The Gastropoda

Snails and slugs, limpets, and sea hares

|

No. of described species: 62,000 |

Partula taeniata, a tree snail from Moorea, French Polynesia. |

Gastropods have figured prominently in paleobiological and biological studies, and have served as study organisms in numerous evolutionary, biomechanical, ecological, physiological, and behavioral investigations.

They are extremely diverse in size, body and shell morphology, and habits and occupy the widest range of ecological niches of all molluscs, being the only group to have invaded the land.

Fossil record

[Need content]

Life history & ecology

Gastropods live in every conceivable habitat on Earth. They occupy all marine habitats ranging from the deepest ocean basins to the supralittoral, as well as freshwater habitats, and other inland aquatic habitats including salt lakes. They are also the only terrestrial molluscs, being found in virtually all habitats ranging from high mountains to deserts and rainforest, and from the tropics to high latitudes.

Gastropod feeding habits are extremely varied, although most species make use of a radula in some aspect of their feeding behavior. They include grazers, browsers, suspension feeders, scavengers, detritivores, and carnivores. Carnivory in some taxa may simply involve grazing on colonial animals, while others engage in hunting their prey. Some gastropod carnivores drill holes in their shelled prey, this method of entry having been acquired independently in several groups, as is also the case with carnivory itself. Some gastropods feed suctorially and have lost the radula.

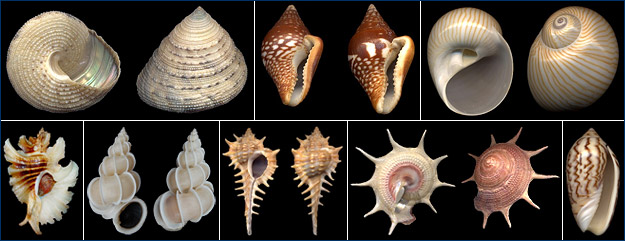

Variation in shell morphology in some marine gastropods: Clockwise from top left, Calliostoma antonii from off the Pacific coast of Panama; the dovesnail Columbella strombiformis from offshore near San Carlos, Mexico; the moonsnail Natica elenae from the Gulf of Panama; Oliva peruviana from shallow water near Iquique, Chile; the turbinid Guildfordia triumphans from Wakayama, Japan; the muricid Vokesimurex elenensis from the Pacific coast of Mexico; a wentletrap, Epitonium scalare, from the Phillippines; and another muricid, Pteropurpura trialata, from offshore near Los Angeles, California. |

Most aquatic gastropods are benthic and mainly epifaunal but some are planktonic. A few such as the violet snails (Janthinidae) and the sea lizards (Glaucus) drift on the surface of the ocean where they feed on floating siphonophores, while others (heteropods and Gymnosomata) are active predators swimming in the plankton. Some snails (such as the whelk Syrinx aruanus) reach about 600 mm in length. There is also a very large (and poorly known) fauna of microgastropods that live in marine, freshwater and terrestrial environments. It is amongst these tiny snails (0.5-4 mm) where many of the undescribed species lie.

Most gastropods have separate sexes but some groups (mainly the Heterobranchia) are hermaphroditic. Most hermaphroditic forms do not normally engage in self-fertilization. Basal gastropods release their gametes into the water column where they undergo development; derived gastropods use a penis to copulate or exchange spermatophores and produce eggs surrounded by protective capsules or jelly (see Busycon spiratus photo below).

The first gastropod larval stage is typically a trochophore that transforms into a veliger and then settles and undergoes metamorphosis to form a juvenile snail. While many marine species undergo larval development, there are also numerous marine taxa that have direct development, this mode being the norm in freshwater and terrestrial taxa. Brooding of developing embryos is widely distributed throughout the gastropods, as are sporadic occurrences of hermaphrodism in the non-heterobranch taxa.

The basal groups have non-feeding larvae while veligers of many neritopsines, caenogastropods, and heterobranchs are planktotrophic. Egg size is reflected in the initial size of the juvenile shell or protoconch and this feature has been useful in distinguishing feeding and non-feeding taxa in both Recent and fossil taxa.

More on morphology

Gastropods are characterized by the possession of a single (often coiled) shell, although this is lost in some slug groups, and a body that has undergone torsion so that the pallial cavity faces forwards. They have a well-developed head bearing a pair of cephalic tentacles and eyes that are primitively situated near the outer bases of the tentacles. In some taxa the eyes are located on short to long eye stalks. The mantle edge in some taxa is extended anteriorly to form an inhalant siphon and this is sometimes associated with an elongation of the shell opening (aperture) — this is shown in the photo of the caenogastropod Conus bullatus below. The foot is usually rather large and is typically used for crawling. It can be modified for burrowing, leaping (as in conchs, Strombidae), swimming, or clamping (as in limpets). The foot typically bears an operculum that seals the shell opening (aperture) when the head-foot is retracted into the shell (see photos below). While this structure is present in all gastropod veliger larvae, it is absent in the embryos of some direct developing taxa and in the juveniles and adults of many heterobranchs. The nervous and circulatory systems are well developed with the concentration of nerve ganglia being a common evolutionary theme.

The shell is typically coiled, usually dextrally, the axis of coiling being around a central columella to which a large retractor muscle is attached. The uppermost part of the shell is formed from the larval shell (the protoconch). The shell is partly or entirely lost in the juveniles or adults of some groups, with total loss occurring in several groups of land slugs and sea slugs (nudibranchs).

From left, a whelk, Busycon spiratus, almost entirely out of its shell — the yellowish disc is the operculum; another Busycon spiratus individual, entirely withdrawn inside its shell, with the operculum sealing off the aperture; egg capsules being deposited on the sand by Busycon spiratus; a larval harp shell, Morum oniscus, begins building its shell (protoconch). |

Externally, gastropods appear to be bilaterally symmetrical. However, they are one of the most successful clades of asymmetric organisms known. The ancestral state of this group is clearly bilateral symmetry (e.g., chitons, cephalopods, bivalves), but gastropod molluscs twist their organ systems into figure-eights, differentially develop or lose organs on either side of their midline, and generate shells that coil to the right or left. The best documented source of gastropod asymmetry is the developmental process known as torsion.

Systematics

There is still controversy about the phylogenetic position of some gastropod clades. Though the clades discussed below are well supported in many modern analyses, their relationships to each other remain somewhat unclear.

The neritopsines Nerita fulgurans (left) and Nerita versicolor (right). |

Neritopsina

Neritopsina contains several families which have marine, freshwater, and terrestrial members. The largest family, Neritidae, includes many marine, brackish, and freshwater lineages. This family alone has probably invaded freshwater habitats at least six times (Holthuis 1995). The two terrestrial families, Helicinidae and Hydrocenidae, can be found as far back as the Devonian.

Neritopsines come in all shapes and sizes and can have coiled to limpet-shaped shells, with one species (Titiscania) being a slug. This group was previously included within the "Archaeogastropoda." The shell is never nacreous and an operculum is present in adults. The radula has many teeth in each row.

Vetigastropoda

The Vetigastropoda is a diverse group that includes the keyhole and slit-limpets (Fissurellidae), abalones (Haliotiidae), slit shells (Pleurotomariidae), the top shells (trochids), and about 10 other families.

All are marine, and have coiled to limpet-shaped shells. This group was also previously included within the "Archaeogastropoda." The shell is nacreous in many of these taxa and an operculum is usually present. The radula has many teeth in each row.

Assorted vetigastropods: from left, abalone; Puncturella longifissa, a keyhole limpet — note the hole or "keyhole" just above the apex of the shell through which water is expelled; Margarites marginatus, a trochid; and the radula of the vetigastropod snail Sinezona rimuloides, greatly magnified. |

Caenogastropoda

Caenogastropoda is a very large, diverse group containing about 100 mostly marine families. Familiar groups include the littorines (Littorinidae), cowries (Cypraeidae), creepers (Cerithiidae, Batellariidae, and Potamididae), worm snails (Vermetidae), moon snails (Naticidae), frog shells (Ranellidae and Bursidae), apple snails (Ampullariidae) and a large, almost entirely marine group of about 20 families that are all carnivores belonging to the clade Neogastropoda. These neogastropods include whelks (Buccinidae), muricids (Muricidae), volutes (Volutidae), harps (Harpidae), cones (Conidae), and augers (Terebridae). Caenogastropod shells are typically coiled, a few being limpet-like (e.g., the slipper limpets, Calyptraeidae). One family (Vermetidae) has shells resembling worm-tubes. While most caenogastropods possess a shell that encloses the animal, it is reduced in some and has become a small internal remnant in the slug-like Lamellariidae. Eulimidae are all parasitic on echinoderms, most being shelled ectoparasites but some have become shell-less, worm-like internal parasites. Some groups have invaded freshwater, the most important being the Viviparidae, Ampullariidae, Thiaridae (and several closely related families), and smaller-sized snails belong to the very diverse families Hydrobiidae, Bithyniidae, and Pomatiopsidae. There are a few terrestrial taxa, the cyclophorids being the most significant family.

Caenogastropods were previously comprised of the "Mesogastropoda" and "Neogastropoda" within the "Prosobranchia." Of these two groups only the Neogastropoda remains as a monophyletic group. The shell is never nacreous and an operculum is present in adults. Apart from members of the Neogastropoda, the radula usually has only seven teeth in each row. The radula of neogastropods has five to one tooth in each row and is absent in some species.

Heterobranchia

Heterobranchia is a very large group that has only recently been recognized as a clade within Gastropoda. Several marine and one freshwater group (Valvatidae) that were previously included in the "Mesogastropoda" and two very large groups previously given subclass status, the Opisthobranchia and Pulmonata (collectively the Euthyneura), were found to be related lineages in a recent phylogenetic analysis. The more basal members comprise about a dozen families that are mostly small-sized, poorly-known operculate groups.

The opisthobranchs comprise about 25 families and 2000 species of the bubble shells (many families) and the sea slugs (many families) as well as the sea hares (Aplysiidae). Virtually all opisthobranchs are marine with the majority showing shell reduction or shell loss and only some of the "primitive" shell-bearing taxa having an operculum as adults.

The pulmonates comprise the majority of land snails and slugs, a very diverse group comprising many families and about 20,000 species. A few marine pulmonates (including the limpet-shaped Siphonariidae) comprise groups that mostly inhabit estuaries. A basal group of mainly estuarine air breathing slugs (Onchidiidae) also has terrestrial relatives (Veronicellidae, Rathouisiidae). Some important groups of freshwater snails are also included here — the Lymnaeidae, Planorbidae, Physidae and Ancylidae. The operculum is absent in all pulmonates except the estuarine Amphibolidae and the freshwater Glacidorbidae. The shells of heterobranchs are never nacreous.

Assorted heterobranchs: clockwise from top left, the bubble shell Hydatina physis from the Canary Islands; the Clown Nudibranch, Triopha catalinae, from off the Santa Barbara coast; the Ragged Sea Hare, Bursatella leachii, from off the Florida coast; the siphonariid Physella heterostropha from northeastern Florida; Euglandina rosea, a carnivorous terrestrial spiraxid pulmonate from Florida; the Florida Leatherleaf, Leidyula floridana, a veronicellid from Florida, about 8 cm long; and the pond snail Lymnaea stagnalis. |

Patellogastropoda

The File Limpet, Lottia limulata (left), and a group of Colisella (Lottia?) sp. limpets, from the intertidal off California. |

All are marine and limpet-shaped and many live in the intertidal zone. This group was previously included within the "Archaeogastropoda." The shell is nacreous in some taxa and the operculum is absent in adults. Their radula has several teeth in each row, some of which are strengthened by the incorporation of metallic ions such as iron.

Cocculinidae

Cocculinids are a group of simple white limpets that occur on waterlogged wood and other organic substrates in the deep sea.

The relationships of Cocculinidae are unclear. Several recent phylogenetic analyses place them as closely related to the Neritopsina, or as the sister group to the clade that includes Caenogastropoda and Neritopsina. Some authors believe, however, that they are members of the Neritopsina. Further systematic research is needed to clarify the relationships of this enigmatic group.

Literature cited

Original text by Paul Bunje, UCMP. Partula taeniata by Carole Hickman, UCMP; Abalone and Colisella (Lottia?) sp. by Sherry Ballard, © 1999 California Academy of Sciences; Sinezona rimuloides radula © 2004 Dr. Daniel L. Geiger; ; Triopha catalinae © 2002 Larry Jon Friesen; Lottia limulata by E. Eugenia Patten, © California Academy of Sciences. All other photos courtesy of www.jaxshells.org, with Pteropurpura trialata by Roger Clark, Nerita fulgurans by Marlo Krisberg, and Bursatella leachii by Joel Wooster.