Solving the mysteries of the past and present one rock at a time

East of the Berkeley campus, we see the beautiful, green Berkeley Hills, the golden letter “C” and a somewhat classy-looking, dome-shaped building on the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory campus. This houses the ALS, or Advanced Light Source. Personally, I find the name a bit silly because it doesn’t seem to capture the awesomeness of this giant machine. It’s like calling the Space Shuttle a Progressive Flying Tool.

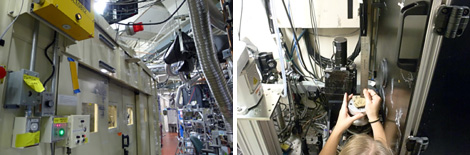

The ALS is a synchrotron, a particular type of particle accelerator. The particles are sped up by a shifting magnetic field within a closed circuit. The shape of this circuit is an almost circular polygon and since the building was specifically designed for the synchrotron, the building is round. But what happens inside?

Each time when the particle beam is bent at each of the polygon’s corners, light is produced — primarily ultraviolet and x-rays. The x-rays are not your ordinary dental office x-rays, but much “harder” x-rays. Unlike the relatively harmless photo at the tooth doctor, this beam would kill you before you could say “¿qué?”

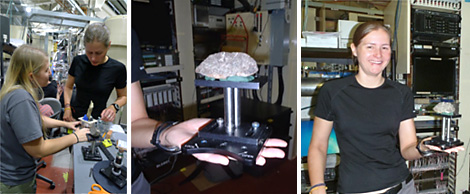

But what can paleontologists and paleobotanists do with this advanced light? Hard x-rays allow us to see fossils while they are still inside the rock. This means that you don’t have to crack open the rocks, clear away rock matrix and run the risk of damaging precious fossils. In some cases, the material is simply too fragile to be prepared; it would not hold up. Scanning the rock allows us to make 3D reconstructions of fossils hidden inside the rock without damaging them.

We’ve been scanning all kinds of really old fossils: horsetails from the Carboniferous (~300 million years ago, or Ma), kelp holdfasts from the Oligocene (~30 Ma), tiny (3 mm or ~1/8 inch) and not so tiny (7 cm or ~2¾ inch) pine cones, early land plants from the Devonian (~390 Ma), and pollen cones of extinct redwoods from the Cretaceous (~70 Ma). The size of the fossils is limited by the size of the protective shielding enclosure that keeps the scientists safe while using these lethal x-rays.

Because the cyclotron basically runs 24/7, the scanning time slots are generally 24 hours long and scanning rocks can take a while. Here’s the general process that we go through for each scan: