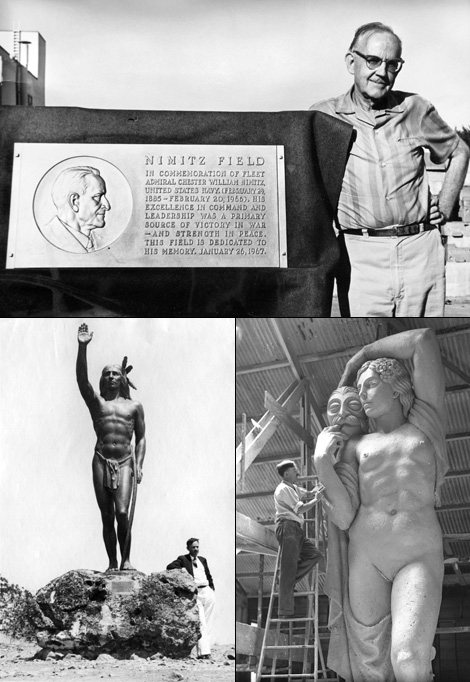

For the past three years or so I have been researching the life of sculptor William Gordon Huff. Never heard of him? That’s not too surprising since he didn’t have gallery shows and, to my knowledge, no major museum has examples of his work. But, if you do any traveling in California, there’s a good chance that you’ve seen Huff’s work without even knowing it, because most of his sculpture was public art, primarily in the form of bronze bas reliefs for historical plaques. Huff’s plaques can be found in Hangtown, Camptonville, Columbia, Ukiah, Peña Adobe Park, Angels Camp, Murphys, Napa, Monterey, Stockton, Pt. Reyes, Benicia, Alameda, and the University of California’s Angelo Reserve, to name a few places. And then there are his ceramic plaques on The Wall of Comparative Ovations in the Sierra foothills town of Murphys, but that’s a whole story in itself.

Huff’s most notable works, and those that garnered the most media attention, were created back in the 1930s, beginning with his 12-foot bronze statue of Chief Solano. This piece, dating from 1934, can still be seen in Fairfield in front of the Solano County offices at the corner of West Texas Street and Union Avenue.

But Huff is probably best known for his work on the 1939-1940 Golden Gate International Exposition (GGIE) that was held on Treasure Island. He constructed four, 20-foot-tall, free-standing figures — two of each — representing “The Arts,” “Industry,” “Science,” and “Agriculture” to fill eight archways in the octagonal Tower of the Sun, the central feature at the fair. He made 28 nine-foot-tall, free-standing female figures for buttresses surrounding the Court of Flowers, as well as two figures for the east side of the Arch of Triumph, which connected the Court of Flowers to the Court of Reflections.

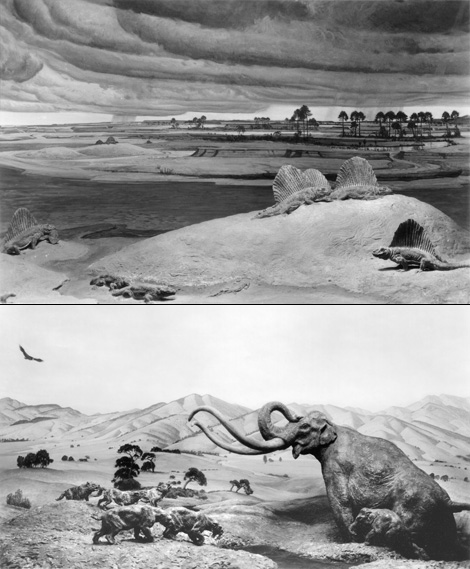

At the same time as he was working on these monumental sculptures, he was preparing GGIE exhibits for the Department of Paleontology. With painter Ray Strong doing the backgrounds, Huff sculpted the animals and foregrounds for six 1/6th-scale dioramas, depicting scenes from different geologic time periods. Huff also made five life-size heads of Miocene and Pleistocene mammals as well as a 13-by-7-foot bas relief of two American Lions (Felis atrox) attacking a giant Ice Age bison (Bison latifrons). Huff helped with three or four smaller exhibits in addition to these but no sculptures were needed for them.

The GGIE was intended to last only a single year, but because it didn’t make enough money, it ran for a second year. Huff made some new sculptural additions to the paleontology exhibit for 1940. He made 20 small plaques of prehistoric animals, a display of invertebrate fossils from Mt. Diablo, and perhaps more.

Since the GGIE exhibits were meant to be temporary, all of Huff’s sculptures were made of plaster. When I began my investigations into the life of William Gordon Huff, only two of his GGIE sculptures were known to still exist: (1) the large bas relief of the lions attacking the bison — this piece is in UCMP’s storage facility in Richmond — and (2) one of the five life-size heads, that of Synthetoceras (a Miocene deer-like mammal) that was restored and featured in UCMP’s Cal Day display two years ago. Nobody knew what had become of the six dioramas or the other four life-size heads; I assumed that they had fallen apart or had been destroyed. Who expected these temporary plaster sculptures to survive 75 years?

But in the span of one month, I have seen two of the six dioramas and two of the original five life-size heads — plus a completely unknown sixth head!

The dioramas

It took a while to track down the dioramas. Documents in the UCMP archives indicated that the six were brought back to Berkeley following the GGIE and were installed in Bacon Hall; they remained there through at least 1947. According to another archival document, the dioramas were transferred to the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco at some point. Two of the dioramas were acquired by San Francisco’s Randall Museum; when that was is unknown and what became of the other four is still a mystery. But in the early 1980s, the Randall Museum gave their two dioramas back to UCMP. They were kept at the museum’s Clark-Kerr storage facility until around 1997 when Diane Blades, representing the San Joaquin Valley Paleontology Foundation, took them south, ostensibly for the Fossil Discovery Center in Chowchilla. But they did not end up there. It’s not clear where the dioramas were between 1997 and 2012, the year they were discovered in a Madera Library storage space. Lori Pond, president of the San Joaquin Valley Paleontology Foundation, rescued the dioramas just days before they were scheduled to be broken up and hauled off to the landfill. Today, the two dioramas, representing the Permian and Pleistocene, are sitting in Lori’s garage. She hopes to find funding to have the dioramas cleaned and restored, but more importantly, she’d like to find them a new home; a place where the public can view them as it once did 75 years ago on Treasure Island.

The life-size heads

The discovery of two of the original GGIE life-size heads and of a third new one (perhaps a 1940 addition to the GGIE paleontology exhibit) was serendipitous. In 2012, Senior Museum Scientist Pat Holroyd was talking with Sally Shelton, Associate Director of the Museum of Geology and Paleontology Research Laboratory, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, about collections issues when Pat happened to mention Huff’s name. Sally revealed that in moving to a new building, their museum discovered three sculpted heads by Huff for which they’d love to find a new home. Pat relayed this information to Associate Director for Collections and Research Mark Goodwin. Mark, who has a strong interest in UCMP’s history, said that he would gladly take the heads and pay for the shipping costs. It took a while, but this summer, a 450-pound crate containing the three heads arrived at the museum. The two heads that were made for the 1939 GGIE are (1) Paramylodon, a giant ground sloth, based on a skull from the Pleistocene Rancho La Brea asphalt pits of southern California; and (2) Hipparion, a three-toed Miocene horse, from a skull found at the Black Hawk Ranch Quarry near Danville. The new head is of Pliohippus, a one-toed Miocene horse.

How did the heads end up in South Dakota? Both Professor Emeritus Bill Clemens and Sally Shelton believe that Reid Macdonald may have been responsible. Reid got his Ph.D. at Berkeley in 1949 and took a job as curator at the Museum of Geology, South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, that same year. But he left that position in 1957 and in the UCMP archives, there is a photo, circa 1957, that shows the heads still in Berkeley. Reid retired to Rapid City in 1980 and lived out the last 24 years of his life there. It’s still possible that he was behind the transfer of the heads to South Dakota but as yet, there is no hard evidence.

Nevertheless, now only the heads of Bison latifrons and Smilodon are unaccounted for. Since they are arguably the finest heads in the bunch, it’s entirely possible that they still exist somewhere. Perhaps someday, they too will return home to UCMP.