Home | Session 3 | Sedimentary Rock Pg 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

What's in a Sedimentary Rock?

Presented

by Carol Tang

California Academy of Sciences

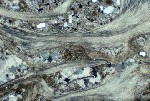

This next set of slides use one fossil occurrence--an oyster boundstone from the Jurassic Carmel Formation of southern Utah--to show how one can use evidence from different spatial scales to learn something about biology, ecology, and geology.

updated February 11, 2002

UCMP Home | What's new | About UCMP | History of Life | Collections | Subway