In this issue:

- Kenneth L. Finger Retires

A review of the work of micropaleontologist Ken Finger by Jere Lipps.

- Director's Letter

A few words from the Director of the UCMP, Charles Marshall.

- Student Awards, Honors & Updates

Updates on the work of UCMP students and their awards

- Faculty in the Spotlight

News regarding faculty activities.

- UCMP's 2017 Basin & Range field trip

Essay and Photos from the UCMP Graduate Student Summer 2017 Fieldtrip by David K. Smith

- Cal Day 2017 at UCMP

A recap of UCMP's activities during Cal Day 2017!

- What's new in the collections

Updates on our EPICC Program

- Staff Updates

Staff updates featuring iDigBio and a research cruise in the southern hemisphere.

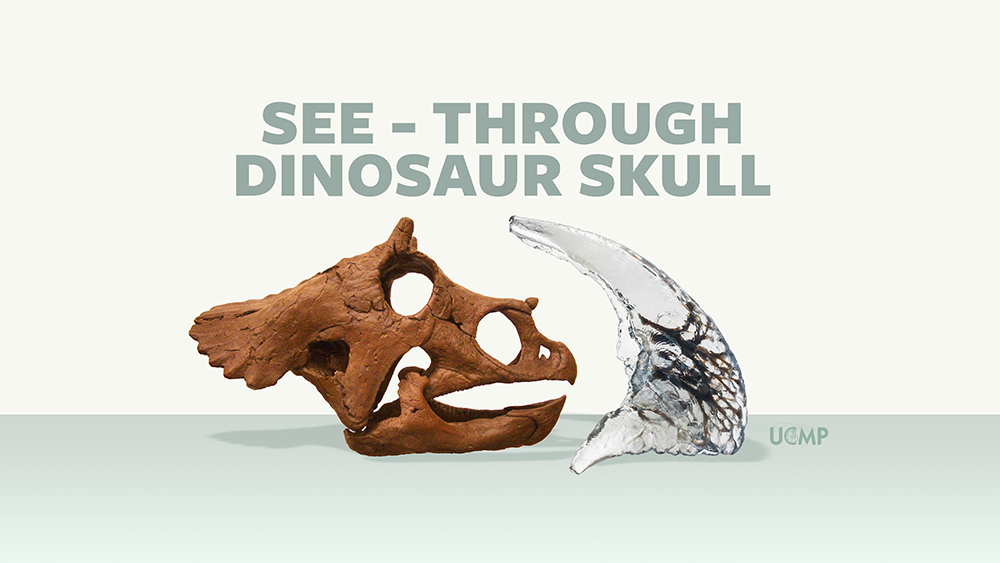

- See-Through Dinosaur Skull

Many thanks to our supporters for this Crowdfunding effort!

- Friends of UCMP

Thanks to the UCMP benefactors.

Kenneth L. Finger Retires

Written by Jere Lipps

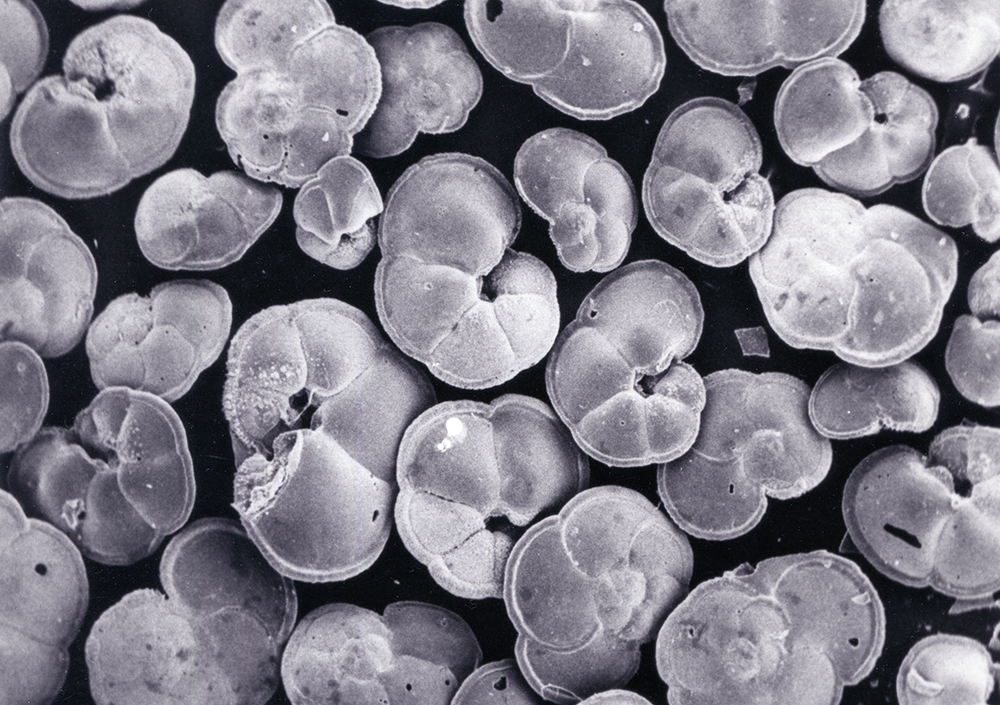

Ken Finger, a kid from New York City, was introduced to paleontology at State University of NY, Stony Brook, in the early 1970s. Wanting to do a PhD in paleo, he was accepted to the new paleobiology program at UC Davis in 1972. There he started an MA thesis on foraminifera from the active Antarctic volcano, Deception Island, which was judged by his committee to be so good that with a little more work he could turn it into a PhD dissertation. He did that, and graduated in 1976. In that same week, he got married and received a job offer as Exploration Paleontologist at Chevron USA, New Orleans. Three years later, he was promoted to Senior Research Geologist at Chevron Oil Field Research Company in La Habra, CA. While in Southern California, Ken also worked in mitigation paleontology and taught geology, paleontology, and oceanography at local colleges.

His research position at Chevron allowed him to begin his long career in publishing critical papers on microfossils. His dissertation was published in 1981 with J. H. Lipps on Foraminiferal decimation and repopulation in an active volcanic caldera, Deception Island, Antarctica†in Micropaleontology. Ken continued his record publishing rate of at least one paper almost every year since 1981 for a total of 56 peer-reviewed papers, 4 books and scads of abstracts, mostly on foraminifera, but also on other groups of microfossils (diatoms, silicoflagellates, calcareous nanoplankton, and invertebrates: ostracods, barnacles, polychaetes, chitinozoa). His focus was not just on the fossils but on biostratigraphy, isotope geochemistry, tectonic settings and paleoenvironments. In this role, he emerged as the foremost expert on American West Coast Miocene foraminiferal biostratigraphy from Chile and north to California. Ken’s papers were well known as thorough, detailed, carefully designed, abundantly illustrated, and among the most useful of works.

From 2002 to 2017, UCMP was fortunate to have Ken (and his research programs) as Senior Museum Scientist & Manager of the extensive microfossil collection of millions of specimens and thousands of samples from all over the world. Only a truly dedicated professional micropaleontologist whose main desire and aim was to get all the major UCMP microfossil collections in proper order so they could serve the profession and students long into the future, could deal with the massive UCMP microfossil collection. While Ken accomplished that for much of the collection, he regretfully retired without finishing all, a task he himself said would take another 100 years or so. Fortunately, Ken will remain a Museum Associate, and thus available to assist in microfossil curation and research.

Director's Letter

I write to you as the new year begins: classes and seminars will soon start, and our new graduate students will learn how to use the collections, beginning their new path as future UCMP alums! Sadly, our collections will be a little bit quieter with the retirement of Ken Finger after 15 years of deep service to UCMP, adding order to our vast microfossil collections – fortunately his contributions will not go unpunished, with Jere Lipps leading the celebration of Ken’s career at our first Fossil Coffee of the year.

I write to you as the new year begins: classes and seminars will soon start, and our new graduate students will learn how to use the collections, beginning their new path as future UCMP alums! Sadly, our collections will be a little bit quieter with the retirement of Ken Finger after 15 years of deep service to UCMP, adding order to our vast microfossil collections – fortunately his contributions will not go unpunished, with Jere Lipps leading the celebration of Ken’s career at our first Fossil Coffee of the year.

Over the summer many have been in the field (including yours truly who found the first ever living specimens of a species of infaunal echinoid, a cassiduloid, that was only known from dead tests), Erica Clites has been consolidating the NSF multi-institutional EPICC digitization project that now begins the 3rd of its 4 years, and we are excited to have just hired Cristina Robinson San Francisco Public Utility Commission’s (SFPUC) dime as she reopens the fossil preparation lab so that we can process fossils coming from the Calaveras Dam site. And while Lisa White was teaching teachers on an IODP Expedition in the Equatorial Pacific, Jessica Bean has been forging relationships with HHMI, NOAA, Google, and others as our Understand Global Change web resource nears its launch, with funding coming in part from a very generous $100,000 gift from an anonymous donor. On the Berkeley campus, we now have inspired leadership dealing with the budget challenges, but our State funds continue to dwindle. However, recent gifts have all but secured our ability to support our graduate student research (thanks to all that have given), and so now I am turning my long-term planning to securing the funds needed to maintain our exceptional collections and education and outreach staff – a daunting task, but one we must face head on if we are to secure and continue building on UCMP’s legacy.

Sincerely,

Charles Marshall

Student Awards, Honors & Updates

Jeffrey Benca has won this year’s Louderback Award in paleontology. The Louderback Award is given annually to one or two students in paleontology and in Earth science. Recipients exemplify the values of scholarship, teaching and leadership set by the venerated Professor George D. Louderback. Jeff is implementing studies of living plants to test hypothesized drivers of mass extinctions and environmental changes in the deep past.

Lucy Chang completed her dissertation this summer and is now a Peter Buck Deep Time Postdoctoral Fellow, a two-year research fellowship with dedicated time for advancing science education at the Smithsonian. Her time will be split 75% research, 25% education with funds provided by the Smithsonian Deep Time Initiative. She will continue research tying morphology to patterns in origination and extinction using their incredible collection of Cretaceous ammonites.

Sara ElShafie was awarded the Charles A. and June R.P. Ross Graduate Student Research Award from the GSA, for research on the “effects of climate changes on the earth’s inhabitants through geologic time.” She received a Graduate Student Research Grant from the Evolving Earth Foundation and was selected to attend the National Communicating Science Conference, the “ComSciCon,” in June.

Incoming graduate student, Sara Kahanamoku-Snelling was awarded a prestigious NSF Graduate Research Fellowship. A 5-year award, Sara comes to the UCMP from Yale and will begin in fall 2017.

Peter Kloess has a new paper in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimaology, Palaeoecology: Kloess, P. A., & Parham, J. F. (2017). “A specimen based approach to reconstructing the late Neogene seabird communities of California.” Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 468, 473-484.

Jun Lim was awarded a graduate fellowship to do research at the Smithsonian NMNH this summer, and he spent part of the summer in the Hawaiian Islands looking at Pacific Piperaceae. Jun and Charles recently published a paper on the Hawaiian archipelago: Lim, Jun Y., and Marshall, Charles R., “The true tempo of evolutionary radiation and decline revealed on the Hawaiian archipelago.” Nature 543 (7647) 2017: 710-7.

Tesla Monson is happy to report that she finished her PhD (on The Sequence of Postcanine Tooth Eruption in Mammals) in May and she will remain at UCB during the 2017-18 academic year as a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer.

Camilla Souto was invited to participate in the 2017 Bodega Applied Phylogenetics Workshop, offered by UC Davis and held at the Bodega Marine Lab. The workshop discussed topics in statistical Phylogenetics, and had 10 instructors and 33 students from all over the world. During the workshop she used her Cancer crabs’ dataset but will also apply what she’s learned to her echinoid dataset.

UCMP alum and Virginia Tech Assistant Professor Sterling Nesbitt has been awarded the Donath Medal (Young Scientist Award) from the Geological Society of America. He will receive the award at the GSA Annual Meeting in Seattle in October 2017.

Postdoctoral scholar Adiel Klompmaker recently received a Paleontological Society Arthur James Boucot research grant for early career (postdocs and assistant professors) for field work in Cyprus and collection-based researc

h in the Netherlands, Austria, and Florida.

Faculty in the Spotlight

A two-volume set of transcribed interviews of Bill Clemens and his former students were presented to Bill during UCMP’s weekly “Fossil Coffee” seminar at the end of the spring semester. The Clemens Oral History volumes include interviews from Bill’s students and colleagues including Bill’s first PhD Student Jay Lillegraven (Univ. of Wyoming) at Univ. of Kansas to his last Greg Wilson (Univ. of Washington) at UC Berkeley. Paul Burnett of the Bancroft Library’s Oral History Center was the interviewer and lead archivist on the project. At Fossil Coffee, he provided an overview of the project’s uniqueness while previewing videos of both Bill and the interviewees. In the near future, the video transcriptions and excerpts of videos will be hosted on the UCMP website. We thank Bill, the Clemens family, and the many donors who generously contributed to the project.

Seth Finnegan was recently awarded a new NSF grant: Pleistocene to Recent Environments and Species Distributions on the California Coast together with UCMP Postdoctoral ScholarJessica Bean.

Charles Marshall continues to challenge the biological community to properly integrate our paleontological knowledge into their analyses of current biodiversity, most recently with a paper entitled “Five paleobiological laws needed to understand the evolution of the living biota”, published in Nature Ecology and Evolution (2017; 1: 0165).

Cindy Looy received a new NSF Collaborative Research grant entitled: A Unique Window into the Ecology of Cretaceous Forests during the Rise of Angiosperms. The grant will further the research of Cindy and graduate student Dori Contreras on exceptionally preserved fossil floras. The grant will also support a new public exhibit on the 2nd floor of the Valley Life Sciences Building.

At the southern tip of peninsular Malaysia, a sea grass meadow and world marine biodiversity mega hotspot, Julia Sigwart (UCMP Visiting Scholar) and colleaguesfrom Malaysia and Japan recently led a training workshop in molluscan taxonomy. Participants included graduate students and junior faculty from universities across Malaysia and Singapore, as well as several members of an environmental kids club that is developing ecotourism with local youth.

During February and March, Curator and Professor Emeritus Jere Lipps gave six lectures, from “PaleoParks”, extinctions, and astrobiology at universities, institutes and paleontological laboratories in India. He spoke at the annual meeting of the Palaeontological Society of India at the Wadia Institute for Himalayan Geology in Dehradun, at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences in Lucknow, in Varanasi at the Baranasi Hindu University, at Pune University, and the National Institute of Oceanography in Goa where he also visited Professor R. Nigam, an acclaimed micropaleontologist, and his students and post-docs. While in Pune, he also visited the Deccan site.

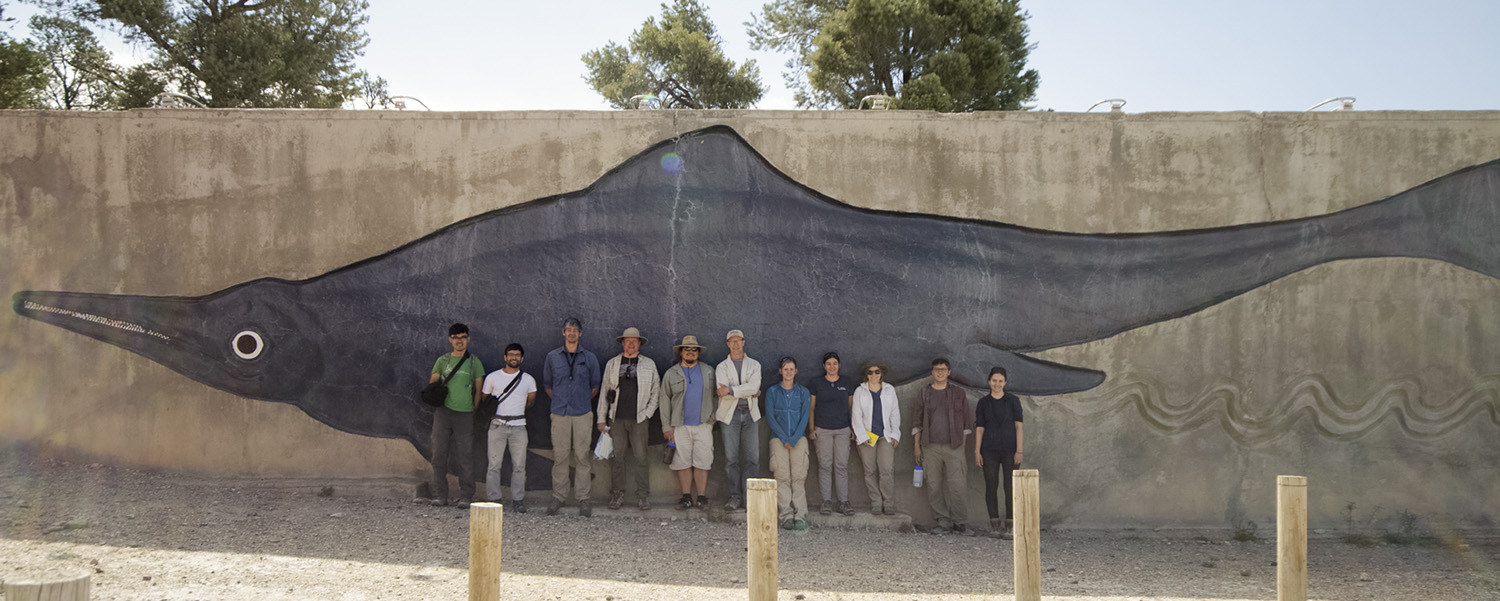

UCMP's 2017 Basin & Range field trip

by Dave Smith, with contributions from Seth Finnegan; all photos by Dave Smith unless otherwise indicated

Why have field trips? Department of Integrative Biology professor and UCMP curator Seth Finnegan summed it up nicely when he said, prior to leading his first UCMP field trip in 2014, “My intent is to provide graduate students who may not have spent much time in the field an opportunity to see fossils in their stratigraphic context, to learn some of the basics of using sedimentology and taphonomy to make paleoecological inferences, and to consider the ways in which paleontological information is filtered through the geological record.” Seth has since co-led three more field trips — now annual events — and his motivation has remained the same.

This year’s field trip took us somewhere entirely new: across Nevada and into western Utah to explore the Basin & Range along the highway 50 corridor. Although I retired from the museum two years ago, I tagged along on this one to once again keep a record of the trip in both words and photos; I had done this for two previous field trips to southern California: 2014 Kettleman Hills & Death Valley and 2015 Monterey Formation & Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. I missed out on the 2016 trip that revisited the Kettleman Hills and Death Valley.

Up until this year, the field trips had been scheduled for the week of Spring Break (March) but this one began at the end of the Spring Semester, the day after the Department of Integrative Biology’s graduation ceremony; we left Berkeley on Sunday, May 21, and returned on Saturday, May 27. Leading the trip were Seth and fellow UCMP curators and professors of Integrative Biology Cindy Looy (co-leading for the third consecutive year) and Ivo Duijnstee (his second year as a co-leader). There was a smaller number of participating students this year — just seven: Peter Kloess (Padian Lab), Daniel Latorre (Marshall Lab), Jun Ying Lim (Marshall Lab), Mackenzie Kirchner-Smith (Padian Lab), Emily Orzechowski (Finnegan Lab), Franziska Franeck (Liow Lab, University of Oslo), and Richard Stockey (Sperling Lab, Stanford University). Jun and Emily were the only veterans of previous field trips (Jun, two, and Emily, four).

Our vehicles — four four-wheel-drive SUVs rented through the Enterprise near campus — and groceries — enough to last us through Ely, Nevada — were picked up on Saturday, the day before our departure. The plan was to meet at the West Circle near the Valley Life Sciences Buiiding at 11:00 Sunday morning.

Sunday, May 21

I was the first to arrive, followed shortly by Franzi. We didn’t have to wait long before Seth and Ivo drove up in two of the vehicles. I jumped into Ivo’s vehicle and we drove back to his and Cindy’s place to pick up another SUV that had been left there. While doing that, the rest of the trip participants, as well as Peter with the fourth SUV, arrived at the Circle. It took a while to load all the supplies, everyone’s gear, water containers and coolers; we didn’t leave campus until almost 12:30 PM. Joining Seth in a white Chevy Tahoe were Daniel and Jun. Peter drove a blue GMC Yukon, and was accompanied by Emily and Franzi. Ivo, Cindy and Mackenzie were in a black Ford Expedition; Ivo and Mackenzie would switch off as drivers. I drove a white Expedition with Richard as my sole passenger. As in the past, each car had a walkie-talkie and, once again, they proved to be very useful, both in pointing out geological features along our route and in general communication between the vehicles.

We headed east on I-80 and made one stop in Roseville for lunch, to fill our tanks, and to get more ice for the coolers before hitting the road again.

Our four SUVs rendezvoused in Fernley, NV, where we followed Seth to the offices of EP Minerals, the mining company on whose land we’d be working the next day; here, Seth dropped off liability waivers for everyone in the crew. Then it was off to the Lake Lahontan State Recreation Area where we’d be camping this first night. On our way there, Seth used the walkie-talkie to let us know that shoreline terraces from Pleistocene Lake Lahontan were visible on the surrounding hills.

At its peak, around 12,700 years ago, Lake Lahontan covered much of western Nevada, extending north into Oregon and west into northeastern California. The only true remnant lakes of Pleistocene Lake Lahontan are Pyramid and Walker Lakes. Modern-day Lake Lahontan is not a true remnant of the ancient lake, but a dammed reservoir, fed by the Carson and Truckee Rivers. Pleistocene Lake Lahontan once covered what is now the Black Rock Desert, where Burning Man is held, to a depth of about 500 feet. Due to climate change resulting in increased evaporation, most of the lake had dried up by 9,000 years ago.

In the Recreation Area, we drove to Silver Springs Beach and set up our tents on a sandy area well above the water’s edge (we’d seen posted signs saying that the lake was rising three to six inches a day because of snowmelt). Jun and Daniel prepared a nice dinner of burgers and corn on the cob. They cooked up all the leftover ground beef and saved it for the next night’s dinner.

Small, black flies tormented us upon arrival at the campsite, but once the sun went down and the temperature cooled, the flies disappeared. We sat out for a while to do some stargazing before heading to our tents. I heard coyotes howling shortly after writing my journal entry and then owls periodically throughout the night.

Monday, May 22

It was light by 5:30 so I began to pack up my things. I could see from their shadows on my tent that the black flies were already active. Seth got up around 6:30 or so to make coffee. We would have had breakfast there, but the flies were so horrible — getting into people’s eyes, ears, noses, and mouths — that as soon as the coffee was consumed, we packed up the SUVs and got out of there.

Our first destination of the day was a diatomite mine east of Fernley and south of Hazen. I thought that the dirt roads leading to the mine were rocky and fairly treacherous, but they turned out to be fairly smooth compared to some of the roads we’d navigate later. Once at the mine, we set up the handy camp table that Cindy and Ivo had brought along and laid out bagels and cream cheese for breakfast. While eating, Seth and Cindy talked about the stickleback fish fossils that are found at this site and how their evolution can be observed over time.

Long before Lake Lahontan — about ten million years ago during the Miocene, when precipitation was higher than it is today — a deep lake covered this part of Nevada. Diatoms — microscopic, planktonic organisms with siliceous tests — thrived in the lake’s waters. When the diatoms died, their tests sank to the bottom of the lake where, over time, thinly laminated, white, chalky layers accumulated, creating a thick deposit of what we call diatomite. Diatomite — diatomaceous earth — is used primarily for filtering liquids, as an additive in such things as paint and plastics, and as an absorbent. Also living in the lake were stickleback fish, whose fossils are abundant within the diatomite layers. Originally, the sticklebacks in the lake had a reduced pelvis and no spines. After about 10.000 years there was a rapid change in the population to a form with both a complete pelvis and spines; this is probably due to a merging with another lake where the complete-pelvis and spine-bearing sticklebacks were common. But in another 10,000 years, the population re-evolved into the reduced pelvis and spineless form; this transition can be seen in the fossil record.

We hiked over a low ridge and into a depression where the layers of diatomite were exposed and spent the next few hours splitting open the layers looking for stickleback fossils. The layers were so thin that putty knives were distributed to split them. Seth found some particularly good specimens.

Following lunch at the cars, we left the mine, headed back up to 50, and then east towards Fallon. There we gassed up, got more ice, and filled our water containers. About 20 miles east of Fallon, Seth directed our attention to an enormous sand dune — at Sand Mountain Recreation Area — to the north of the road. The prevailing winds had built a two-mile long, 600-foot high dune out of sands deposited in Pleistocene Lake Lahontan.

After another 30 miles or so, we left 50 and headed southeast on dirt roads towards Buffalo Canyon, where the famous Buffalo Canyon Flora was collected by UCMP alum Daniel Axelrod years ago.1 The roads here were really bad — very rocky and heavily eroded — I was amazed that we continued to forge ahead, but somehow, all four of our vehicles made it through. We stopped at a great place to make camp, up on a ridge with wonderful views of layered exposures to the north and east.

I helped Mackenzie make a dinner of chili with bread and grated cheese. A campfire was made using dead sagebrush and juniper wood. We watched the sun set and the stars come out. Most everyone was in their tent by 10:30.

Tuesday, May 23

The day dawned clear — looked like we were in for another beautiful, but warm, day. After a breakfast of coffee, bagels and muffins, everyone packed up their gear. Then it was time to find those plant fossils.

Based on the dating of ash layers, the Buffalo Canyon Flora is considered to be about 15 million years old (middle Miocene). At that time, a large freshwater lake existed in this area, surrounded by lush vegetation. Today, the area gets about 15 inches of annual rainfall and most of that is snow; the dominant plant life includes pinyon pine, juniper and sagebrush. Axelrod, in comparing the fossil flora to modern analogs, believed that in the middle Miocene the area was receiving year-round rain, about 35 to 40 inches annually. He also determined that summer temperatures were cooler and winter temperatures were warmer than they are today. Fifteen million years ago the flora was a mixed conifer-deciduous forest with plants such as cattails and water lilies growing along the lakeshore. Axelrod identified over 50 different plant species in the diatomites, shales, and mudstones of the Buffalo Canyon Formation.

Neither Seth, Cindy nor Ivo had been to the Buffalo Canyon site before, so they were depending on directions given to them by UCMP’s Senior Museum Scientist in charge of the paleobotanical collections, Diane Erwin, who had been to Buffalo Canyon before. Diane identified the location of a good collecting area on Google Earth prior to our leaving Berkeley. We drove to the spot and began poking around on the hillside. We did find occasional leaves and seeds, as well as a few fish fossils, but Seth and Ivo were not convinced that we were in the best place. So they took one of the vehicles and disappeared for a while. They returned to report that they’d found a good layer at one end of a substantial quarry not too far away. After lunch we piled into the vehicles and followed Seth over some very dangerously eroded dirt tracks to the new spot. Seth pointed out the layer where we should look so the group spread out along an upper terrace of the quarry.

The leaves and seeds that we were finding were preserved as carbonized impressions in the diatomite. Sometimes the carbon would be leached away, leaving just the impression in the fine-grained rock. We found a great variety of leaves — primarily oak, elm, birch, sycamore, cattail, willow, as well as two water lilies and some winged seeds. After amassing a good number of specimens, the students were given an exercise in which they were to separate the leaf fossils by size and margin type; with these numbers, they were able to roughly calculate the mean annual temperature and precipitation at this location 15 million years ago. Despite having far fewer specimens than Axelrod (he collected some 6,000), the student’s numbers were not that much different from those of the paleobotanist.

Around 3:00 we left Buffalo Canyon and began the drive to Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. We followed a dirt track south down the canyon and over the pass at Buffalo Summit; at the top we caught a nice view of the Shoshone Mountains to the southeast, still with some snow on them in places. After coming down from the mountains (the Desatoyas), the road straightened out and ran southeast for about 15 miles across Smith Creek Valley. Along this route we saw a couple pronghorn, one being spotted just before reaching the ghost town of Berlin.

After a brief stop at the Berlin visitor center, a tiny wooden structure with nobody home, we continued on towards the campground. To our delight, we found signs saying that the entire campground was reserved for our group! At 4:45 we pulled up and parked right near the cabin that UCMP’s Charles Camp had built as his “home” back in the mid-1950s when he was spending long periods of time working at the ichthyosaur quarries.

We got out the coolers, food tubs, stoves, and cooking gear and Richard and Franzi started right in on preparing dinner, a tasty vegetable-rich curry. Around this time, Anthony, a park staffer, stopped by to make sure everything was okay and to remind us about our tour of the quarry scheduled for tomorrow. Seth asked if it would be possible to have our tour early in the morning and Anthony agreed to look into it. He returned a short time later saying that we could have our tour at 9:00. Daniel and Jun got some charcoal burning in the fire pit using toilet paper soaked in olive oil — worked like a charm. They grilled up some linguica sausage and corn on the cob to augment the curry. We dined at two picnic tables that we placed end to end.

I had been to the park a couple of times before, but had never checked out Camp’s cabin. In late 2014 I did a lot of research for the 2015 UCMP wall calendar entitled UCMP and the development of the ichthyosaur quarry at Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park. I’d read all of Camp’s field notes relating to this site and the building of the cabin so I found it very cool to be dining just a few feet from the cabin itself. I had brought a copy of the 2015 calendar with me to present to the park staff. Because of my knowledge of the site, Seth had me give our group a short talk about the park’s history.

After dinner we hung out at the picnic tables and kept the fire going with pine cones and some dead wood. Since we had the whole campground to ourselves, we were able to spread out our tents and get some privacy.

Wednesday, May 24

I got up as soon as it was light. I dressed and packed up all my gear, trying not to make too much noise. I took a walk along a path on the north side of the canyon; I didn’t know it at the time, but I walked right by one of Camp’s ichthyosaur quarries. When I got back to camp, Cindy and Ivo were busy preparing breakfast. Ivo fried up some potatoes to go with the usual breakfast fare. After the morning repast, we packed up the cars so that we’d be ready to go following our tour.

Just before 9:00 we hiked up the hill to the visitor center and were greeted by Mike, a retiree who’d be giving us the tour. A couple in an RV from the Sparks area tagged along with our group. Mike opened with some background info on ichthyosaurs and then told us about the bones exposed in the quarry before us.

The quarry protected by the A-frame shelter contains the partial skeletons of at least seven individuals of Shonisaurus popularis, Nevada’s State Fossil. The bones had a faint bluish cast to them making them easier to distinguish from the brown matrix. These ichthyosaurs swam in an inland sea about 220 million years ago. Camp could not account for why so many individuals ended up so close together. He theorized that the animals may have beached themselves and died, but current thinking is that the ichthyosaurs died in deep water, possibly from a toxic algal bloom. At the time of its discovery, these ichthyosaurs were the largest known, however, another species of Shonisaurus has since been found in Canada that is even larger (69 vs. 49 feet long). Almost 40 specimens — none of them complete — have been found in and around the park. Originally thought to have a dorsal fin like later ichthyosaurs, current reconstructions of Shonisaurus drop the fin because of its close affinity to the fin-less Shastasaurus.

After the tour, I gave Mike a copy of the UCMP Berlin-Ichthyosaur wall calendar and he said that he’d pass it along to his supervisor … after he’d read it. Mike told us about a couple other quarries that Camp had worked in; one was across the road from the campground (I had already visited it during my early morning walk). The other was back down the road a ways to the west, then south along a gully and up a ridge. The latter was a sizable quarry; Mike said that a National Geographic crew had done some excavating there recently. We found many bone fragments, as well as ammonites.

Here we thanked Mike for the informative tour, got back in our vehicles and left the park. We drove north on the dirt County Road 21, crossing over the Shoshones at Ione, then north again through the Reese River Valley towards 50. We finally hit pavement when we turned onto State Route 722. Seven miles later we hit 50 and headed east into Austin. In Austin we pulled into a Chevron market to get beverages and/or munchies.

Peter reported that he was getting a low-tire-pressure warning for his left rear tire. A screw was found embedded in the tire, so Peter moved the vehicle to a flat surface. We pulled out the owner’s manual and jack and figured out how to get the spare out from underneath the vehicle. Seth jacked up the Yukon, removed the bad tire and put on the temporary spare. The whole process took only a half hour. Then it was back on the road.

We stopped at the Hickison Petroglyph Recreation Area just past Hickison Summit for lunch. It was sunny, but very breezy and large thunderheads were visible off to the south and east. After eating we followed a trail to the petroglyphs. They weren’t too impressive, but then some had been damaged by vandals. We continued up the trail to get some great views. We saw many lizards, a snake, and a raven’s nest on a cliff face.

Back in the cars, we continued east towards Ely and didn’t bother to stop in Eureka. About 35 miles west of Ely, Richard and I began getting a low-tire-pressure warning. I reported this to Seth when we stopped at an exposure of the Carboniferous Ely Limestone just northeast of Illapah Creek Reservoir. The alternating thick and thin, gray limestones of the Ely exhibit cycles of marine sedimentation as sea levels changed during a period of worldwide climatic fluctuations. As one moves up in the sequence, the fossils change as you go from offshore to foreshore deposits and back again, providing a nice opportunity to examine how different groups track their favored environments. The fossils we observed included brachiopods, crinoids, rugose corals, bryozoans, and bivalves. Gastropods, crinoids, echinoid spines, and forams are also present in the Ely Limestone.

Our vehicle made it to Ely without any trouble. On the way there, we did have some short periods of rain but managed to dodge the more serious-looking thunderstorms. Seth had hoped that we could get Peter’s tire patched today, but we arrived too late (around 4:30) to have it dealt with; Peter took the Yukon to the tire shop — they said to come back in the morning at 8:00. While Peter was on his errand, the rest of us headed to the front desk of the Hotel Nevada and Gambling Hall, passing through its smoky casino on the way. Cindy checked us all in and distributed the card keys. After moving our gear into our rooms and cleaning ourselves up a bit (it had been over three days since our last shower), we returned to the lobby to rendezvous with the others. Our original plan had been to dine in the hotel’s restaurant, but it had been replaced by a Denny’s, so Cindy went online to look for better options. She found a place called the All Aboard Cafe & Inn where she was told that they had a table for all 11 of us. We drove over in three of the SUVs and were pleasantly surprised to find that we’d have a room of our own. The Inn had an excellent menu; dinners ordered included fried chicken, a ribeye steak, spaghetti and meatballs, and burgers. To our amazement, the waitress was happy to give us all separate checks. Back at the hotel, most everyone went to their rooms, but some, like Peter, went out again.

Thursday, May 25

Richard and I — we were sharing a room — were up around 6:30 since we were supposed to meet the rest of the group downstairs at 7:30. We packed up our stuff and took it out to the vehicle before heading to the lobby. When the group had all gathered (Mackenzie was missing but she would join us a little later), we walked across the street to The Cup for breakfast and coffee. When done, we returned to the hotel, checked out, and went to our vehicles. Peter left us to get his tire patched. Everyone else headed to the Ridley’s to get food and ice to last us through the end of the trip. While repacking the coolers, Peter returned and surprised us by turning over two six-packs of Great Basin Brewing’s Icky IPA; that’s what he had gone out to look for the previous night. What a good guy! From Ridley’s, we went to the Shell station across the street to top off our gas tanks and to put air in our traumatized tires. Continuing west on 50, we stopped briefly so people could take photos of the “antler gate” (an arched entry to someone’s property that’s made entirely of antlers).

Our original plan had been to visit the bristlecone pines in Great Basin National Park and to camp in the Park, but Seth had heard a weather report that called for cold temperatures; fearing that we might be unprepared for cold weather weather (and that the trail would be blocked by snow), he decided to skip the Park and head straight to Utah. We stayed on U.S. Route 6/50 and made a stop at the Border Inn (at the Nevada-Utah border, of course) to fill our water containers. We then entered Utah and Mountain Time (losing an hour). About 34 miles into Utah, we turned north onto Tule Valley Road, an unmarked dirt track that runs roughly north-south along the west side of the House Range. We made one stop to take photos of the dramatic western face of the range, dominated by the cliffs of Notch Peak, before turning east on the Old Route 6 & 50 Road and entering Marjum Canyon.

We stopped near the west end of the canyon, with high cliffs rising on each side, and got out to look at the Cambrian rocks. Seth pointed out large red masses in the rocks on the north side of the canyon. The red masses are infilled caves within the Howell Limestone, recording karsting and a drop in sea level during the Cambrian. On the south side of the road, Seth showed us gray limestones that were micrite (essentially massive carbonate mud), devoid of layering because of heavy bioturbation (mixing of the sediment by animal activity). In some places, orange patterns in the rock provided evidence of infilled burrows, created by arthropods and various worm-like creatures. Chunks of rock that had fallen from higher up on the cliff exhibited a sharp contact between the carbonate mud and an oncolitic rock. Oncoids are layered, spherical structures that form by the growth of cyanobacteria around a nucleus such as a piece of shell.

Continuing up the road, we made a second stop to look at trilobites and other fossils, including algae, in the Wheeler Shale; it too is of Middle Cambrian age but stratigraphically above the Howell Limestone. But first: lunch. During our lunch break, Erik Sperling, an Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences at Stanford and Richard’s advisor, drove up. He had flown into Salt Lake City a few hours earlier, rented a car, and somehow managed to find us.

Near the road, small agnostid trilobites, sponge spicules, and unidentifiable organic matter were found in the rocks of the Wheeler. These rocks were deposited in deep water where oxygen concentrations were variable. Higher up the hill the rocks were very laminated, indicating no bioturbation, a sign that oxygen levels were too low for most bottom-dwellers. However,the trilobite Elrathia kingi was quite plentiful. Apparently, it was well-adapted to the low-oxygen conditions. In fact, there are layers in the Wheeler Shales in which Elrathia occurs in dense accumulations, often 1,000 individuals per square meter.

When done with our trilobite hunt, we returned to the vehicles, left Marjum Canyon behind, and stayed on Death Canyon Road before turning southwest onto another dirt track, 3c Road, and took it back to 6/50. We drove west for a bit with the mostly dry Sevier Lake on our left before picking up Tule Valley Road again on the south side of the highway. We drove due south along a very dusty track, then turned west around the southern end of the Barn Hills. Seth steered us to a camping area at the base of Fossil Mountain in the Confusion Range. Only one couple with an RV and a little dog were camping there. The group fanned out to set up their tents while Peter and Emily set about making Peter’s jambalaya recipe for dinner. While looking around the camping area, Seth noted that arrowheads have been found here; seconds later Mackenzie bent down and picked one up! The jambalaya took a while to make so we ended up eating in the dark. Seth, Ivo, Franzi and others went off to collect wood for a fire. We sat up and talked to around 11:00. When I went off to find my tent in the darkness, I followed Daniel since his tent was on the same line from the vehicles as mine. The stars this evening were amazing.

Friday, May 26

I got up when it was too light to stay in my tent any longer. After a light breakfast, we prepared to leave camp but found that Seth’s Tahoe had a low-tire-pressure warning. The tire looked pretty low, so we left that one and drove off in the other three. Seth led us to a canyon in the House Range. The students split into groups of two or three to describe two-meter sections of the House Limestone. Seth urged the students to pay attention to details, such as ripple marks, burrows, and whether the carbonate rock could be described as a micrite or grainstone (a coarser limestone with grains that are cemented together). Following the exercise, the group discussed the possible depositional environments of the limestone. Based on the existence of ripple marks and fragmented fossils (trilobites, brachiopods, echinoderms), the carbonates were probably deposited in a near-shore, high-energy environment, probably between the fair weather and storm wave bases. Collared lizards, skinks and horned toads were also observed on this outing. On the way back to the cars, we made a side trip to a down-faulted chunk of the House Limestone to take a look at this stratigraphically higher piece. Above the House Limestone is the Fillmore Formation; Seth would have liked for us to look at that too, but the exposures were a bit hard to reach. So we skipped the Fillmore and drove across the valley to look at the Wah Wah Limestone, the next formation in the sequence. We had lunch by the cars before our walk up section, through the Wah Wah and into the Juab Limestone and Kanosh Shale.

The hillside before us presented a partial cross-section of what was once a thick carbonate platform built up in shallow water on a passive continental margin (i.e., there was no plate boundary in the vicinity). Numerous invertebrate fossils were present in these rocks, all the way to the top of the ridge. More than 60 years ago, geologist Lehi Hintze, who studied these Lower Ordovician rocks extensively, first measured this section and painted his measurements directly on the rocks. The measurements would have been erased by the elements long ago, but geologists periodically repaint them. Seth led us up the slope, following Hintze’s trail. We began by looking at the Wah Wah Limestone, a brownish-gray formation of mixed shales, micrites and grainstones. Again the students split into groups to describe two-meter sections. The Wah Wah was probably deposited at a depth similar to that of the House because of the presence of ripple marks, but there was a more diverse biota. In addition to silicified trilobites and echinoderms, there are also sponges with holdfasts, small sponge-microbial mounds, nautiloids, brachiopods, high-spired gastropods, and some graptolites in the shales.

Above the Wah Wah we moved into the Juab Limestone, generally similar to the Wah Wah, but a more medium to dark gray in color. It contained unsilicified trilobites, brachiopods, crinoid stems, and high-spired gastropods. Although the same major groups are present as in the Wah Wah, Seth pointed out a sharp shift in faunal dominance —whereas the Wah Wah is numerically dominated by trilobites, the Juab is dominated by brachiopods. This ecological shift occurs gradually in many places during the Lower-Middle Ordovician, but in this area it is particularly striking and abrupt.

Overlying the Juab Limestone is the Kanosh Shale, which records a local increase in water depth. The Kanosh is composed of a variable mixture of shales and limestones, but we found the shales to be obscured by soil and rubble. The limestones are often very fossiliferous, and in the rock-strewn surface there were abundant brachiopods, gastropods, trilobites, ostracodes, nautiloids, echinoderms, and more.

Since it was getting close to 5:00, we climbed back down to the vehicles and returned to camp. It had become quite windy. Seth attempted to fix his bad tire with Fix-a-Flat but it had no visible effect. While he was out doing that, Eric, Richard, Emily and Franzi hiked over to the cliffs northwest of camp to have a look at the upper Kanosh Formation. Seth’s spare also turned out to be low on air, so he would have to go into Ely tomorrow to get the tires serviced. Everyone but Seth, Emily, Franzi and Richard would be returning to the Bay Area the next day so Seth would caravan with us as far as Ely.

For dinner, Cindy and Ivo made a big pasta dish with a sauce containing eggplant and olives; I assisted by peeling some garlic. I went out to gather wood for a fire but didn’t find much. I’d been told that Seth would want to keep the Expedition that I’d been driving so I removed all my stuff from the back and moved it to my tent. It remained very windy and became overcast — we tried to position the vehicles so that they’d provide some shelter. We all headed to bed before 10:00. Shortly after getting to my tent, it began to drizzle and was still drizzling when I turned out my light.

Saturday, May 27

The plan was to hit the road by 6:00 today so the night before I had asked Daniel to wake me when it was 5:00. I had expected it to be light out at that time, but when Daniel came to wake me, it was still dark. I packed up, brought all my stuff over to the vehicles, and had a very light breakfast.

It wasn’t until 6:30 that we finally got underway. Seth, with Richard, Franzi, and Emily, led the way to Ely in the SUV with the nearly-flat tire. It turned out that Seth would not be wanting my Expedition after all, so with Peter and Daniel as passengers, we made to leave camp when — wouldn’t you know — our low-tire-pressure warning light came on again. We ignored it. Cindy, Ivo, Mackenzie and Jun were in another SUV. The fourth vehicle would remain at Fossil Mountain since Seth would be needing two vehicles to get his three passengers, all their gear, and all the food bins, coolers, etc. back to Berkeley. At the Border Inn, we found air, so both Seth and I filled our tires. We made it to Ely without incident, meeting up at the Shell station to top off our gas tanks. We said our goodbyes to Seth and the three students remaining with him — they were staying a few days longer to do some field research in the area — and began the long drive back to the Bay Area. We made a few stops for gas and food along the way; I was back at my house in Berkeley by 6:00 PM.

And thus ended the 2017 UCMP field trip! It was not so much about the origins of the Basin & Range itself, but about some of the individual rock formations and what their rocks and fossils tell us about what was going on in terms of changing sea levels, oxygen and carbonates in the oceans, and climate.

Cal Day 2017 at UCMP

On April 22, 2017, the UCMP and Berkeley Natural History Museums provided another outstanding day of fun scientific and educational activities on Cal Day, the annual campus open house. Departments invite prospective students and the greater Berkeley community to explore new and exciting research on campus. It also provides the public and friends of UCMP the opportunity to become Junior paleontologists, see rare fossils and take special tours to check out the inner workings of the UCMP, not normally open to the public.

Our 2017 t-shirts featured a block out style T. rex and Kossmatia, an ancient ammonite from our collections, illustrated by our very own David K. Smith (get yours here).

The crowds of visitors multiplied exponentially as the day went on. Families enjoyed the activities on display by the BNHM in the Valley Life Sciences courtyard on the second floor. From a live mini kelp forest, to stick bugs, to our Proboscidean fossils, the BNHM offered everyone a peek into the variety of science disciplines here on campus. Our younger friends enjoyed an afternoon of digging for fossils at our Fun with Fossils activity.

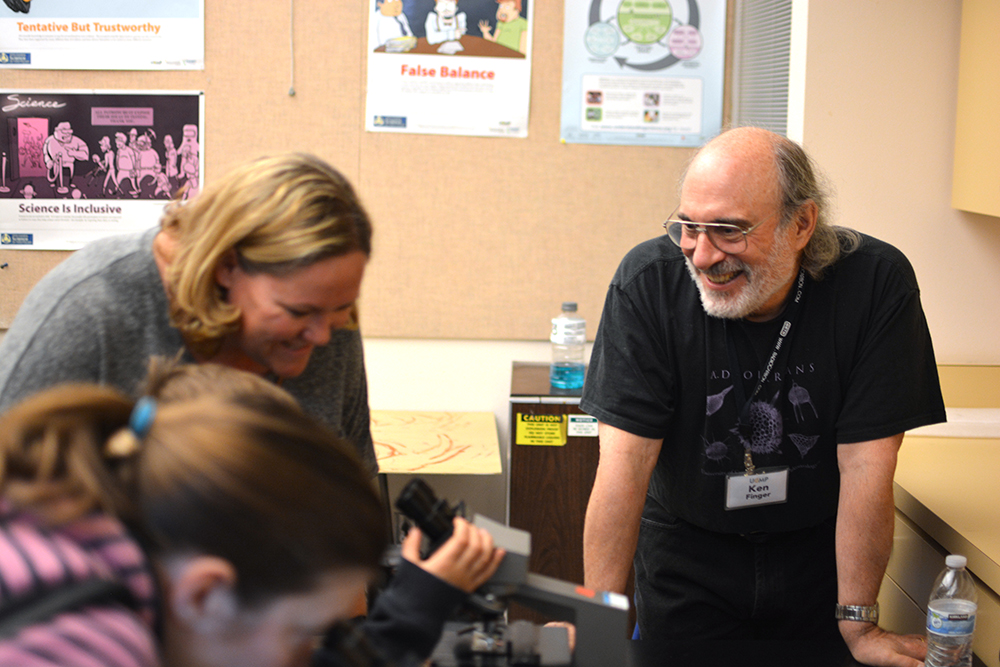

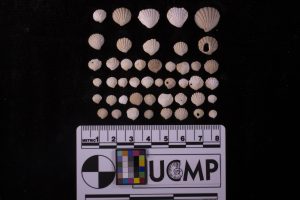

This year, UCMP was determined to show that the paleontological sciences are more alive than ever! The theme for the UCMP was Fascinating Fossils! Charismatic specimens representing the different parts of our collections were on display. These included horned dinosaurs, antlers from ice age megafauna, and even tiny microfossils. Professor Emeritus Bill Clemens, pictured above with a large pachycephalosaur, spent the day inspiring young visitors. Along with many of the UCMP graduate student volunteers, Bill described how paleontologists at UCMP study the fossils in our collections while drawing connections between the fossils and the larger environmental implications. Ken Finger featured microfossils and visitors excitedly examined their elegant symmetry under the microscopes.

Even our Director Charles Marshall joined in the fun, donning a pair of Megaloceros antlers at the Selfie Station. All in all, it was another successful Cal Day.

What's new in the collections

UCMP is now two years into a large-scale digitization project focused on fossil marine invertebrates from the eastern Pacific: EPICC. Led by Museum Scientist Erica Clites and Staff Assistant Lillian Pearson, a group of 14 undergraduate students and 4 graduate students (Peter Kloess, Mackenzie Kirchner-Smith, Nick Spano, Susan Tremblay) have cataloged 21,000+ fossil specimens, georeferenced nearly 4000 localities and taken 700+ photographs. Together with our eight museum collaborators listed on epicctcn.org the EPICC Thematic Collections Network has completed 42% of our specimen digitization, 26% of our specimen photography and 38% of our locality georeferencing. Five museum partners are serving data to biodiversity aggregators such as GBIF and iDigBio.

The results of this project will be 1.6 million invertebrate specimen records that can be used to study faunal responses to environmental change over 66 million years of Earth’s history along the longest continuous coastline in the world.

We have published several guides on our website, including a guide to labeling marine invertebrate fossils and a guide to photographing marine invertebrates. The EPICC project also involves several UCMP/UC Berkeley alumni, including Liz Nesbitt(Burke Museum, University of Washington), Edward Davis (University of Oregon) and Jann Vendetti (Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County).

We are very close to launching the first set of EPICC Virtual Field Experience modules, which will reconnect fossil specimens with the field localities where they were collected. Lisa White and colleagues at the Paleontological Research Institution are leading this effort. The modules include video footage, Gigapan macro images, photographs of outcrops and other rich sources of data to guide inquiry.

UCB alum Wayne Thompson, now a science teacher in Los Gatos, has been scouting the Santa Cruz County cliffs since the 1980s and made a number of interesting discoveries. The most recent discovery is a walrus ankle bone (astragalus) from the Purisima Formation near Capitola, which Wayne generously donated to UCMP. After some preparation, it became obvious that the bone belongs to the walrus Valenictus – an extinct walrus that had extremely dense bones. Based on skeletons from the San Diego Formation, Valenictus was “toothless” – lacking all of its teeth aside from the enlarged tusks. Two possible skulls of Valenictus from the Purisima Formation may further represent this species, but require further preparation and study. Wayne’s fossil is the first confirmable record of the toothless walrus from Northern California and the first from the Purisima Formation, the fossil assemblage which UCMP Research Associate Bobby Boessenecker is documenting. Pliocene marine rocks from California and Baja California have yielded a bizarre fauna including temperate belugas, long snouted ‘river dolphins’, proto-gray whales, giant sea cows, a more diverse porpoise fauna including bizarre benthic feeding species, dwarf benthic feeding baleen whales, double-tusked walruses, and of course, Valenictus. This fauna is quite different from modern counterparts, indicating a non-trivial degree of faunal change during the Plio-Pleistocene.

Staff Updates

McKittrick Project

With funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS), the UCMP recently completed rehousing the largely vertebrate fossil collection from the McKittrick tar seeps of the Central Valley. Most of the collections were made during UCMP excavations between 1921 and 1927, with additional collections in the mid-1940s by John C. Merriam. The fossils were mostly stored in the Campanile bell tower and lay uncatalogued for more than 75 years.

Over the past two years, more than 13,000 specimens from the McKittrick collection have been identified, cataloged, and digitized by Pat Holroyd, with a team of student assistants working under her supervision. This collection, of special value to California – the McKittrick site near Bakersfield is a historical landmark – is now the subject of a series of education modules that will soon be available on the UCMP website. The materials will offer a variety of interactive experiences for young audiences including a McKittrick-area site reconstruction, an interactive Pleistocene food web, and the “Great McKittrick Fossil Find” – an anatomical puzzle challenge using authentic fossils from the site.

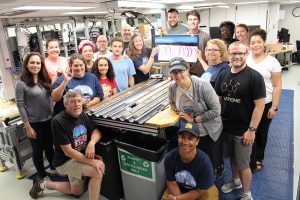

School of Rock

What do you call 20 educators from 6 states, 3 countries, sailing for 17 days in the Pacific Ocean from the Philippine Sea to the Great Barrier Reef? An International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) School of Rock expedition! Lisa White was part of a team of instructors co-leading an oceanography workshop onboard a unique floating laboratory, the JOIDES/Resolution (JR). Designed to recover sedimentary cores from water depths as deep as 4 miles, results from the ship’s scientific expeditions have contributed much of what we know about the deep time record of the oceans.

For these reasons the ship was an ideal venue to host the unique training and professional development workshop aimed specifically at scientists and secondary educators from communities that remain poorly represented in the geosciences. During the 17 day transit, pairs of early career scientists and high school earth science teachers were introduced to cutting edge ocean science, pedagogical tools, and mentoring strategies for diverse high school and undergraduate audiences. Lisa is a veteran of several IODP cruises, having sailed previously on the JR as a shipboard scientist/diatom micropaleontologist. With opportunities available to teachers to experience first-hand the science capabilities on the ship, communicating science is even more authentic.

iDigBio Workshop at UC Berkeley

The generation, mobilization, and research use of digital data in the biodiversity sciences is continuing to increase at a rapid pace. This is especially true for paleontology. Within the last half decade of NSF ADBC (Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections) funding, paleo-related Thematic Collections Network projects have been awarded during four of the six annual award cycles. These collaborations have spurred intense activity in the paleontological community, led to the establishment of the iDigBio Paleo Data and Digitization Working Group, fostered several TCN and iDigBio-sponsored paleo-focused digitization workshops, engendered high levels of community participation, and resulted in an important focus on the uses of digital data in paleontological research.

On March 26-27, 2017 about 60 vertebrate and invertebrate paleontologists, including faculty curators, collections managers, informatics professionals, and approximately 15 graduate students gathered at the UCMP in Berkeley for iDigBio’s fourth paleo-related workshop. Dubbed “Digital Data in Paleontological Research” the workshop’s primary goal was to carry participants beyond digitization and into methods and issues in using the digital data that the community is producing. Visit iDigbio Digital Data in Paleontological Research for more information.

See-Through Dinosaur Skull

UCMP participated in the Berkeley Crowdfunding Initiative earlier this year in February.

UCMP participated in the Berkeley Crowdfunding Initiative earlier this year in February.

Our See-Through Dinosaur Skull project received enough funding to perform the CT scan, the most important part of the research project!

Thanks again and Shout-Out to the following donors for their support!

Elaine Bernal

Thibaut Brunet

Helina Chin

Douglas Clarke

William Clemens

Erica Clites

Mark Goodwin

Patricia Holroyd

Eric Holt

Randall Irmis

Rebecca Jabbour

Natasha Johnson

Uwe Krause

Teresa Lau

Constance Milbrath

Jason Schein

Tammy Spath

Carol Spencer

Allison Stegner

Linda Thanukos

Gretchen Trupiano

Sarah Tulga

Lisa White

Gregory Wilson

Friends of UCMP

We would like to welcome the following new or renewing members to our Friends of the UCMP

Benefactor

Marc * & Linda Currasco

William Clemens *

Douglas Dreger

Everett H. Lindsay *

Stephen & Barbara Morris

Kevin Padian

Judy Scotchmoor* and Roland Gangloff*

Sponsor

Roland Burgman

Carole Hickman

Seth Finnegan

Pat Holroyd

Mehdi Mohtashemi *

Paul Renne *

Patron

Daria M. * & Jay J. Ague *

Paul Babwin *

Philip Englander

Sean Ford

Lynn Gotchall

Sue Hoey

Michael Manga

Paul David Polly *

Julia Sankey

Doris Sloan *

Nicholas Swanson-Hysell

Hugh Wagner *

Mark G. & Judy Yudof

Sustaining

Roseanne Chambers *

Dennis T. Fenwick

David Johnson

John Mawby *

Mary Ann McCall *

Steven Rocchi *

Donor

Jim Bonsey

Alice T. Taylor & Taylor A. Schreiner

Susumu Tomiya *

- * alumni