In this issue:

- Director's Letter

by Charles Marshall

- A new and improved Understanding Evolution

by Anna Thanukos

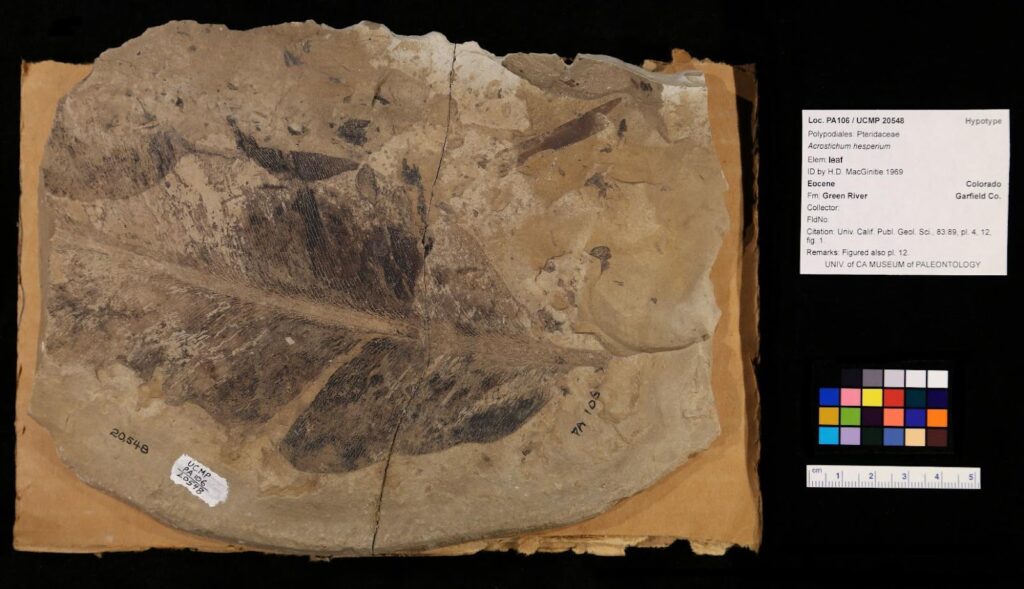

- Pteridophyte Collections Consortium TCN: 2021 digitization update

by Diane Erwin

- Grand Canyon Paleobotany

by Cindy Looy and Ivo Duijnstee

- Emeryville and Richmond Shell Mounds

by Jere Lipps

- Updates from staff, students, and curators

- ACCESS Program still going strong!

by Josh Zimmt and Lisa White

- UCMP's 100th Jubilee Celebration

- Friends of UCMP

Director's Letter

Holiday greetings to you all! It is hard to believe we are nearing the end of the second year of the pandemic. The protracted isolation has been particularly hard on the students, but as we have moved back to in-person classes, their morale improves. We are looking forward to healthier times. Despite the complications that came with Covid, the UCMP has had a very good year. We celebrated our 100th birthday. The UCMP education and outreach team (Anna Thanukos, ably supported by Lisa White, Trish Roque, and Helina Chin) modernized and enhanced the Understanding Evolution website for a new generation of users. The UCMP DEI Anti-racism Working Group continued its work, in part through a fall semester graduate student seminar series on tools for increasing DEI in academia. Important work continued in the collections, through the collaborative NSF-funded Pteridophyte Collections Consortium Thematic Collections Network (PCC TCN) project (with Diane Erwin at the helm of UCMP’s role), an IMLS grant to curate and digitize the UCMP Cambrian and Ordovician collections, including Bill Berry’s graptolite collection (led by Ashley Dineen), and the completion of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission contract to transfer and manage fossils associated with Calaveras Dam Replacement Project under the guidance of Pat Holroyd. And the research activity remained high, some of which is summarized in this Newsletter. Our thanks for all your support of the UCMP, and best wishes to you all. Have a safe & happy holiday season!

A new and improved Understanding Evolution

We’re happy to announce that the modernized and enhanced Understanding Evolution website is now live and ready for a new generation of users! Funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, the project involved a major overhaul of this essential, decades-old resource for teaching and learning about evolution. With guidance from our scientific and teacher advisors, as well as visitor input, we:

- reviewed and updated the content on our most popular pages

- updated images and phylogenies throughout the site

- developed a new feature, Digging Data, to bring authentic evolutionary data onto the website and into the classroom

- and gave the site a sleek new look and improved navigation

Lots went on behind the scenes too. We moved all of our old Flash animations to a modern platform and recreated about a thousand webpages in a content management system, vastly improving the security of the site and making it easier to update in the future, as the Internet continues to evolve.

Explore it for yourself: evolution.berkeley.edu. We hope you like it!

Pteridophyte Collections Consortium TCN: 2021 digitization update

Three years in, the Pteridophyte Collections Consortium Thematic Collections Network (PCC TCN) project is reaching its goal of serving the digitized data of nearly 1.7 million extant and fossil fern specimens via the project’s online Symbiota Pteridoportal (https://www.pteridoportal.org/) and the iDigBio website (https://www.idigbio.org/), despite setbacks due to the Covid-19 pandemic. These sites currently serve 1,685,748 extant records, 12,848 fossil records, 1,419,430 images of extant organisms, and 38,592 fossil images. Thanks to our NSF-funded PCC TCN, the largest collections of extant and fossil ferns in the world, which includes the UCMP and the University and Jepson Herbaria, are now freely web-accessible to researchers and the general public. Visit our website, https://pteridophytes.berkeley.edu/ for more information, and follow us on Twitter (@pterido_TCN), Facebook (@pteridophyteTCN), and Instagram (pteridophyte_tcn).

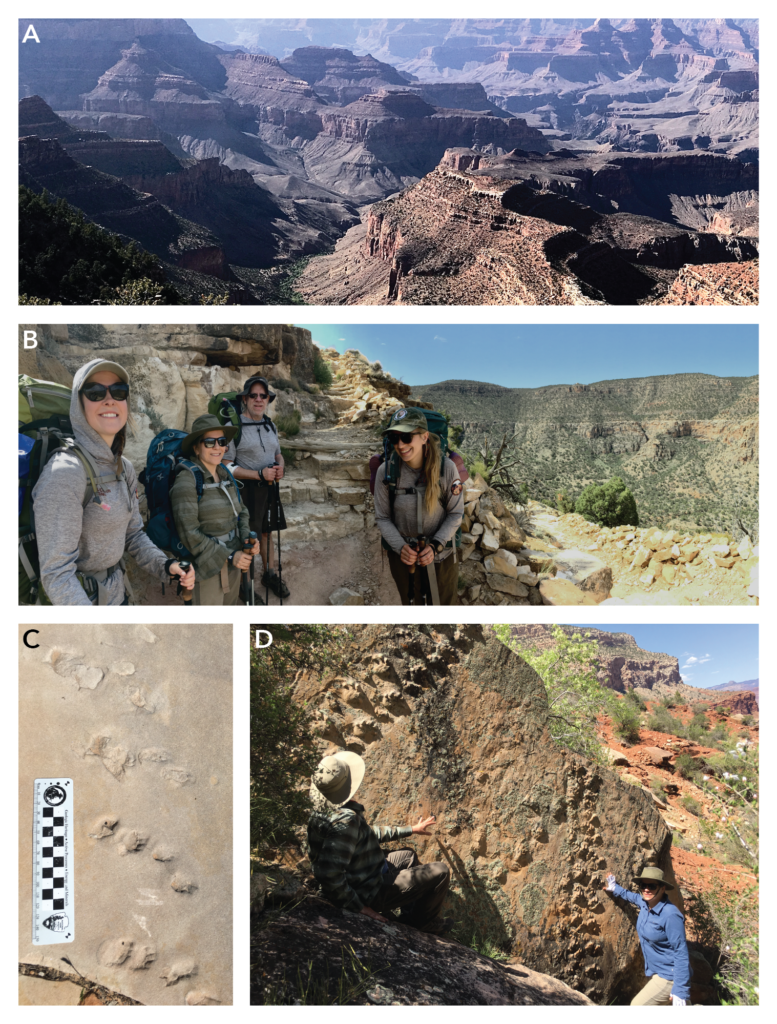

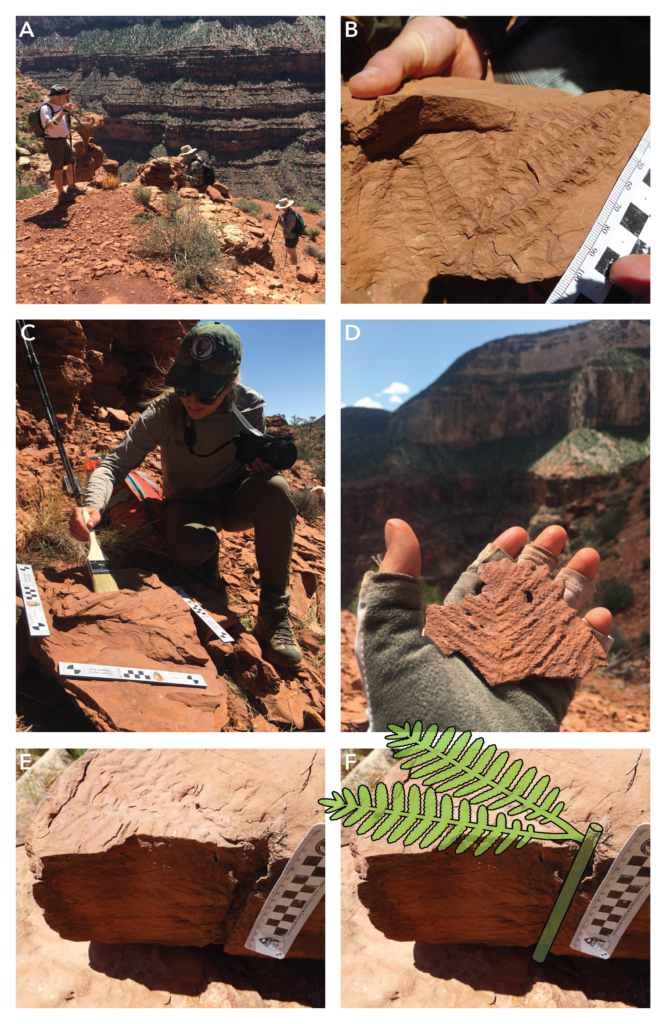

Grand Canyon Paleobotany

The Grand Canyon is well known for its early Permian plant fossils, but strangely enough, few paleobotanists have explored the canyon since David White’s book “Flora of the Hermit Shale” was published in 1929. Recently, a team of Grand Canyon National Park paleontologists started new field explorations and significantly expanded the number of known fossiliferous localities. They started with the localities from which White obtained his fossils and expanded the search laterally along the famed Hermit and Boucher Trails. It seems that everywhere they looked, the Hermit was teeming with plant fossils. Needless to say, after being cooped up for more than a year, we (Cindy Looy and Ivo Duijnstee) jumped at the opportunity to join the Grand Canyon paleontology team on a field trip in May this year.

After spending some time in the collections at the park’s headquarters with park paleontologists Mark Nebel, Anne Miller and Erikka Olson, we had one good night’s rest at one of the guesthouses. The following morning, we started our descent into the canyon, our packs filled with freeze dried meals, salty snacks and lightweight field gear. Just below the rim, we immediately walk back in time, ever deeper into the Permian. Hiking down the rocky and steep Hermit Trail, we passed marine beds in the Kaibab Limestone, rich in sponges, brachiopods, bryozoans, echinoderms and rugose corals. After passing through the much thinner Toroweap Formation, we walked down the steep depositional surfaces of the old Coconino sand dunes. The same slopes had been traversed by late Paleozoic critters, leaving their footsteps everywhere—ranging from tiny arthropods to massive diadectomorph tetrapods.

After several hours of looking at fossils on the way down, some 500 m below the canyon’s rim, we arrived at the base of the Hermit Formation. Although often called Hermit Shale, the sediments are actually dominated by reddish mud and siltstone, laid down by a river system in a semi-arid climate. Amidst the junipers, ephedra, sagebrush and cacti, we found enough flat areas to pitch our tents and set up camp—our field “living room” —an empty river bed. With no water on site, most of our water was carried down and cached by the Grand Canyon paleo team ahead of time. To prevent uninvited dinner guests, our food was stored in critter proof bags dangling from the juniper trees.

In the following days, we visited the newly discovered plant sites. Most rocks are way too big and heavy to haul back up, thus photogrammetry was used to record the most important specimens. The best plant fossils were found in the areas where Hermit channels had cut into the underlying Esplanade Sandstone of the Supai Group. The flora is dominated by seed plants and includes supaias and callipterids (so-called seed ferns), complemented by representatives of more familiar plant groups: walchian conifers, taeniopterids (likely early cycads) and Sphenophyllum spore plants (horsetails). The plants in these localities are not necessarily preserved in fine detail, but will give us new crucial information about their growth form. They are frequently found standing up in life position and with various plant organs (e.g., leaves, branches, etc.) still attached. This makes the Hermit flora quite exceptional, since most fossil floras consist of preserved, often dispersed plant organs. Erikka, Anne and Mark are not yet done exploring the extent of the Hermit Flora (both taxonomically and geographically), but we can’t wait to see a much overdue addition to White’s seminal work from almost a century ago.

Emeryville and Richmond Shell Mounds

During the lockdown, Professor Emeritus Jere Lipps explored the Emeryville and Richmond Shell Mounds, which were built 3000-4000 years ago. The Shell Mounds rest in the territory of xučyun (Huichin), the ancestral and unceded land of the Chochenyo speaking Ohlone people, the successors of the sovereign Verona Band of Alameda County. The land was and continues to be of great importance to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and other familial descendants of the Verona Band.

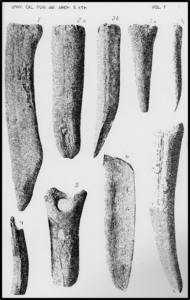

The shellmonds were investigated during 1902 to 1928 by J. C. Merriam, the first paleontology professor at Berkeley, and teams of assistants he supervised. Under Merriam’s direction, a survey around San Francisco Bay showed over 425 mounds. The excavation was not done like modern archaeological digs, rather, more like a paleo dig looking for fossils. The mounds contained the living sites of the people and their food debris, hence the huge accumulation of shells although bones of birds and mammals were common too. They recovered tools, documented burials and village sites, and other evidence of life from 4000 until about 500 years ago.

In 1928, Hildegrad Howard, who later became a leader in bird paleontology and was Director of the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History, published her UC dissertation on the bird remains from the Mound. From the species occurrences, she determined that the people lived on the mounds seasonally, chiefly in spring through summer, and moved towards and into the mountains nearby in the fall and winter.

The Emeryville mound was one of the largest. None of the mounds exist as they were at the time of Merriam’s survey – they have been degraded and destroyed by excavation, industries and development. The Emeryville site is covered by a shopping mall and hotel. A monument constructed by descendants of the Huichin and other tribes calls attention to their sacred site with a small representation of the way the mound looked originally and with a walkway lined by stones engraved with the story of their people and mounds. The work done by Merriam’s crews documented much about the mounds before they were totally destroyed. Merriam’s work as an archaeologist is not commonly known in the paleo world but is a fascinating story of the breadth of his interests. In this same time period, he was busy at John Day fossil beds in Oregon, on the Saurian Expedition to Nevada, and at Rancho La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles collecting tons of fossils that UCMP has in Valley Life Sciences Building and the Campanile (four of the five floors hold tar pit fossils).

Updates from staff, students, and curators

Ashley Dineen, PI on an IMLS-funded project to curate and digitize the UCMP Cambrian and Ordovician collections shared in the first year, she and a team of students have digitized almost 2,700 Cambrian and Ordovician invertebrate lots, consisting of over 7,500 individual fossils, and they photographed over 500 type specimens. People can follow our progress on twitter at @Ordovician_IMLS. Ashley also found time during a busy year to be the new Chair of the Paleontological Society’s Cordilleran Section.

Carole Hickman submitted a 50-page analysis of anomalous surges and contractions in arcoid bivalve biodiversity during the Eocene “doubthouse” interval of global climate change; completed part III of the Keasey bivalve monograph; is working with former UCMP PhD students Liz Nesbitt and David Taylor on a new Eocene methane seep in Oregon, and continues to participate in the Coaledo Project, with results to be featured at sessions in Portland at the upcoming in-person GSA meetings along with a field trip to Coaledo Basin outcrops on the Oregon coast.

The Calaveras Dam project continues to curate marine fossils under the supervision of Senior Museum Scientists Pat Holroyd and Ashley Dineen, with contributions from a team of UCMP staff and students. The SF Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) provided an additional $120,000, for a total project amount of $595,000. A multiyear project, the second amendment executed on June 30, 2020 extended the project to March 31, 2021. Then, due to the pandemic and the campus closure, a third amendment extended the project to December 31, 2021. The extensions allowed for continued curatorial activities, completion of deliverables, storage, and curation of fossils collected during the dam construction and subsequently donated to the UCMP. UCMP is grateful for Mark Goodwin’s initial leadership on the project that secured the funding by the SFPUC. We thank SFPUC Regional Project Manager Susan Hou and Biologist/Permitting and Environmental Compliance Manager JT Mates-Murchin for their long-term interest in the protection and conservation of the fossil discoveries from marine Miocene sediments within the Calaveras Dam project area, Alameda and Santa Clara Counties.

Together with three international colleagues, Cindy Looy received a Human Frontiers Science Program research grant to study Teratology in microfossils as a proxy for understanding mass-extinctions through time. Cindy is also a co-PI on a new NSF-funded Research Coordination Network titled Ecological and evolutionary effects of extinction and ecosystem engineers. The network will start off with a December meeting in Berkeley.

Kevin Padian, Curator Emeritus, co-edited a new Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir on the Late Cretaceous pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus. The eight articles in the Memoir shed new light on bones collected from Big Bend National Park in the 1970’s by Douglas Lawson who would later obtain his PhD at Berkeley. The SVP Memoir is highlighted in Berkeley News. Data and interpretations from scientists and illustrations from artists provide fascinating information on pterosaur anatomy, movement, and feeding styles.

Jack Tseng taught a freshman seminar during the Fall 2021 called “Extreme Mammals!” using the UCMP teaching collection. This is one of several courses planned in vertebrate paleontology (with a non-majors dinosaur course in Spring 2022, another freshmen seminar in Fall 2022, and upper division vertebrate paleontology the Spring after) that will leverage UCMP teaching collection to bring vertebrate paleo to more Cal students. Jack is shown holding an Orca jaw next to a T. rex tooth for scale.

Lisa White was named to the Board of Directors of the Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research in early 2021 on the recommendation and nomination by Jere Lipps who has advocated for more diversity in representation on the Board. In September 2021 Lisa was also honored by the National Association of Geoscience Teachers with the Neil Miner Award. The award is given annually to an individual for exceptional contributions to the stimulation of interest in the Earth sciences.

Sara Kahanamoku (Finnegan Lab) co-authored a Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America paper, “Who are we? Highlighting nuances in Asian American experiences in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology,” focused on common issues that Asian American authors face in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and steps to address anti-Asian racism in STEM institutions.

Jenn Wagner of the Looy Lab made a trip to collect fossil leaves of Eocene age from several clay mines in Tennessee and Kentucky. The leaves were deposited during one of hottest periods in the Phanerozoic when subtropical plants persisted and thrived at higher latitudes. Collecting fossils with Jenn was Josie Christon, a recent graduate from UC Berkeley and now part of the UCB’s Earth and Planetary Sciences MS program. They were joined by Professor Lauren Michel from Tennessee Tech University, and Britney McGuire, a graduate student at Tennessee Tech. In the group photo, Lauren, Jenn, Josie, and Britney sit on top of fossil deposits in one of the mines, which are owned and operated by the Hickory Clay Mining company. While collecting fossils, Jenn performed systematic census collections and collected more than 300 specimens, 60 of which are located in the Looy Lab waiting to dry. The rest of the specimens remain at Tennessee Tech until Jenn returns. The plan is to return soon, with more people, to conduct more census collections and uncover more fossil treasures!

We are also happy to report that Looy Lab alumnus, Dori Contreras, Curator of Paleobotany at the Perot Museum in Dallas, gave birth to a baby daughter in August 2021. Photo is of parents Dori and Adam with son Andreas and daughter Liana.

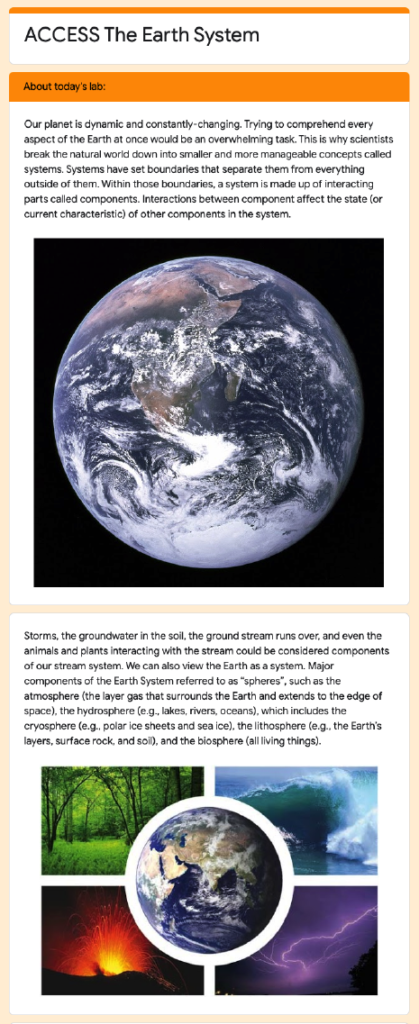

ACCESS Program still going strong!

The ACCESS (Advancing Community College Education and Student Success) program at the UCMP partners with community college faculty to design and facilitate paleobiology and geology lessons. ACCESS began as a local program that invited Bay Area community college classes to UC Berkeley to complete specimen-based labs featuring UCMP fossils. The program quickly expanded due to the need for specimen-based learning, which is critical for engaging students in the paleo- and geosciences. However, the COVID-19 pandemic posed a major obstacle to the continuation of the ACCESS program. The question soon became if and how the program could continue if in-person classes could no longer run.

Starting in Summer 2020, UCMP graduate student Josh Zimmt led the creation of a digital ACCESS program, creating eight brand-new online ACCESS labs in collaboration with graduate students and faculty from across UC institutions. As of the end of the 2021 calendar year, these labs have been shared with more than 30 community colleges institutions around the country, reaching an audience of over 1,250 students. The program continues to grow and expand in new directions: an NSF grant awarded to Lisa White, Jessica Bean, and Josh Zimmt will support a one-year virtual workshop series and Professional Learning Community (PLC) of community college instructors and graduate students. The goal of the PLC is to support the development of teaching resources for diverse audiences through the implementation of equitable and inclusive teaching practices.

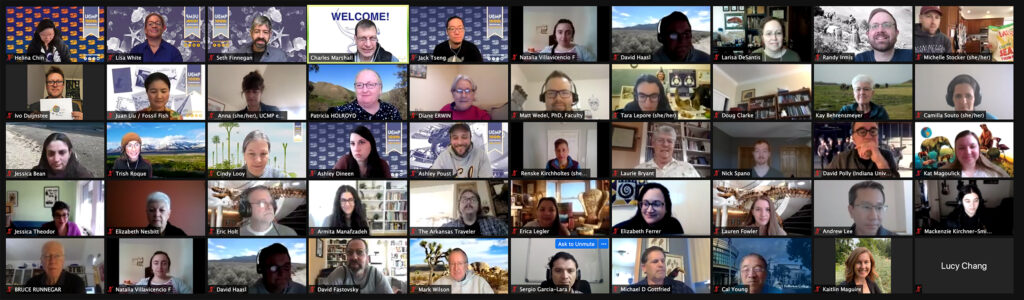

UCMP's 100th Jubilee Celebration

UCMP celebrated a milestone birthday in 2021! On March 14, 1921, the museum was officially founded when the campus accepted a generous sum from UCMP benefactor, Annie Alexander. We marked the occasion with a virtual celebration on March 13, 2021. Attended by over 70 UCMP alumni and friends, and current students, staff and faculty, we thoroughly enjoyed the event and the many ideas shared.

During discussions in breakout rooms we invited opinions on: (1) what the future trajectories and dimensions in paleontology will be (responses are captured in the “word cloud” on the lower left) and (2) ways the UCMP can capitalize on our strengths to succeed in the future (responses are captured in the “word cloud” on the lower right).

We look forward to UCMP’s next hundred years and many future opportunities to gather in-person and virtually.

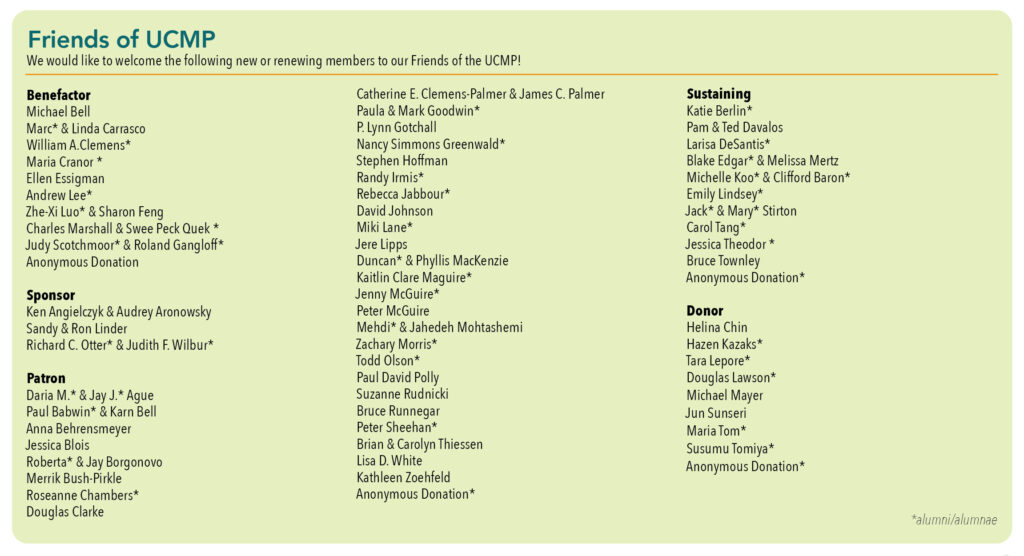

Friends of UCMP

The UCMP thanks its Friends for supporting us over the last year. We greatly appreciate your contributions towards our mission!