Crustaceamorpha: Parasitism

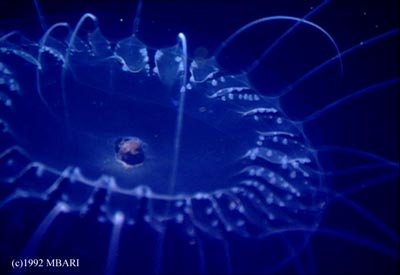

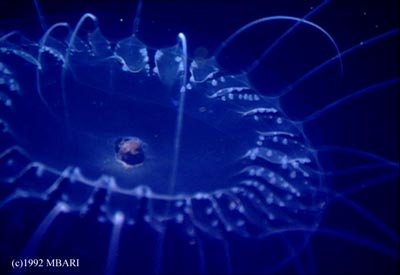

Parasitic amphipod on the jelly, Solmissus. Image used with permission from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. |

Parasitic amphipod on the jelly, Solmissus. Image used with permission from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. |

Some parasites look for very specific hosts to attach to, sometimes attaching only to a single host species; these are called obligate parasites. Other parasites will feed on any host available and are called facultative parasites. Obligate parasites are generally considered more evolved because of the adaptations they possess that require them to feed only on certain organisms. Often through time a host species can adapt defenses to the parasitic species. The parasite must then adapt to the new defenses or find a new host species. This cycle of adaptions is called coevolution, which leads to the specific host/parasite relationship of obligate parasites. Some of the adaptations of parasites are astounding. Because of the adaptations associated with a parasitic lifestyle, many parasitic crustaceans are practically or completely unrecognizable as a member of the taxa they are most closely related to except during early larval stages.

Here's an example of two crustacean taxa—one parasite and one host—and the adaptations they possess for parasitic life. Rhizocephala belong to the group Cirripedia (barnacles) and are endoparasites on decapods (shrimps and crabs). Rhizocephala are unrecognizable as members of the Cirripedia group—in fact, it is difficult to recognize them as a separate animal from their decapod hosts. As adults they lack appendages, segmentation, and all internal organs except gonads and the remains of the nervous system. Other than the minute naupliar stages, the only distinguishable portion of a rhizocephalan body is the externa or reproductive portion. A female nauplii settles on a host and metamorphoses as it penetrates the internal portion of the animal. It then ramifies, or grows in a similar manner as a root system, through the host centering on the digestive system. Once mature, the female produces a sac-like externa on the abdomen of the host. The externa is immature until a male nauplii settles on it and fuses with it. The externa then produces two types of eggs, small ones that will become female and large ones that become males. Because the externa is located in the same location as the host's egg sac would be, the host is fooled into thinking that the parasitic externa is its own egg sac. It cares for the rhizocephalan externa as if it were its own egg sac and never molts again (crustaceans don't molt until they release their eggs or young from the brood pouch). The host is so well fooled by the externa that even male hosts, which would never have carried eggs or young in a brood pouch, care for the externa as if they were females.

This table shows the crustacean groups that contain parasitic species.

| Group | Example | Endo/Ectoparasite | Hosts | Relative # |

| Branchiopoda | Cladocera | Ectoparasites | Hydra (related to portugese man | few |

| Maxillopoda | Copepoda | Both | other invertebrates and fish | many (more than 7 higher taxa) |

| Maxillopoda | Branchiura | Ectoparasites | fish | all |

| Maxillopoda, Cirripedia | Rhizocephala | Endoparasites | crabs and shrimp | all |

| Maxillopoda, Cirripedia | Ascothoracians | Ectoparasites | echinoderms and anthozoans | all |

| Maxillopoda | Tantulocarida | Ectoparasites | deep-sea crustaceans | all |

| Malacostraca | Isopoda | Both | jellyfish, fish | few |

| Malacostraca | Amphipoda | Both | jellyfish, fish | few |