Frankfurt, Germany is a museum town. Along the south side of the aptly named Main River are museums of Renaissance art, iconography, sculpture, design, and film. Each of the old waterfront mansions is home to treasures that spill out through their gardens and into the street, where today’s working artists sell pieces of equal beauty in the public market. It seems required that every footbridge across the river has a café and an accordion player at either end. North of the river is modern art, archeology, history, and at last the Naturmuseum Senckenberg, where I have the privilege of seeing one of the world’s largest collections of some ocean creatures whose odd lifestyles I’m interested in.

Over Earth’s history, the diversity of life cycle strategies that have evolved is phenomenal. Organisms’ life cycles vary with how they use resources in space and time. While life cycles can still change, lineages are somewhat constrained by wherever hundreds of millions of years of trying to maximize survival and reproduction in the moment has landed them today. Just think, modern day trees cannot quickly switch to bacteria-like short generation times to adapt to climate change. Life cycles are borne circumstantially out of many other traits, but they affect a lineage’s potential for generating new species – and their risk of going extinct.

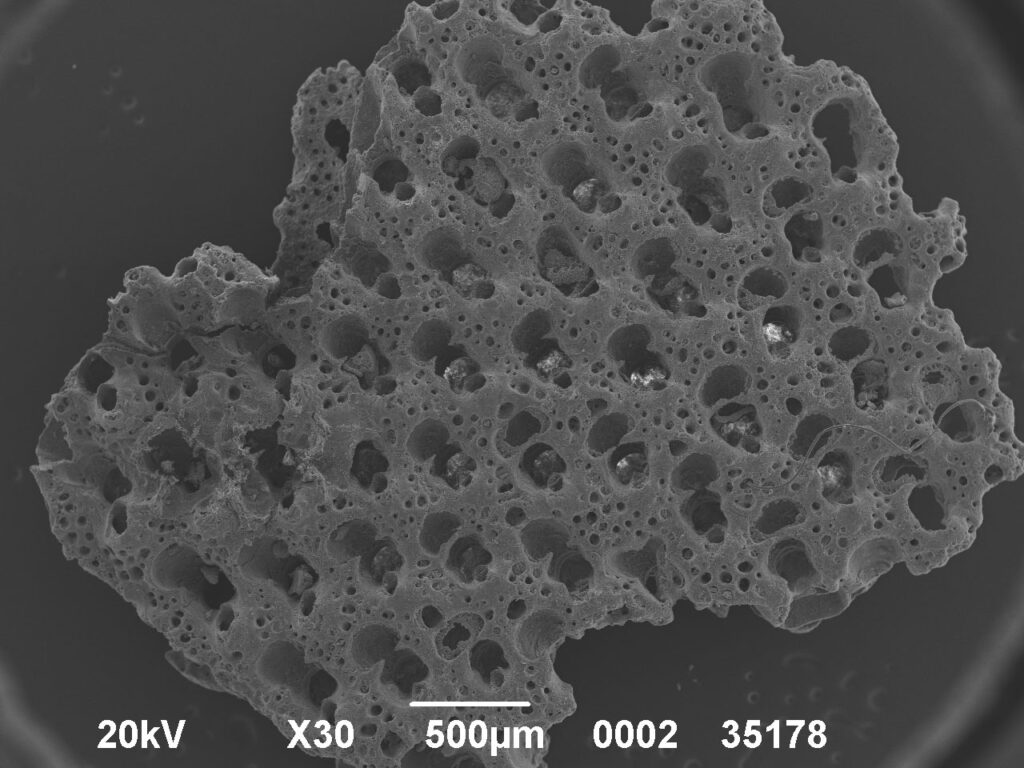

To understand which life cycles might be most vulnerable to habitat destruction and climate change, and how life cycles may shift in response, I look at long-term trends in the evolution of traits like reproductive mode and dispersal of offspring. Luckily, these traits are preserved throughout the history of life in the fossil record of marine animals like ostracods, foraminifera, and my favorite, the bryozoans.

Professor Ehrhard Voigt (1905-2004) collected at least 300,000 bryozoan specimens in his lifetime, which are preserved in his namesake collection at the Naturmuseum Senckenberg. The Voigt collection encompasses diverse taxa from much of geologic time and many geographic regions. I came to look at sediment samples still in Professor Voigt’s original packaging, which contain fossil bryozoans from the Cretaceous and Paleogene. Throughout the late Cretaceous, bryozoans were diversifying rapidly. Then the asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs also set bryozoans back. The bryozoans we see recovering afterwards in the Paleogene are somewhat different.

Thanks to the generous help of Dr. Joachim Scholz and his team, who curate the Voigt collection and utilize it for diverse applications, I obtained samples to begin one of my dissertation projects. I expect reproductive strategy will be quite variable within families, and I hope to identify distinct functional groups where certain reproductive strategies are affiliated with specific growth forms and paleoenvironments. Since the asteroid impact caused rapid environmental change, I expect which reproductive strategies predominate to change between the Cretaceous and Paleogene.

Today, when some bryozoans are becoming harmful invasive species and while the planet’s greatest bryozoan diversity is threatened by industrial fishing in New Zealand, understanding bryozoans’ life cycles is key to management. I’m grateful to the UCMP for funding my trip and to the Senckenberg for loaning me materials. In the future, I hope to revisit the localities from which Voigt collected these samples to get a better idea of their geologic context. This is the life cycle of research. Curation of museum collections is a vital part of the cycle new researchers can pick up where others left off, bringing new questions, technologies, and perspectives to phenomena that have been fascinating generations of observers.