In July 2013, I visited the Denver, Colorado, area to collect data from two collections housed at United States Geological Survey (USGS) facilities and the University of Colorado (CU) Museum of Natural History. The USGS collections are housed in the Core Research Center on the Denver Federal Center campus. The building is also a repository for a large collection of soil samples and approximately 1.7 million feet of drilled rock, sediment, and ice cores. The Museum of Natural History is located at the University of Colorado campus in scenic Boulder, Colorado.

Though these collections cover a wide range of organisms from all over the world, my purpose there was to visit the fossil collections from the Western Interior Seaway. The Western Interior Seaway was a widespread shallow sea that flooded the North American continent from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean during the Late Cretaceous Period (about 100 to 65 million years ago). My work focuses on the faunal dynamics associated with invasion into these shallow sea environments. By more closely examining natural experiments in the past when biota encountered widespread novel physical conditions, we can better inform our predictions of how organisms will respond to the rapid global change happening today.

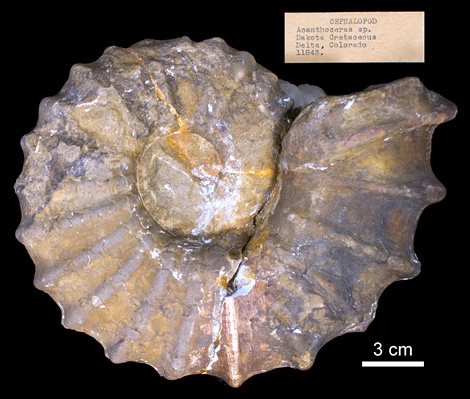

To that extent, I was interested in photographing and documenting a portion of the vast numbers of ammonites the two institutions have amassed over the years. Ammonites are a completely extinct group of hard-shelled cephalopods, related to the modern-day squid, octopus, and nautilus. Their fossils are often sold in rock shops because their beautiful undulating suture lines make them aesthetically pleasing items. They were incredibly diverse and abundant during the time the Western Interior Seaway existed, and so are an ideal study group to explore the dynamics of this system.

The large collection of Cretaceous bivalves, gastropods, and ammonites kept in the USGS collection is primarily the result of work done by USGS geologists, such as William Cobban, who collected and published on the Western Interior throughout the late 20th century and is still at the USGS facilities in Denver today. The collection contains drawer upon drawer of specimens. With the generous help of curator Kevin “Casey” McKinney, I photographed hundreds of ammonites, including many unpublished specimens. These photographs will be used to identify morphological features that may have influenced the degree to which ammonites were able to invade or adapt to the seaway. It was an adventure exploring the dusty cabinets, where every drawer held a surprise.

After four days in the suburbs of Denver, I took a bus up to beautiful Boulder, Colorado, just 45 minutes outside of Denver proper. After winding my way through the University of Colorado-Boulder campus, I arrived at the Bruce Curtis Building where the museum collections were housed. Collection manager Talia Karim greeted me and helped me get set up before showing me around the collections housed in the basement. Here, there were not as many specimens as at the USGS, but they were no less impressive. During the next three days, I photographed about a hundred more beautifully prepared specimens before I had to say goodbye to the Denver area.

The richness of the collections were such that, no matter how often I visit, there will always be much more to discover. I have plans to return in the near future to continue my explorations of these amazing and underused resources.