This post’s text is also available in Spanish.

Congratulations to graduate student Emily Lindsey, this year’s recipient of the George D. Louderback Award! Emily has been hard at work the past few years investigating the timing, dynamics, and key players behind the late Pleistocene extinction of megafauna in South America.

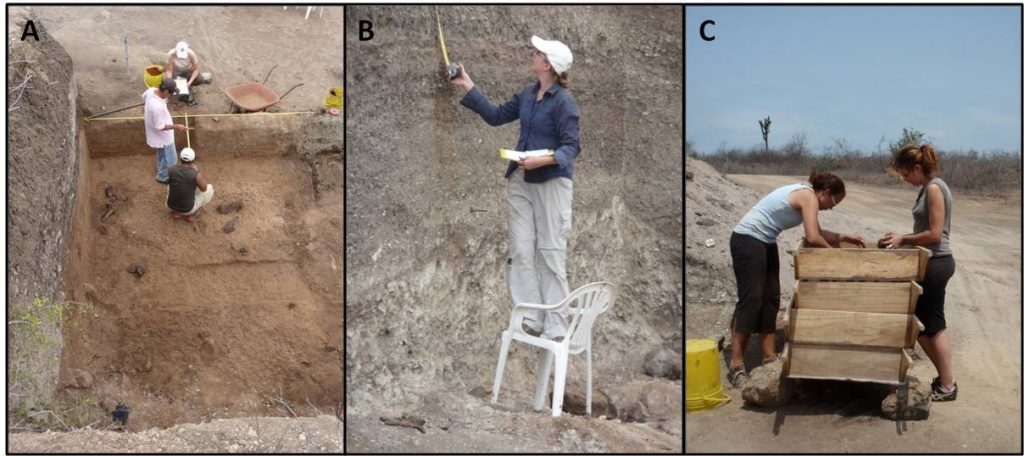

Like the famous La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, California, Emily’s excavation site on the Santa Elena Peninsula in Ecuador is an asphalt seep preserving the remains of a wide array of organisms. However, unlike the Tar Pits in California, the Ecuador site doesn’t appear to be a tableau depicting the tragic demise of animals stuck in tar. Instead, it is likely the final resting place of remains transported by running water and then covered by nearby asphalt.

So what mysterious late Pleistocene megafauna did she uncover in the seep? Mainly giant ground sloths (Eremotherium laurillardi) ranging from juveniles to adults, along with gomphotheres (elephant-like relatives of mastodons), giant armadillos and prehistoric horse. In general, Emily’s site had rather reduced biodiversity compared to other notable tar seeps. In fact only herbivores were found, unlike La Brea, which included the infamous and carnivorous sabertoothed cat and dire wolf.

Emily couldn’t do all this work without some help. For the excavation, she brought together a slew of collaborators from across continents to uncover (zing!) and understand the mysteries surrounding the late Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions. The Universidad Estatal Peninsula de Santa Elena (UPSE) sponsored the excavation and kept the fossil finds at the Museo Paleontologico Megaterio (MPM). Members of the Page Museum in California also flew down to Ecuador, bringing their expertise on the La Brea Tar Pits and asphalt seeps. And, several U.C. Berkeley students and alumni have volunteered their time on the dig. Several international articles were written about Emily’s exciting work, including one from the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles and the Universidad Nacional de Piura (UNP).

Emily’s collaboration with UNP members in Peru was part of her goal to compare asphalt seeps from different locales. “I think the Talara tar seeps in Peru are pretty similar to La Brea, geologically & taxonomically, just my site in Ecuador is distinct from them,” says Emily. “This isn’t necessarily true of other asphalt sites here on the Santa Elena Peninsula, which may represent more traditional “tar pit” scenarios.” Emily presented her results in a lecture at UNP last year.

Another large focus of Emily’s work has been to tease apart the roles of climate change and habitat degradation from the arrival of humans on the disappearance of large mammals. Several of the fossils uncovered at her site in Ecuador were found with cut marks. Though this might suggest that humans played a hand in overharvesting and subsequently pushing these mammals to extinction, there is no further evidence of human activity at her site. “It is also possible that the marks are ‘taphonomic’ features, caused when the bones were swept down a river or rubbed against other bones and rocks in the tar pit,” says Emily. Likely both climate change and human activities led to the downfall of these South American megafauna. The question is, how much did each factor contribute.

With a much deserved award under her belt, we look forward to hearing more about Emily’s discoveries in the future!

Felicitaciones a la estudiante de doctorado Emily Lindsey, ganadora este año del Premio George D. Lauderback. Emily ha estado trabajando los últimos años investigando la cronología, los patrones y los actores principales en la extinción de la megafauna sudamericana al fin del Pleistoceno.

Tal como el famoso sitio Rancho La Brea en Los Ángeles, California, USA, el sitio que Emily está excavando en la Península de Santa Elena en Ecuador es un charco de asfalto que preserva los restos de una gran variedad de organismos. Sin embargo, a diferencia de los charcos de brea en Los Ángeles, el sitio en Ecuador no parece que fue una trampa donde varios animales murieron atrapados en brea, sino la ultima morada de restos trasladados por agua corriente y luego enterrados en el asfalto.

¿Y cual megafauna misteriosa ha encontrado Emily en los charcos de Santa Elena? Principalmente perezosos gigantes (Eremotherium laurillardi), desde críos hasta adultos, junto con gonfoterios (un pariente de los mastodontes parecidos a elefantes), armadillos gigantes, y caballos prehistóricos. En total, el sitio tiene menos biodiversidad en comparación con otros conocidos fosilíferos charcos de brea. De hecho, hasta ahora solo han encontrado herbívoros, a diferencia de Rancho La Brea, donde los fósiles más encontrados incluyen los famosos – y carnívoros – tigres dientes de sable y Canis dirus.

¡Emily no podría hacer todo este trabajo sin ayuda! Para las excavaciones, unió a un grupo de colaboradores de distintos continentes a des-cubrir (:)) y entender los misterios sobre la extinción de la megafauna Pleistocena sudamericana. La Universidad Estatal Península de Santa Elena (UPSE) apoyó la excavación y guardó los fósiles excavados en el Museo Paleontológico Megaterio (MPM). Personal del Museo de Historia Natural en Los Ángeles, California, también vino a ayudar con las excavaciones, contribuyendo con su alta experiencia y conocimiento sobre los charcos de brea. Además, varios alumnos y exalumnos de la Universidad de California en Berkeley han llegado como voluntarios a ayudar con los excavaciones. Algunos artículos internacionales han sido escritos sobre el trabajo emocionante de Emily, incluyendo uno del Museo de Historia Natural en Los Ángeles, y otro del Universidad Nacional de Piura (UNP) en Perú.

La colaboración de Emily con el personal del UNP fue en conexión con su proyecto de comparar charcos de brea de distintos lugares. “Yo creo que los charcos de brea en Talara, Peru son bien parecidos, geológicamente y taxonómicamente, con los de Rancho La Brea en Los Ángeles; solo el sitio que yo tengo es distinto,” dijo Emily. “Esto no necesariamente es el caso con los otros sitios de asfalto que encontramos aquí en la Península de Santa Elena, los cuales podrían representar escenarios mas tradicionales de “trampas de brea.”

Otro gran enfoque del trabajo de Emily ha sido diferenciar las contribuciones de cambios climáticos y degradación de hábitats y la llegada de los primeros humanos a Sudamérica, como causantes de la desaparición de mamíferos gigantes del continente. Algunos de los fósiles descubiertos en su sitio en Ecuador fueron encontrados con marcas parecidos a las hechas con cuchillos. Aunque esto podría sugerir que los humanos tenían un papel en la sobrecaza de estos animales y su eventual extinción, no hay mas evidencia de acciones humanos en el sitio. “También es posible que las marcas sean características ‘tafonómicas,’ producidas cuando los huesos fueron arrastrado por un río o cuando se frotaban unos contra otros o contra piedras en el charco de brea,” dice Emily. Probablemente, ambos procesos – cambios climáticos y acciones de humanos – contribuyeron a la extinción de la megafauna Sudamericana. La pregunta es, ¿cuánto contribuyó cada factor?

Ya con un premio bien merecido, ¡esperaremos escuchar mas sobre los descubrimientos de Emily en el futuro!