For a marine biologist, I spend a lot of time thinking about wood. What happens to it if it happens to wash into a stream? How much of it gets into the ocean? Where does it sink? What happens to it once it reaches the bottom? What animals are likely to make it their home?

I’m far from the first to think about the role of wood in ocean systems. In fact, Darwin thought quite a bit about how plant material might make its way into the ocean and how long different kinds of wood might stay afloat before sinking …

“It is well known what a difference there is in the buoyancy of green and seasoned timber; and it occurred to me that floods might wash down plants or branches, and that these might be dried on the banks, and then by a fresh rise in the stream be washed into the sea. Hence I was led to dry stems and branches of 94 plants with ripe fruit, and to place them on sea water. The majority sank quickly, but some which whilst green floated for a very short time, when dried floated much longer ….”

— Darwin, excerpted from On the Origin of Species, Chapter 11, 1859.

While Darwin’s focus was on wood as a rafting vehicle for dispersal, I am interested in the flip side: what happens to that wood once it sinks (where it is no longer useful for transporting land-dwelling animals)? Is the wood very useful to certain specialized denizens of the deep? Like Darwin, I recognized that there may be different effects depending on what kind of wood is involved, therefore, I set out to test whether the kind of wood matters in shaping the community of animals that colonize it.

About two and a half years ago, I had an opportunity to sink material from ten very different plants with support from Jim Barry and his lab at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). We took the research vessel Western Flyer to a site about a day’s steam from Moss Landing, CA, and with help from the remotely operated vehicle Doc Ricketts, we placed 28 wood bundles on the seafloor about two miles below the surface.

For two years I waited, not knowing whether I would ever see my beloved wood bundles again. But thanks to the expertise of my colleagues and good weather, I was able to retrieve every single wood bundle last October.

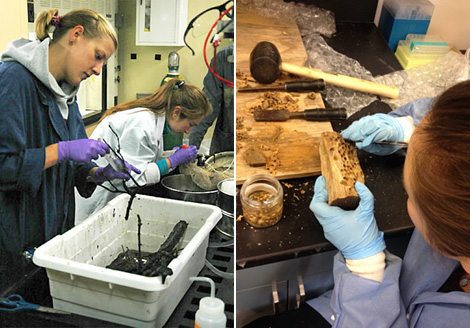

Since then, the lab has been quite the scene with six — yes, I said six — undergraduate research assistants busily extracting animals from the inside of logs and off the surface of leaves and needles. Each of them has developed an eye for detail that only hours upon hours of sorting tiny animals under the microscope can give you. Together we are sorting through heaps of critters and pulling out the patterns that make each colonist community different on each type of wood. Already patterns are emerging, but it will take more sorting, photographing and identifying organisms with help from taxonomist colleagues at other museums and institutions before we have the full story. Please stay tuned!

Learn more about this research in an interview that aired on the radio talk show The Graduates with Tesla Monson on KALX, April 22, 2014. You can download the audio podcast on iTunes.

Links to related articles and posts:

- Why land plants matter to deep-sea critters

- Making science out of chucking stuff into the sea

- The second world that forms on sunken trees