Artiodactyla: Life History & Ecology

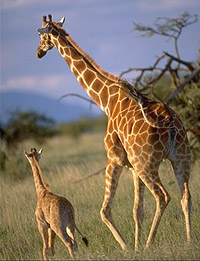

Reticulated Giraffe. Photo by Gerald and Buff Corsi, © 1999 California Academy of Sciences. |

Artiodactyls range from the rabbit-sized "mouse deer" of southeast Asia to the three-ton giant hippopotamus and ten-foot giraffes. Ecologically, they range from forest dwellers, such as wild pigs and chevrotains, to dominant large herbivores on grasslands. Artiodactyls have colonized a number of biomes characterized by extreme conditions. Camels survive in harsh deserts, while their South American kindred, the llamas and alpacas, inhabit the cold, windy peaks of the Andes Mountains. Large artiodactyls such as the caribou inhabit subarctic forests.

Hippopotamus. Photo by Gerald and Buff Corsi, © 1999 California Academy of Sciences. |

While some are solitary animals, coming together only at mating time, many artiodactyls live in extensive herds. Both solitary and herd artiodactyls use scent from skin glands to mark territories, attract mates, and/or keep a herd together.

Cape Buffalo. Photo by Gerald and Buff Corsi, © 1999 California Academy of Sciences. |

Artiodactyls often have large horns, as seen in deer, or elongated canine teeth as seen in wild pigs. These weapons are usually used in conflicts with members of the same species, often in ritualized combats between males at mating time. Such weapons may become targets of sexual selection: if females mate more with males that have large horns or antlers, large horns will be favored evolutionarily, and their average size will increase over time within a species. This is thought to explain the enormous antlers in species such as the Irish elk. Some armed artiodactyls can and do use their horns as defenses against predators — the Cape buffalo is said to be more dangerous than a full-grown lion — but many rely on speed to outrun would-be predators, and on their keen senses of sight, smell and hearing to detect predators.