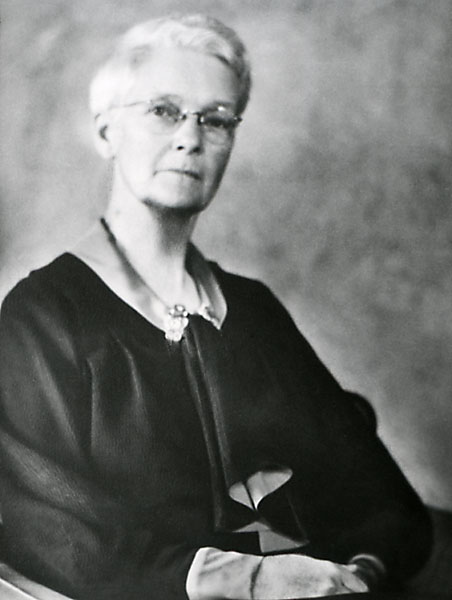

Annie Montague Alexander (1867-1950)

Benefactress of UCMP

In 1901 a young lady attending John C. Merriam’s lectures on paleontology at the University of California was so fascinated by his discoveries of extinct mammals and reptiles in northern California and Oregon that she offered to underwrite the costs of his summer collecting expedition if she could take part in the field work. Thus began the long association of Miss Annie M. Alexander with the Department and Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley (UCMP). UCMP provides access to the Papers of Annie Alexander for historians or other interested parties.

Miss Alexander’s grandparents were early missionaries from New England to Hawaii; her father successfully introduced sugar cane on Maui, and was a partner in the Matson Navigation Company. As a young lady Miss Alexander had opportunities to travel in Europe, the south Pacific, and southeast Asia. An outdoor person, she loved to camp in the mountains of California and Oregon. She took part in Dr. Merriam’s fossil collecting expeditions to Fossil Lake, Oregon in 1901, to Shasta County, California in 1902 and 1903, and to the West Humboldt Range in Nevada in 1905. This last trip, the “Saurian Expedition,” revealed a great deposit of Triassic ichthyosaur skeletons, including the largest ichthyosaurs in the world and the most complete in North America (some of these are now in UCMP’s collections). For each of these trips she paid the field expenses, and during the same period financed the collecting for the University from caves in Shasta County by E. L. Furlong and W. J. Sinclair. She endured all the hard work and hardships that can come with fieldwork. Ironically, not only did she search for and find ichthyosaur fossils, and help to pack them for the long trip back to Berkeley, but she also did much of the cooking — on an expedition that she had financed! She wrote in her account of the 1905 expedition:

We worked hard up to the last. My dear friend Miss Wemple stood by me through thick and thin. Together we sat in the dust and sun, marking and wrapping bones. No sooner were these loaded in the wagon for Davison to haul to Mill City than new piles took their places. Night after night we stood before a hot fire to stir rice, or beans, or corn, or soup, contriving the best dinners we could out of our dwindling supply of provisions. We sometimes wondered if the men thought the fire wood dropped out of the sky or whether a fairy godmother brought it to our door, for they never asked any questions…

She continued to work in the field throughout her life, celebrating her 80th birthday while on an expedition to the Sierra de la Laguna in Baja California.

In 1906 she began to make monthly contributions to support the Department’s research in paleontology; she increased her donations over the years until she established an endowment for the Museum of Paleontology in 1934. Beyond this regular contribution she made many gifts for special purposes — supporting faculty on sabbatical leave, student research visits to East Coast museums, extra funds for field expenses.

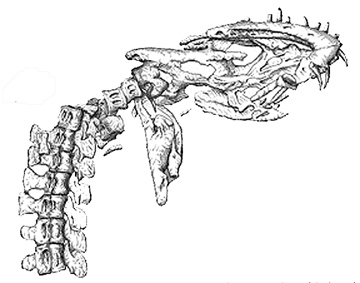

Her interests were by no means limited to paleontology. In 1907, after a hunting trip to Alaska, she proposed the establishment of a Natural History Museum at the University and offered to support its collecting and research programs. The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology was established in 1908, and when State appropriations for its construction fell far short of forecasts, she made up the difference. Her own collections of recent mammals were donated to the new MVZ. During the years that followed she and her friend Louise Kellogg collected both recent and fossil vertebrates for the University’s museums: in all, she contributed over twenty thousand specimens of animals, plants, and fossils to the University’s collections. The new species of living and fossil organisms that were named in her honor include Hydrotherosaurus alexandrae, a Cretaceous plesiosaur from Fresno County (pictured above); Swollenia alexandrae, a rare grass species from Inyo County; Shastasaurus alexandrae, a Triassic ichthyosaur; Alticamelus alexandrae, a Miocene camel from near Barstow, California; and a number of others.

Miss Alexander closely followed the field and laboratory work of the paleontologists at Berkeley. Dr. Merriam regularly wrote to her about the more important specimens collected, progress on their preparation and exhibition, and their significance for various scientific problems. She regularly visited the collections and preparation laboratory to see how work was progressing. Merriam’s successors, Matthew, Camp, and Stirton, continued this close relationship with her throughout her life.

In 1920 Professor Merriam left the University of California to become President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington. Miss Alexander was away on one of her field trips at the time; when she returned she was angry that he had not informed her of his plans. When the remaining paleontology faculty was merged with the Department of Geological Sciences (which infuriated Merriam), she arranged for the formation of a Museum of Paleontology as a separate unit of the University, independent of the geology department. Thereafter, she directed her financial support to the Museum, providing an endowment in 1934.

The reunion of paleontology and geology was not a happy one. Professors Stock and Buwalda left the University for the California Institute of Technology in 1926, and Eustace L. Furlong, curator of the paleontology collections, followed them in 1927.

Miss Alexander repeatedly complained to Presidents Barrows and Campbell concerning the need for a fireproof building for the fossil collections. She also asked them to look for an outstanding paleontologist who could re-establish a strong paleontology program. Her pleas led to the appointment of William D. Matthew, curator of fossil mammals at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, as Professor of Paleontology and Director of the Museum of Paleontology in 1928.

Dr. Matthew quickly revitalized the field at Berkeley, but unfortunately died in 1930. Again Miss Alexander put pressure on the University to provide a fireproof building for the fossil collections. In 1931 they were moved from Bacon Hall to the top floor of the Hearst Mining Building (into space vacated by the Herbarium, which had moved into the Life Sciences Building).

Miss Alexander dealt skillfully with University administrators to achieve her goals. Her offers of financial support for particular programs were carefully thought out, and always stipulated special conditions which the University must meet as its part of a bargain. These generally required negotiation. She dealt with the President, and on occasion negotiated directly with the Regents. In 1930 she approached the heads of several large corporations and banks seeking funds for the construction of a University Museum. But her timing was bad — the depression of the 1930s was underway.

She appreciated the value of scientific research. While not a research scientist herself, she had an excellent grasp of what were important questions and problems for study. She understood the necessity for proper documentation and preservation of fossils and other natural history specimens if they were to be of scientific value. An excellent judge of people, she played an important role in selection of personnel for key positions. She was intensely loyal to those she trusted. Knowledgeable in the field of finance, she is said to have chided the University Comptroller (later President), Robert G. Sproul, for not getting enough return on the University’s investments. Her own were doing much better!

REFERENCES

- Anonymous. 1980. Annie Alexander — the intrepid collector. PG&E Progress, July 1980, vol. 57, no. 7.

- The Annie Montague Alexander Papers in the archives of the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

- Personal recollections of Sam Welles.

Original text by David R. Lindberg, with additions by Ben M. Waggoner, 7/96