Online exhibits : Special exhibits : Fossil footprints

Fossil footprints through geologic time

I. How tracks are preserved

By Allison Vitkus, Karen Chin, and Martin Lockley

Tracks are made when an animal makes an impression in soft sediment like sand or mud, leaving an imprint in the ground. We have all observed animal tracks or trails in modern environments. But how can such tracks be preserved for millions of years?

The vast majority of tracks are not fossilized — they are destroyed shortly after they are made. Tracks can be obliterated by being eroded by water, blown apart by wind, stepped on by animals, or damaged by other forces. It might seem like burying tracks would destroy them, but a blanket of sediment actually helps protect footprints. Another way in which a track can be protected is when an animal's foot sinks deeply into the sediment, creating a footprint below the surface, where it cannot be eroded. If buried tracks are later re-exposed, they will be more easily recognized if the sediment that buried or filled them has different characteristics than the sediment in which the tracks were originally made. One example of this is when footprints are made in fine-grained mud and are then covered with a bed of sand. However, tracks covered by similar sediments may also be distinguishable if the track surfaces are slightly altered before burial, resulting in a clear division between the tracks and the sediment that covers them. The bottom line is that burial under the right conditions helps protect footprints.

It is important to remember that footprints are fossilized under special conditions. Because most tracks are made in wet sediment, they are often preserved near bodies of water or in areas with shallow water, such as lakebeds. This means that fewer animal tracks are preserved in habitats that are not near bodies of water. However, tracks can also be preserved when animals walk on sand dunes moistened by dew.

Different modes of track preservation

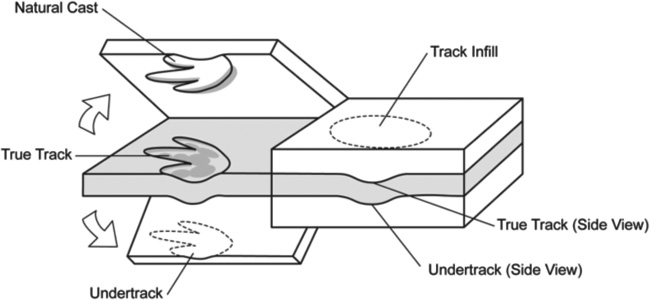

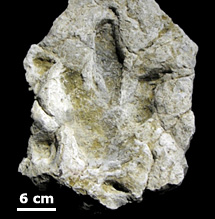

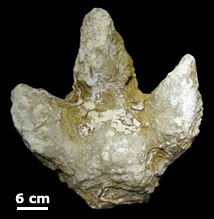

Fossil footprints do not always represent the original animal track; multiple types of fossil tracks can be made from a single step. The fossil of the actual footprint, the indentation that is left behind when an animal steps in soft sediment, is called a true track. Sometimes details like skin impressions are preserved in true tracks. The layers of sediment beneath the actual track layer that the animal stepped on are also affected. The dent in these sediments caused by the pressure of the animal's weight is called an undertrack. Undertracks have less detail preserved than true tracks.

Sediment that fills an original footprint (true track) and becomes lithified (hardened in stone) represents a natural cast of the track. Natural casts are like three-dimensional replicas of an animal's foot. As such, they can preserve informative foot details (such as skin impressions) just like true tracks. Sometimes depressions in the layer of sediments deposited above tracks can also be filled. These are called track infills. Like undertracks, track infills have less morphological detail. However, in some cases track infills can be used to find fossil footprints which have not been completely exposed by erosion — and help paleontologists find true tracks.

References

Lockley, M.G., and A.P. Hunt. 1995. Dinosaur Tracks and Other Fossil Footprints of the Western United States. Columbia University Press, New York. 338 pp.

Lockley, M.G., and C.A. Meyer. 2000. Dinosaur Tracks and Other Fossil Footprints of Europe. Columbia University Press, New York. 360 pp.

NASA Images. http://www.nasa.gov. Accessed March 5, 2013.

Tucker, M.E. 2001. Sedimentary Petrology: An Introduction to the Origin of Sedimentary Rocks, 3rd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. Hoboken, New Jersey.

1UCM refers to the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History. The collection was originally built by the University of Colorado Denver, and was displayed at the Dinosaur Tracks Museum on the Denver campus. The fossil tracks are now housed at the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History in Boulder, Colorado, and the images of these specimens are courtesy of the University of Colorado.