The Shasta County Expeditions, 1901

by David K. Smith

John C. Merriam, professor of paleontology in UC Berkeley’s Department of Geology, organized a number of fossil-collecting expeditions to Shasta County in the early 1900s. There were two in 1901 (one in the summer and one in the fall) and one each in 1902, 1903, 1906 and 1910 (the last two will not be discussed here); there may have been others of which I am unaware.1

The UCMP archives contain no field notes of any of the expeditions that traveled up to Shasta County, however, the museum’s Supplemental Locality Files contain 32 negatives, three photographs and a couple drawings, and there are 14 Shasta County negatives in the Large Format Negative Collection. There are no dates on the negatives and prints but some are clearly from 1901 (see the photos of UCMP 9119 below).

The best account of any of the Shasta County expeditions can be found in the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) on the third floor of the Valley Life Sciences Building. They have a typed copy of fairly detailed notes kept by one Katherine Jones during the 1902 trip. Jones’s notes provide a fascinating record of what an early Berkeley paleontological field expedition was like; see the companion page on this expedition.2

There isn’t a lot of information on the two 1901 expeditions or on the 1903 one — we don’t even know the names of most of the 1901 participants — but a few tidbits can be gleaned from Merriam’s publications and correspondence. Katherine Jones’s 1902 notes make a couple of references to the summer 1901 trip.

At the time of the summer 1901 trip, Annie Alexander was on her Fossil Lake Expedition in Oregon. Although she did not go up to Shasta County in the fall, she financed that trip and probably the 1902 and 1903 ones as well; she did participate in these latter two, making significant discoveries. A number of the participants in these expeditions have been profiled elsewhere in the UCMP History pages, but the newcomers will be profiled in these Shasta County pages.

Why Shasta County?

The origins of UC Berkeley’s Shasta County expeditions can be traced to 1893 when Stanford University’s James Perrin Smith went looking for ammonites in the Triassic Hosselkus Limestone of northern California, primarily along a ridge running roughly north-south between Squaw Creek and the Pit River. He was successful in finding many ammonites, however, he also came upon the bones of a marine reptile that he attributed to Nothosaurus. These were the first Mesozoic marine vertebrate remains found in California.3

In the spring of 1895 Smith sent the bones he’d found to Merriam in Berkeley and the latter determined that the bones were of a reptile similar to ichthyosaurs, proposing the name Shastasaurus pacificus. Merriam now wanted to see the Shasta County locality himself and perhaps obtain more specimens.4

By 1908 Merriam had sent at least five collecting expeditions to Shasta County and had already published papers on several of the recovered vertebrate specimens, which included ichthyosaurs and thalattosaurs. That year he published his Triassic Ichthyosauria, with Special Reference to the American Forms in which he described the ichthyosaur material collected:

The material upon which the studies of the American Triassic ichthyosaurs are based includes over fifty specimens, each of which represents a considerable part of the skeleton; also a large quantity of more fragmentary material. These collections have been brought together by ten expeditions [some were to Nevada] sent out by the University of California between 1901 and 1907. 5

Although fewer in number, the thalattosaur specimens collected were important in that they represented a previously unknown kind of marine reptile. Merriam described the type species in 1904 and followed that up with a full description of the group a year later. The type specimen was named Thalattosaurus alexandrae in honor of Annie Alexander. Merriam noted that Annie “was herself the discoverer of the type specimen furnishing the largest part of our information concerning the group.” 6

The 1902 expedition, with its much richer record and interesting aspects, is discussed here.

The 1901 expeditions

In Merriam’s 1902 publication on the Triassic Ichthyopterygia from California and Nevada he reported that in the summer of 1901, he traveled up to Shasta County accompanied by Smith and a group of students from both Stanford and Berkeley. There is no record of who those students were. The trip was successful and a good deal of material was collected, however, the party was ill-equipped to recover some of the larger bone-bearing slabs of rock, so this is why Merriam sent out a second party in the fall.7

The summer expedition camped at Madison’s Ranch on Squaw Creek. This is mentioned in the June 21 entry of the notes taken by Katherine Jones a year later. She wrote:

We walked to Mr. Matteson’s [Madison’s] and sat under the same tree that the Professor James Perrin Smith party of the year before used to sit and smoke under every day because it was half way down from the cove [Smith Cove] to their camp at Matteson’s [Madison’s]. This party went up that trail every day for fossils and walked back again at night. This was done to please Professor Smith of Stanford who wished to reduce his weight. It is 2½ miles up the mountain trail and was enough to kill the men. Even Professor Smith had enough of it in six days.

Whether the party decided to move its camp at that point is unknown.

The fall trip, which lasted about eight weeks, was led by Herbert Furlong; the other participants in the expedition are unknown. Furlong had only recently returned from the 11-week Fossil Lake Expedition with Annie Alexander. 1901 was a busy year for Furlong, however, the Shasta County trip would be his last venture on Merriam’s behalf; the following year, his younger brother Eustace would take over Herbert’s role. But it’s likely that the Furlong brothers’ time in the Merriam Lab overlapped for at least the latter half of 1901 because Eustace was probably already at work preparing the Shasta County specimens.

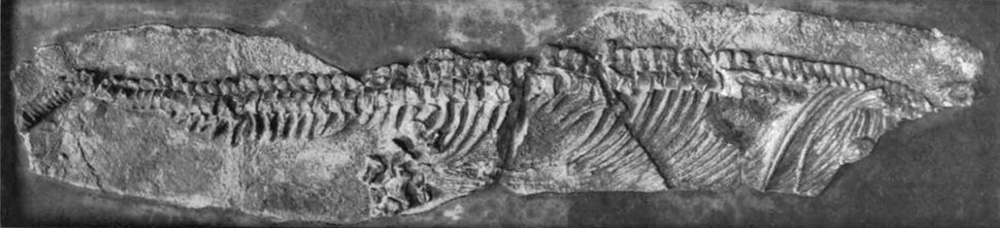

One of the large specimens discovered in the summer was of Shastasaurus osmonti (UCMP 9076). Merriam has this to say about it:

The type material of this species includes thirty-five vertebrae with the most important parts of the anterior arch and limbs. It was discovered by Mr. V.C. Osmont in the limestones near the Cove [Smith Cove] in June, 1901. About half of the bones, including the right limb, were embedded in several loose slabs lying at the foot of a limestone cliff, from which they had evidently but recently been separated, as other vertebrae and ribs were seen protruding from the rock close to them. The remains in the solid rock of the cliff were worked out in the fall of 1901 by Mr. H.W. Furlong, and were found to include part of a left limb of exactly the same dimensions as the right limb in the loose slab. The coracoids, and many of the cervical vertebrae, were found with the left limb. There can be no doubt that all of these remains belong to the one animal. 8

Osmont participated in the 1902 expedition and the 1901 specimen he found is mentioned in Katherine Jones’s notes, the June 17 entry: “On the way home we saw the point where Shastasaurus Osmonti [sic] had been found — the two specimens. Mr. O. [Osmont] found some broken fragments of the rocks and afterwards the larger pieces in the cliffs above. It was exciting work getting such a big find. We envied Mr. O. as he told his tale.”

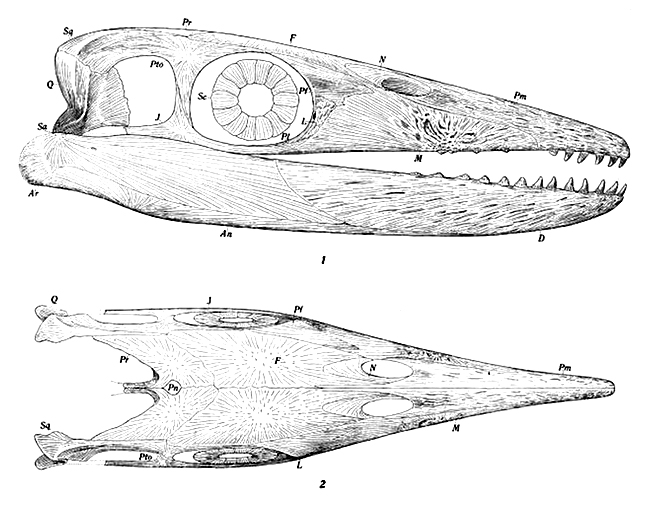

Another specimen, this one of Shastasaurus alexandrae (UCMP 9017; again, named for Annie Alexander), was “collected … by the party under Mr. H.W. Furlong. … The specimen includes the greater part of a skull, nearly all of the pectoral girdle, part of a humerus, fifteen or sixteen vertebrae belonging to the anterior portion of the column, and numerous ribs.”9

And another large specimen recovered in the fall was Merriam’s Shastasaurus perrini (UCMP 9119; named for James Perrin Smith) that exhibited “an unbroken series of eighty vertebrae.” The specimen had been found a few years earlier by Smith but he “generously turned it over to the University of California party.” In 1905, Merriam decided that S. perrini was different enough from Shastasaurus to merit a new genus, Delphinosaurus. It turned out that the name Delphinosaurus was already in use so the name Californosaurus was assigned; this is the name that is generally accepted today. The UCMP database describes UCMP 9119 as Toretocnemus but this should probably be changed.10

- Expedition years from Hilton, R.P. 2003. Dinosaurs and other Mesozoic reptiles of California. University of California Press, Berkeley. 318 pp. See pages 129-143.

- Regarding MVZ’s copy of Jones’s notes, in 1934 MVZ’s Joseph Grinnell wrote to Jones following a conversation with her about having a copy made for the museum. “If you will deliver them [the notes] to his [a messenger’s] care, we will have them copied and return the original to you quite soon.” So the copy now in the MVZ archives was typed by an unknown person at the museum in 1934. A pdf of this typed document can be viewed online. Grinnell letter from the MVZ Archives.

- Regarding the Hosselkus Limestone, University of California officials in the late 1960s, citing the area’s paleontological importance, urged the state to provide an extra layer of protection to the area. In 1997 the area between the Squaw Creek and Pit River Arms of Shasta Lake was designated as the Devils Rock-Hosselkus Research Natural Area. See the Management Guide for the Shasta and Trinity Units of Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area, page 2-24.

- Merriam, J.C. 1895. On some Reptilian Remains from the Triassic of Northern California. American Journal of Science, 2d series 50(395):55-57.

- Merriam, J.C. 1908. Triassic Ichthyosauria, with Special Reference to the American Forms. Memoirs of the University of California 1(1):1-196

- Merriam, J.C. 1904. A New Marine Reptile from the Triassic of California. University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geology 3(21):419-421.

- Merriam, J.C. 1902. Triassic Ichthyopterygia from California and Nevada. University of California Publications, Bulletin of the Department of Geology 3(4):63-108.

- Ibid. Pages 93-94.

- Ibid. Page 96.

- Quotes are from Merriam 1902, page 89. The thalattosaur paper is Merriam, J.C. 1905. The Thalattosauria: A Group of Marine Reptiles from the Triassic of California. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences, The Academy. 52 pp.