|

|

|

|

Left: On the road outside Addis Ababa, Mark, Randy, and Greg head north toward the Blue Nile Gorge. Mark rides in the front car with Chalachew. They're hard to see in this picture but spare tires and extra fuel are strapped onto the roof rack. Pedestrians line the highway in both directions. Center and Right: Views from the car window. Eucalyptus trees are everywhere — they provide much of the firewood, structural lattice for scaffolding, walls, roof trusses, etc. |

We stop in Mukaturi for lunch at a "hotel" — these tend to be low, single-story, colorful, cinder block buildings with a series of rooms, each measuring about 8 x 10 feet. But we're here for traditional Ethiopian food — roast lamb, or "tibs"— and it's very good. Chalachew orders "chocolate" tibs — well, it's actually called shekla tibs, but it sounds like "chocolate tibs" to us. Served on top of a sizzling little oven, the meat is crispy and flavorful, with grilled onions and peppers. Teshome and Abdi eat with us, a little unusual for the drivers, but we're a small group and just starting out.

|

|

|

|

Left: Lunch in Mukaturi consisted of tibs and injera, a fermented, slightly sour "pancake" made from the grain tef. Pieces of the injera are torn off and used to scoop, dab, or gather up whatever dish is ordered — tibs in this case. Center: Most farms and family compounds look orderly, neat and efficient. Manure is stacked high and dried, to be used later as fuel; rocks picked from fields are arranged into long meandering walls (in the background) that any 18th-century New England farmer would admire. Larger stones divide fields and property. Right: The team continues northeast toward the small town of Lemi on the edge of the Blue Nile Gorge, passing tookles, small farms, tilled fields, and harvested grain piled high into bee-hive shapes. |

|

|

|

|

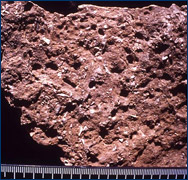

Left: This is not an aerial photo, but the team's first glimpse of the Blue Nile Gorge as seen from the edge of the 5000-meter-thick capping basalt layer. Actually, this is the Jema River valley, a secondary tributary and side canyon to the Blue Nile River, which flows out of Lake Tana further north near Bahir Dar. Right: The unnamed capping basalt layer ranges in age from Quaternary to Early Oligocene. Blocks are mass wasting off the top of the plateau, weathering slowly, and enriching the soils below in the process. Nearly every hillside is terraced and planted. Small villages are marked by green growths of juniper trees within a patchwork of cultivated fields. |

Continuing on our way, we reach the Blue Nile Gorge. Which reminds me, most field projects in Ethiopia, particularly paleoanthropology and archaeologyical ones, have names reflective of their location. The Middle Awash, Hadar, Omo, etc. — ours is the Blue Nile Project. At the very bottom of the gorge, we cross the Jema River, a large meandering system of point bars and channels. The grey rocks of the Lagajima Limestone are exposed by the river down here, but we're after the overlying Mugher Mudstone. The mudstones are deposits from lagoons and estuaries that formed following the retreat of a seaway and continental subsidence. Above the mudstones are sandstones, siltstones and conglomerates, derived from the sediments left by meandering rivers and streams.

|

|

|

|

Left: At first, the road heading down into the gorge from Lemi is nicely graded …. Center: … but soon the road changes to a jarring, slow ride over irregular and sharp blocks of basalt. Right: A new bridge now crosses the Jema since Mark was last here in 1998, but all else looks pretty much the same. This view to the east reveals acacia woodlands and low shrubs growing beyond the banks of the river. |

Not long after crossing over the Jema River, we stop at the Jema VP-1 locality, also called Jema North, a site where the Mugher Mudstone is well exposed below a prominent hill along the road. A small, corrugated steel home sits on the summit now. It was here, on my first visit to Ethiopia in 1993, with Chuck Schaff (Harvard University) and C.B. Wood (Providence College), that we found vertebrate fossils — turtles, crocs, sharks, many fish teeth, and evidence of the first dinosaur known from Ethiopia.

We crawl about the surface for about an hour, picking up surface bone that has weathered out. Then it's time to get back in the Landcruisers and head for Alem Ketema, the town where we'll be staying while we work in the area. We drive out of the gorge and it's dark by the time we arrive in Alem Ketema around 7 pm. We check into a "hotel," then walk through town looking for a place to get some dinner. The first place we check out is full — I recognize the matriarch who runs it from my 1993 visit — the years have not been particularly kind to the place. Options are few here and we settle on a small restaurant and bar in town. Sheep and goat bones litter the floor and the previous diners' scraps of injera and tibs cover the tables. We're skeptical … but we're hungry, thirsty, and tired and order dinner anyway. Back at our lodgings, we find the concrete-block roadhouse to be a bit dusty but adequate. We settle in for the night.

|

|

|

|

Left: At the Jema VP-1 locality, Greg, Chalachew, and Randy (Randy appears slightly larger than life because of the camera angle) are happy to be out of the vehicles and are ready to collect some fossils. Center: In a quiet corner of a cafe near Alem Ketema's main square, Greg and Randy catch up on their field notes. Right: A local herdsman and his family on their way to their village pause to question the strangers. Communication was easy enough even though nobody spoke the other's language. Mark's team is looking for a way to get the Landcruisers as close to the JEM VP-5 locality as possible. |

January 18-19, 2008

|

The view from JEM VP-5 looking south toward the Jema River and across the valley to the plateau. At this locality, abundant microvertebrate fossils are found in different layers representing individual lags deposited by rivers and streams. Many of the mudstone blocks littering the surface are densely packed with fish teeth and bones, shark teeth, dinosaur teeth, and suspicious looking hollow bones that are possibly bird or pterosaur. |

After finding some coffee and bread for breakfast, Chalachew and I head over to the local Culture and Tourism office to check in with the authorities. The head person in the office is not sure about our permission letter from the ARCCH and makes a few phone calls both to Addis and the regional office in Bahir Dar — we plan to visit Bahir Dar after our work here is finished as it's "sort of on the way" to Tigrai and the Adigrat Formation. The official seems unhappy. After much discussion, a letter is drafted, typed, and we are asked to hire a local representative for the time we work in and around Alem Ketema. The local representative turns out to be Tadesse, the official who had seemed reluctant to give us permission. All is well now — we have our letter of permission and are ready to head back down into the Jema River valley.

Back in the gorge, we search for a road that brings us closer to the locality known as JEM VP-5. "JEM" refers to the Jema River that flows just to the south of us here; "VP" stands for Vertebrate Paleontology (we use "PB" for paleobotanical collections); and the "5" means that it's site number 5 out of 15 recorded. Paleontologists give names like this to fossil localities and enter them into their field notes. They also record field numbers assigned to fossils collected, and geo-reference sites using a GPS (Global Positioning System) receiver. So, what’s so special about JEM VP-5? This site, in the Late Jurassic Mugher Mudstone, has an unusually rich concentration of a diverse assemblage of microvertebrate fossils, including fish, sharks, dinosaur teeth, turtle, and mammals. The bones of Late Jurassic mammals are incredibly rare in Africa — only about six teeth are known from the entire continent, and we found one here in some rock samples borrowed in 1998. Greg Wilson is an expert on Mesozoic mammals and he is keen to find more here. Once we relocate the site, our plan is to collect about 1000 pounds of rock and ship it back to UCMP. There we'll break down the rocks by soaking them in water, with a little dilute acetic acid added to dissolve the carbonate cement that holds them together. Then, using small brushes and tweezers under a binocular microscope, the remaining fossil-rich concentrate can be picked through by hand, the tiny fossils being easily identified and sorted.

We are successful in locating JEM VP-5. We spend the rest of the afternoon and the following day studying the site and start to collect bags of sediment.

|

|

|

|

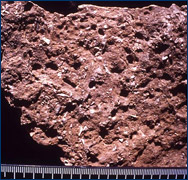

Left: Chalachew and Greg at JEM VP-5 find a rock rich with fossils. This is Chalachew's first trip to the Mugher Mudstone. Center: A close up view of the rock found by Chalachew and Greg. All the white flecks in the rock are bones and teeth of microvertebrate fossils. Right: The cover page of a journal article by UCMP paleontologist and emeritus professor Bill Clemens, Mark, and members of the field crew that first worked in the Mugher Mudstone of Ethiopia. The photograph is of a tooth from Ethiopia's oldest mammal, discovered on Mark's 1998 trip. The scale bar is 1 mm, so you can appreciate just how small these shrew-like mammals were. They lived in what was then the southern continent of Gondwana some 150 million years ago during the Age of the Dinosaurs. |

January 20, 2008

The most efficient way to collect from a microvertebrate locality like JEM VP-5 is to take away lots of bone-rich rocks … and I mean lots of rocks. We figure you need at least a half a ton to realistically assess how rich the site is and how many mammal teeth the site might yield. After all, those small samples borrowed in 1998 yielded hundreds of fish teeth, dozens of dinosaur teeth, and one very small, but scientifically significant, mammal tooth.

We spend a day hand-quarrying and selecting samples from the bone-bearing horizons to take with us. And we continue filling the bags we were overcharged for in the Addis Mercado when we first arrived — but they're an absolute necessity for work like ours so they were worth the expense.

|

|

|

|

Left: Randy carefully inspects the sediment for fossils while Tadesse checks in with his office — yes, there is cell phone service here. Randy will make use of his undergraduate degree in geology when he gets back to Berkeley — he'll be doing analysis and thin sectioning of some of the rock samples. Center: Greg and Tadesse collect samples rich in microvertebrate fossils at JEM VP-5. At the end of the field season, the rocks will be shipped to Berkeley, then processed and sorted to recover the small bones and teeth preserved in them. Right: Greg at JEM VP-5, dressed and ready for some serious collecting. Knee pads … check; cheaters (magnifying glasses) … check; steely-eyed attitude … check. For anyone like Greg who studies Mesozoic mammals, the potential of this site is enormous, but mammals from this time period are incredibly rare in the southern continents. Still, the team has high hopes. |

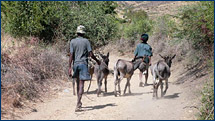

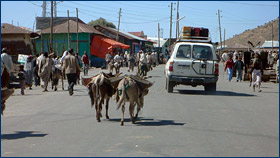

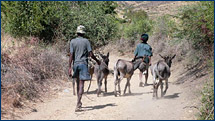

Collecting a half ton of rocks is one thing, but carrying the 20 bagfuls out to our vehicles is another. So we engage some locals with donkeys for hire. Loading up the donkeys and herding them to the Landcruisers isn't easy but we manage. Back in Alem Ketema, the bags are offloaded to a Department of Geology vehicle from Addis Ababa University. Chalachew arranged for a driver to bring our half ton of matrix back to the Geology Department where we can pick it up when our field work is completed. This is a huge relief as I wasn't really sure how we'd continue our work to the north with all those bags of rock weighing down our Landcruisers and taking up space.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

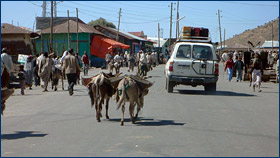

Top left: The team engaged these locals and their four donkeys to transport the bags of rock samples from JEM VP-5 to the cars. Top center: Even donkeys can only carry so much. Two trips are required, with each donkey taking three bags to start. Greg is instructed to hold the donkey's ears — apparently this keeps the donkey under control. Top right: The donkeys were stubborn little guys, but they were up to the task. Each bag weighed about 60 to 70 pounds. Bottom left: Mark's turn to hold onto the ears while a donkey has its load strapped down. The straps are rubber strips made from old tires — the sandals that most of the locals wear are made from old tires too. Bottom center: The donkeys take the samples on the first leg of their journey back to UCMP for analysis. Bottom right: By the end of the day, all the bags have been offloaded and reloaded into the Landcruisers. They'll be transported back to the Geology Department at Addis Ababa University and stored there until the team's return from the field at the end of the month. |

January 21, 2008

|

|

|

|

|

Left: The Menshcen für Menschen cafeteria, essentially a small restaurant with outdoor seating in the tookle. Very pleasant. Right: The team heads out to look for more fossils at other localities in the Mugher Mudstone. |

After a long, hot, dusty day in the field, we head back to town. Camping in our field area down in the river valley would be more convenient, but we are advised against it. We get a tip about the nearby compound of Menshcen für Menschen, a German aid organization providing training and educational programs to people in the rural regions of Ethiopia — they might have a guest house to stay in, so we locate their office and arrange to rent rooms for the remainder of our stay in the area. Our unit (with electricity) is quite nice, with bedrooms, bathroom, shower, kitchen, and a large room perfect for laying out maps or working on field notes and fossils. The grounds are green, with juniper and eucalyptus trees everywhere. A technical college is nearby. We buy some pasta and fresh vegetables in town and make a decent dinner. Life is good.

In Mark's next update, the adventure continues as Mark, Randy, and Greg look for fossils in other parts of Ethiopia.

|