Confinement at home due to the Covid-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity to reflect on the pace of my research over the last year. Thinking back to Aesop’s fable of the Tortoise and the Hare, I see that my research has adopted traits from both animals: sometimes moving slow and steady, while other times travelling at break-neck speed. Despite this variability in research pace, the UCMP has been a constant presence during my research through its supportive staff and generous financial assistance. Financial support from the UCMP, such as the Anthony Barnosky Honorary Fund for Graduate Student Support and from the Annie Alexander UC Museum of Paleontology Fellowship, has allowed me to travel to multiple museums to collect an incredible amount of data in a short amount of time, as well as the time to focus on research and my mentorship skills.

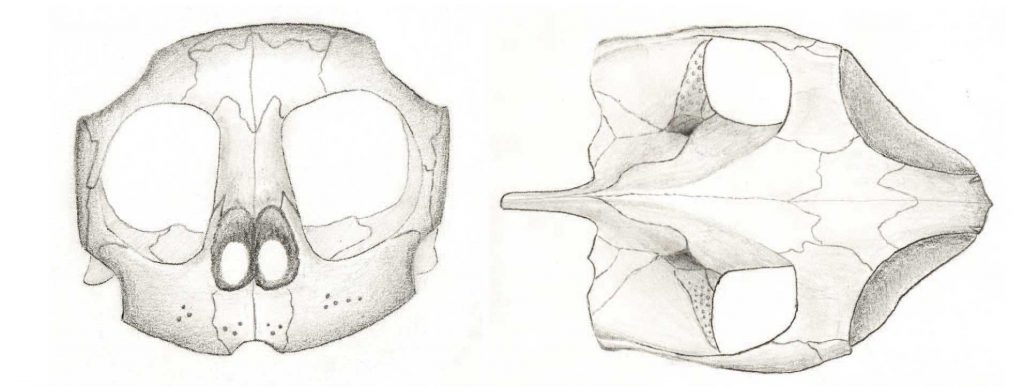

As a doctoral candidate within the UCMP and the Department of Integrative Biology, my research focuses on the morphology (i.e. shape) of skulls and the relationship of ecology to these shapes. Currently, I am collecting data on pond turtles (Family: Emdydidae) because they span a range of habitats, from terrestrial to semi-aquatic, consume a variety of foods, and their skulls show many differences in shape. This family of turtles also has a fossil record stretching back to the Eocene (42 to 56 Ma) allowing us to test hypotheses for how these turtles have changed over geologic time. To gather data on these turtle skulls, I employ CT-scanners similar to the ones seen in hospitals because we can capture high resolution images in modern specimens and digitally clear away fine sediment and rocks without harming the actual fossils. I use medical-grade technology to study fossils and turtle skulls to answer questions about how and why they have changed through time.

At the conclusion of the last academic year (May 2019), I traveled to Austin, Texas to participate in a short course hosted by the University of Texas High-Resolution X-ray Computed Tomography Facility (UTCT). There participants were introduced to the CT-scanning process and the available equipment at UTCT, as well as the software required to render CT-data into meaningful images for scientific interpretation. I had some prior experience with CT-scanning through the Berkeley Preclinical Imaging Facility (BPIF) but this workshop condensed so much into so little time, my head was spinning trying to contain all the information.

Seeing this Texas trip as an opportunity to collect data, as well as attend a workshop, I added 10 days to my stay and visited the Texas Vertebrate Paleontology Collections and the herpetology collections of the UT Austin Biodiversity Center. During this additional time, I collected observations on hundreds of modern, skeletonized turtles and fossil turtle specimens. And because I was participating in the CT-scanning workshop, I had some of these specimens scanned by the trained technicians at UTCT.

Shortly after my trip to Texas, I found myself on another plane to a part of the country well-known for its turtle diversity: Florida. Stretched across June and July, I spent four weeks visiting the Chelonian Research Institute (outside of Orlando) and the vertebrate paleontology and herpetology collections at the Florida Natural History Museum in Gainesville. Many people asked if I was thinking clearly by travelling to Florida during the summer and now know why they had asked. Anytime I went outside, if I wasn’t drenched from the downpour of a thunderstorm, the heat and humidity ensured that I was soaked with perspiration.

But, the wealth of turtles made the discomfort worth the effort. I found dozens of well-preserved fossil specimens and thousands of modern, skeletonized turtles for collecting observations. And again, I made use of local CT-scanning facilities to collect data. However this time, I was trained and permitted to operate the machine without assistance. Outside of the museum collections, I spotted many living turtles in ponds on the University of Florida campus and nearby Sweetwater Preserve, and I was quite happy letting these ones escape my research-gathering efforts. It was during this visit that I moved beyond turtles only as a study system and truly developed an affection for them.

After returning to the Bay Area for a couple weeks, it wasn’t long before I was travelling again on the next leg of my “research race”. My 2019 Summer culminated in a trip to Friday Harbor Labs, located on San Juan Island, north of Seattle. To reach the island, one either takes a ferry or a small plane.

At Friday Harbor Labs, I participated in a week-long workshop focused on the processing and analysis of three-dimensional data and after the trips to Texas and Florida, I had plenty of data (i.e. CT-scans) to work through. Every day of the workshop involved a couple lectures and several lab activities to test out new functions. The schedule was grueling at times but there was still time to meet other participants and discuss different applications of 3D-data. We also had time to take boats out on the water and look at wildlife in the evenings. Between the isolation on an island, the dedicated group of workshop leaders, and the activities to keep us busy, the trip to Friday Harbor felt akin to summer camp. And like summer camp, many of us were saddened when the week was over and we had to return to the “real world”.

After the whirlwind of travel last summer, I was eager to slow down and reestablish my roots in Berkeley and the UCMP. With data in hand, and more on the way in the form of borrowed specimens, I knew that I would need assistance preparing these skull scans for study. My advisor, Leslea Hlusko, and I determined that the University’s Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) was the way to find students to help with the next phases of my research. Over the last two semesters, I have had the pleasure of working with seven talented URAP students and training them in the research process. These students have learned to review scientific literature for ecological information, how to scan turtle skulls at the BPIF, and some students have explored scientific illustration to highlight specific anatomy in these skulls. This slow and steady research pace continued through the recent shelter-in-place orders with some slight modifications to our workflow. Because these students are away from Berkeley at their respective shelters, I have established a workstation at my home for them to access remotely where I can share the skills gathered over the summer to prepare CT-scans for analysis.

In the last few weeks of May 2020, the “hare’s pace” of research took over. With enough scans prepared, Team Turtle (as we have been dubbed by the Hlusko Lab) set the workstation to run analyses using geometric morphometric software and, after working nonstop for 36 hours, we had preliminary results! With the graphs and numbers produced by the workstation, I feverishly began to make sense of the data by looking for patterns that could represent changes in skull shape and ecology. I contacted Prof. Hlusko and other researchers to share these early thoughts and to confirm the patterns were real (which they all did). From there I began putting pen to paper and drafted an abstract, a brief synopsis of results, that I could submit to the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology for inclusion in their annual meeting later this year. In less than a week, we had completed scans, conducted analyses, dissected preliminary results, and submitted a conference abstract. It’s still early to share these preliminary results here but Team Turtle has more work planned for the upcoming summer and academic year and we look forward to sharing these results with the UCMP and scientific community as we become both Tortoise and Hare nearing the finish line and graduation!