|

Online exhibits : Special exhibits : Fossils in our parklands

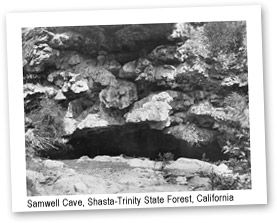

Shasta-Trinity National Forest: Samwell Cave, California

by Tony Barnosky and Pat Holroyd

Most people think of the forest and lakes of north central California as a vacation getaway, but present within this mountainous area managed by the National Park and U.S. Forest Services are some of California's oldest and youngest fossil vertebrates.

Fossils were first found in this part of California when geologists exploring the region encountered Late Triassic ammonites and ichthyosaur bones in the 1890s. These were brought to the attention of UC Berkeley's John C. Merriam, who with Annie Alexander (and various UC and Stanford faculty) made multiple expeditions there from 1901-1910, resulting in the discovery of both Late Triassic marine reptiles and Pleistocene fossils.

Working on horseback, their work to the south of Shasta Lake uncovered the nearly 220-million-year-old bones of fish-eating marine reptiles in the Hosselkus Limestone. These finds became the first evidence of the ichthyosaur Shastasaurus alexandrae (now Shastasaurus pacificus) and thallatosaur Thallatosaurus alexandrae (now Californisaurus perrini).

Samwell Cave

Samwell Cave, in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, Shasta County, is one of our most important windows into the Ice Age of California. The fossils — mostly mammals ranging in size from rodents to elephants — tell us not only what the California landscape looked like thousands of years ago, but also how ecosystems responded to a natural global warming event that happened at nearly the same time prehistoric humans were dramatically increasing in number.

UCMP involvement

The original collections from Samwell Cave were made by UC museum scientists more than a century ago. Piles of fossil bones were found at the bottom of a deep, pitch-dark pit. |

|

|

|

|

|

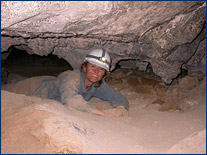

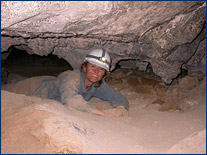

Click on each image to see an enlargement. Left: This photo, circa 1904, shows bones wrapped and ready to be hoisted out of the cave. Middle: Researcher Jessica Blois doesn't mind getting dirty in confined spaces in the name of science. Right: Several drawers full of specimens from Samwell Cave in the UCMP collections. |

Over the past five years Jessica Blois (above), now a postdoctoral scholar at University of Wisconsin-Madison, donned hard-hat, headlamp, and coveralls and excavated new sites near the cave's entrance as part of her Ph.D. research at Stanford University. The work was in collaboration with her advisor, Elizabeth Hadly, a former UCMP student and now a UCMP Research Associate and Professor of Biology at Stanford. Jenny McGuire, recent UCMP Ph.D. student and now a postdoctoral fellow at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center in Durham, North Carolina, radiocarbon-dated the bones at the Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry at Lawrence Livermore Labs. Tony Barnosky, UCMP paleontologist, and many students from UCMP and Stanford helped with the excavations.

The Samwell Cave fossils were used to reveal how mammals responded to global warming in the past, and what we might expect as we move through our current global warming episode. The big surprise is that as climate warmed at the end of the last Ice Age some 11,000 years ago, biodiversity of small mammal species decreased, and of the survivors, a "weedy" species (deer mice) became most abundant. The research was funded by the Sedimentary Geology and Paleobiology Program of the National Science Foundation (grants EAR-0545648 and EAR-0719429 to E.A. Hadly and EAR-0720387 to A.D. Barnosky).

Work on the cave faunas continues. Allison Stegner, UCMP graduate student, began a study of the blue grouse from Samwell and other Pleistocene caves while an undergraduate at Stanford. She wants to compare them with living populations in the area to see how climate change has affected their distribution and body size. This is one of the first studies of how birds respond to climate change and has significant implications for predicting future changes in bird populations as our environment continues to change.

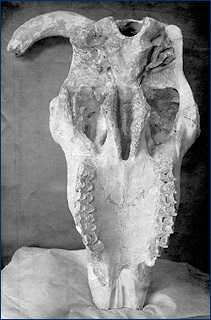

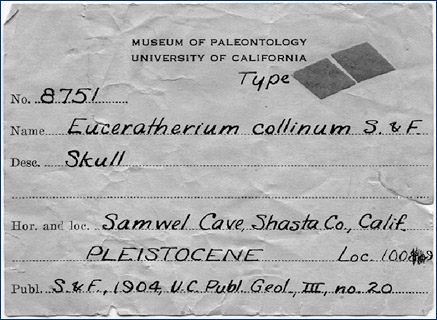

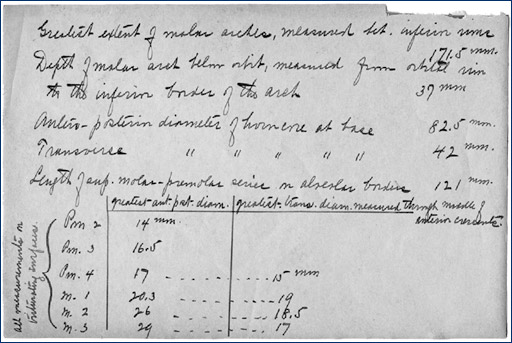

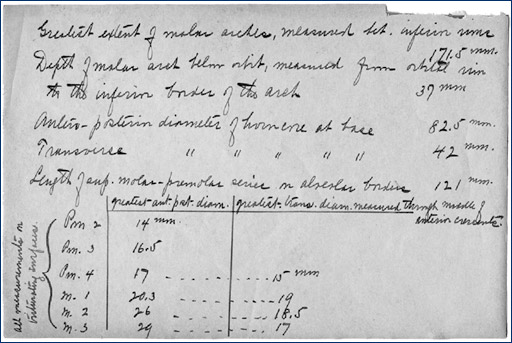

In the collections

The UCMP houses thousands of fossil bones and teeth from this site that date from just a few hundred to around 20,000 years ago. These include type specimens of musk oxen that roamed California during the Ice Age (pictured below); bones of giant California condors (below), now extinct in the area but once very abundant; and drawers full of rodent-sized bones. UCMP also archives some of the century-old notes of the first crews that brought back material from the cave (below).

|

|

|

|

|

|

Top left: A Pleistocene musk ox skull from Samwell Cave collected by Eustace Furlong around 1904. Click image to see an enlargement. Top right: The original specimen label in the UCMP collections. Bottom left: A page from notes taken by the first crews to bring back material from the cave. Bottom right: A leg bone from an extinct condor, Gymnogyps amplus, found in Samwell Cave. Click image to see an enlargement. |

|

Note: Collection of fossil material is illegal unless done under a permit from the National Park Service. If you think you have found a fossil on National Park lands, please contact a park representative.

More information

See a video of Jessica Blois and Liz Hadly excavating Samwell Cave in the summer of 2007. The video is by Gail Wight.

A May 26, 2010, UCMP blog entry

A June 16, 2010, article on Wired.com

Blois, J., J. McGuire, and E. Hadly. 2010. Small mammal diversity loss in response to late-Pleistocene climatic change. Nature 465(7299):771-774. DOI: 10.1038/nature09077

Feranec, R.S., E.A. Hadly, J.L. Blois, A.D. Barnosky, and A. Paytan. 2007. Radiocarbon dates from the Pleistocene fossil deposits of Samwell Cave, Shasta County, California, USA. Radiocarbon 49(1):117-121.

Furlong, E.L. 1906. The exploration of Samwell Cave. American Journal of Science 22:235-247.

Graham, R. 1959. Additions to the Pleistocene fauna of Samwell Cave, California. I. Canis lupus and Canis latrans. Cave Studies 10:54–67.

Hutchison, J.H. 1967. A Pleistocene vampire bat (Desmodus stocki) from Potter Creek Cave, Shasta County, California. PaleoBios 3:1-6.

McCormick, M. 1979. Species analysis of the Triassic fauna of the Hosselkus limestone, Shasta County, California. Ph.D. thesis. University of California, Berkeley.

Merriam, J.C. 1905. The Thalattosauria, a group of marine reptiles from the Triassic of California. Memoirs of the California Academy of Sciences 5(1):1-52.

Merriam, J.C. 1906. Recent cave exploration in California. American Anthropologist 8(2):221-228.

Merriam, J.C. 1908. Triassic Icthyosauria, with special reference to the American forms. University of California Memoirs vol. 1 (1).

Sinclair, W.J. 1904. The exploration of the Potter Creek Cave. University of California Publications, American Archaeology and Ethnology 2(1):1-27.

Sinclair, W.J., and E. L. Furlong. 1904. Euceratherium, a new ungluate from the Quaternary caves of California. University of California Department of Geology Bulletin 3(20):411-418.

Treganza, A.E. 1964. An ethno-archaeological examination of Samwell Cave. Cave Studies 12:1–29.