About UCMP : News and events : UCMP newsletter

Tiktaalik comes to UCMP

by Brian Swartz

|

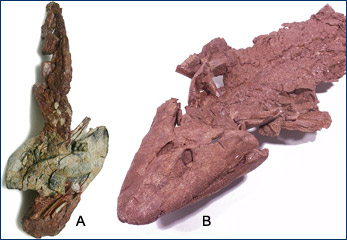

Click on Figures 1–3 to see enlargements. Figure 1. The original discovery of Tiktaalik roseae in 2004. This specimen is preserved upside down, with the distal tip of the lower jaws (see arrow) exposed from the overlying rock. Bottom left is anterior.

|

It was the summer of 2004 and Ted Daeschler (Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia), Neil Shubin (University of Chicago), Farish Jenkins (Harvard University), and colleagues were collecting fossils on Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. They had been conducting fieldwork in this area since 1999, sampling early–Late Devonian age (~375 Ma) rocks for the earliest relatives of terrestrial vertebrates. With much troubleshooting and minimal luck from 1999 to 2003 — and approximating $100,000 per field season — they were told that this summer would be their final fully funded expedition. However, that year, while working their NV2K17 site (discovered by Jason Downs in 2000, then an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania), Steve Gatesy (Brown University) noticed the tip of a flat, pointy "snout" peering out of a section that he was clearing (see photo on page 5). Considering the age and paleoenvironmental signature of these rocks, the discovery of a flat-headed bony animal was very big news. In the fickle cold and rainy weather, the 2004 field crew encased this specimen and several others in plaster jackets, soon loaded them onto helicopters, and awaited the subsequent discovery by preparators of what exactly lay entombed in these 375-million-year-old rocks. Over the next several months, preparators working at the Academy of Natural Sciences and at the University of Chicago soon unearthed the animal, Tiktaalik roseae, which lay buried beneath a mound of growing debris (Fig. 2). The finding of Tiktaalik was eventually published in 2006 (Daeschler et al. 2006, Shubin et al. 2006), about two years after its original discovery.

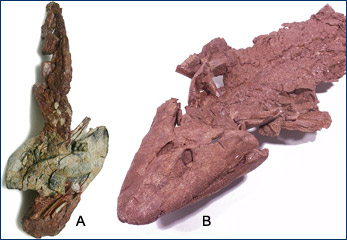

Since publication, T. roseae has gained worldwide attention for its importance in vertebrate evolution and for the story associated with the adventures of its field crew. Considering its popularity, there have been numerous requests by museums and researchers for casts of Tiktaalik. Recently, UCMP acquired casts of both an articulated pectoral (front) limb and of the holotype specimen (what the "snout" in Figure 1 was just the tip of) discovered that summer of 2004 (Fig. 3). The UC Museum of Paleontology is quite privileged to be one of the few museums in the world to house material of this unique animal.

Figure 2. Preparation series of the holotype specimen from Figure 1. Prepared by Fred Mullison at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Bottom is anterior. |

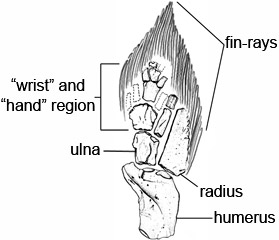

In addition to its contribution to museum collections, Tiktaalik will also be used in our Evolution of the Vertebrates lab course offered through the Department of Integrative Biology. The importance of Tiktaalik in vertebrate evolution is illustrated by several interesting features and will reinforce the hands-on education Berkeley students obtain from our specimen-based museum and laboratory courses. For example, the pectoral limb of Tiktaalik contains a humerus, radius, ulna, and fin-rays (bones that support the fin-webbing) as in many other sarcopterygians ("fleshy-limbed" or "lobe-finned" vertebrates). However, unlike many sarcopterygians, it also has an interesting array of "wrist" and "hand" bones situated between the fin-ray and forearm regions (Fig. 4). Considering that Tiktaalik has this combination of general (i.e., ancestral) and specific (i.e., derived) characteristics—through comparison with other lobe-finned specimens—it might be easy for students to identify these elements and reconstruct what the pectoral limb of Tiktaalik might look like. Alternatively, because the holotype specimen (Fig. 3B) illustrates some limb elements better than the isolated pectoral limb specimen (Fig. 3A) (and vice versa), when students try to reconstruct the forelimb of Tiktaalik (say, as a lab exercise), they will gain that kind of experience particular to paleontology — through observation, comparative anatomy, and interpretation — that Daeschler, Shubin, and Jenkins originally got when they described this incredibly interesting animal. Progressing beyond the simple pedagogical level of "what is it, what is its name, when did it live, etc.," the utility of comparative material and hands-on learning lies at the heart of UCMP's role in education and outreach at UC Berkeley and beyond. We are thrilled that Tiktaalik can contribute to this objective, and to those who helped bring this material to UCMP, all we can say is, "thank you."

|

|

|

|

Figure 3. Photos of two original Tiktaalik specimens. A. Dorsolateral view of the right pectoral limb of NUFV 108. Bottom is proximal. B. The holotype specimen NUFV 110 fully prepared. Bottom left is anterior. Figure 4. Reconstruction of the right pectoral limb of T. roseae in ventral view. Proximal is toward the bottom of the page. |

For more information:

Daeschler, E.B., N.H. Shubin, and F.A. Jenkins, Jr. 2006. A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan. Nature 440:757–763.

Shubin, N.H., E.B. Daeschler, and F.A. Jenkins, Jr. 2006. The pectoral fin of Tiktaalik roseae and the origin of the tetrapod limb. Nature 440:764–771.