DAY 1 (5/17/2011): I work with Professor Roy Caldwell to study the evolution of the behaviors and morphology of mantis shrimps – pugnacious crustaceans that are distant cousins to lobsters, true shrimps, and crabs. Mantis shrimps use fearsome raptorial appendages to smash or spear their prey. Even more surprisingly, some mantis shrimps live in male-female pairs in sandy burrows, with both sexes caring for the young and sharing food. Social monogamy, when a single male and female live as a pair for an extended period of time, is very rare among crustaceans, so I’m naturally interested in how it arose.

In particular, I’m really curious to find out whether lifestyle traits, such as living in sandy burrows or ambush hunting, may have opened the door for the evolution of social monogamy. To try to answer my questions, I will be looking at some of the thousands of mantis shrimp specimens housed at the Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Museum Support Center. By looking at the morphologies and behaviors of different mantis shrimp species and considering their evolutionary histories, I hope to figure out whether the evolution of morphological traits like the relative size and shape of eyes, raptorial appendages, and body shape, is correlated with the evolution of social monogamy, ambush hunting, and burrow-living.

I’ll be updating this blog while I am in Washington D.C. with more about my research and lots of tasty tidbits about mantis shrimp biology. So stay tuned!

———————————————————————————————————————————

DAY 2 (5/19/2011): My first day in Washington D.C. started off with a 6am wakeup call, followed by a rushed morning of picking up a rental car at Dulles International Airport, driving to the nearest metro station to take a train into Washington D.C., and literally running to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History to make my 9:30am appointment to obtain a visitors badge. Then, before I could even catch my breath, I was on the Smithsonian Employee shuttle and off to the Museum Support Center (MSC) in Maryland.

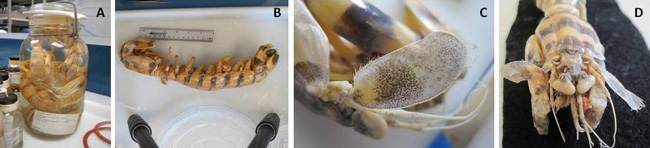

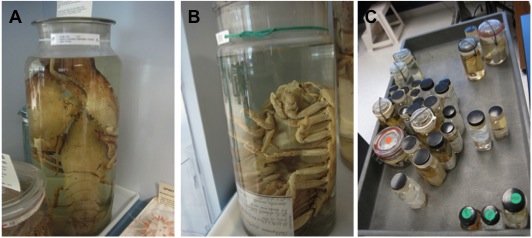

The MSC houses all of the invertebrate collections that are stored in ethanol, as well as many of the Invertebrate Zoology research labs. Museum Specialist Karen Reed met me at the entrance of the building. Karen led me through the labyrinth of hallways in the MSC, set me up at a work bench with all the tools I needed, and oriented me to the Crustacean collections, helping me select some specimens to get started on. The Crustacean collections take up two large rooms in the MSC. Walking through shelves containing thousands of specimens, I was continuously distracted by amazing creatures – giant American lobsters, spiny lobsters, giant isopods, and king crabs, all stored in jars of slightly yellowed ethanol. This place is great!

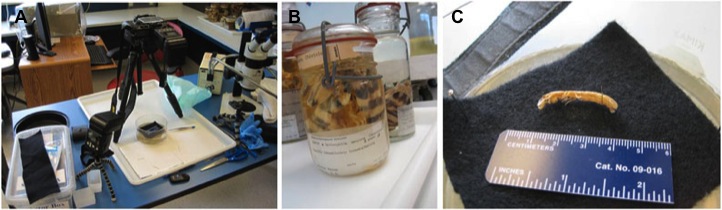

By the time I collected my specimens, it was time to eat lunch. The entire Invertebrate Zoology staff eats together everyday, which is great for visiting scientists like me because it gives us a chance to get to know everyone. After lunch, I set up my camera and started taking pictures. In half a day, I got through most of the Nannosquilla (a genus of small mantis shrimps) and started up on the Lysiosquillina (a genus of HUGE mantis shrimps), taking more than 100 pictures of animals ranging from 10mm to 30cm!

After a long, but fruitful, day at the MSC, I finally got to head to the apartment that my husband and I are renting for the next week and a half. It felt great to collapse on the couch and put my feet up. After a quick nap, my husband and I went out for a quick dinner – of course, I had to order the crab cake and shrimp dish because there’s nothing quite like eating the animals you study!

———————————————————————————————————————————

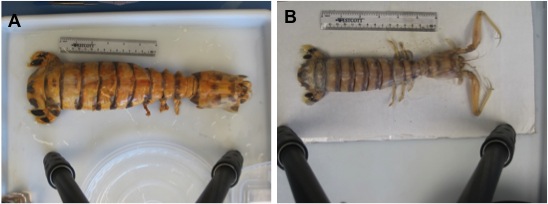

Giant mantis shrimps and other members of the Lysiosquillina genus have fascinating behaviors. They are socially monogamous. Heterosexual pairs dig long, U-shaped burrows in the sand. Males in this genus usually do the hunting, waiting at the opening of the burrow for a fish to swim by then grabbing it from the water column with their long, sharp raptorial appendages. Then they share the food they catch with their mate. We have been observing one male Lysiosquillina maculata in our lab in Berkeley for many years. He always provisions his mate first, coming back a few minutes later for more fish.

Lysiosquillina maculata is also sexually dimorphic – that is, males and females have slightly different body shapes. Males have larger eyes and longer raptorial appendages. We suspect that this might be because they spend more time at the burrow opening, catching food and defending themselves and their mates.

———————————————————————————————————————————

DAY 4 (5/23/2011): Starting my first full week at the Smithsonian this morning, I was excited to take a look at some other socially monogamous mantis shrimps in the Lysiosqulloidea clade.

After waking myself up with a big cup of coffee, I proceeded up to the large crustacean storage room in Pod 5 of the Museum Support Center with Museum Specialist Karen Reed . I was curious to see Pod 5 for more than just it’s scientific significance because it was prominently featured as the site of the protagonist’s lab in Dan Brown’s novel The Lost Symbol. Unlike its description in the novel, it is filled with jar after jar of specimens preserved in ethanol. Karen helped me navigate through the collections, returning the specimens that I looked at last week and choosing new specimens to examine. Everything is organized with an accession number, much like in a library, otherwise if a specimen were misplaced, it might not be found again for decades or even centuries!

I pulled more than 40 specimens to examine over the next few days from several families of mantis shrimps in the Lysiosquilloidea clade – the Nannosquillidae, the Coronididae, and the Tetrasquillidae. I’m particularly interested in looking at the Nannosquillidae family because it contains both promiscuous and socially monogamous species. I hope that by looking at morphological traits that occur in socially monogamous species but not in promiscuous species, I can better understand howsocial monogamy evolved.

———————————————————————————————————————————

DAY 5 (5/25/2011): Today is a rather special day for me – my birthday! And what better way to spend it than at the MSC, looking at mantis shrimps?

In the past two days, I’ve photographed and measured 48 mantis shrimps – not bad, considering it takes me about 20 minutes to process each specimen! First I look up the accession number in the Smithsonian’s online database, which provides information on when and where it was collected, as well as any notes from collection and later curation. After adding this information to an excel spreadsheet, I use calipers to measure the mantis shrimp’s eyes, antennal scales, legs, and total length. I then mount the specimen in a dissection dish with pins, getting it in just the right position to photograph. I take several shots of each animal from different view points to make sure that I am getting all of the morphological information I need, remounting it each time. I always include a small ruler in the photo so that I have an idea of the size of the animal.

This morning, I searched the wet collections for some of the rarer genera of Lysiosquilloidea. Once I measure and photograph the 13 specimens that I pulled this morning, I will have completed my survey of the Lysiosquilloidea. Of course, I couldn’t look at every lysiosquilloid mantis shrimp in the Smithsonian collection – the museum has over 400 mantis shrimps just in this super-family – but I did manage to examine at least a few examples of each genus!

Tonight my husband and I are going to celebrate both my birthday and my success thus far in the Smithsonian collections with a delicious Italian dinner!