|

Online exhibits : Special exhibits : Fossils in our parklands

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park, Nevada

by Dave Smith

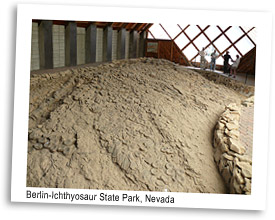

Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park is located near the mouth of West Union Canyon in the Shoshone Mountains of central Nevada. Berlin, a ghost mining town, is on the National Register of Historic Places. The ichthyosaur site, a National Natural Landmark, is about two miles from the town. There, a building protects an exposed bedrock surface that contains the bones of several giant ichthyosaurs. These marine reptiles died and were buried in sediments about 217 million years ago during the Triassic period (upper Carnian). At that time, an arm of what is now the Pacific Ocean covered portions of the west, including present-day Nevada. The ichthyosaur-bearing rocks, which also contain ammonites, are part of the Luning Formation.

Ammonites and marine bivalves were probably the first fossils to be found here, but it is believed that early miners were the first to notice the ichthyosaur bones. Apparently, the miners used some in building their fire hearths. The first person to recognize the bones as belonging to giant ichthyosaurs was Siemon W. Muller of Stanford University in 1928. Twenty-four years later, in 1952, Mrs. Margaret Wheat of Fallon collected some of the ichthyosaur bones and brought them to the attention of UCMP's Charles Camp. Mrs. Wheat brought Camp out to the site a year later. |

|

|

|

|

|

Click on any of these images to see enlargements. Left: The Visitor's Quarry building protects the ichthyosaur bonebed from the elements and vandals. Note the ichthyosaur relief at the far right. Middle: The exposed bonebed surface. The bone and matrix are the same color so it is difficult to identify the bones in this photo. Right: A portion of the 60-foot-long relief of Shonisaurus by William Huff, sculptor and long-time friend of Charles Camp. |

UCMP involvement

After his first day at the site, Camp wrote in his field notes:

Si Muller says he found these ichthyosaur remains in 1929 and 30 and tried to sell the idea to us then and subsequently — Mrs. Wheat told me about them last September and said that the vertebrae were very large (up to 1 ft. in dia.) and 21 pounds weight ….

We went up the south facing slope … and looked over the material exposed by Mrs. Wheat's broom …. It is a series of six or more vertebrae in hard limestone, and much more float below. These are monster vertebrae — larger than any ichthyosaur vertebrae hitherto known and later in age then the Middle Triassic Cymbospondylus (Leidy).

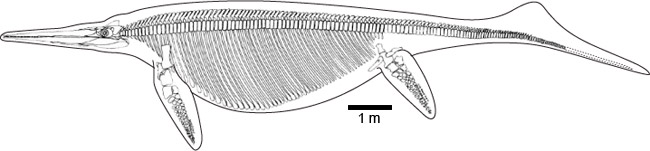

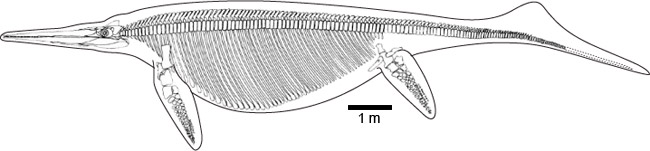

Camp was right about the ichthyosaurs being the largest yet known — some reached lengths of more than 15 meters (49 feet). These ichthyosaurs, named Shonisaurus popularis by Camp, remained the size champs until 2004 when Nicholls and Manabe (see reference below) described another species of Shonisaurus from British Columbia that measured 21 meters in length.

Camp believed that the unusual concentration of skeletons — he discovered nearly 40 individuals — was due to the creatures being stranded during unusually low tides, but later studies of the sedimentology by UCMP grad student Jennifer Hogler indicated a deep-water depositional environment. So the reason for this odd concentration of ichthyosaur skeletons — the greatest concentration of ichthyosaur skeletons known — remains something of a mystery.

Top: Charles Camp believed that the concentration of skeletons was due to the ichthyosaurs being stranded at low tide. William Huff depicted the scene in this drawing. Click the image to see the entire drawing. Bottom: A reconstruction of Shonisaurus popularis based on Kosch 1990, McGowan and Motani 1999 (see both references below), and personal communication with R. Motani (November 2010). |

It took only a few days for Camp to realize the importance of the ichthyosaur site and he and Margaret Wheat began a drive to turn it into a state park. He wrote:

This is a thing that should be preserved in situ for all to see. It will probably not be duplicated again in this world. Peg Wheat is working now with Fleishman [sic] Foundation [the Max C. Fleischmann Foundation which did provide funds for the work] and Governor to get funds to preserve. I must write to Kerr [UC Berkeley Chancellor Clark Kerr] to get O.K. from UC.

Camp and Wheat made a formidable team, for in less than two years the Nevada Legislature had established the Ichthyosaur Paleontological State Monument, and in 1957 the site was incorporated into the State Park System. As icing on the cake, the Legislature designated Shonisaurus popularis the state fossil of Nevada in 1977.

|

|

|

|

|

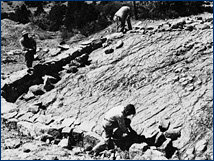

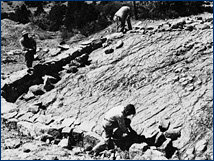

Click on any of these images to see enlargements. Left: A visitor to the quarry points to an ichthyosaur femur. A series of disc-shaped vertebrae are just to the left of the femur. Middle: Charles Camp studies the bonebed surface in the summer of 1955. Right: Workers construct a low wall around the exposed bonebed in 1955. |

Extensive excavation of the ichthyosaur skeletons was carried out by groups of students under the direction of Camp and Sam Welles — with the assistance of numerous friends, family members and visitors — in the summers of 1954 to 1957. Camp did additional work at the site between 1963 and 1965. Camp removed only four partial ichthyosaur specimens for study — the rest were left in place, many being reburied to protect them. Sam Welles returned to Berlin-Ichthyosaur in 1984 with a group of University Research Expedition Program (UREP) volunteers on a mission to do further preservation and mapping of the exposed skeletons.

In the collections

UCMP actually has very few fossils from Berlin-Ichthyosaur — there are only a handfull collected during Camp's first exploratory look at the site in October of 1953. The partial skeletons that he excavated were originally stored at the Marjorie Barrick Museum, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, but in 1999 they were transferred to the Nevada State Museum, Las Vegas.

|

|

|

Click on these images to see enlargements. Left: A Shonisaurus vertebra collected by Margaret Wheat that resides in UCMP's invertebrate type room. Why is it with the invertebrates? Right: Because of the presence of this fossil, found on the vertebra's surface. It has been described (see the Hogler and Hangar 1989 reference below) as a chondrophore, a hydrozoan similar to today's By-the-wind Sailor (Velella). |

Note: Collection of fossil material is illegal unless done under a permit from the Nevada Division of State Parks. If you think you have found a fossil on state park lands, please contact a park representative.

More information

See the Nevada Division of State Parks page on Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park.

Find a wealth of Shonisaurus popularis information, art and photos on the Oceans of Kansas website.

Camp, C.L. 1976. Vorläufige Mitteilung über grosse Ichthyosaurier aus der oberen Triassic von Nevada. Sitzungsberichten der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenshaftliche Klasse, Abteilung I 185:125-134.

Camp, C.L. 1980. Large ichthyosaurs from the Upper Triassic of Nevada. Paleontographica, Abteilung A 170:139-200.

Camp, C.L. 1981. Child of the rocks — the story of the Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Special Publication 5. 36 pp.

Hogler, J.A. 1990. Community replacement in the Upper Triassic Luning Formation, Shoshone Mountains, Nevada. Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs 22(3):29.

Hogler, J.A., and R.A. Hangar. 1989. A new chondrophorine (Hydrozoa, Velellidae) from the Upper Triassic of Nevada. Journal of Paleontology 63(2):249-251.

Hogler, J.A. 1992. Taphonomy and paleoecology of Shonisaurus popularis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria). Palaios 7(1):108-117.

Kosch, B.F. 1990. A revision of the skeletal reconstruction of Shonisaurus popularis (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 10:512-514.

McGowan, C., and R. Motani. 1999. A reinterpretation of the Upper Triassic ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 19:42-49.

Montague-Judd, D.D. 1999. Paleo-upwelling and the distribution of Mesozoic marine reptiles. Ph.D. thesis, University of Arizona. 456 pp.

Nicholls, E.L., and M. Manabe. 2004. Giant ichthyosaurs of the Triassic — a new species of Shonisaurus from the Pardonet Formation (Norian: Late Triassic) of British Columbia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 24(4):838-849.

Silberling, N.J. 1959. Pre-Tertiary stratigraphy and Upper Triassic paleontology of the Union District, Shoshone Mountains, Nevada. Geological Survey Professional Paper 322:1-67.