What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Africa? Probably a lot of big animals, right? Elephants and lions, zebras and cheetahs, hippos and rhinos, giraffes, and enormous herds of wildebeest moving across the savannah.

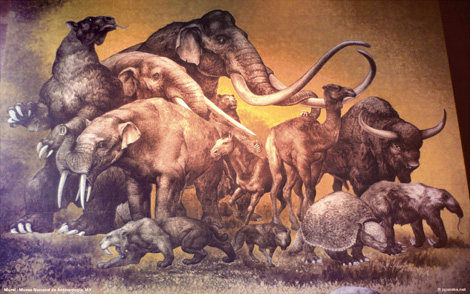

Well, what a lot of people don’t realize is that for most of the past 50 million years, most of the world looked a lot like Africa! Not that long ago, Europe, Asia, and North and South America all hosted relatives of elephants, zebras, and lions inhabiting ecosystems that looked a lot like today’s African savannah. There were rhinos roaming the Riviera, wooly mammoths wandering Wyoming, and Glyptodons (a kind of giant armadillo) gallivanting in Guyana. Here in California we had mammoths and mastodons (another elephant relative), horses and tapirs, oxen and antelopes, jaguars and lions, saber-toothed cats (our state fossil!), giant wolves, giant bears, giant bison, and (my favorite) giant sloths. South America had rodents the size of cows. Australia had wombats the size of hippos. Even relatively small islands had giant mammals, although not quite as giant as on the continents, because big animals tend to get smaller (and small animals bigger) on islands. There were giant lemurs on Madagascar, pygmy hippos in the Mediterranean, dwarf giant sloths in the Caribbean, and pygmy mammoths on California’s Channel Islands.

Scientists call these giant animals “megafauna” (mega = big, and fauna = animals). We still have megafauna in the world, but there used to be a whole lot more of it. In fact, it appears that having a large number of large-bodied animals in an ecosystem is actually the normal state for our planet, at least for the geologic era we are living in today, the Cenozoic (or “Age of Mammals”) . But sometime in the past 50,000 years (very recent geologically), everywhere except for Africa, most of those large animals became extinct. And we still aren’t sure why!

People often ask me, “Why was everything bigger in the past?” But I think the question should really be the other way around — “Why is everything so small now?” As a paleontologist studying the extinction of the megafauna, this is a question I ask on a daily basis.

Basically, there are two main ideas about why these large animals went extinct. One hypothesis is that the extinctions were actually due to us — to humans. The scientists who peg people as the culprits point to several lines of evidence: For one thing, in most of the places where the extinctions happened, large animals tend to disappear from ecosystems right about the same time that humans arrive for the first time (we know this from radioisotopic dating, scientific techniques that allow us to determine the exact age of fossils and the sediments they are found in). Also, in a few places, we actually have evidence of humans hunting extinct megafauna, such as mammoths. Finally, we know from modern situations that humans can have a major impact on animals, both directly (like hunting) and indirectly (like burning forests, fragmenting habitats, and causing erosion) .

The second hypothesis for why the megafauna went extinct is that the climate changed too much (or too fast), and the animals could not adapt to their new environments. We know that climate was changing at the time that the megafauna disappeared in many parts of the world, and in some places (including Ireland and northern Europe and Asia) the extinctions seem to be correlated with changes in vegetation and stress that can be directly linked to climate. Scientists who favor this hypothesis also point out that given all the fossils we have of extinct megafauna, only a handful show any evidence of hunting by humans.

Finally, there are some scientists — including myself and many of my colleagues — who think that most of the global megafauna extinctions probably resulted from a combination of both climate and human impacts. While there appear to be some places where extinctions may have been caused by climate change alone, and others where humans were the sole culprit, it seems that more species went extinct faster in regions where both of these factors came into play simultaneously. Whatever the answer, scientists all over the world are working to learn more about why our world looks so different today than it did in the past.

Why do we care about what caused the megafauna extinctions? Aside from the “wow” factor of reimagining these past ecosystems, large mammals constitute many of the world’s most currently endangered species, and so understanding how these animals are affected by climate changes and human activities might help us prevent the megafauna that are still alive today from disappearing too. This is important not only because it would be sad to have a world with no elephants, tigers, or polar bears, but also because losing these big animals could spell trouble for a lot of other species, including humans. Megafauna have major impacts on Earth’s ecosystems: they affect what plants grow where, how often and long forest fires burn, and how rich the soil is. They are important transporters of nutrients and seeds, and they can create and destroy habitat for smaller species. Megafauna are so important, in fact, that some scientists have proposed reintroducing them to habitats where they once lived — either by actually cloning extinct species, or by bringing in their closest living relatives from (where else?) Africa.

While these measures may help restore some natural areas, they are no substitute for maintaining healthy ecosystems in the first place. Hopefully, the research being done by scientists like me and my colleagues today can be used in conservation efforts, to help prevent the next big megafauna extinction.

• South American megafauna image from jqjacobs.net.