Researching whelks in Japan: Field notes from Jann Vendetti

By UCMP grad student Jann Vendetti, July 6–9, 2008

| Sponsored by the NSF (National Science Foundation) and the JSPS (Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science), Jann is studying fossil and living whelks — a type of snail — in Japan, the home of more than one third of all extant whelks. Jann is interested in the evolution and dispersal of whelks through time and in their different modes of developmental growth. For more photos and more details of Jann's adventures in Japan, visit her blog. |

July 6, 2008

From Rikuzen-Takata in Iwate Prefecture, I made the short trip to the city of Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture. Visiting Sendai was a top priority for four reasons: (1) it was hosting a meeting of the Paleontological Society of Japan that I wanted to attend; (2) a private shell collector in Sendai invited me and my Japanese host to look at his whelk collection; (3) the Sendai fish market would be a good place to search for whelk species, particularly ones living off northern Honshu and Hokkaido; and (4) Tohoku University in Sendai has a natural history museum with whelk holotype and paratype specimens that I wanted to examine.

Tonight I am staying in a Japanese business hotel, which means that my room is about the size of a large closet with a bathroom and a television. Breakfast this morning was sweet red bean bread and iced coffee from the nearby Lawson Station (a convenience store like 7-11, which they also have here) and dinner was a popular rice and green tea soup called ochazuke.

After checking into the hotel, I spent most of the afternoon exploring the city. This hotel was within walking distance of some famous Sendai sites, so I was excited to get to see a lot in a short time. My first stop was the site of the former Sendai Castle (Sendaijo). Only ruins of the castle remain after it and the whole city were bombed heavily during WWII. The original castle was built in 1602 by Date Masamune, one of Miyagi Prefecture's most famous leaders. His imposing statue stands where the castle would have been. Date Masumune's influence and importance in Sendai are reflected in the extensive grounds of his family's mausoleum, called Zuihoden, and in the size and intricate decoration of the tombs.

July 7, 2008

Today I attended day one of the Paleontological Society of Japan meeting. Between poster sessions, lunch, and numerous talks, there were three things that made an impression on me. First, upon arrival I picked up the book of talk abstracts, then went to make myself a name tag. The name tag was not the pin-on variety that I was familiar with, but an upside-down L-shaped card. There was a wider portion with a line for my name, but I could not figure out how to attach the card to myself and wondered what the "tail," the long part of the upside-down L, was for. When I looked around at the other meeting attendees, it all became clear. The "tail" slides into one's business shirt breast pocket, with the name tag part sticking out above. Since the meeting's attendees were predominantly male and they all wore the same "uniform" of slacks and short-sleeved shirt with a pocket, the name tags were perfect … for them. I removed the "tail" from mine and attached my name tag to a pin-on backing that the organizers found for me.

The second thing that left an impression on me was the behavior of the audience following a talk — there was no clapping like there is at such meetings in the U.S. When a presenter finished speaking, there would be a moment or two of silence, then questions would be asked. Perhaps this cultural difference was so obvious to me because almost all of the talks were in Japanese. Since I understand very little Japanese, my attention was more focused on other details, such as slide organization, body language, and audience reactions.

And lastly, all the molluscan paleontologists to whom I was introduced by my host Dr. Hayashi, were friendly, warm, and welcoming. This was especially comforting as I was one of the only foreign attendees.

Later in the afternoon I got a chance to look through the collections of Tohoku University's Museum of Natural History. Tohoku is the largest university in Sendai and was hosting the paleontological meeting that I was attending. In the Museum's paleontological collections I found Oligocene and Miocene whelk specimens and examined them for intact protoconchs.

July 8, 2008

Today, following the paleontology meeting sessions, my host and I were picked up by Mr. Higuchi, a Sendai resident of 30+ years and an avid molluscan shell collector. I didn't realize just how avid, until we reached his second "home." Mr. Higuchi didn't live here. Instead, he used the entire house to store part of his shell collection! This man is serious. Between his limited English and my limited Japanese we "discussed" whelks using the Latin genus and species names, which were familiar to both of us. He then took us to his other home, the one in which he lived, but where he also kept an extensive shell collection stored in a climate-controlled room. It was getting late and we had limited time, so I asked him if he could show me the rare whelk specimens that he had. He was happy to do so … and what a gold mine!

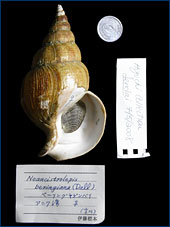

Some of Mr. Higuchi's most spectacular and rare specimens are whelks that coil the "wrong way" — that is, to the left. Most marine snails coil to the right (dextral coiling), so that when you hold a shell with the aperture (the opening where the animal would emerge) facing you, the aperture is on the right side of the shell. However, if a snail of a dextral-coiling species carries certain mutations, it might coil to the left instead. On the other hand, some species are normally left-handed coilers (sinistral coiling). Because the shell reflects the development of the snail from larva to adult, this left-handed coiling must begin early in its life — as soon as the snail starts depositing its adult shell. Since so few marine snails are sinistral coiling, you might wonder whether there is something inherently disadvantageous about it. This doesn't appear to be the case. It takes years for a whelk to grow to its full adult size, so we know that large sinistral whelks must do just fine despite their opposite coiling. Below (bottom left image) you can see examples of both dextral and sinistral individuals in the genus Neoberingion. Dextral coiling is normal for this species, so we know that its sinistral partner has a mutation for left-handed coiling. The three images at the bottom right are some other examples of sinistral whelk individuals of otherwise dextral species.

|

|

|

||

July 9, 2008

This afternoon I am heading back to Nagoya via the Shinkansen (bullet train), but not before checking out the Sendai fish market for whelks. Whelks are a relatively popular seafood in Japan and are eaten as sashimi (raw) or sometimes simmered in a broth. The Sendai fish market was outside, open early, and to my delight, full of tsubu-gai (Japanese for "whelk"). The diversity of seafood astonished me and included familiar marine animals like fish and squid, but there were also ones that I did not expect to see, such as sea squirts (ascidians) and barnacles. Amazing! I am excited to go back to Nagoya to explore its fish market and see what other species I can find.

Jann remained in Japan for another month and a half or so — you can read about her further adventures there and see lots of photos on her blog — but she is almost done evaluating her data and her dissertation is nearing completion. Read a summary of her Japan-based research in her final installment!

All photos by Jann Vendetti.