The Eusuchia

Extant crocodiles and their close relatives

The clade Eusuchia (literally, "true crocodiles") includes extant crocodilians and their closest relatives. The clade first appeared in the Cretaceous Period and most extinct eusuchians did not differ much from their living descendants.

Living crocodilians are divided into three groups based on their morphology (body form), habits, and diet. The clade Alligatoridae includes two species of alligators and five species of caimans, all from the Americas except for the Chinese Alligator. Crocodylidae is distributed worldwide in the tropics and includes 13 or 14 species of true crocodiles, depending on how they are classified. Gavialidae includes one or two species (see below) of slender-snouted gharials, both of which are found only in southern and southeast Asia.

The three groups — alligators and caimans, true crocodiles, and gharials — are most easily identified by the shapes of their heads. Alligators and caimans have short, broad, U-shaped snouts; gharials have very long, narrow jaws, almost like forceps; and true crocodiles are intermediate between the other two, with fairly long, V-shaped snouts. These jaw shapes are related to differences in diet. Although they willl also eat many other animals if given the chance, gharials are specialized fish-eaters, and use their long, narrow snouts and thin, sharply-pointed teeth to catch their fast and slippery prey. Gharials live mainly in large river systems and spend less time on land than other crocodilians. True crocodiles eat fish, shellfish, other reptiles, birds, and mammals, with much variation in diet among individuals, populations, and species. Alligators and caimans have a similarly varied diet. Oddly enough, both alligators and caimans have also been observed eating fruit on occasion — hardly what one expects for giant predators. Maybe this dietary flexibility shouldn't be surprising, given the existence of short-snouted, herbivorous crocs and croc relatives in the fossil record. Baby crocs eat mostly insects and crustaceans until they are large enough to take bigger prey. Like mammals and birds, crocodilians have a complete secondary palate, a slab of bone that separates the nasal passages from the mouth. This allows crocs to breathe with their mouths full.

|

|

|

|

|

|

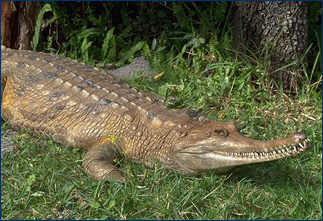

Clockwise from top left: The False Gharial, Tomistoma schlegelii; American Crocodile, Crocodylus acutus; Indian Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus; and American Alligator, Alligator mississippiensis. |

||

The nostrils, eyes, and ears of crocodilians are mounted high on the head. This allows a croc to float in the water with as little of its body exposed as possible. Such camouflage is important to keep small crocs safe from terrestrial or aerial predators, and to help bigger animals ambush prey. Crocodilians ambush land animals when they come to rivers or water holes to drink. A well-camouflaged croc will suddenly lunge forward and catch the unsuspecting prey by the head or neck. It will then drag the animal into the water and kill it by drowning or dismembering it. An attacking crocodile will often perform a "death roll," in which it holds the prey firmly in its jaws and rolls over and over in the water. This may disorient the prey and hasten its death by drowning, but it often leads to dismemberment as well; the part of the prey that is caught in the croc's jaws is frequently ripped away from the rest of the carcass.

Most crocodilians swallow rocks and carry them in their stomachs for long periods of time. The function of these gastroliths (literally, "stomach stones") is unclear. They are usually assumed to function as ballast, to help crocodiles control their buoyancy. However, recent research shows that the total mass of gastroliths carried by one animal is usually only one or two percent of the body mass, and that the impact of gastroliths on buoyancy is minimal (Henderson, 2003).

Extant crocodiles frequently enter salt water and are capable of surviving ocean journeys of hundreds of miles. Crocodiles are often found along chains of oceanic islands, sometimes very far from the mainland. Examples include the American Crocodile in the West Indies, the African Crocodile on Madagascar, and the Saltwater Crocodile in the Malay Archipelago. Crocodiles have special salt-excreting glands on their tongues that help them rid their bodies of excess salt from seawater. Extant gharials, alligators, and caimans lack these glands, and not surprisingly they differ from crocodiles in preferring fresh water to salt water. However, the fossil history of both alligatorids and gavialids includes examples of trans-oceanic dispersal. It is possible that extinct alligators and gharials had salt glands, which have been lost in the extant species.

Probably the most controversial living crocodilian is the False Gharial, Tomistoma, a slender-snouted form from Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo. In phylogenetic analyses based on morphological characters, it is usually recovered within Crocodylidae, which would mean that its similarities to gharials represent convergent evolution. However, molecular data suggests that Tomistoma and the "true" Indian Gharial, Gavialis gangeticus, are each others' closest relatives. If that is the case, then the similarities between the "true" and "false" gharials are homologies inherited from a common ancestor, and it is the similarities between Tomistoma and crocodiles that are convergent.

The fossil record

Extant crocodilians are frequently described as "prehistoric-looking," as if they are relicts of the Age of Dinosaurs. And in fact there is some truth to this perception. The fossil record of alligatorids and crocodylids extends back into the Cretaceous Period. The earliest known gavialids are somewhat younger, from the Eocene Epoch of the Cenozoic Era, or Age of Mammals. However, because their sister group was present in the Cretaceous, gavialids must be at least that old; we simply haven't found fossils of their earliest representatives yet.

The fossil record of crocodilians includes many gigantic extinct forms, including:

All of these animals had skulls between 1.3 and 1.5 meters (4-5 feet) long and estimated body lengths of 10-12 meters (33-40 feet) or perhaps even larger. The largest known skull of Sarcosuchus is 1.78 meters long (5 feet, 10 inches), but it was very long-snouted and the largest individuals of Deinosuchus may have been longer overall. None of them are known from complete material, so determining which one was the biggest is difficult or impossible.

The concentration of giant crocs in the Miocene of South America is especially remarkable. The alligator Mourasuchus, caiman Purussaurus, and gharial Gryposuchus all lived alongside one another. They must have specialized in different environments or types of prey to have coexisted successfully at such large sizes.

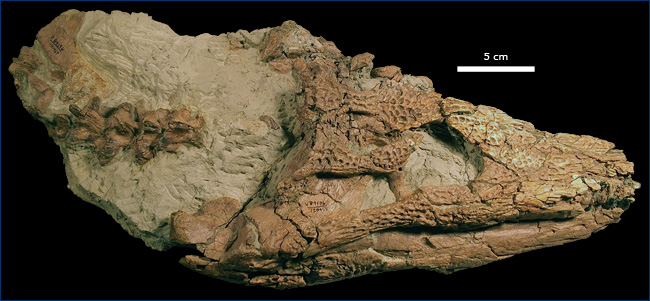

The skull, mandible, and ventral osteoderms of Borealsuchus sternbergii (specimen no. 130469), collected from the Paleocene Tullock Formation, McCone County, MT, by UCMP's J. Howard Hutchison, 1984. |

Despite the variation in skull shape and diet among alligatorids, crocodylids, and gavialids, extant crocodilians represent only a small fraction of the diversity of their extinct relatives. At various times in their long history, crocs have evolved into tiny insect-eaters, long-legged terrestrial runners, and pug-nosed, armored herbivores. Living crocodilians are the last representatives of a great flowering of archosaurs that rivaled dinosaurs and birds in its diversity of sizes and forms, and fascinating and valuable animals in their own right.

Sources

|

||

Text by Matt Wedel, 5/2010; photos of False Gharial, American Crocodile, Indian Gharial, and American Alligator by Gerald and Buff Corsi © 2001 California Academy of Sciences; Borealosuchus photo by Dave Smith, UCMP