmiles (1846-1931). He had a younger sister, Adelia R. Osmont (1876-1971).

Osmont grew up in Cleveland, Tennessee, but he moved to the Bay Area to attend the University of California in 1894. Not only was Vance a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, but he and Harry J. Cox of Stanford founded the Cal Beta Chapter that year. He was also a member of the Gun Club. As a senior, during the 1899-1900 academic year, Osmont was an Assistant in Geology and helped teach a couple lab courses. Osmont received his B.S. in mining in 1900. After graduating, he apparently continued to participate in Merriam’s field expeditions and was again an Assistant in Geology for the 1903-1904 academic year. In 1903, he was offered a professorship of dynamic geology at the University of Nevada but apparently turned it down. In 1904 Osmont published a paper entitled A Geological Section of the Coast Ranges North of the Bay of San Francisco in the University of California’s Bulletin of the Department of Geology. He probably left the university around this time and went into business as a mining engineer. In 1907 he was a partner in Daniels & Osmont, a landscape engineering business, in San Francisco; later, Daniels, Osmont & Wilhelm. Daniels (Mark Daniels) was responsible for the the layout of streets in the Thousand Oaks neighborhood of Berkeley as well as the Bel-Air neighborhood of Los Angeles and the 17-mile-drive in Monterey.

Vance married Mary Peirce Hall on April 2, 1908, and they had two children, Vance C. Osmont Jr. (1911-1963) and Betty Osmont (1878-1960). Osmont lived in the Bay Area, primarily the East Bay, for the rest of his life. For a time he stayed at the Key Route Inn in Oakland but he also lived at a number of different addresses in Berkeley and Oakland, finally ending up in Piedmont. Vance died in Alameda County on Feb 8, 1943, and is buried at Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma.12

WALDEMAR THEODORE SCHALLER (1882-1967)

From Katherine Jones’s notes, one gets the impression that Mr. Schaller was not cut out for paleontological field work. That may be, but that didn’t stop him from becoming a notable mineralogist/chemist/geologist in his later years.

Schaller was born in Oakland, California, on August 3, 1862, to Theodore Phillip Schaller (1846-1918), a German merchant, and Elizabeth Bovnemann (1848-1938) of Denmark. He had three brothers: Edwin John Schaller (1875-?), Hugh Bayard Schaller (1879-1880) and Oliver Schaller (?).

He attended public schools in Oakland and San Francisco before studying geology at the University of California under Andrew C. Lawson and Arthur S. Eakle. Schaller lived with his parents in San Francisco during his undergraduate years. After graduating in 1903, he went to work for the Division of Chemical and Physical Research of the United States Geological Survey. He took a break in 1912 to work on his Ph.D. under Paul von Groth in Munich; he earned that degree before the end of the year. Schaller returned to working with the USGS and served as Managing Director of the Chemistry and Physics Division between 1944 and 1947.

Schaller apparently moved to Washington, D.C., when he began working with the USGS and he was to remain in that city for the rest of his life. He married Mary E. Boyland there in August 1908. Schaller remained at the USGS until he became ill in 1965 at the age of 83. He died two years later at the Mar Salle Nursing Home in Washington, D.C.

Schaller was a member of several scientific societies and held important positions with some of them. These included the Mineralogical Society of America, the Geological Society of Washington, the Washington Academy of Sciences, the Mineralogical Society of Great Britain and Ireland, the Vienna Mineralogical Society, American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Chemical Society, Geological Society of America, American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Washington Academy of Sciences, Deutsche Mineralogische Gesellschaft, Société Française de Mineralogie, Wiener Mineralogische Gesellschaft, Sigma Xi , the Cosmos Club, and was an honorary member of the New York Mineralogical Club. Schaller authored 148 papers and reports.13

The German Wikipedia page on Schaller describes some of his achievements:

Schaller’s contributions to mineralogy were numerous, covering a wide range of topics. Above all, his conclusion that water or hydroxyl is an indispensable component of tremolite can be regarded as outstanding, which led to a new interpretation of the composition and structure of all amphiboles. Likewise, his studies on the paragenesis of the salt minerals and their deposits in New Mexico and Texas from the Permian period were groundbreaking for the British mineralogists and their later investigations of the English evaporites of the same age.

JOSEPH SILAS DILLER (1850-1928)

Diller was not a member of any University of California expedition but he did pay a visit to the Berkeley crews’ camps both during the 1902 Shasta County and the 1901 Fossil Lake expeditions. For this reason, it’s fitting to say a bit about him. He was a prominent geologist who, like Schaller, spent many years with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), but unlike the mineralogist, he was quite at home in the field.

Joseph Silas Diller was born August 27, 1850, in Plainfield, Pennsylvania, to Samuel Diller (1813-1879), a farmer, and Catherine Bear (1816-1885). He had two brothers, John Bear Diller (1841-1902) and William Henry Diller (1846-1906). Diller married Laura Paul on June 5, 1883, in Greason, Pennsylvania, but I suspect that Laura was alone much of her married life since her husband spent so much time in the field. One can read up on Diller’s life and accomplishments on the Crater Lake Institute website but it should be noted that the man is best known for his work on Crater Lake. With Horace B. Patton, Diller published a paper on The Geology and Petrography of Crater Lake National Park in 1902, the same year the park was established. This was the definitive paper (and the first) on the origin and geology of Crater Lake. Diller was with a USGS crew at the lake when Annie Alexander and the Berkeley crew encountered him in 1901.

Since the orphaned USGS Menlo Park Invertebrate Collection has now been integrated into UCMP’s collections, Berkeley now can say that it has fossils that were collected by Joseph Diller. During the integration process, Museum Scientist Erica Clites wrote a blog post about the encounter between Annie Alexander and Diller during the Shasta County expedition; there’s also a photo of a fossil collected by Diller in 1899. See Encounters in the Field: UCMP and the US Geological Survey.14

DAVID SOLOMON BROCK (~1870-1927)

David Solomon Brock was born between 1868 and 1872 in California, probably Shasta County, to James Brock (1830-1897) of Indiana and Amanda (her English name) Brock (1834-1909) of the Native American tribe that lived along the McCloud River, Shasta County, California.

U.S. Census information shows that Brock worked for the Tucson Division of the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1917 and was a laborer for the State Highway System in 1920. He married a woman named Matilda, probably a Native American, who could neither read nor write and was 24 years his senior.

David died on April 10, 1927, in Shasta County and is buried in the Central Valley Cemetery at Shasta Lake, probably near his mother’s grave. Amanda’s remains were originally interred at the New Campbell Cemetery but were moved to the Central Valley Cemetery in 1942 because of the impending flooding of Shasta Lake.15

AMANDA BROCK (1834-1909) AND HER DAUGHTER

The most interesting character in Jones’s notes is unquestionably Amanda, who claimed to be the ex-wife of poet Joaquin Miller and the mother of a daughter by him. She was definitely someone with a history to be examined more closely. Amanda and Joaquin probably were not legally married but there is no doubt that they did have a daughter.

The following excerpt from Alan Rosenus’s afterword in Heyday Press’s 1996 reissue of Miller’s Life Amongst the Modocs provides a good description of the relationship between Amanda and Miller:

Early in the winter of 1856, he [Miller] set up housekeeping with a McCloud Indian woman named Sutatot [the name Miller used for Amanda] in Squaw Valley between the Upper Sacramento and McCloud Rivers. Sutatot would one day serve as a model for Paquita, the Indian heroine of Life Amongst the Modocs.

We know that Miller and Sutatot had a daughter named Cali-Shasta, and years later, while he was away (probably in Oregon), the mother and daughter were captured by Modocs and lived in slavery until rescued by a scout named Jim Brock. Sutatot married Brock, had children by him [David being one of them], and was thereafter known to Californians as Amanda Brock. In 1872, Miller escorted Cali-Shasta from northern California to San Francisco to complete her education, placing her in the care of Ina Coolbrith. Almost forty years later, Cali-Shasta’s mother, Amanda Brock, was still enough of a celebrity to have her death reported in the San Francisco newspapers. Her age at the time was said to be seventy-five years. This meant Amanda was about three years older than Miller when they began living together on the McCloud.

Much of her life with Miller was occupied with cooking and storing foods. She also helped him prospect for gold between snowfalls. When food was scarce, he crossed across the mountains to the white communities on the Upper Sacramento to obtain supplies. (Hardly a model husband for very long, by August of this same year, during a trip north to Eugene, Miller was attracted to a Miss Mary J. Tompkins of Willamette Forks and wrote her a love letter).16

As Rosenus said, the San Francisco newspapers wrote of Amanda’s death. The June 9, 1909, issue of the San Francisco Call had this to say:

POET JOAQUIN MILLER’S INDIAN WIFE IS DEAD

Buried on McCloud River With the Rites of Her Tribe

REDDING, June 8. – Amanda Brock, an Indian woman aged 75 years, died Monday afternoon at her home on McCloud river. She was an Indian with a history.She was the first wife of Joaquin Miller, the poet, and while living with him she was made a captive by a band of Modoc Indians for many years, and she was held prisoner and escaped with the aid of Bill Brock [sic], a white scout, whom she married and has since lived with.

The Indian woman was buried Tuesday afternoon in the Indian burial grounds on the McCloud. The Indians for miles around gathered and the ceremony was conducted with the regular rites of her tribe.

The following day, the Santa Ana [California] Register reported:

ROMANCE SHATTERED BY JOAQUIN MILLER

San Francisco, June 10. – The romantic story of the early marriage of Joaquin Miller to Sutatot Shasta, an Indian woman, was denied today by Miller.Miller said he regarded her as a heroine and as his best and truest friend. He paid a tribute to her character and her womanliness, and also said that Sutatot saved his life after a fight with the Modocs. Later she married Jim Brock, the noted scout. She died yesterday.

But what about Cali-Shasta Miller, the girl whose name Ms. Jones recorded in her notes as “Carlante (Carlanto?)”? What became of her? Rosenus said that Miller placed the girl in the care of Ina Coolbrith, another Bay Area poet.

Ina Coolbrith (1841-1928) was the niece of Joseph Smith, founder of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and became California’s first Poet Laureate in 1919. There is an extensive Wikipedia page on Coolbrith that one should consult for more information but it is worth noting that it was Coolbrith who turned Joaquin Miller into a celebrity; she suggested that he adopt that pen name (his real name was Cincinnatus Hiner) and to start dressing the part of a mountain man. Coolbrith hobnobbed with many of the best known writers and poets of her day, including Bret Harte, Samuel Clemens, Alfred Lord Tennyson, John Muir, Charles Warren Stoddard, Ambrose Bierce, and Jack London (she was his mentor). Coolbrith served as a librarian at the Oakland Public Library for 19 years (1874-1893).

A blog post by Aleta George, Coolbrith’s biographer, tells the story of what became of Cali-Shasta, or Calla Shasta as Ms. Miller referred to herself:

While visiting Miller’s former homestead in the hills above Oakland [Joaquin Miller Park], I will remember his daughter, Calla Shasta Miller, who is buried somewhere on the grounds in an unmarked grave.

Calla Shasta lived with Ina Coolbrith for a decade while Joaquin was pursuing his career in England and New York.

The young woman eventually married, but she returned to Ina’s Oakland home in 1892, her marriage over. Ina told Charles Warren Stoddard that Calla Shasta came to her “homeless, helpless, and a victim to drink.”(2) Ina secured a doctor to try hypnotism and the Gold Cure, a popular abstinence program that purportedly contained gold, but in reality was a mixture of alcohol, ammonium, strychnine, and boric acid.

Calla Shasta did not stay at Ina’s house for long. She died in 1903 and Miller buried her in an unmarked grave on his property. [Coolbrith] asked a friend to look for Calla Shasta’s grave and vowed to mark “poor Indian Callie’s grave” if she ever could afford to. (3) Ina was not a woman of means, and she never did mark the grave. Ina’s own grave at the Mountain View Cemetery remained unmarked from the time of her death in 1928 until 1986 when the Ina Coolbrith Circle gave her a beautiful marble headstone [in Plot 11].17

The Shasta County expeditions were certainly important in terms of expanding our knowledge of the Triassic marine reptiles of California, but the people encountered and places visited, particularly in the case of the 1902 expedition, were fascinating in their own right.

- Information not obtained from Katherine Jones’s account will be specified as coming from other sources.

- See an excerpt from a Los Angeles Herald article on the fire. The fire is also mentioned on the Western Mining History website.

- Madison Gulch and Madison Canyon located on Google Maps.

- See pages 3 and 4 of a US Forest Service pdf on Sightseeing on Shasta Lake and a little underwater history. More information on Delamar, Captain De Lamar, Bully Hill and Delamar and Bully Hill mining history.

- See an excerpt from a Los Angeles Herald article on the fire. The fire is also mentioned on the Western Mining History website.

- First quote from page 363 of Smith, J.P. 1904. The Comparative Stratigraphy of the Marine Trias of Western America. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences: Geology, 3d series, 1(10):322-429. Second quote from page 59 of Smith, J.P. 1927. Upper Triassic Marine Invertebrate Faunas of North America. U.S. Geological Survey, Professional Paper No. 141. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 262 pp.

- Locate Brock Mountain, Brock Butte, and Brock Creek on Google Maps.

- Maud Miller’s death was announced in the January 2, 1902, issue of the Healdsburg [California] Enterprise. Also see joaquinmiller.com (once there, do a search for “Maud”).

- See the Wikipedia entry on the Giant Powder Company.

- The July 2 entry mentions looking for the “trail to Cherrup Cherra.” A week later Ms. Jones spells it “Cherrup Chata.” It turns out that neither of these spellings may be correct. In publications by James Perrin Smith, he refers to the place, also known as Cottonwood Flat, as Terrup Chetta (sometimes it’s hyphenated). But then the UCMP collections database spells it Terrup Chata and a USGS publication from 1901 has it as Terrup Chatta. It was reported to be on Squaw Creek about six miles northeast of Madison’s Ranch.

- Information from sources accessed on ancestry.com, including the University of California 1905 and 1906 Blue and Gold yearbooks.

- Family and other information from sources accessed on ancestry.com. At the time of the 1902 expedition, Hilton 2003 (see footnote 1 on the previous page) claims that Osmont was an Assistant Professor but I can find no evidence that he advanced beyond Assistant in Geology; see the University of California General Catalog for the 1903-1904 academic year, page 118. After graduating he appears to have had no official title in the Geology Department. Osmont’s paper: Osmont, V.C. 1904. A geological section of the Coast Ranges north of the Bay of San Francisco. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 4:39-87.

- Family and other information from sources accessed on ancestry.com, as well as American Mineralogist, vol. 24, pages 53-58, 1939.

- Family and other information from sources accessed on ancestry.com, as well as the Crater Lake Institute page noted in the text. The Diller and Patton paper: Diller, J.S., and H.B. Patton, The Geology and Petrography of Crater Lake National Park, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1902, 167 pp.

- Family and other information from sources accessed on ancestry.com.

- From Miller, J. 1996. Life Amongst the Modocs. Heyday Press. 434 pp. Originally published in 1873.

- The first quote is in a letter from Coolbrith to Charles Warren Stoddard, dated August 15, 1892. From The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. The second quote is in a letter from Coolbrith to Herbert Bashford, dated February 25, 1913. From The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.