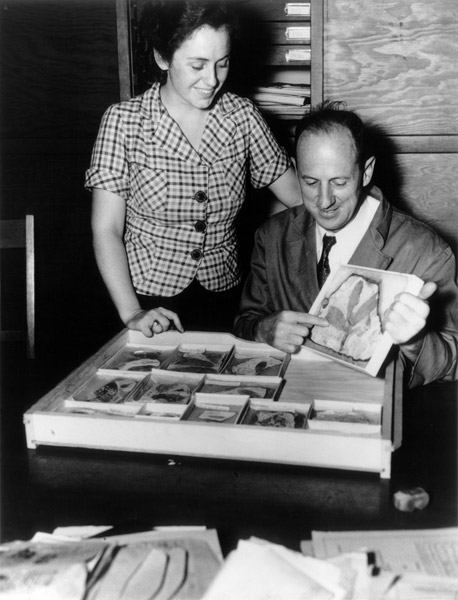

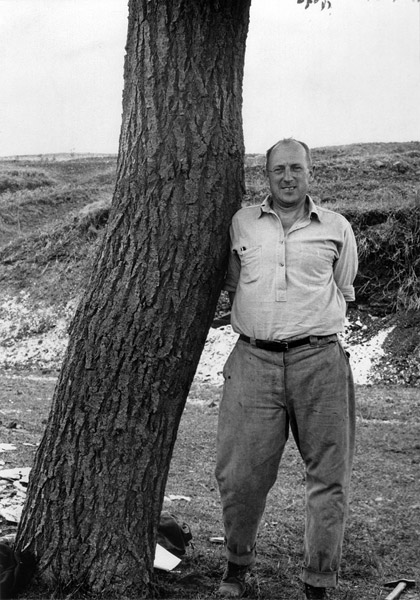

Ralph Works Chaney (1890-1971)

Paleobotanist

By UCMP student Hugh D. Hildebrant, May 1958

Between the years 1951 and 1977, a class called “History of Paleontology” was offered through the Department of Paleontology. Charles Camp taught it for the first nine years and Joseph Gregory was the instructor for the remaining years that it was offered. One of the requirements of the course was a term paper on some prominent figure or locality in paleontology. This is one of those papers. Only minor edits have been made. Original title: “Ralph Works Chaney, a biographical sketch.”

Author’s note

The biographical material contained herein was obtained principally from personal interviews with Doctor Chaney. He was kind enough to grant three afternoons and an evening of his busy schedule for this enterprise. Additional information was furnished by friends and acquaintances of Dr. and Mrs. Chaney. … Photographs are courtesy of Dr. and Mrs. Chaney and the Department of Paleontology, University of California.

Introduction

The life of a great man is very often exciting and interesting. The reasons for this are multifold. The man of achievement has gained recognition in his field for his superior capability. Generally he has an active spirit of romance and adventure — or he never would have had the will to push through the formative years of preparation and education. He must, of course, possess the mental equipment necessary to his work. But, more than that, he must enjoy his work more than anything else. For only contented individuals contribute to society. Just as others before him have learned the criteria of a good and contributory life, so too has Doctor Ralph Works Chaney.

The formative years

By virtue of background, Dr. Chaney might well have chosen a number of fields of endeavor. His ancestors on both sides of the family had been farmers — good farmers. Exactly when those people arrived in the land that was to be the United States is unknown (however, they were here early). They grew as the country grew, ultimately settling in the rich region of the Great Plains near the town of Rockford, Illinois. It was there that they prospered in modesty on the land. And it was there that the Chaney family sent down its roots to become typically midwestern.

Dr. Chaney likes to recall the family story that the Chaney name is French. He is quick, however, to add that all of the Chaneys look Irish, saying “It looks as if an Irishman wintered-over in France before coming to the United States.”

Chaney’s father left the life of active farming in order to work in wholesale woolens with Marshall Field in Chicago.

Fred A. and Laura Works Chaney had four children. Ralph was the only boy. The family home was located about ten miles from the present “Loop” in downtown Chicago on a bank of old Lake Calumet in wide-open prairie country.

Dr. Chaney was born on the 24th of August, 1890, in that section of Chicago now called Beverly Hills. He and his three sisters matured in a happy home which combined the best of city and country living.

Ralph’s first contacts were with his natural surroundings. The family raised poultry, a cow, and had a host of pets for the children. Farm life agreed with him. He began early to collect things and his interests ran the gamut from frogs to rocks.

Strewn over the surface of the ground in that area are huge boulders of granite, known to the populace in those days as “meteors.” Chaney recalls that he spent hour after hour collecting mica and feldspar crystals from these boulders to add to his precious collections. He had made his first excursion into his chosen field: the Earth sciences.

After being graduated from high school, he chose to attend the University of Chicago. As a beginning student, he planned to take a degree in zoology but he hadn’t reckoned with the type of training of the day. He immediately felt that the concentration on microscopy in the laboratory was not right — he decided it was an unreal attack on the subject, and abandoned his major for botanical training. Botany, too, was taught like zoology. There again he felt as if he were up against a brick wall of tedium. Ultimately, he took his B.S. in geology in 1912.

He augmented his training (and his pocketbook) with zoological collecting for various professors; and later, in graduate school, by accepting an appointment as a Teaching Assistant in Geology.

With his acceptance into the graduate division, Chaney found himself on the brink of an active career that has never ceased. In the spring of 1913 he took a Civil Service examination that was to have a profound effect on his work. He and several other graduate students from Chicago signed up to take the U.S. Geological Survey examination for Aide employment. The passing mark was 70% — Ralph Chaney made 69.5%. Yet, of the whole group that took the test, he was the only one to receive an appointment at the University for the following year. How had it happened? A friend in the Survey had once been a teacher at the University and had put in a good word.

That summer he was hired as a cook by the U.S. Geological Survey and spent the summer months in the Matanuska Valley of Alaska. The expedition was making a topographic survey of the region using plane table and alidade. Steamship and horseback were the only means of transportation.

Matanuska Valley is the principal temperate agricultural valley of Alaska, and it is the source of economic coal. There Chaney saw his first fossil tree.

Dr. Chaney never admits to the frequency of stomach aches among the men that summer, but he does take pride in having learned a great deal about mapping in his off hours. And that was to be of inestimable value to him in years to come.

The Survey party returned at the end of the summer. Surprisingly, Chaney does not remember the strenuous nature of the trip. Rather, he fondly recalls that it was the first time he had ever had the chance to see the ocean.

On returning to Chicago, he accepted a position with the Francis W. Parker School as teacher and coordinator of the Department of Natural Sciences. Parker School has been a training ground for numerous educators throughout the country. It was a pioneer in progressive education, and operated on the philosophy that the student should seek motivation to do for himself. Their program was called the “Activity Program.” Dr. Chaney taught biology and conducted field trips for all ages from kindergarten to seniors.

He says that he learned much about educational techniques and teaching there. But, when queried about his beliefs as to the effectiveness of progressive education, he adds, “Then, as now, such an element of choice for the student was unwise.”

The summer months of 1914 afforded him an opportunity to familiarize himself with the area of invertebrate megafossils. He received an offer to work with the Missouri Geological Survey in the Invertebrate Paleontology branch. There he became acquainted with Stuart Weller for whom he developed great admiration, and with whom he formed a lasting friendship. No work in paleobotany was done that summer. Only invertebrate fossils were treated. Dr. Chaney recalls that he definitely liked invertebrate paleontology less after that summer in the field.

Chaney has always considered himself to be a “firsthand naturalist” and he had trouble correlating his knowledge with the marine fossils he was asked to classify. Only once before had he been in proximity with the sea — the previous summer — and he had no knowledge of living shellfish ecology.

And it was at that point, perhaps, that his entire outlook changed. He had always been interested in ecology from an academic point of view. Now, however, the problem of ecology became a consuming interest. Other facets of his field were pushed more and more into the background as the new idea of interpretation of the past by environmental evaluation took hold.

In 1917 Ralph Chaney married Marguerite Seeley. She had been a history major at Chicago. He then left Parker School and accepted a post as Instructor in Geology at the University of Iowa.

Chaney was charged with teaching Principles of Geology, Historical, and Physical Geology. During the academic year 1917-1918 he developed and taught a course in military geology to Army officer candidates, the purpose of the course being to teach military mapping and basic engineering geology. That was almost his sole duty that year.

He took his Ph.D. in Geology from Chicago in 1919. In the same year he was appointed Assistant Professor of Geology at Iowa. During that year he taught his first course in paleobotany. His first paper had been published one year earlier. It concerned the now famous Eagle Creek flora of the Columbia River gorge.

Mrs. Chaney gave birth to the first of three children in 1919. He was named Richard. Ellen followed in 1922 and David in 1923.

The mature years

By 1920, Chaney had begun to produce paleobotanical papers at a furious rate. The Eagle Creek was followed up by a subsequent paper on the flora from the Puente Formation of the Monterey Group and the Rancho La Brea flora was published in abstract form a short time later.

That same year (1920), Chaney was appointed Research Associate of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, DC.

Two years before, he had been interested in moving to his already beloved West to take a position with the University of California. Although a staff appointment awaited him, his friend J.C. Merriam suggested that he wait a year or two in order to gain more experience. Moreover, conditions in the Geology Department at California were then in a state of flux. The Department of Paleontology, originally set up in 1908-1909, merged with the Geology Department in 1921. Not until 1926-1927 did it again function as an entity.

But Chaney did spend the summers of 1920 and 1921 in Berkeley while the rest of the family stayed in the Midwest. Through Merriam, funds were allocated to Chaney in 1921 by the University of California for paleobotanical work.

Shortly thereafter, Merriam left California for the Carnegie Institution, suggesting to Chaney that he too come to Washington to work with Carnegie. But Chaney did not follow Merriam. After completing his 1921-1922 teaching commitments at Iowa, the Chaneys moved to Berkeley and set up housekeeping at 1129 Keith in the Berkeley Hills where they live to this day. Chaney was given office space at Berkeley but no salary — his income continued to come from the Carnegie Institution, for which he continued to do research.

The decade of the twenties was filled with as much hullaballoo for the Chaney family as for any other, but it was of a different sort. The children were all young, and very much alive. Chaney himself, loosely associated with the Geology Department in Berkeley, turned out a prodigious amount of work. He wrote up the flora of the Payette Formation. He began extensive studies of the John Day Basin in Oregon, now recognized as the best Tertiary fossil collecting region in North America. He developed climatic theories regarding the floras of the Great Plains during the Cenozoic and was becoming interested in the “redwoods.” The Mascall and Bridge Creek floras were published in 1925.

In 1925 Roy Chapman Andrews’ Third Central Asiatic Expedition was all ready to leave the United States in order to conduct further scientific inquiry in Outer Mongolia. William Diller Matthew, long a friend of Chaney’s (Matthew was then at the American Museum of Natural History in New York but came to Berkeley two years later), recommended young Ralph Chaney to Andrews with so much zeal that Chaney was given the post of Expedition Paleobotanist.

Dr. Chaney had planned to collect some materials of his own while in Mongolia but he had little, if any, luck. Mongolia is much like our own high plains region — it is barren of Tertiary plant fossils. However, after the expedition returned to the coast, Chaney proceeded alone into Manchuria where he did collect material. He worked with the staff of the American Museum in 1925-1926.

All told, Chaney has visited the Orient nine times. The first time was in 1925; the last in 1957.

W.D. Matthew came to Berkeley in 1927 to chair the Paleontology Department but he died just a short time later in November, 1930. Chaney took over the teaching of Matthew’s Paleontology I class, and with that small beginning, Chaney launched into a teaching career at California which lasted for 27 years — a time during which the Chaney idea of ecological interpretation was instilled in a new generation of student paleobotanists.

Ralph Chaney became a full Professor of Paleontology in July of 1931. With that appointment he became Curator of Paleobotany and Museum Paleobotanist … as well as chairman of the Department of Paleontology [UCMP benefactress, Annie Alexander, was unhappy about Chaney’s appointment as chair and made quite a ruckus about it. Read about it in Part 4 of The history and development of UCMP]. It should be pointed out at this point that the Department of Paleontology and the Museum of Paleontology at California function separately.

The decade of the thirties was a time to develop into a mature teacher and thinker. With Erling Dorf, Chaney worked out the Tertiary floras of western North America. With H.L. Mason of the University’s Botany Department, he treated Pleistocene floras of North America from Santa Cruz Island north to Alaska. And in 1936 he published a paper on the succession and distribution of Cenozoic plants around the northern Pacific basin. Here at last was a handy key to following the progression of floras with the changing climates of the Tertiary. From that paper came the technique of interpreting the age of sediments by looking at the plant fossils contained therein.

The course in Paleontology 120 (Paleobotany) was also developed during those years, as was Paleontology 10, a general survey course similar in purpose to Paleontology 1. There came a steady stream of graduate students too.

Part of 1933 was spent at the famous Choukoutien Cave site in China in the search for Sinanthropus [“Peking Man,” today known as Homo erectus pekinensis]. There Chaney worked under the direction of Davidson Black, adding him to his infinite list of friends both in and out of his field. On another visit in 1937 Chaney collected the Miocene Shanwang flora for the Geological Survey of China. Father Teilhard de Chardin and Franz Weidenreich were there at the time, augmenting the pithecanthropoid search with new evidence. Dr. Chaney believes that he is still considered an honorary member of the Chinese Geological Survey but adds, “It depends on which government you are talking about.”

World War II was no surprise to Chaney — he knew it was coming and he knew there would be changes. But he didn’t realize the magnitude of those changes. On December 8, 1941, the day following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Chaney helped set up the Campus Catastrophe Relief Organization, which became the model for the Civil Defense Corps. He contributed immensely to this work.

Shortly thereafter, he volunteered to aid in the Selective Service program as Chairman of the University Area Draft Board (there were four boards in Berkeley). That was the board that took care of all students and faculty on the Berkeley campus. But then in 1943, the President of the University put Chaney in an awkward spot by giving him responsibility for conserving needed manpower for the University’s research and scientific programs. So in this role as “umpire,” he had the unpleasant task of determining who was and was not expendable. For this new role, he moved his daytime office from the Hearst Mining Building [the home of both the Department and Museum of Paleontology at that time] to the Administration Building.

Early in the war it became apparent that talented individuals might have to be reassigned to tasks outside their usual fields of expertise. Chaney had known Dr. E.O. Lawrence for a long time, and due to that acquaintance, Chaney was appointed Assistant Director of the Radiation Laboratory in 1944. At that time it was tightly bound up with the Manhattan Project, the wartime agency under whose direction the atomic bomb was developed. Chaney found himself shrouded in a cloak of secrecy during those pre-Hiroshima days.

Chaney resigned as University “umpire” at that time, but still maintained three separate offices and telephones. His new office was in the Donner Laboratory — the others in the Hearst Mining Building and at the University Draft Board felt his presence less and less. He was not teaching at the time.

Naturally the wartime effort took most of his time. Nevertheless, he continued to publish and make important contributions to paleobotany. The Dalles and the Troutdale floras were published in 1944, as was the famous paper on Eopuntia, an Eocene cactus from Utah.

After the war Chaney resumed his work with the John Day flora.

In 1948 he went to China for the last time … and returned with Metasequoia, the “dawn redwood.” Paleobotanists had long been concerned with the phyllotaxy characteristics [the arrangement of leaves on a stem] of middle Tertiary “Sequoia” — it just didn’t fit into the pattern for modern forms. Thus, when living Metasequoia was first described by a young Chinese geologist, Dr. Chaney sought out the region so that he could see these trees for himself. Chaney realized that those middle Tertiary “Sequoia” fossils that they’d been looking at were actually Metasequoia, and so the phyllotaxy problem was resolved.

That last China trip was terribly difficult. The expedition was beset with bad weather, bad food, and political difficulties. Political factors soon afterward caused the complete exclusion of Americans from the Chinese mainland. Dr. Chaney often says he wishes he might go back again, but for the moment at least, it is out of the question.

Yet Chaney has been in Japan several times since then. The last trip was in 1957. He considers Japan to be the best Tertiary plant locality in the entire world.

The personality

At present, Dr. and Mrs. Chaney have six grandchildren. Their eldest son, Dick, majored in Forestry and holds a degree in Civil Engineering. Younger son, Dave, graduated from the University of California at Davis and is a qualified wine chemist, although he now works in horticulture. Both the boys, and daughter Ellen, are married.

Other members of the Chaney family have followed an investigative career too. Dr. Chaney’s only surviving sister holds a Ph.D. in Nutrition. She is head of the Department of Nutrition at Connecticut College for Women in New London.

The Chaney sense of humor is greatly appreciated by all who know him and he is probably more in demand as a guest speaker than any other Earth scientist at the University.

He is, however, completely unforgiving when it comes to the proper care and collection of fossil plant specimens. According to Chaney, no one else knows how to wrap a field specimen. The writer recalls an afternoon during which a paleobotany class was instructed in the precise art of covering precious leaf impressions with adequate newspaper for fully half an hour.

Dr. Chaney is a member of the American Philosophical Society and the National Academy of Sciences. These honors attest to his capability. He is also a member of a host of other professional organizations including the Geological Society of America, the Botanical Society, etc. Honors have come his way from other sources as well. The University of Oregon conferred upon him an honorary D.Sc. in 1944. He is a member of Theta Tau Professional Engineering fraternity and of Gamma Alpha Graduate Scientific Society.

Within the field of conservation Chaney has devoted much time and effort. Harold Ickes appointed him to the Advisory Board of the National Park Service in 1941. From that time until 1952 he helped to plan policy for that group. Presently he is a consultant for the same branch. Chaney recalls that it was that position that gave him an opportunity to view national politics firsthand.

He has been a Director of the Save the Redwood League for some time, and an advisory member even longer. As a member of the Advisory Board for Point Lobos and various other state parks, he has contributed directly to the welfare of the people of California.

Without remuneration he has worked as a consultant on the appraisal of land sites for many state parks, and he has helped to develop more than one program of public education for California parks and National Parks.

Politically, Chaney was raised a Democrat but he has recently voted Republican. It is unusual for a scientist to feel at home in the political arena, yet Ralph Chaney is more intimate with such things than most of his colleagues. He gained a rare insight into politics while serving government in the many capacities already outlined. Chaney’s outlook on the national scene is a heartening one, for he has gained a high regard for the young professional politicians of our country — the senators and the representatives alike — who are now charged with our future. He feels that, in the majority, they are good and honest men with real talent to do the right thing. Such a philosophy is rare these days.

Speaking of his work he says, “I consider myself to be primarily a geologist. Fossils, to me, are to figure out the history of the Earth. I have very little interest in fossils as such. I am interested in pushing our knowledge of modern floras into the past … in developing the idea of plants as past vegetation. The sequence of vegetation is really not botanical, but Earth history …. Through information about distribution, plant geography, climate, and succession I try to assemble the whole picture of ecology.” Within that statement is embodied the basics of Chaney’s professional philosophy.

Two hobbies have given the Chaneys much pleasure in life. One is the collecting of oriental art. The Chaney home is a veritable display case of china, pottery, antique furniture (lacquer cabinets), and art. Of note are two great bookshelves containing numbers of volumes dealing with China and Japan.

The second hobby is Dr. Chaney’s Tertiary garden. Behind the house, on the slope of the hill, is a collection of trees and shrubs which represent over 100 million years of geologic time. There, in a neat and orderly pattern, are plants representative of, and characterizing all six epochs of, the Tertiary (with plenty from the Cretaceous too). There are ginkgos, conifers, and innumberable angiosperms (the flowering plants). One may walk in a wide semicircle from epoch to epoch, seeing how plants changed over time.

Chaney is justifiably proud of his garden. For in it is history — that romantic essence that first attracts all Earth scientists. And in it too are the miraculous green plants, the study of which he has dedicated his life.

The garden was begun after the Berkeley fire of 1923. There had been a good stand of redwoods on the hill before. Chaney had had a similar garden back in the Midwest, but there he could not raise the wealth of forms that he can grow in California. At the time of this writing the garden is in fine shape except for one thing: Chaney laments the recent loss of his prized Araucaria tree.

Uninitiated visitors might not notice the group of Metasequoia by the picnic table. They might be more impressed if they knew that more than 100,000 Metasequoia are now thriving in Japan and that over 10,000 are growing here in our own country as a result of Chaney’s 1948 trip into central China.

In 1956, Chaney was recalled to the post of Consultant with the Radiation Laboratory on the Berkeley campus and was assigned to the Director’s Office. He maintains an office there which he visits daily. He taught his last regular classes at the University in the spring of 1957.

One of his first duties with the Radiation Lab was to organize a curriculum in graduate studies in mathematics, physics, and nuclear engineering for the University of California-Atomic Energy Commission installation at Livermore, California. He spends the greater part of each day in his office at the Radiation Laboratory serving his University and his country.

When Chaney started in paleobotany, there were only three notables in the field of ecological paleobotany in the United States. Now there are many more people engaged in the field. He is reticent to offer an opinion about the quality of paleobotanical work in the earlier part of the century as compared to that a half-century later, but he does feel that palynology (the study of fossil pollen) will be the phase of the science in the immediate future.

As far as his teaching goes, he smiles a bit wryly as he tells how he happened to get into the field. He says there were two alternatives open to him at graduation: one was to work for an oil company; the other to teach. He far prefers teaching-research.

Although he is approaching 70 years of age, Ralph Chaney is not slowing down. Both he and Mrs. Chaney are as young in spirit and as vital as people half their age. And it is obvious that they both thoroughly enjoy life.

I asked Dr. Chaney what aspect of paleobotany he’d be taking on for his next research project. He said it would be the Oligocene of the Columbia Plateau, a tremendous undertaking. And after that? The answer was quick: “There’s always the Eocene,” he said.

Read a short description of Chaney’s career written by Wayne L. Fry, Daniel I. Axelrod, and Joseph T. Gregory after his death in 1971.

Ralph Chaney was interviewed in 1959 for the University of California General Library’s Regional Cultural History Project. The transcript of this excellent interview can be viewed online.