Another in a series of blog posts relating to the museum’s “cataloging the archives” project

Ask children what their favorite dinosaurs are, and it’s almost guaranteed that Triceratops (refer to them by their nickname, Trikes, and you’ll earn tons of street cred) will be on the list. The three-horned, frilled wonder is one of the most recognizable creatures of the Cretaceous. Many a visitor has walked by the Triceratops display here in the Valley Life Sciences Building’s Marian Koshland Bioscience and Natural Resources Library. Over time, the display has grown, not only to include more skulls, but to tell a bigger story. Now there are three skulls in the display, each with its own interesting history, but when taken together the tale reaches almost epic status (okay, “impressive” status).

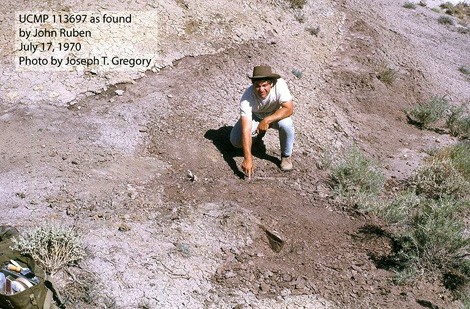

The largest of the skulls is UCMP specimen 113697, also known as “Ruben’s Trike.” While on a UCMP field expedition to Montana and neighboring states in July, 1970, paleontology graduate student John Ruben (now a professor in the Department of Zoology, Oregon State University) discovered the skull in the roughly 68-million-year-old rocks of the Hell Creek Formation of eastern Montana. The Hell Creek is one of the most fruitful formations for Trike discoveries, and if you’ve done field work in the Upper Cretaceous of Montana and haven’t come across some part of a Triceratops, you’re doing something wrong.

The medium-sized Triceratops skull, UCMP 136306, is also known as the “McGuire Creek Trike” since its discovery in badlands of the Hell Creek Formation exposed in the vicinity of this creek drainage in McCone County, Montana. Weathered fragments of bone or “float” from the skull were first sighted by paleontology undergraduate Wayne Thomas in the summer of 1984 on a UCMP field research trip. Further excavation by UCMP Assistant Director Mark Goodwin and crew that summer confirmed Wayne’s discovery was a nearly complete juvenile Triceratops skull. The find was exciting in itself, but it also helped fill in some holes in the understanding of Triceratops growth from baby to adult (known as ontogeny) and generated new research by Goodwin, his colleague Jack Horner from the Museum of the Rockies, and their students. For more information on Trike ontogeny, stay tuned for a future blog entry centered on this exact topic.

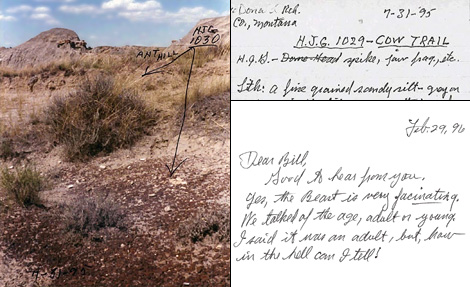

The smallest of the Trike skulls, UCMP 154452, was found in the Hell Creek Formation (see a trend?) of Montana by long-time UCMP field associate and collector, Harley J. Garbani, in 1995.

When Harley came across the specimen, he first identified it as a possible pachycephalosaur because the tiny brow horn so closely resembled the horns and knobs seen ornamenting the back of the skulls of pachycephalosaurs, or “dome-headed” dinosaurs. Being a very young individual, likely less than a year old, the skull showed features not seen before on a Trike, was very delicate, and in many pieces. Trying to determine what some specimens are from many fragments can be a tedious and insanity-inducing ordeal (ask any fossil preparator).

After corresponding with, and providing pictures to, Mark Goodwin and Professor Bill Clemens, the specimen was correctly identified and also keyed Goodwin into finding a near identical isolated postorbital or “brow” horn from the skull of another baby Triceratops in the UCMP collections.

Harley’s discovery was a game-changer since it was, and still is, the smallest Triceratops skull and by inference, the youngest yet known. Together, these three skulls tell a story about skull development and growth in a dinosaur that was named by O.C. Marsh of the Yale Peabody Museum over 120 years ago!

UCMP paleontologists are still discovering new things about this very popular dinosaur. Fossils are often known for whatever novel thing they can tell us, but sometimes a seemingly small and, at first, very fragmentary fossil becomes significant when studied in the context of other fossils and when you hear the story behind its discovery. These Triceratops skulls are interesting on both counts!