Continued from page 1

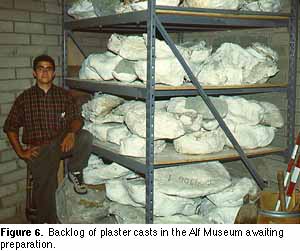

STUDENTS AS MUSEUM SCIENTISTSDONALD L. LOFGRENCARE OF FOSSILSWhen a fossil is first obtained by the Alf Museum, it is usually placed in temporary storage. Then the fossil will undergo a series of steps that ensures its scientific value will be maximized before it is curated into the permanent collections of the museum.Temporary Storage — Rarely are specimens immediately placed into the permanent collections when they first arrive. They are usually placed into temporary storage where they may reside for as little as a few days, to as much as many years. This time disparity is the result of labor constraints and the differential importance of specimens. Specimens that are unique or are critical to ongoing research efforts have priority and are sent to the preparation room first to be readied (removed from rock, cleaned, repaired) for museum use. Specimens deemed less important may await preparation indefinitely. The amount of time it takes to collect fossils, especially vertebrates, is far less than it takes to prepare them. For a typical vertebrate fossil that was collected by using burlap and plaster to encase the specimen, it takes ten to twenty times as long to prepare the specimen as it did to collect it. Thus, if a museum has an active field program, many hundreds of hours of labor in the preparation lab are required to keep abreast of the annual influx of specimens. Most museums cannot afford to retain the number of preparators required to keep up with fieldwork and a backlog of specimens awaiting preparation builds. At the Alf Museum, the backlog is small, but a few specimens await preparation that were collected over forty years ago (Figure 6).

Most museums have difficulty getting fossils prepared. Fortunately, the Alf Museum has a

large supply of student labor available. Students work as volunteers preparing fossils after

school and students in Museum Studies are assigned preparation work during class time and

as homework. Thus, the Alf Museum is able to maintain a steady supply of prepared

specimens ready for inclusion into the permanent collections.

Curation — Once specimens are ready to be placed into the permanent collections of the Alf Museum, they must be curated. Curation is defined as the process of documenting and organizing the collections. Collections documentation is a critical part of curation and can be divided into three parts as follows:

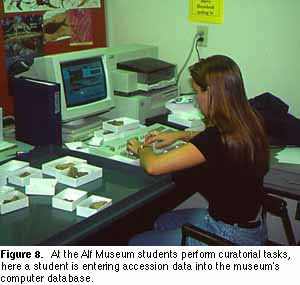

At the Alf Museum, Museum Studies students are very helpful because they learn how to

enter accession and locality data into the computer, and thus function as curatorial staff (Figure 8). However, students are rarely able to catalogue fossils without close supervision, because few students have the extensive experience in anatomy, taxonomy, and paleontology necessary to correctly identify most fossils.

USE OF FOSSILSA common misconception about museums is that specimens not on exhibit are just useless fossils gathering dust in some dark backroom of the museum. Many times donors visit and are puzzled and dismayed that the fossils they gave to the museum are not on display. They see little benefit from their donation unless the specimens are on exhibit. However, besides displays, specimens at the Alf Museum are used in teaching science courses at The Webb Schools and in research conducted by Alf Museum staff and students. The museum also loans specimens to paleontologists from other institutions who use them for research or exhibit. Again, the collections of the Alf Museum function as a "library of fossils", where specimens are used in a variety of ways. Return to top Return to top

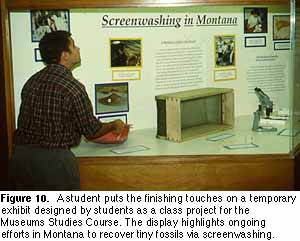

Exhibit — Exhibits are a way for museums to educate the public, highlight the importance of their collections, describe current research activities of staff, or "show off" interesting or visually appealing specimens. Exhibits should be designed to attract visitors so the information being presented is assimilated. Displays often are designed so that one exhibit builds upon information given in the one that proceeded it, so a general theme is developed over the course of many exhibits. Commonly, an entire exhibit hall has a theme. Displays are comprised of a number of different components which include: the specimens themselves, explanatory text, lighting, a structure to house the specimens, photos and/or graphics, and other components. Text is a critical factor because exhibits need to be understood to be effective. A display should not be too complicated or technical in its presentation of information. Displays that convey too much information or have a multitude of unfamiliar scientific terminology will be quickly bypassed by most museum visitors. Students in Museum Studies are required to critically analyze displays in the two exhibit halls of the Alf Museum. After they have critiqued displays developed by others, students design their own displays. They soon learn that designing an effective display is more difficult than it appears. The Alf Museum also has a temporary exhibit program where students design and construct displays based on current museum research efforts (Figure 10). These temporary exhibits are redone on an annual basis by each successive class of Museum Studies students.

Research — Perhaps the most important use of the collections is research.

Paleontologists study fossils and publish the results of their research which becomes a matter of record in the paleontological literature in perpetuity. Thus, research must be completed in a very careful and thorough manner. At the Alf Museum, as with most museums, staff conduct research based on specimens in the collections. The number and quality of research papers produced by staff add to the stature of the museum. Also, the importance and stature of the collections is based partly on how often specimens in the collections are referred to in published works. Finally, paleontologists often visit other museums to study their collections. Museums with large permanent collections, such as the University of California Museum of Paleontology, have dozens of paleontologists visit annually. Smaller museums, with collections of modest size, like the Alf Museum, have far fewer. Staff introduce students in Museum Studies to research by having them read and critique a number of journal articles (Figure 11). Later, students are required to complete a research project using specimens in the collections as well as the paleontological literature. Students report the results of their work orally in class and also write a research paper in the format of a journal article.

CONCLUSIONStudents in the Museum Studies course at The Webb Schools of California have the unique opportunity to learn how to function as museum scientists working in a paleontology museum. Using the facilities of The Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology, students are instructed in various museum activities, from how to collect fossils so they retain their maximum scientific value, to how the permanent collections are organized so that fossils can be retrieved for use in education, research, exhibit, and loan. Students who excel in the Museum Studies course are well prepared to volunteer or perhaps even seek employment at other types of natural history museums. But more importantly, students leave the course with a deeper understanding of the mission of the Alf Museum and how the museum serves both the general public and the scientific community.

|

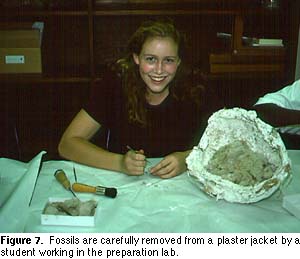

Preparation — As mentioned above, preparation of fossils can be very time

consuming. Tiny fossils collected using screenwashing techniques are separated from the

rock using a microscope and are placed in glass vials for safe storage. This sorting of fossils

requires a sharp eye and many hours of work. Vertebrate and plant fossils brought in from the

field commonly require cleaning and repair if collected as float. Vertebrate specimens

collected using burlap and plaster need to be removed from the encasing rock (Figure 7) and treated with chemicals to stabilize them. Invertebrate fossils usually require little preparation other than a simple cleaning.

Preparation — As mentioned above, preparation of fossils can be very time

consuming. Tiny fossils collected using screenwashing techniques are separated from the

rock using a microscope and are placed in glass vials for safe storage. This sorting of fossils

requires a sharp eye and many hours of work. Vertebrate and plant fossils brought in from the

field commonly require cleaning and repair if collected as float. Vertebrate specimens

collected using burlap and plaster need to be removed from the encasing rock (Figure 7) and treated with chemicals to stabilize them. Invertebrate fossils usually require little preparation other than a simple cleaning.

Locality Records — Where was the specimen collected? Before it can be stored in the collections, each specimen needs to be assigned to a specific site which is denoted by a

unique locality number. Locality numbers consist of five digits preceded by a V, P, or I,

which denotes that the site produces fossil vertebrates, plants, or invertebrates,

respectively.

Locality Records — Where was the specimen collected? Before it can be stored in the collections, each specimen needs to be assigned to a specific site which is denoted by a

unique locality number. Locality numbers consist of five digits preceded by a V, P, or I,

which denotes that the site produces fossil vertebrates, plants, or invertebrates,

respectively.

Permanent Storage — A museum is basically a "library of fossils", in which fossils are preserved and stored for the public good. Part of the mission of the Alf Museum, or any museum, is to store specimens within an organized system where fossils (and associated field data) can be retrieved when needed (Figure 9). Specimens are organized at the Alf Museum using four main criteria in the following descending order: (1) Geologic Age (a subdivision of the geologic time scale corresponding to the age of the fossils); (2) General Geographic Location (country, state/province); (3) Rock Formation (rock unit from which the fossils were collected); (4) Specific Location (specific site information, both geologic and geographic; each site is assigned a unique number). The four criteria should be present in field notes (if the specimen is procured by collection) or the accession record (if the specimen is obtained by donation or purchase). These criteria are included in the catalogue record of every

specimen. Thus, a dinosaur fossil from the Bug Creek Anthills site of eastern Montana would

be stored by geologic age-Late Cretaceous; then general geographic location-United States,

Montana; followed by rock formation-Hell Creek Formation; and then by specific location-

Bug Creek Anthills-V94046 (Alf Museum locality number). Using this or any other

organizational system, a museum has its collections organized like a library, where fossils

can be easily located for use in exhibit, research, or education (teaching), as well as for loan

to other institutions.

Permanent Storage — A museum is basically a "library of fossils", in which fossils are preserved and stored for the public good. Part of the mission of the Alf Museum, or any museum, is to store specimens within an organized system where fossils (and associated field data) can be retrieved when needed (Figure 9). Specimens are organized at the Alf Museum using four main criteria in the following descending order: (1) Geologic Age (a subdivision of the geologic time scale corresponding to the age of the fossils); (2) General Geographic Location (country, state/province); (3) Rock Formation (rock unit from which the fossils were collected); (4) Specific Location (specific site information, both geologic and geographic; each site is assigned a unique number). The four criteria should be present in field notes (if the specimen is procured by collection) or the accession record (if the specimen is obtained by donation or purchase). These criteria are included in the catalogue record of every

specimen. Thus, a dinosaur fossil from the Bug Creek Anthills site of eastern Montana would

be stored by geologic age-Late Cretaceous; then general geographic location-United States,

Montana; followed by rock formation-Hell Creek Formation; and then by specific location-

Bug Creek Anthills-V94046 (Alf Museum locality number). Using this or any other

organizational system, a museum has its collections organized like a library, where fossils

can be easily located for use in exhibit, research, or education (teaching), as well as for loan

to other institutions.

Teaching — Similar to the relationship of the Alf Museum with The Webb Schools,

museums associated with educational institutions provide and maintain teaching collections

for use in science courses. Specimens used in teaching are usually stored directly in the

classrooms themselves so they need not be moved back and forth from the classroom to

collections storage rooms after each academic session. The teaching collections at the Alf

Museum consist of rocks, minerals, and fossils used in an introductory paleontology and

geology course taught by museum staff. Museum Studies students work directly with the

permanent collections.

Teaching — Similar to the relationship of the Alf Museum with The Webb Schools,

museums associated with educational institutions provide and maintain teaching collections

for use in science courses. Specimens used in teaching are usually stored directly in the

classrooms themselves so they need not be moved back and forth from the classroom to

collections storage rooms after each academic session. The teaching collections at the Alf

Museum consist of rocks, minerals, and fossils used in an introductory paleontology and

geology course taught by museum staff. Museum Studies students work directly with the

permanent collections.

Loans — Museums, like the Alf Museum, make specimens in their permanent

collections available for use by other institutions through loans. Requests for loans are

usually granted. A measure of the importance of a museum's collections is how often

specimens are requested for loan. Specimens loaned to other institutions may be used for

exhibit, but are more commonly used for research. Museums usually loan specimens for a

period of up to one year and most loans are returned promptly. However, once specimens

leave the premises, the lending institution has limited power to enforce the loan deadline and

specimens can be on loan for a dozen years or more.

Loans — Museums, like the Alf Museum, make specimens in their permanent

collections available for use by other institutions through loans. Requests for loans are

usually granted. A measure of the importance of a museum's collections is how often

specimens are requested for loan. Specimens loaned to other institutions may be used for

exhibit, but are more commonly used for research. Museums usually loan specimens for a

period of up to one year and most loans are returned promptly. However, once specimens

leave the premises, the lending institution has limited power to enforce the loan deadline and

specimens can be on loan for a dozen years or more.