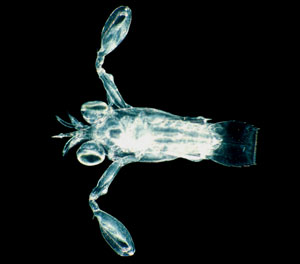

Stomatopod larva. Image provided by Roy Caldwell, UC Berkeley. |

Adult crustaceans are extremely morphologically diverse. When larval morphology is considered, the range of shapes, sizes, and bizarre morphological features multiplies many times. This wide range of morphological diversity makes is difficult to generalize about larval forms and the stages they pass through as they grow, but we will try.

Two strategies are followed by various groups of crustaceans. A group is either "direct developers" that emerge from the egg fully formed and only increase in size as they mature, or they exhibit anamorphic growth. In anamorphic growth the morphology of the individual that emerges from the egg changes with each molt. Usually the changes involve adding segments and appendages as well as increasing in overall size. Some animals show much more dramatic changes as they metamorphose, like those seen in the stomatopod shown at left. In anamorphic growth, the larvae often look nothing like the adult.

The differences between the appearance of larval and adult stages led to much confusion in the past when larval forms were often named as completely different species or even assigned to different higher taxa than the adults. Much of this confusion has been cleared up by researchers who raise animals from the egg to adulthood, and thus can document the changes in morphology of a single animal. This is often very difficult because each stage in the life cycle may require different conditions and each small change that the researcher makes to the environmental conditions can induce unnatural changes in the developing larvae. For this reason, much remains to be learned about the growth and development of many crustacean groups.

Part of the larval period of most crustaceans is spent in the plankton (swimming or floating up in the water). While living in the plankton, they either feed on planktonic algae or animals, or they live off of yolk retained from the egg. Larvae spend varying amounts of time in the plankton, from minutes to over a year. The difference in time spent there heavily impacts how far from the parents the larvae are spread. The longer a larva spends in the plankton, the further it is able to disperse from where its parents were. Whether dispersal away from the parents is favorable or unfavorable depends on the ecology of the species. For example, animals that live on seamounts (submerged mountains that rise from the sea floor at least one thousand meters) often have very short planktonic periods because if they are washed away from the seamount, it is unlikely they will find another seamount to settle on. On the other hand, it can be important to disperse far from your parents to ensure the continual mixing of genes within a species. The question of dispersal during larval stages and its impact on where and when a species is found is a very active research area. Being able to predict where and when larvae of any group are going to be present is especially important to fisheries managers, because crustacean larvae are an important food source for many fish. No food means no fish!

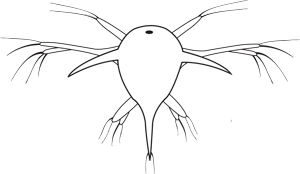

Generalized naupli. Image used with permission from Karen Osborn, UC Berkeley. |

There are three basic types of larvae found in crustacean groups. The larvae are seperated into groups and named by the appendages they use for swimming. Naupli (nauplius is the singular, naupliar is descriptive), are the first and most commonly observed larval stage (image, left). Producing naupliar larvae is a characteristic often used to identify crustaceans, however there are a few groups that do not produce naupliar larvae. A good example is members of the Isopoda, which produce fully formed young. A nauplius consists of the first three cephalic segments and the appendages belonging to those segments, the antennules, antennae, and mandibles. Naupli have a single eye in the middle of the anterior portion of their body. This eye is sometimes retained in the adults and it referred to as a naupliar eye. Naupli have a cephalic shield or the beginnings of the dorsal carapace, and no segmentation on the trunk. Naupli swim using the antennules and antennae. As the naupli go through successive molts they add segments and appendages.

The other two types of larvae, Zoea and Megalopae, are only found in members of Malacostraca. The carapace of a zoea covers the head and the forward portion of the thorax. Zoea have compound eyes, thoracic segments with the appendages belonging to the segments, as well as some abdominal segments. Zoea use their thoracic appendages to swim. Megalopae are sometimes called post larvae and are intermediate between the planktonic and benthic (associated with the sea floor) periods of their life cycle. This is the stage that chooses where it will settle and metamorphoses into the adult. Megalopae swim using their abdominal appendages or pleopods.

| Larval Stage | Appendages used to swim | Segments and Appendages Present |

| Naupli | cephalic (antennules and antennae) | First 3 cephalic, posterior portion when present unsegmented |

| Zoea | thoracic | cephalic and thoracic, later with abdominal |

| Megalopae | abdominal |

cephalic, thoracic, and abdominal |