For the last semester I have been lucky enough to work as the GSR (graduate student researcher) for the spring semester at the UC Museum of Paleontology fossil preparation lab (prep lab) under the supervision of our new lab manager, Jason Carr.

It has been fun getting back into the preparation role, something that I did as a job after college. The material we have to work on varies a lot which keeps the work interesting. It requires a variety of techniques, so I get to do something different nearly every day.

When we started this project in the fall semester we stored dozens of boxes and stacked them high at the offsite Regatta storage facility. I have gone through enough material that now all of the boxes are in the prep lab. We are making good progress but there is so much we are still unpacking! But, it is okay because sometimes we find marvelous surprises like this nearly perfect marine snail shell (at left).

When we started this project in the fall semester we stored dozens of boxes and stacked them high at the offsite Regatta storage facility. I have gone through enough material that now all of the boxes are in the prep lab. We are making good progress but there is so much we are still unpacking! But, it is okay because sometimes we find marvelous surprises like this nearly perfect marine snail shell (at left).

We are constantly amazed at the number of different materials that the collectors used to wrap and protect the fossils. One shark tooth was even cleverly protected in a cut-up Coke bottle! I guess you use whatever you can in the field. The majority of the fossils that I am preparing are fish bones and scales — several of the formations that the Caldecott Tunnel plunges through were marine, such as the Sobrante Formation where most of our material was found. We are also finding a variety of plants, charcoal, bones of mammals from both the ocean and the land (including tiny mammal teeth, which will be the subject of a later blog), turtles, whole oyster beds, and whole rock samples that we process for marine microfossils and shells of foraminifera. These are important fossils because they allow us to address questions of climate and stratigraphy and GSR Susan Tremblay will tell you more about the preparation of those materials in her blog.

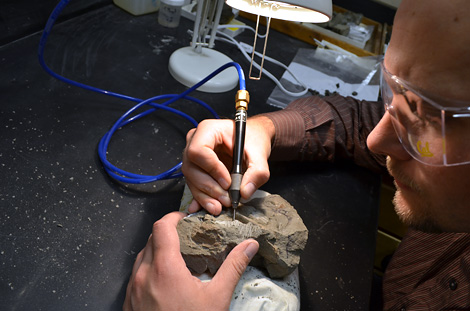

I am using some quite different techniques than Susan since most of the fossils that I am preparing are visible with the naked eye. Most of what I am doing is surprisingly low tech! It does take a lot of practice though and a good supply of patience. Some fossils are solid enough that we can use special air-powered tools like this pneumatic air scribe.

Most of the marine mammal fossils are strong enough for this. The tools vibrate the rock though so more delicate fossils need to be stabilized with resins. I usually apply these with an eyedropper or gently brush them on like you can see here.

These techniques are simple but really important if the fossils are to last in the collections until someone wants to come examine them.

I am excited to spend this time working in the lab. I love opening a new box and getting to see firsthand some of the remains of the animals that roamed over the East Bay hills. To learn about a world that existed so long ago and was so different that it had camels and rhinos living in it and then to realize that it existed right here in the East Bay? Exhilarating! Hard to picture perhaps but every fossil we unwrap brings us a little closer to visualizing that world.

Read other blog posts about the Caldecott Tunnel fossils:

— Fossil neighbors, posted September 12, 2012

— The arrival of the fossils, posted October 1, 2012

Photos courtesy of Ashley Poust and Jason Carr