by Dave Smith; all color photos by Dave Smith

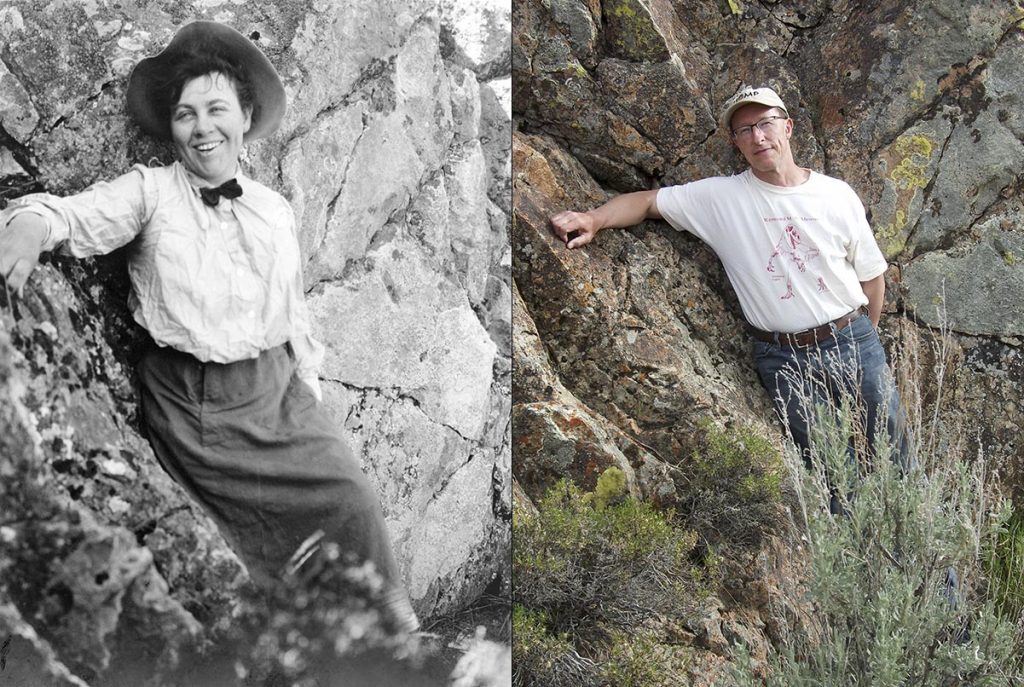

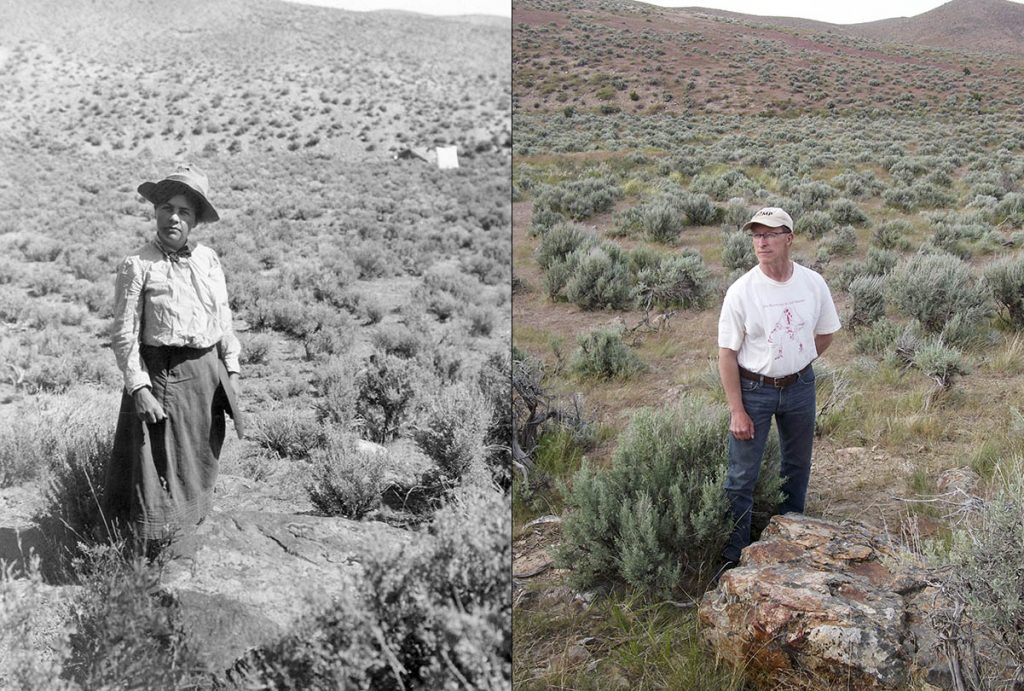

In 1905, an expedition from the University of California’s Department of Geology in Berkeley spent almost two months in the West Humboldt Mountains of Nevada collecting ichthyosaur fossils. Annie Alexander, the woman to whom UCMP owes its existence, was a participant in that expedition. She probably kept a journal or took field notes; following the trip, she put together a scrapbook containing typed pages of text and numerous photographs (mostly hers, but some of John C. Merriam‘s as well) and at some point gave it to the museum. This scrapbook is one of the most cherished items in UCMP’s archives.

The first members of the expedition to arrive at their destination in the West Humboldts were Annie, her friend and fellow paleontology student Edna Wemple, and the expedition leader Eustace Furlong. They were joined a few days later by Professor Merriam and two students, William Boynton and Malcolm Goddard. Professor James Perrin Smith of Stanford University participated for a week but his interest was in ammonites, not ichthyosaurs.

Kirk Hastings, a friend of mine who works at the California Digital Library in Oakland (CDL is a unit within the UC Office of the President), had suggested that the two of us do some hiking in Nevada and that got me to thinking. It would be fun to return to the West Humboldt Mountains and attempt to relocate some of the quarries worked by Annie and the Berkeley crew so I pitched the idea to Kirk. He liked the idea so I had 5×7 prints made of several of the photographs from Annie’s scrapbook; I thought that these would be helpful. I also printed out a copy of the scrapbook pdf.

On May 8 — exactly 112 years to the day after Annie arrived in the West Humboldt Mountains — Kirk and I left Berkeley for Nevada. I had located the canyon — South American Canyon — where the Berkeley crew had been based, but I had not been able to establish whether the ichthyosaur localities were on public or private land, so Kirk and I made our first stop the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) office in Winnemucca. They were able to tell us that the land was indeed privately owned but they could not remember the name of the owner. They advised us to backtrack to Lovelock and visit the county assessor’s office there — we would be able to find the name of the owner and perhaps some contact information. So we followed that advice and obtained the name of the land owner, one Patrick Embree. Unfortunately, the assessor’s office only had a mailing address for him — no phone number — so I pulled out my phone and did a Google search. Several phone numbers popped up but none of them seemed particularly reliable. Still, I selected one that appeared more than once and dialed it. I reached an answering machine and left a message identifying myself and my intentions and asked that I be called back. We realized that the chances of my dialing both the correct number and my getting a return call were slim to none, but about five minutes later, my phone rang. It was Patrick! Like me, he too was interested in retracing Annie’s steps in the canyon and was well aware of her scrapbook — in fact, he had at one point spoken with Mark Goodwin about it, offering to pay the museum to have the scrapbook scanned. Patrick was also interested in continuing Annie’s legacy of locating and excavating Triassic marine reptiles and he’s had some success in that area.1 I think he was genuinely pleased to see someone from UCMP taking an interest in the 1905 expedition and said that Kirk and I were welcome to camp on his land and look around all we wanted. Patrick even invited us to stay at his preferred camping area — a clearing with one large juniper tree and a picnic table — that he said was just a short walk from the old cabin where the Berkeley crew had camped. This was an incredible stroke of good luck. Without Patrick’s permission to camp and roam freely about his land, our mission would have been doomed.

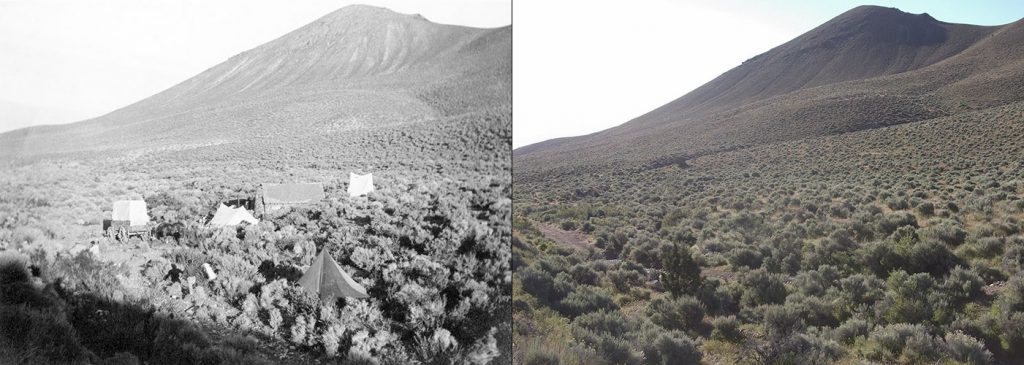

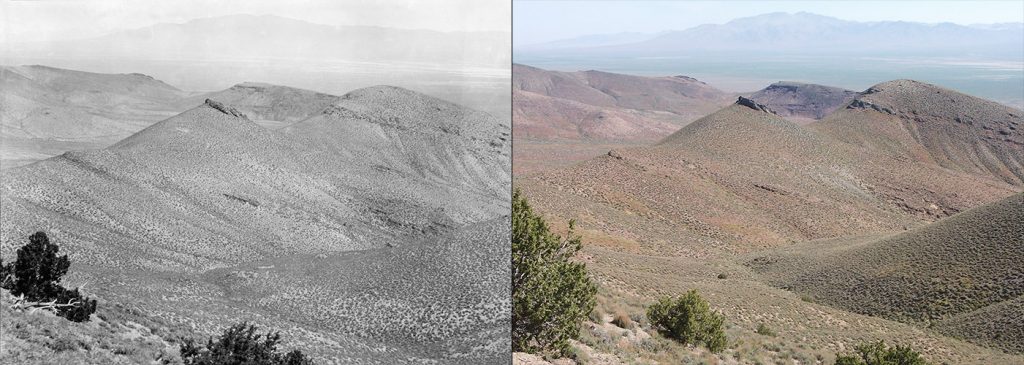

We spent the night of the 8th in Winnemucca but relocated to the camping spot in South American Canyon on the 9th. As we approached the canyon from the north on the unpaved Buena Vista Valley Road, I recognized what Annie called Saurian Hill immediately based on its distinctive sharp peak and the pattern of junipers on its northeast flank. Even after 112 years, many of the same junipers were still going strong. We needed our phones to map our route into the canyon because none of the roads out here are signed. We also needed Kirk’s four-wheel drive, high-clearance truck — such a vehicle is necessary to navigate what pass for roads in these canyons. But we made it to the camping area (clearly visible in Google Maps satellite view) and couldn’t have asked for a nicer spot. The views in all directions were beautiful and, with the exception of a solitary shepherd, we were the only humans in the canyon.

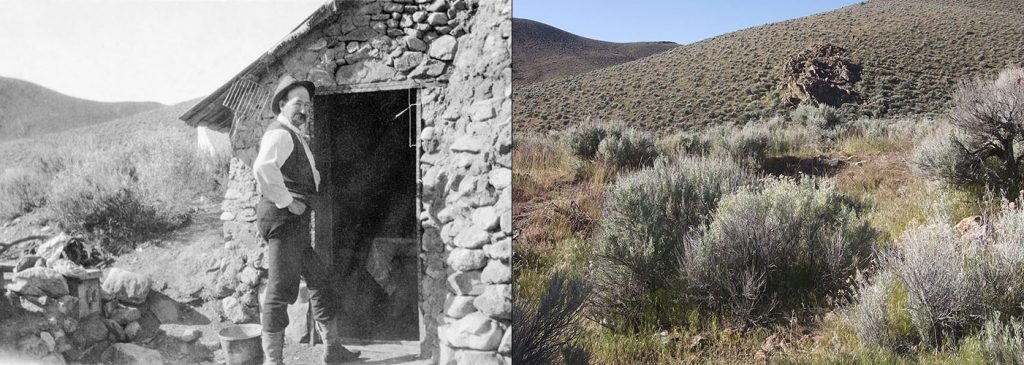

The ruins of the cabin where Annie et al. camped — now just a shallow excavation and some rock rubble — were about 70 yards NNW of us at a point where the road is crossed by a spring-fed creek. From the photographs that Annie took, you couldn’t tell that there was a creek just a few feet from the cabin so it came as a surprise to me that this was the case. I was to examine the cabin location a couple of times during our stay but the quarries were my priority, so on our first full day in the canyon, we climbed up the north flank of Saurian Hill.

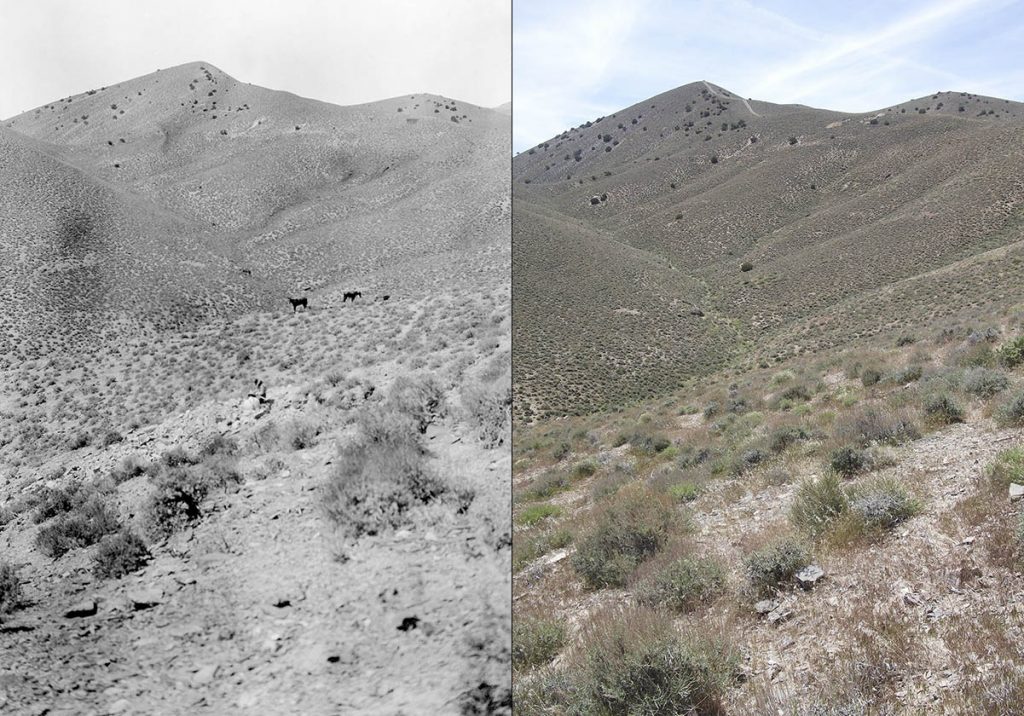

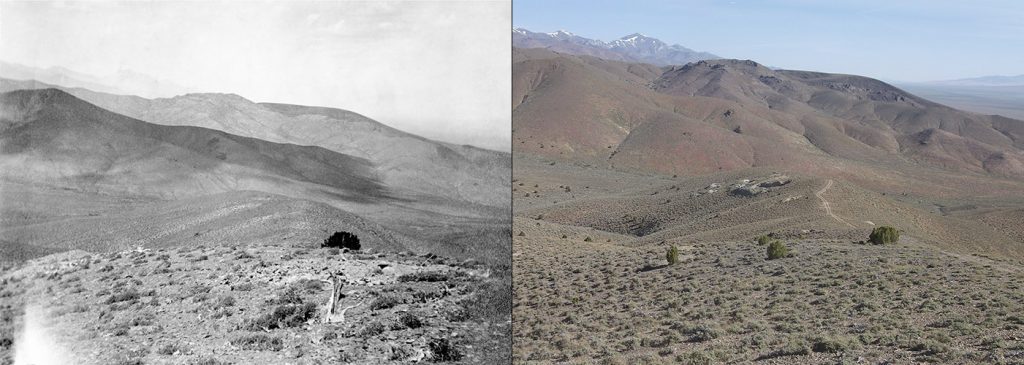

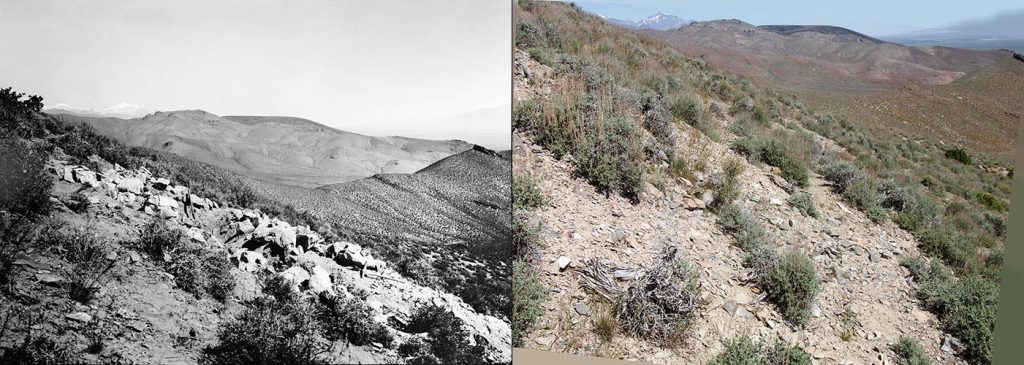

Armed with my 5×7 prints, we were able to relocate (with some degree of certainty) two of four quarries on Saurian Hill’s north slope, two on its east slope, and two — the ones Annie referred to as “The Gorge” and “The Tunnel” — on the south slope of Fossil Hill. Not bad for our first day! Excavations were still evident for the first and last pairs, but the quarries on the east slope of Saurian Hill were so shallow that no sign of them remains today. Yet in all cases, I was able to orient myself such that the background hills matched those in Annie’s and Merriam’s photographs; I felt confident that I was standing close to where they were standing when they photographed the quarries. As I noted earlier, a good many of the junipers pictured in the photographs are still alive today. The same cannot be said about the sagebrush and other shrubby plants; they apparently have much shorter lifespans.

On the morning of our second day in the canyon, I made my first examination of the cabin area. In the photographs, I had not noticed that the foundation of the cabin had been dug into the slope but I was glad that it had been. If not for that shallow excavation, it would have been hard to say whether this was the location of the cabin or not. Most of the rocks that were used to construct it had either been washed away, buried or carried off to be used elsewhere — there really aren’t many remaining today.

Then it was back up Saurian Hill. This time we went around to its southwest flank where Annie reported that there were nine quarries. Unfortunately, she took no photographs of these quarries (if she did, I didn’t recognize them as such) so I was unable to establish their locations. In fact, I only found a single excavation that might have been one of their quarries. From here, Kirk and I returned to “The Gorge” and “The Tunnel” quarries near the base of Fossil Hill’s south slope because the day before I had noticed that there were many ammonite fossils lying in the rubble. It was these ammonites that lured Stanford professor James Perrin Smith out here in 1905 to join Annie and the others for a week. He spent that week collecting ammonite fossils on this very slope. Kirk and I did not collect but spent a fair bit of time here admiring them. Although they’re particularly numerous on this slope, we found ammonites throughout the Triassic limestones in this area.

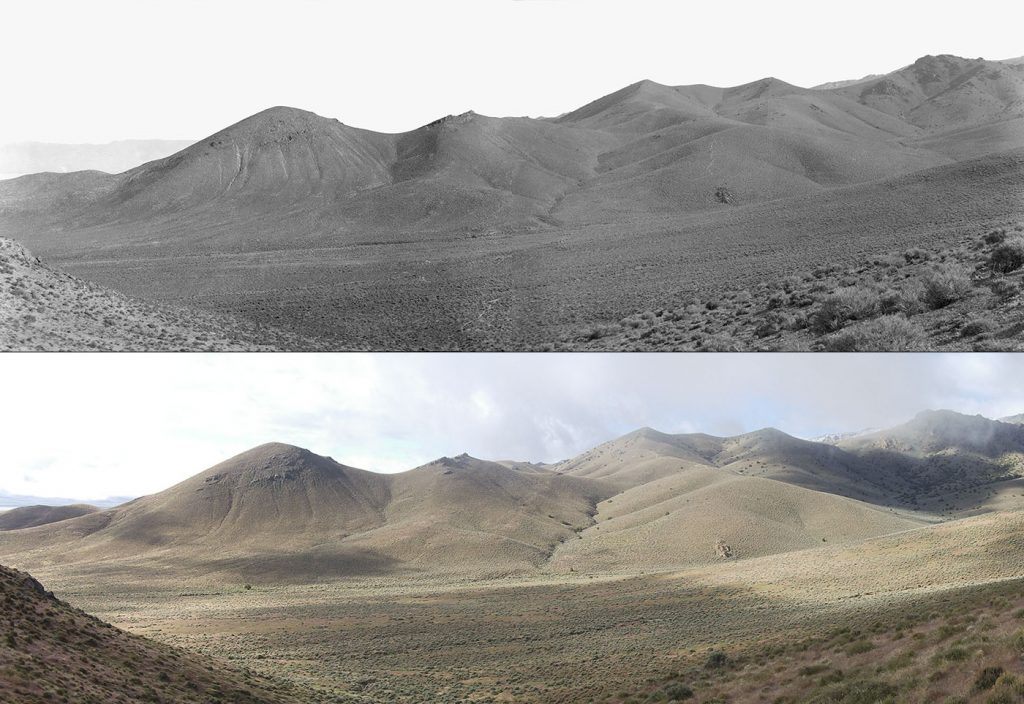

The next morning Kirk set out to hike up to Buffalo Mountain, an estimated 15-mile round trip. Meanwhile, I went around Fossil Hill and up the ridge to the south of it. One of my 5x7s had clearly been taken from this ridge and I wanted to see if I could take a new photo from the same spot. After successfully accomplishing this, I retraced my steps along the ridge so that I could get a photo showing the relative locations of “The Gorge” and “The Tunnel” on Fossil Hill. After a noontime rain lasting almost two hours, I returned to the cabin locality to take more photos there. Kirk returned while I was doing that. He reported that he did not make it all the way to Buffalo Mountain because while I was getting rain down here, he was getting blinding snow up there. Knowing that Kirk is a hiking machine, I suggested that we walk over to a ridge about a half mile northeast of camp; I wanted to see about recreating a panorama that Merriam took from there. Kirk was game so off we went. I managed to locate the spot where the panorama was taken, however, the lighting was terrible. The sky was gray, the air hazy and there was no contrast whatsoever. Nevertheless, I took my photos and vowed to return the next morning when the light was bound to be better.

But on the morning of the 13th, we found snow on our tents and a good deal more dusting the hills around us. Not quite the hailstorm that Annie described in her scrapbook but I found it funny that we were encountering similar weather 112 years later. After packing up what stuff we could and leaving our tents to dry, we hiked back to that ridge north of camp to get the panorama. The clouds kindly parted for me and I was able to get some decent pictures.

In the next canyon to the north — North American Canyon, or what Annie referred to as the North Fork — we could see what remained of the abandoned Chinese mining camp that Annie had photographed. Kirk and I both wanted to explore that a bit, so after returning to camp, rolling up our tents, and packing the truck, we drove around the eastern foot of the ridge separating the canyons. The road here was extremely treacherous and eroded, but Kirk and his truck had no problem with it. We found the whole mining camp surrounded by barbed wire with “Danger” signs posted at regular intervals. This was wise, considering the many pits and tunnels riddling the area. We parked next to the fence, and armed with three of Annie’s photographs taken in the vicinity, we slipped under the fence. To be safe, we stuck to the dirt track that wound through the mounds of excavated earth and vertical mining shafts. I was able to get photos matching up with two of the prints, but to match up the third one, I had to climb up the ridge to the south, putting me almost back at the spot where I took the panorama of Fossil and Saurian Hills earlier. I then returned to the truck and Kirk drove us back out to Buena Vista Valley Road. We could now see that the higher peaks of the West Humboldts were covered with fresh snow; the East Range had gotten some and was still getting more as we drove north. We spent one last night in Winnemucca before returning to Berkeley.

I was incredibly pleased with the the results of the trip. First, it was a major bit of luck that we were able to contact the land owner and get permission to not only traverse his land but to camp there as well. Second, I felt confident that we had located six of the quarries that Annie and Merriam had photographed in 1905. Third, I was able to take new photographs close to the spots where Annie and Merriam had taken many of theirs. And lastly, I was able to put together this online story featuring the “then and now” photographs and had great fun doing it.

- Kelley, N.P., R. Motani, P. Embree, and M.J. Orchard. 2016. A new Lower Triassic ichthyopterygian assemblage from Fossil Hill, Nevada. PeerJ 4:e1626. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1626